Complete study: Unconventional Natural Gas Development and Hospitalization for Heart Failure in Pennsylvania by Tara P. McAlexander , Karen Bandeen-Roche , Jessie P. Buckley , Jonathan Pollak , Erin D. Michos , John William McEvoy , and Brian S. Schwartz, J Am Coll Cardiol, 2020 Dec, 76 (24) 2862–2874

Central Illustration

Abstract

Background

Growing literature linking unconventional natural gas development (UNGD) to adverse health has implicated air pollution and stress pathways. Persons with heart failure (HF) are susceptible to these stressors.

Objectives

This study sought to evaluate associations between UNGD activity and hospitalization among HF patients, stratified by both ejection fraction (EF) status (reduced [HFrEF], preserved [HFpEF], not classifiable) and HF severity.

Methods

We evaluated the odds of hospitalization among patients with HF seen at Geisinger from 2008 to 2015 using electronic health records. We assigned metrics of UNGD activity by phase (pad preparation, drilling, stimulation, and production) 30 days before hospitalization or a frequency-matched control selection date. We assigned phenotype status using a validated algorithm.

Results

We identified 9,054 patients with HF with 5,839 hospitalizations (mean age 71.1 ± 12.7 years; 47.7% female). Comparing 4th to 1st quartiles, adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence interval) for hospitalization were 1.70 (1.35 to 2.13), 0.97 (0.75 to 1.27), 1.80 (1.35 to 2.40), and 1.62 (1.07 to 2.45) for pad preparation, drilling, stimulation, and production metrics, respectively. We did not find effect modification by HFrEF or HFpEF status. Associations of most UNGD metrics with hospitalization were stronger among those with more severe HF at baseline.

Conclusions

Three of 4 phases of UNGD activity were associated with hospitalization for HF in a large sample of patients with HF in an area of active UNGD, with similar findings by HFrEF versus HFpEF status. Older patients with HF seem particularly vulnerable to adverse health impacts from UNGD activity.

***

Unconventional Natural Gas Development and Heart Failure: Accumulating Epidemiological Evidence Editorial Comment by Barrak Alahmad and Haitham Khraishah, J Am Coll Cardiol, 2020 Dec, 76 (24) 2875–2877

Introduction

… Various stressors are implicated in the different stages of UNGD; these include:

1) environmental exposures including, but not limited to, particulate and gaseous air pollutants and water quality (1–3);

2) psychosocial exposures such as stress from noise and traffic (4); and

3) contextual exposures such as social disruption and community livability (5) (Figure 1).

The rapid UNGD booming around the world and in the United States was outpacing environmental health studies on affected local communities. Although the initial reports of adverse health impacts of UNGD mainly examined perinatal outcomes and respiratory effects (1), more emerging studies are now examining a variety of health outcomes, including cardiovascular diseases.

Download Figure

Download PowerPoint

Heterogeneity of Stressors From Unconventional Natural Gas DevelopmentPotential stressors and exposures involved in unconventional natural gas development that could lead to adverse cardiovascular impacts on affected communities. NOx = nitrogen oxides; SOx = sulfur oxides.

Around the world, heart failure is a global health crisis affecting at least 26 million people (6). Heart failure is also expensive to treat. Despite advances in medical management, heart failure is characterized by recurrent hospitalizations that are inevitable (7). In the United States, more than $31 billion were spent on heart failure in 2012, and the expected cost in the future could increase by 127% by 2030 (8).

In this issue of the Journal, McAlexander et al. (9) used electronic health records to obtain data consisting of >9,000 heart failure patients who could be at risk of UNGD exposure across Pennsylvania. To the best of our knowledge, this comprehensive case-control analysis is the first epidemiological investigation regarding the impacts of UNGD on heart failure outcomes. The exposure metric, which captures not only distance to wells but also the number of wells, their depth, and stages of production, has been used in previous papers, most notably by Casey et al. (10). The novelty here is the study population; that is, the thousands of heart failure patients living in nearby communities affected by UNGD, which enabled McAlexander et al. (9) to investigate heart failure exacerbation leading to hospitalization. The authors found that heart failure patients who were exposed to the highest quartile of UNGD activity were more likely to be hospitalized for heart failure compared with those who were in the lowest quartile of the exposure. The group described a biological gradient that patients with severe heart failure (higher Charlson index of morbidity) were more susceptible to the UNGD activity metric. Many of the postulations on the possible mechanistic pathways come from our understanding of air pollution effects on cardiovascular diseases, which include systemic inflammation, autonomic dysfunction, prothrombotic pathways, and epigenomic changes (11).

In the early 2010s, the scientific community was calling for “good” epidemiological studies to evaluate the health effects of fracking (12,13). In the current observational study, McAlexander et al. (9) applied extensive and rigorous methods involving both the design and the statistical approach. First, the study used negative exposure controls. This is a precautionary tool to assess sources of spurious causal inference (14). In brief, the authors assigned future exposure to outcomes that happened in the past. This temporal mismatch should not yield meaningful or adverse effects, and if it did, then there could be an unmeasured spatial confounder that is accounting for the observed relationship. Second, the authors conducted a number of sensitivity analyses, including restricting age groups, alternative measures of patients’ duration of care, and different functional forms of the exposure metric. Third, they controlled for a wide range of covariates. Their results were consistent and robust across all these measures. Most importantly, the effect size is probably too large to be explained away by an unmeasured confounder. To illustrate this, one can calculate the E-value, which is the minimum strength of association that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both the exposure and the outcome, conditional on the measured covariates, to fully explain away a specific exposure–outcome association (15). If we apply this on the reported odds ratio comparing the fourth quartile of the UNGD activity metric versus the lowest quartile in the pad preparation phase (odds ratio: 1.70; 95% confidence interval: 1.35 to 2.13; model 5), we will then need to think of some unmeasured confounder that has a relative risk association of at least as large as 1.93 (1.60 for the confidence interval) with both UNGD pad preparation and heart failure hospitalization to explain away the observed association. If anything, the observed results are likely attenuated toward the null due to possible nondifferential misclassification bias in the case ascertainment and exposure assessment.

As the epidemiological evidence starts to accumulate, there are many challenges yet to be addressed that preclude our full understanding of the potential health effects from UNGD on nearby local communities. First, exposure assessment needs to be advanced toward understanding the specific mechanisms in which UNGD can affect health outcomes. For example, a recent study showed that particle radioactivity (particulate matter that transports high-energy alpha-emitting radionuclides from the external environment to human tissues through inhalation) is a potential exposure pathway of UNGD (16). Moving forward, we need to better understand the mediating effects by air and water pollutants, as well as particle radioactivity, and the existence of racial disparities in the fracking impacts. We also need a better understanding of the effects of various environmental exposures on cardiovascular health. Fine-tuning of cause-specific cardiovascular morbidity and mortality along with translational studies are needed to further characterize the pathophysiological pathways.

***

Study: PA heart failure patients near fracking were more likely to be hospitalized, 12,000 patients analyzed over 8-year period by Reid Frazier, December 21, 2020, State Impact

Heart failure patients who live near fracking operations were more likely to be hospitalized than those who live farther away, according to a new study.

Researchers at Drexel and Johns Hopkins studied medical records of 12,000 heart patients in Pennsylvania between 2008 and 2015.

The authors reported “significantly increased odds of hospitalization among heart failure subjects in relation to increasing” fracking activity in the area near them. Heart failure includes any condition, like a heart attack, that leads to the inability of the heart to pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs.

Older patients and those with more severe heart failure “seem particularly vulnerable to adverse health impacts” from nearby fracking, the authors stated.

The study appeared in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. The study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), part of the National Institutes of Health.

The study’s lead author, Tara McAlexander, a post-doctoral research fellow in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel University, said that increased noise, air pollution, and traffic from fracking could all explain the higher levels of heart patient hospitalizations found in their study.

“We thought about all those potential exposures and how they might impact heart failure. And pretty much all of them really suggested that they would be exacerbated if you were exposed (to fracking) and you were in that vulnerable state of having heart failure in the first place.”

The authors reported they did not have data on the diet or lifestyle of the study’s subjects, but doubted whether the higher hospitalization rates they observed in heart patients living near fracked gas wells could be chalked up to those factors.

Joan Casey, assistant professor in environmental health sciences at Columbia University, said in an email the study “adds to mounting evidence that fracking is related to adverse health outcomes.”

Casey, who worked with some of the paper’s co-authors when she was a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, but was not involved in the study, said it suffered from the same limitations “of essentially all epidemiologic studies of fracking to date: we don’t know what component of fracking is responsible. Is it air pollution? Water pollution? Noise pollution? Psychosocial stress? Something else?”

Casey also pointed out the study ends in 2015 “and so may not reflect current fracking exposures in Pennsylvania.”

Zach Rhinehart, assistant professor of cardiology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, said there have been calls for “high quality evidence” about fracking and health impacts for years.

He said the study’s statistical model was strong enough to essentially rule out any other causes besides fracking for the increased hospitalizations the authors found.

Fracking “really does seem to be associated with hospitalization for heart failure,” said Rhinehart, who was not involved in the study. “And it doesn’t seem like any other(factors) are explaining that away.”

Rhinehart said that because fracking plays a big role in the state’s economy and energy portfolio, “it would be really important to know what about it is causing the problem.”

“You can’t dismiss the fact that the natural gas development is a major economic driver and it’s something that’s very important to many people’s livelihoods,” Rhinehart said. “So it’s really important to find out why is this association there?”

McAlexander said the study fits with a growing list that shows increased health problems for people who live near fracking. Those problems include increased incidence of asthma, heart problems, and mental health issues, as well as health problems related to pregnancy, like birth defects, pre-term birth and low birthweight.

“These activities — unconventional natural gas development and fracking specifically — are having negative impacts on the health of populations living nearby.”

She says because of this, she thinks fracking should be banned.

“We know enough to know that we shouldn’t be doing this and that it’s negatively impacting populations,” McAlexander said.

Another co-author, Brian Schwartz, professor in the Department of Environmental Health Sciences in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, has publicly come out against fracking.

McAlexander acknowledged that burning natural gas instead of coal has resulted in widespread air quality gains in the U.S., but said “the way the natural gas industry produces natural gas in this country, it shifts a lot of those health burdens to nearby populations.”

Nate Wardle, a spokesman for the Pennsylvania Department of Health said the agency is reviewing the study. The agency is funding a pair of studies to look at the relationship between fracking and health outcomes like cancer, asthma and poor birth outcomes.

“It is the department’s goal through these studies to better understand both long term impacts and short term, acute impacts,” Wardle said, in an email.

A spokesman for the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, asked to comment on the study, said only that the agency would be “reviewing the (Department of Health) study,” which is slated to be completed in December 2022, and that the agency “will consider” the study and others like it when it revisits its oil and gas regulations in the future.

A June 2020 Pennsylvania grand jury report slammed both the DEP and the health department for failing to protect the public from the health effects of fracking.

Fracking industry groups say they are “safely and responsibly” developing the state’s natural gas resources while meeting the state’s requirements for the industry.

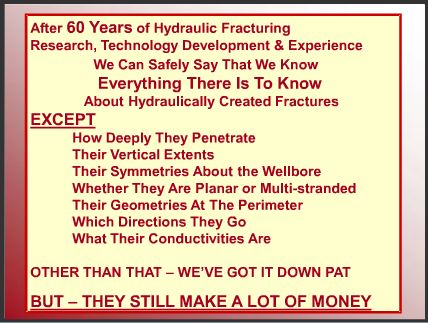

“Our industry is grounded in advanced scientific research, and protecting the health and safety of communities where we live and operate is our highest priority,” Marcellus Shale Coalition President Dave Spigelmyer said, in a statement. ![]() Where’s the proof the industry is “grounded” in advanced scientific research? CEOs publicly admit companies do not know what they are doing, that frac’ing is a “brute force and ignorant” experiment.

Where’s the proof the industry is “grounded” in advanced scientific research? CEOs publicly admit companies do not know what they are doing, that frac’ing is a “brute force and ignorant” experiment.

And we are now finding out, a decade later, some frac’ers only made “a lot of money” because they scammed banks and investors! Now that investors have caught on, money is fast drying up, with frac’ers bankrupting themselves all over the carpet-bombed place.

Companies, regulators, politicians and too many courts only want the frac-harmed gagged and don’t give a shit about health and safety – in Canada, Australia, the USA and everywhere else where industry is frac’ing. Lobby groups like CAPP and Marcellus Shale Coalition further harm us, our loved ones and communities, with their incessant lying and propagandizing.![]()

Rhinehart, of the University of Pittsburgh, said any negative health outcomes from fracking should be balanced against whatever positive factors the industry brings to those it benefits — like workers or landowners who have leased property for gas drilling.

“Maybe now they can afford their blood pressure medicines or their cholesterol medicine or smoking cessation aides,” ![]() Like a rapist, the patronizing prof insults and blames the harmed. As vile as AER’s outside counsel, Glenn Solomon, admitting that law-violating frac’ers gag the harmed so that companies can “do it again down the street.”

Like a rapist, the patronizing prof insults and blames the harmed. As vile as AER’s outside counsel, Glenn Solomon, admitting that law-violating frac’ers gag the harmed so that companies can “do it again down the street.”![]() Rhinehart said. “It could be…that the economic benefits from this allow more people to live better lives and to be happier and healthier despite the negative effects of the pollution.”

Rhinehart said. “It could be…that the economic benefits from this allow more people to live better lives and to be happier and healthier despite the negative effects of the pollution.”![]() What amount of money makes being poisoned to the point of being hospitalized and or killed OK? One million dollars, a billion? Many that signed leases in North America were conned just like investors were and are paid not one penny for their troubles and the endless harms, even with signed contracts! Worse, too many companies refuse to pay their taxes and refuse to clean up after they rape out profits, dumping ongoing harms, leaks, pollution, clean up on the harmed and taxpayers.

What amount of money makes being poisoned to the point of being hospitalized and or killed OK? One million dollars, a billion? Many that signed leases in North America were conned just like investors were and are paid not one penny for their troubles and the endless harms, even with signed contracts! Worse, too many companies refuse to pay their taxes and refuse to clean up after they rape out profits, dumping ongoing harms, leaks, pollution, clean up on the harmed and taxpayers.![]()

Refer also to:

Yup, frac’ing is an experiment alright, a brute force, ignorant, extremely harmful one:

2006 12: When I discovered my community’s drinking water aquifers were deliberately illegally frac’d by Encana/Ovintiv with 18 Million liters of frac fluid and undisclosed additives, and years of lies by Encana/Ovintiv, regulators and politicians, all hope in me died.

2010:

2013 02 19: FOIP letter from AER (previously ERCB) on all fracks gone bad in Alberta. Imagine the results if this FOIP were done today!

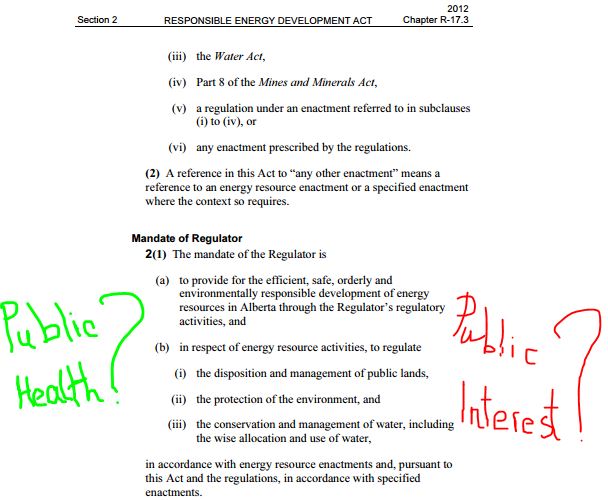

2013: Alberta gov’t brings in REDA (a ridiculously dishonest name), changing the regulator to AER (apparently in response to Ernst’s lawsuit), removes public interest from its mandate

It can get pretty testy. Encana fracked somebody else’s well – in yet another case of “involuntary stimulation”

Fracking the Hawkwoods near Calgary, dead cows and…RADIATION?

2014: New Mexico wells have had over 100 frack hits, many caused by Encana

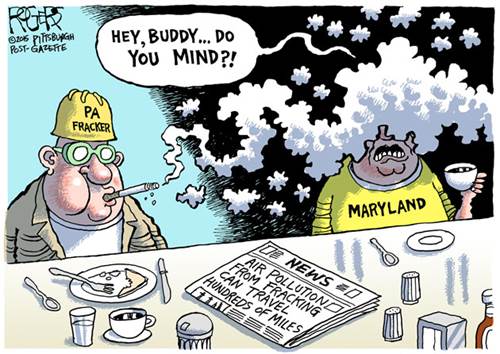

2015: Fracing’s long reach: Fracking Wells Could Pollute The Air Hundreds Of Miles Away

2015 05 20: Total Misleads Danish Authorities by Promising Full Fracking Control

2016 12 20: The only safe fracking regulation is a ban

2017: Nasty! Supreme Court of Canada pisses on the rule of law, damages Canada’s Charter and knowingly lies in their ruling in Ernst vs AER. Worse, the court sends the lie to the media but not the part of their ruling where the lie is specified as such.

2019 07 03: Overview of International Human Rights Court Recommending Worldwide Frac Ban

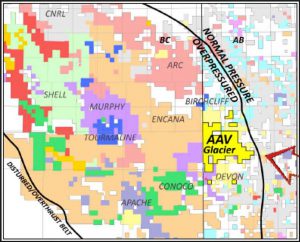

2019 07 06: Encana’s Supersize Spatial Intensity Frac Cube Experiment Fails

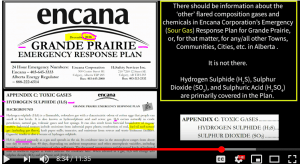

Updated Nov 12, 2019: Shortly after Will Koop posted his clip (above), Encana removed its Grand Prairie Emergency Response Plan (ERP) from the Internet. It’s vital that such important documents relating to public health and safety are accesible, so it has beenuploaded here (takes time to load).

The UK Government and its advisers “marginalised, downplayed or ignored” public health concerns about shale gas exploration and fracking in England, new research has concluded.

A study by the University of Stirling found that science was frequently ignored and the shale gas industry was very effective in influencing decision-making.

This had been to the detriment of public health, with vulnerable and disadvantaged communities at the greatest risk, it said.

Frac’ers are never satisfied; they always demand more wells, more facilities, more deregulation, more billions in subsidies and freebies as they lose more billions for investors and cause more harm upon harm.

Hellish infrastructure and expansion as far as the eye can see.

“What regulation or law fixes this?” (Hint: None, other than criminalizing frac’ing.)

2020: As of the date of this post, still no federal or provincial health or energy regulatory agency in Canada provided Ernst and her community or the many others harmed by frac’ing any help (and, the courts and Ernst’s own lawyers, Murray Klippenstein and Cory Wanless, lied and punished Ernst, devoutly pissing on the public interest and rule of law).

Our illegally frac’d drinking water aquifers remain frac’d by Encana/Ovintiv, a cowardly bully company that has run away to the USA.

Ernst’s presentation in Malton, North Yorkshire, UK. It sums things up.

To read more galling details about how Encana/Ovintiv and the regulators and courts treated the public interest and me, read Andrew Nikiforuk’s Slick Water.