Influx of 4,500 workers raises fears of violence against women in B.C.’s northwest, Women’s shelters in Kitimat, Terrace already operate above capacity while concerns about ‘man camps’ persist by Michelle Ghoussoub, CBC News, Mar 06, 2020

This story is part of Stopping Domestic Violence, a CBC News series looking at the crisis of intimate partner violence in Canada and what can be done to end it.

Kitimat, B.C., feels like a town of men.

In fast food joints and corporate buses shuttling workers around the North Coast town, employees of the LNG Canada project stand out with their uniformity. Most sport the obligatory heavy duty boots and coats worn by workers throughout B.C.’s north as they cope with a waning winter.

The $40-billion dollar liquefied natural gas project will employ about 7,000 workers at the peak of construction, flying 4,500 people into town for rotating two-week shifts. Around 80 per cent of workers are men, swelling the size of Kitimat, whose population is normally just over 8,000.

The influx of people into town has mixed consequences, providing a boon to local businesses and raising environmental questions. But there’s another, more worrying, trend.

Over the past two years, Kitimat and nearby Terrace’s shelters for women fleeing violence have frequently been overwhelmed while concerns about harassment from incoming workers grows.

“We have been at or over capacity most nights of the year for the past two or three years,” said Michelle Martin, who works at the Tamitik Status of Women.

Jessica McCallum-Miller, Terrace’s 26-year-old, first Indigenous city councillor, says she’s worried the influx of people into town is also increasing instances of violence outside of intimate relationships.

She says she’s felt threatened by men who are strangers.

“As a young Indigenous woman, I’m actually facing some stalking, violence in my community, I’ve been harassed by unknown men, not from this community,” she said, adding she and others have been followed by men in cars.

“I don’t know if they work for industry, I don’t know who they are,” she said, her shock of blue hair in contrast to Terrace city council’s stark chambers.

LNG Canada has brought prosperity to the town which has already experienced several cycles of boom and bust that accompany natural resource projects.

Martin says the project has also “unintentionally affected” women fleeing violence by driving up the price of housing. Other community members say the project has sparked fears that “man camps” — temporary housing for predominantly male workers — will make the area dangerous for women.

LNG Canada says it knows major natural resource projects can put a strain on small towns, and that it takes the safety of women and Indigenous people seriously. Susannah Pierce, LNG Canada’s director of corporate affairs, says it’s not true that workers pose a threat to women. ![]() If so, then LNG Canada is lying when it claims “it takes the safety of women and Indigenous people seriously.”

If so, then LNG Canada is lying when it claims “it takes the safety of women and Indigenous people seriously.”![]()

“The view that these are just cauldrons of testosterone and these men are out to get the women is wrong,” she said.

Turned away

Kitimat is a hilly cluster of faded pastel homes and newer, low-rise apartments tucked at the head of B.C.’s Douglas Channel, in the traditional territory of the Haisla Nation. In late February, the snow banks are several feet high and covered in a layer of winter grime.

A public work road snakes out of town toward the project site, past a dozen orange hydraulic cranes known as cherry pickers, and a collection of blue and white temporary housing units where workers will live come April.

Somewhere in town, at a secret location, is Kitimat’s women’s shelter. It’s funded for eight beds but squeezes in a ninth, and is officially over capacity when that last bed is full. The shelter has had to turn away dozens of women and their children over the past two years.

Its director Martin says that’s an alarming number, considering many women facing abuse from a partner can’t or don’t leave, immediately or ever.

“There’s this assumption that when violence occurs people want the relationship to stop or want to leave when in fact, more often than not, women want the relationship to continue — they want the violence, the behaviour, the abuse to end,” she said, adding it’s even less likely women will leave in a town as small as Kitimat, where it’s near impossible to stay anonymous.

Leah Levac, an associate professor at the University of Guelph who studies the experiences of women in towns hosting natural resource projects, says research shows domestic violence rates in the north are “related to resource] extraction.”

She said locals who can’t work in industry come under pressure when workers with higher incomes flood the town, driving up the cost of housing. While nationally the average median total income for women is about 68 per cent of that earned by men, in Kitimat it’s 49 per cent, making it difficult for women to strike out on their own.

Martin said natural resource project work is inherently precarious, and those who do land jobs suffer mentally when projects wrap up.

“For somebody who has low coping mechanisms or emotional regulation, if they feel bad about themselves and see others prospering, certainly that can translate to violence,” she said.

‘Man camps’ and misconceptions

Domestic violence is one, but not the only, concern.

The National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s report released in June 2019 explicitly warned “increased crime levels, including drug- and alcohol-related offences, sexual offences, and domestic and ‘gang’ violence, have been linked to ‘boom town’ and other resource development contexts,” and urged companies to consider the safety of Indigenous women in all stages of project planning.

LNG Canada said it’s working to mitigate impacts on Kitimat by housing workers at a camp — referred to as the lodge — near its work site outside of town. It was also the first company to undergo, as part of its environmental assessment, another process examining social impacts on the community.

Company spokesperson Pierce says there’s a zero-tolerance policy for violence, harassment, and bullying both “inside and outside the fence,” in reference to behaviour both on and off the work site.

“The view that you have all these men sort of coming in to huddle together and [do] bad things, I think that’s a misconception. The kinds of folks that come in to work on these jobs, they have families too, and daughters too,” she said. ![]() Since when does being married or having children stop rapists and pedophiles? The men that raped/sexually assaulted me when I was a child were married Christians with children.

Since when does being married or having children stop rapists and pedophiles? The men that raped/sexually assaulted me when I was a child were married Christians with children.![]()

Still, in a small town where the ratio of women to men is warped, it can be difficult to dispel a sense of unease.

“When we speak with both Haisla and settler women in this community, they will flag that their perception of increased instances of feeling unsafe […] are connected to this influx of people,” said Levac, who has travelled to Kitimat several times to interview women.

‘Swept under the rug’

Before running for city councillor, McCallum-Miller worked in the donation room of Terrace’s shelter for women. Still in her early 20s and not formally trained as a social worker, she’d often find herself counselling women fleeing violence, as the shelter struggled to keep up with the demand for services.

It’s a memory she’s carried with her as she ran for office, and as she reads about how projects have put pressure on other towns.

“I know that there’s domestic violence, I know that there’s sexual violence and I know that we’re being extremely impacted by this, especially Indigenous women. And a lot of time it’s swept under the rug,” she said. ![]() Of course it’s covered-up, with the RCMP looking the other way, perhaps raping along with the oil patch men. Can’t let rape of women and children in Canadian boom towns interfere with the profits of (mostly foreign) rich!

Of course it’s covered-up, with the RCMP looking the other way, perhaps raping along with the oil patch men. Can’t let rape of women and children in Canadian boom towns interfere with the profits of (mostly foreign) rich!![]()

Despite her reservations, McCallum-Miller says she’s still undecided about how the project will affect her community. Kitimat and Terrace have already been through multiple cycles of boom or bust, and longtime residents know other hardships come when well-paying jobs dry up.

Pierce’s voice swells over the phone as she emphasizes that she wants Kitimat’s experience with LNG Canada to be different.

“We want people to be safe. We want women to be safe. And Indigenous people to be safe,” she said.

If you need help and are in immediate danger, call 911. To find assistance in your area, visit sheltersafe.ca or http://endingviolencecanada.org/getting-help.

Refer also to:

EnCana donates $200 to transition home for women and children in Dawson Creek IMAGINE ENCANA/OVINTIV’S PHENOMENAL GENEROUSITY! 200 DOLLARS! IF OIL PATCH WORKERS PAID APPROPRIATE PROSTITUTE FEES TO THE LOCAL WOMEN AND CHILDREN THEY RAPE, I EXPECT THE TALLY WOULD BE IN THE MILLIONS OF DOLLARS.

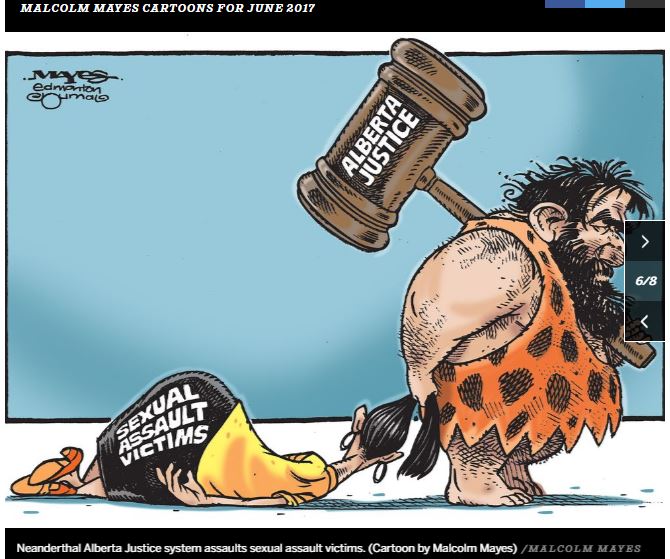

“It’s the judges!” enabling rape and murder of women. No kidding. In Canada too.

Law Society of Ontario a Pedophile Ring? Racism, misogyny *and* enabling sexual abuse of children? Ottawa lawyer, John David Coon, in custody for sex crimes against four-year old daughter of one of his clients. Law Society documents reveal they gave Coon licence to practise law despite knowing of his prior criminal conviction for sexually assaulting another child. HOW MANY CANADIAN JUDGES ARE PEDOPHILES AND OR RAPISTS?

MUST WATCH! ‘This Hour Has 22 Minutes’ Sketch: “Judges: a danger to Canadian women”

New Study: Again, frac’ing linked to increased sexually transmitted disease