Whole lotta bashing going on …

Jury Delivers Verdict In Oklahoma ‘Well-Bashing’ Case by Alex Cameron, September 01, 2017, News9

PIEDMONT, Oklahoma – A U.S. District Court jury delivered a verdict last month that is rippling through the state’s oil and gas industry.

The verdict was in favor of the owner of an old vertical well who had sued a large, independent producer for severely damaging his well during a horizontal frac job.

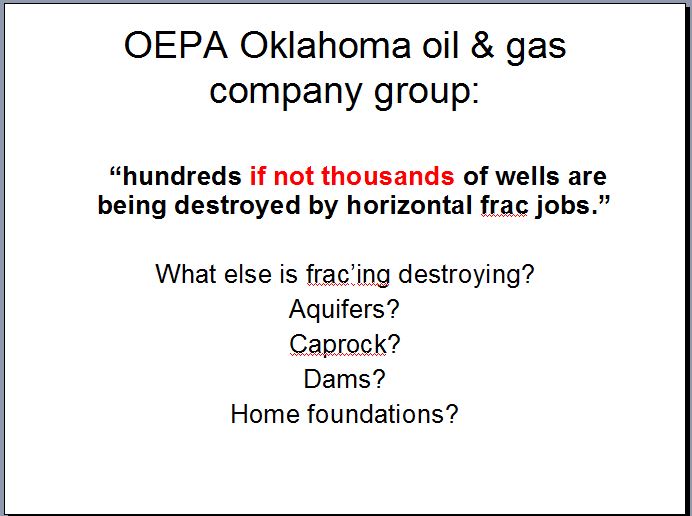

[Frac Bash Check:

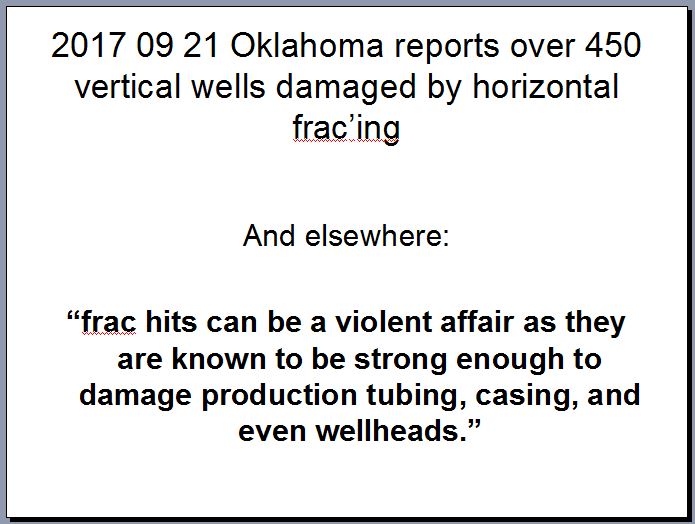

Slide from Ernst presentations in UK, October 2017

Refer also to: Nov 1, 2017: Now it’s oilmen who say fracking could harm groundwater

End Frac Bash Check ]

Such incidents, known within the industry as “well-bashing,” seem to be becoming increasingly common, which is why other vertical well owners hope this case will set a precedent, or at least send a strong message to the big horizontal drillers.

“The vertical wells can’t stand the fracs that they’re putting on these,” said Andy Sheen, the Edmond man who brought the lawsuit.

Sheen says he owns about a half-dozen vertical wells, mostly low production stripper wells similar to one he was checking on recently in Piedmont. The wells are his livelihood, which is why the phone call he got two years ago from a representative of a company drilling near him in Blaine County caused such concern.

“And he called and he said, ‘We fracked into your–we think we fracked into your well’,” recalled Sheen, “and I said, ‘Do what?'”

It appeared that the company, Denver-based Felix Energy, in completing a new horizontal well near Sheen’s vertical well, caused the casing to collapse at a depth of 4,700 feet, cutting off what Sheen says had been a modest, but steady flow of oil and gas.

Sheen says it was the third time one of his wells had been the victim of a frac hit. He says others have lost more wells than he has, but they have been unwilling to take the oil and gas companies, with their deep pockets, to court.

“They eat ya up with attorney’s fees, and people are just afraid, if they lose, it’ll break ’em,” Sheen explained. “I know I was, but I’d had enough.”

Sheen filed a civil suit in U.S. District Court (Western District of Oklahoma), naming Felix in three counts: private nuisance, subsurface trespass, and negligence. Eschewing a settlement offer from Devon Energy, which acquired Felix’s STACK assets shortly after the lawsuit was filed, Sheen took the case to trial, three weeks ago, and won.

Jurors ruled in favor of Sheen on the private nuisance and subsurface trespass counts; the negligence count was thrown out. Devon was ordered to pay $220,000 in damages.

“I do believe it will help,” said Joe Warren, who owns dozens of vertical wells and is a member of the newly-formed Oklahoma Energy Producers Alliance (OEPA).

Warren says more than twenty of his company’s wells, most of them in Kingfisher County, have been damaged or destroyed by horizontal frac jobs. He believes the judgment against Devon/Felix may lead to more small operators filing lawsuits. More than that, though, he hopes it will raise general awareness of the ‘well-bashing’ problem and ultimately help ensure the correlative rights of all stakeholders are protected.

“That’s not happening right now,” Warren insisted, “and there needs to be a change in practice at the Corporation Commission and a change of rules, if necessary.”

Officials with the Oklahoma Oil and Gas Association (OKOGA) [Lying Bully CAPP Cousin?] disagree, in part.

“There’s been this notion that somehow these wells are being damaged with no recourse,” said Chad Warmington, OKOGA President, “and I don’t think that that’s the case.”

OKOGA is an industry advocacy group whose members include Devon and many of the larger oil and gas companies that are doing much of the horizontal drilling in Oklahoma. Warmington says the horizontal wells his members are drilling are good for Oklahoma and, generally, good for all those with correlative rights.

Still, Warmington acknowledges the system could stand some tweaking.

“Technology is advancing so quickly, regulation hasn’t caught up, the process hasn’t quite come together,” Warmington stated, “but I’m pretty confident, based on our large members who are the most active in the state, they want to figure out a way to make this work better for everybody.”

Some of the frac interference cases are being settled privately, but Warmington understands that many small owners and operators feel there should be a better way to compensate them fairly when their wells are damaged.

“I think we agree with them, and want to come up with a process that helps to do that,” Warmington explained. “So, I don’t think you’ll see a bunch more lawsuits– I think what you’ll see is the Commission evolve its practices.”

The Oklahoma Corporation Commission, which regulates all drilling in the state, is currently gathering data on frac interference so that permitting guidelines might be tweaked, but commissioners say determining compensation for damaged wells is not in their purview.

“While we can set policy that may affect the way in which future wells are drilled,” said Commissioner Todd Hiett, “we don’t have jurisdiction, in terms of awarding damages or setting values on wells,”

Hiett says the Commission’s biggest concern right now, with regard to the well-bashing incidents, is the potential for harm to the environment — contamination of groundwater. He says they need more data on these events and thus are urging vertical well owners who feel they’ve been fracked into to report it to them. [Emphasis added]

Federal jury awards Oklahoma oil companies $220,000 in ‘well bashing’ case by Paul Monies, August 18, 2017, News OK

A federal jury has awarded two Oklahoma oil companies $220,000 in damages from a “well-bashing” incident in 2015 by a company later bought by Devon Energy Corp.

The jury awarded H&S Equipment Inc. and Mark Holloway Inc. the damages after a two-day trial earlier this week in federal court in Oklahoma City.

[Insanely, Ernst’s case, soon into it’s 11th year, still just on tortuously expensive preliminaries, IF the greedy, sanctimonious Canadian “justice” system ever lets Ernst have a trial (her lawsuit against Encana and the water regulator continue), is planned to take more than 25 days! ]

The companies said a hydraulic fracturing job in the summer of 2015 on a Felix Energy LLC horizontal well near one of their vertical wells in Blaine County overpressured the well and destroyed its production. They sought damages and lost profits in excess of $1 million for subsurface trespass, creating a private nuisance and negligence.

Devon spent $1.9 billion to buy Felix Energy in late 2015, a transaction that gave it another 80,000 net acres in Oklahoma’s STACK play. It also inherited the lawsuit, which was filed against Felix in November 2015.

The jury sided with H&S Equipment and Holloway on the subsurface trespass and nuisance claims. U.S. District Judge Joe Heaton ruled Devon wasn’t negligent as a matter of law.

Devon has not said if it plans to appeal the judgment.

“At this time, we’re unable to discuss the specifics of the case, which involves a well we acquired after it was drilled and completed,” Devon said in a statement Thursday. “When the case is finalized, we’ll be able to discuss the circumstances in greater detail. In any event, safe and responsible operations are our top priority wherever we operate.”

‘I didn’t know if I could hold out’

Andy Sheen, whose H&S Equipment and Holloway own and operate the Coffey No. 1-14 well in Blaine County, called the judgment a win for vertical operators. He predicted more lawsuits against horizontal producers after the verdict.

“There’s several different companies that have been fracked into, but the big boys will run you out of your business with their attorneys’ fees,” Sheen said Thursday in a phone interview. “I’d had enough. I didn’t know if I could hold out, but if I knew if I could last, I could prove they pressured me up to 2,200 pounds (per square inch) before they blew up my well. I thought I would get more money, but if I didn’t, it might also set a precedent.”

Sheen said he’s had two other vertical wells affected by nearby horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, a phenomenon known as “well bashing” or a “frack hit.” Sheen came to a settlement with another large, public company at one well. In the other case, he said wasn’t aware of the problems at that well in Kingfisher County until it was too late.

Sheen said he’s been in the oil business about 40 years as a plunger lift operator and owns and operates another half-dozen wells.

“I’m a one-man show and do everything by myself,” he said. “I fought this lawsuit by myself. Maybe now these other small operators won’t be scared to fight. I think I’ve opened the door for other people to try to defend themselves.”

In court filings, attorneys for Devon said H&S Equipment and Holloway didn’t mitigate the alleged damages by either evaluating the well, repairing it or reopening it. They said the plaintiffs appeared to pick an “overinflated” amount for lost profits based on past production, not future estimates of oil prices and decline curves, the term for a decline in output over time.

The judgment comes as the Oklahoma Corporation Commission works to finalize emergency rules to implement a new state law allowing longer lateral drilling in nonshale formations. The debate over Senate Bill 867 in this year’s legislative session was contentious and pitted smaller, vertical operators against larger horizontal drillers. [Emphasis added]

2 wells, 1 patch of dirt. Who gets the oil? by Mike Soraghan, October 31, 2017, E&E News

OKARCHE, Okla. — A unique set of rules has evolved in this oil-driven state that allows two companies to pump oil from the same patch of dirt, sometimes in the same formation.

But it’s not going smoothly. Instead, it has left a trail of older wells damaged by “frack hits,” flummoxed state regulators and started a civil war within the state’s singularly powerful oil industry.

The fallout has roiled a state where the small wildcatter is as revered as the family farmer, and aging pumpjacks dot the landscape like tobacco barns in the South. Most of those wells were drilled back when wells went one direction — straight down. And many decades-old wells still pump a few barrels a week.

But state leaders have allowed large independent producers, like Newfield Exploration Co., Devon Energy Corp. and Chesapeake Energy Corp., to drill long horizontal wells for up to 2 miles through those old oil fields.

Small producers complain the larger companies are siphoning off their oil and damaging their older, vertical wells with high-pressure hydraulic fracturing. They say state officials are allowing it, even encouraging it.

The horizontal wellbores are allowed as close as 600 feet to the vertical wells, sometimes closer. The underground fractures, created under about 10,000 pounds of pressure, sometimes reach vertical wellbores and flood them with sand and fluid.

“They know they’re going to ruin your well and they don’t care,” [Just like the companies and regulators know hydraulic fracturing ruins drinking water aquifers and drinking water wells. They don’t care about that either. Nor do the courts in Canada – judges are not even pretending to serve “justice” or trying to hide their obvious corruption (eg. justices knowingly publishing lies in Supreme Court Rulings, with lawyers knowing and saying nothing to protect their careers and pay cheques)] said Mike Cantrell, who helped lead an exodus of small drillers from the state’s largest oil industry trade group earlier this year. “This wouldn’t happen in Colorado, Texas or North Dakota.” [It most likely would and is]

Cantrell’s new group, the Oklahoma Energy Producers Alliance, commissioned a study estimating more than 400 wells have been damaged by such “frack hits” in just one county. An E&E News review found at least 10 state and federal lawsuits alleging that horizontal fracturing damaged vertical wells.

State oil and gas regulators say they’ve confirmed 20 such incidents, which sometimes lead to surface spills. Some vertical producers say frack hits could contaminate groundwater, though regulators say they have no proof of that. [Of course regulators would say that. They don’t look for the proof, and when it’s sent to them, they ignore it, so as to continue saying they have no proof]

Larger drillers say their smaller rivals are exaggerating the problem. But they say if state rules favor horizontal drillers, it’s because they have the same interests as the state — pumping as much oil out of the ground as quickly and efficiently as possible. Legislators and regulators at the Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC), they say, are simply changing with the times.

“The commission’s goal is to develop the resources of the state,” said Chad Warmington, president of the Oklahoma Oil and Gas Association, which represents the state’s large independent producers. “You cannot develop the resources of the state with vertical wells.”

None of the three elected commissioners agreed to an interview for this report. But a commission spokesman said the agency is just trying to implement what lawmakers have handed to them.

“It’s important to understand we didn’t make this law,” said OCC spokesman Matt Skinner. “We have to follow the law that was passed by the Legislature and signed by the governor.”

While Oklahoma’s situation appears to be unique, the clash shows that problems that can result from new drilling in old oil fields, and shows the shale boom has created a growing gap between large and small independent producers.

‘An art and a science’

In Okarche, about an hour west of Oklahoma City, the Cactus 142 rig is tunneling a 9-inch hole about 2 miles under the vast prairie.

The Newfield Exploration oil well is called the “CE Frederick 1508 1H-22XR.” It’s in Kingfisher County, the heart of what’s called the STACK, which stands for “Sooner Trend Anadarko Basin Canadian and Kingfisher Counties.” It’s the hottest play in Oklahoma right now, and among the hottest in the country.

The STACK, along with its neighbor play, the SCOOP (a similarly tortuous acronym that stands for “South Central Oklahoma Oil Province”), have led the revival of Oklahoma’s oil industry.

Newfield’s bet on the STACK has made the company, based near Houston in the Woodlands, Texas, the No. 1 oil producer in the state.

Part of that success is the ability to steer the drill bit underground with precision.

“It’s an art and a science,” Lloyd Hetrick, Newfield’s operations engineering adviser, said over the roar of the rig. “We can thread a basketball hoop from 2 miles away.”

The only well in the path of the CE Frederick is another Newfield well. The Cactus crew will bend — “slide,” in oil field jargon — the wellbore around it.

Changes to the law made by the Oklahoma Legislature in 2011 opened the door to companies drilling horizontal wells right through networks of vertical wells in existing oil fields. At first, the changes included only shale layers, where the vintage wells didn’t produce.

But in the past few years, as the large producers bounced back from a price slump, they’ve been more aggressive about drilling horizontally in some of the same formations as verticals. Earlier this year, the Legislature extended the same advantages to non-shale formations.

One small driller likened the changes to a city council permitting a new building to be constructed on top of another person’s building.

“The whole argument boils down to private property rights,” said Zack Taylor, who has a small family-run oil company in Seminole and is also a state representative. “You can’t step on someone’s property right to promote development.” [But oil and gas companies step on people’s property rights all the time, everywhere they operate, and more and more courts are too]

Larger drillers say there are protections in place to protect the smaller drillers.

To prevent damage, horizontal wells are supposed to stay at least 600 feet away from vertical wells, although OCC officials can waive the setback. Vertical operators can also buy into the new well.

If they don’t have the money to buy in, they can cut a deal with the operator, or OCC administrative law judges assign fair market value to their interest. The vertical company can keep producing from its well, if it doesn’t get damaged.

If it does get damaged, they say, the vertical driller still has an option — filing a lawsuit. [And destroy twenty years with stress and endless abuses by defendants and judges, and destroy finances to maybe get restitution that will nowhere near cover the legal fees to get there, never mind the damages suffered?]

“It is not the Wild West where the little guy is run over,” Hetrick said.

But it sure feels that way to Steve Altman.

The petroleum engineer is dealing with a well that has been hit three times. The first was a “bump,” Altman said. The second was a “hit.” The third was a “smash,” collapsing the well’s casing and ruining it.

That well had been producing about 40 barrels of oil a month. With natural gas production thrown in, that added up to $10,000 a month — a rounding error for Newfield, but a tidy sum for Altman and his business partners. And that’s only one of more than two dozen of their wells that have been damaged since 2014.

“I’ve never had a horizontal well nearby that didn’t hit me,” Altman said.

Altman, Cantrell and other vertical drillers scoff at the protections cited by large drillers, starting with state officials setting a value on their interests. The guidelines used by OCC administrative law judges are so restrictive, they say they get a fraction of the true value.

“The reddest of red states, and the government sets the price,” Cantrell quipped in an interview in Oklahoma City.

The 600-foot setback is cold comfort, they say, since fractures can travel many times farther than that.

A Newfield engineer testified in September that frack fluid has been found a mile from where it started. Small drillers say they’ve heard of fracks hitting wells several miles away.

And the larger companies don’t always accept the 600-foot setback because it means less oil. In the September OCC hearing, Newfield argued that unless the setback was waived for several wells, it would wind up leaving nearly $28 million worth of oil and gas in the ground. The judge rejected the waiver request. [What a surprise]

Some frack hits blast through the top of the vertical well itself and cause a spill at the surface. Ironically, the owners of the vertical well are usually held responsible for the spill cleanup, since it happened at their well. [Nasty! Just how big oil and gas producers like it!]

The OCC oil and gas regulators, now trying to finalize regulations from this year’s legislation, say they’re trying to address the problem, sometimes called “well bashing.”

But they say they lack the information they need. Often, they learn about frack hits only when they cause a spill at the surface. So the agency recently started collecting information on frack hits, creating a new form for vertical operators to report such incidents.

But those vertical operators say OCC officials should be preventing well bashing before it happens. They say the agency has the authority to keep the horizontal wellbores farther away from verticals in the first place.

“They shouldn’t be permitting those things knowing they’re going to destroy those vertical wells,” Cantrell said. [Like regulators shouldn’t be permitting frac’ing 100 metres from drinking water wells? Like regulators covering-up when companies illegally frac right into drinking water aquifers, repeatedly?]

A lobbying schism

The dispute is tearing away at the state’s long-dominant oil lobbying association — the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association, or OIPA.

For years, OIPA was pretty much the only game in town. But during the shale boom, the interests of large and small independent producers started to diverge.

In 2013, an older trade group got a new name — the Oklahoma Oil and Gas Association — and a new executive director, Warmington. Its old incarnation had long represented oil majors such as Exxon Mobil Corp. and BP PLC. Warmington started positioning OKOGA, as it’s called, as the voice of large independents.

Many of the larger companies were active in both groups. But last year, larger companies like Newfield, Devon and Chesapeake quit OIPA, concerned the group was too focused on the interests of small independents.

This spring, Cantrell led an exodus of small producers and formed the Oklahoma Energy Producers Alliance, or OEPA. He said about 15 of the more than 60 board members of OIPA left the board.

What changed is that OIPA had, after many years, endorsed legislation expanding the advantages for horizontal drilling, which then passed narrowly.

To A.J. Ferate, OIPA’s vice president of regulatory affairs, the group was simply keeping up with the times. He says OIPA is still the largest oil industry group in the state, and remains strong.

“It’s only natural for every industry to become more sophisticated over time,” Ferate said. “That’s true of oil and gas, too.”

But to Cantrell, the shift in position showed the association was no longer representing “the little guy who’s been here forever.”

That Cantrell would become the face of opposition to OIPA shows the depth of the political shift in the state. To many, the oilman from Ada, Okla., had embodied the OIPA. He represented the organization as chairman of many board committees and served a term in the 1990s as OIPA president.

In addition to challenging the new legislation for horizontal drillers, OEPA came out against a tax advantage for new wells cherished by the larger companies (Energywire, Sept. 25).

The organizations have traded contemptuous statements for months in press releases and social media posts. But the bitterness hit new heights in late August, when OIPA demanded that Dewey Bartlett resign from its board.

Bartlett, who runs a small oil and gas company, was mayor of Tulsa until 2016. He’s the son of a governor who was a founding member of OIPA. As a former president of OIPA, he has a lifetime membership on its board. But he also became a founding board member of OEPA.

OIPA President Tim Wigley wrote Bartlett to say he’d been seen at the state Capitol lobbying against OIPA-supported legislation.

“I’m requesting that you make a decision as to where you want to serve — with OIPA or OEPA — not both,” Wigley’s letter said.

Bartlett has not resigned from either.

To some, the infighting is a logical progression for an industry reviving domestic production after years of decline. To others, the “new normal” is dispiriting. But most agree that it means more big fights to come. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to:

2016 EPA fracking study:

6.3.2.3. Migration via Fractures Intersecting with Offset Wells and Other Artificial Structures

Leaking well, company draw state’s notice by Dennis Webbb, January 6, 2014, The Daily Sentinel

A state inspector last March determined Maralex Resources was in violation of a requirement for mechanical integrity testing for an oil and gas well where a leak was discovered Dec. 14 southwest of De Beque.

In addition, the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission in October fined Maralex $50,000 after finding the company had failed to comply with the same requirement in the case of nine other wells in Mesa and Garfield counties.

Also, the Bureau of Land Management says it has required the company to repair about 20 wells with small gas leaks over recent years in western Colorado.

Maralex’s history of problems concerns Commissioner Rich Alward of Grand Junction, who does oil and gas reclamation consulting work. He says Maralex’s problems go even further and he sees them firsthand.

“They’ve got a number of well pads with failed reclamation and that are poorly maintained, they have old equipment lying on their well pads, and that (observation) is from my actual being on the ground, seeing the weed cover, lack of reclamation, lack of revegetation,” he said.

He said that most of the time when he’s working on another project in the field, “I can identify a Maralex (well) pad from a mile away.”

Gas and fluids were discovered leaking around the problem Maralex well on federal land on Jaw Ridge about seven miles southwest of De Beque. It was drilled in 1981 and was shut shortly thereafter but remained capable of production. Authorities are investigating whether the recent hydraulic fracturing of a horizontal Black Hills Exploration & Production well that passed an estimated 400 feet within the Maralex well underground may have triggered the leak.

Some fluids initially ran off the pad, but the BLM says no surface waters appear to have been impacted. The well was opened and flow is being diverted to a containment pit, and work has been ongoing to permanently plug the well based on a BLM order. So far, two, 200-foot plugs have been installed that have isolated the Dakota sandstone target production zone of the well. A plug in the above-lying Mancos shale formation, which the Black Hills well was targeting a part of, probably will be installed today.

The well has leaked thousands of gallons.

The BLM saw no structural problems with the well during a routine inspection in July.

The commission requires companies to test wells for mechanical integrity within two years of their initially being shut in, and every five years thereafter. Such tests are designed to ensure the soundness of the well casing and the cement sealing around it.

Commission records indicate the Maralex well was shut in in 1983.

“It should have been tested in 1985 and every five years since then,” Alward said.

The regulators’ records indicate the well was drilled by the Golden-based Adolph Coors Co. That company was associated with the family behind Coors beer.

Disputes over access

In 1992, the well was taken over by GASCO, Inc., which was a subsidiary of KN Energy. In 1995, its operation transferred to KN Production Co., and Ignacio-based Maralex acquired it later that year.

Oil and gas commission records show Maralex owns more than 220 wells in Mesa, Garfield, Rio Blanco and La Plata counties.

The company hasn’t been available for comment. However, in a 2012 letter to a commission official, discussing its work plan for inactive wells in the Piceance Basin, it said it is operating most of its Piceance wells in the red due to low natural gas prices.

“This does not lend itself to an environment by which we have positive economics to complete well work,” the company wrote.

It also cited difficulties getting to many of its wells due to access disputes with two ranch owners.

In 2009, Garfield County and the BLM dealt with problems at a Maralex site in the Soldier Canyon area off Douglas Pass, including poor fencing that let deer and a bear get into a fluid-filled pit. The company reportedly at first cited a lack of money to address the problems, but at least some problems eventually were fixed.

Following discovery of the December leak, commission inspectors have found other problems at the Jaw Ridge well site ranging from a small hole in a tank, to a lack of an emergency contact number on signage, to the need to remove unnecessary equipment.

In this summer’s inspection, the BLM found some deficiencies such as weeds on site.

Plug or produce

According to a statement from the BLM, provided by spokesman David Boyd, Maralex operates 110 oil and gas wells involving federal lands or minerals in western Colorado.

“Of these, 24 are producing and 86 are shut-in. Forty of the shut-in wells have been shut-in for more than 20 years. The majority of their wells were obtained in the last 15 years from other operators,” the statement said.

“BLM has been working with Maralex and COGCC to resolve the issues related to these older shut-in wells. BLM met with Maralex on September 10, 2013 with the goal of developing a strategy for addressing their shut-in wells. We want them to develop a strategy to either plug the wells or put them into production over the next five years. Maralex has started this process and is planning to plug three wells in the De Beque area this month.”

The BLM said it can’t inspect each Maralex well each year, but typically does so every two years.

“We have documented some issues with their wells and well pads during these inspections,” the agency said, and it has written up what it calls instances of non-compliance.

“Problems we’ve documented and required them to address include ensuring containment berms and containment pits are adequate, keeping their equipment painted to avoid rust, and labeling tanks and other structures adequately. In recent years we have discovered about 20 wells that had small gas leaks, which we required them to repair.

“Surface condition of the pads, including reclamation, is one of the issues we are also concerned about. When a company plugs a well, it would be required to complete final reclamation.”

The BLM doesn’t require mechanical integrity tests over certain intervals of time.

“We typically require them on a shut-in well before an operator takes action such as plugging it or putting it into production. If an inspection of a shut-in well suggests there could be a problem, we could require one be done,” the agency said in its statement.

Comment by Claudette Konola – January 7, 2014

This story points to a problem with how we lease public lands and how we manage them once they have been leased. There is no requirement that the owner of a well be financially secure enough to deal with problems that may develop, and the current bonding requirement is inadequate to protect the taxpayer. Interesting that there was Coors money invested in the original well. They made money while it was producing, then sold it to another company to get out from under the responsibility of reclaiming the site. How can the big, responsible oil and gas companies condone this kind of behavior? It gives them a bad name.

2013 08 05: When 2 wells meet, spills can often follow

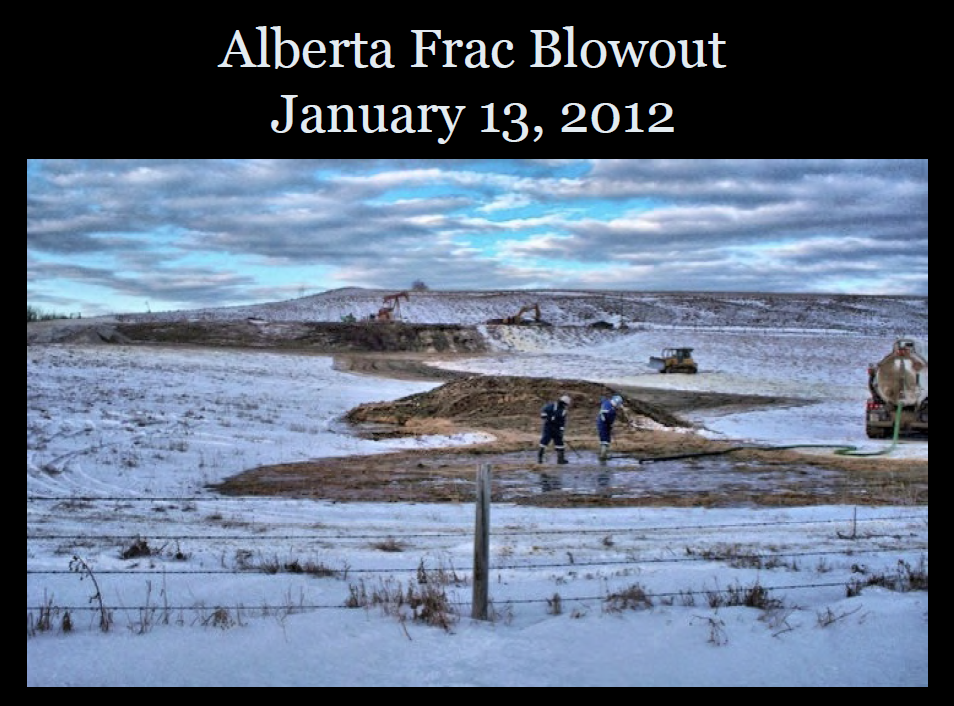

Slides from Ernst presentations

2012 06 25: Methane Geyser in PA: Shell Fracking Operation Suspected

EcoWatch reports that the Pennsylvania DEP is investigating a suspected methane migration problem which caused a 30-foot-tall methane-driven geyser to erupt from the side of a local road, and contaminated a water well at a hunting cabin in Union Township.

The suspected source of the methane is a frack site operated by Shell on the Guindon farm in Union Township

NPR reports that Tioga County Emergency Services Coordinator Denny Colegrove suspects that an unmapped, abandoned gas well more than 70 years old is part of the problem.

The geyser is now under control, and evacuation is being planned for residents within a 1-mile radius. Shell is flaring gas

from several wellsites in the vicinity in an attempt to lower pressure and reduce the methane leaks at the surface. (We’re not sure why this would work; it suggests all of these wells are in communication with each other, the gas reservoir, and the surface — a highly undesirable situation. Can anyone explain?)

If the cause is determined to be a fracking operation intersecting an unmapped, improperly abandoned well, then this is great concern for the future of fracking in a state that is littered with thousands of abandoned wells.

Slide from Ernst presentations