“Methane Emissions from abandoned oil and gas wells in Canada and the US” by James P. Williams, Amara Regehr and Mary Kang in Environmental Science and Technology, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.0c04265

Methane emissions from abandoned oil and gas wells underestimated, Uncertainty about annual methane emissions from abandoned wells in US and Canada highlights need for better measurements Jan 20, 2021, McGill Newsroom

Bubbles of methane gas in water around an unplugged oil/gas well in Pennsylvania. CREDIT: Mary Kang

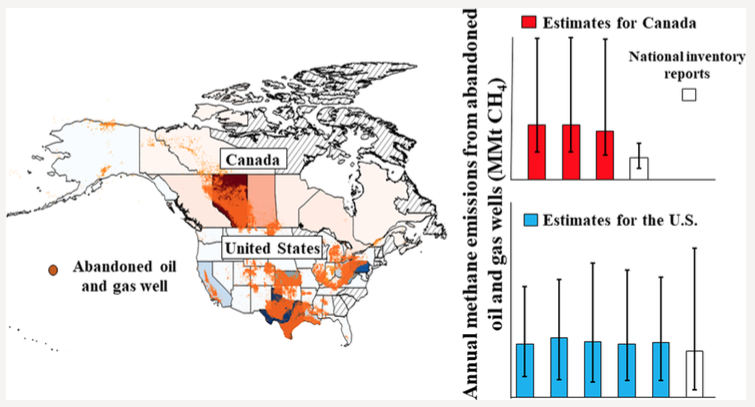

A recent McGill study published inEnvironmental Science and Technology finds that annual methane emissions from abandoned oil and gas (AOG) wells in Canada and the US have been greatly underestimated – by as much as 150% in Canada, and by 20% in the US. Indeed, the research suggests that methane gas emissions from AOG wells are currently the 10th and 11th largest sources of anthropogenic methane emission in the US and Canada, respectively. Since methane gas is a more important contributor to global warming than carbon dioxide, especially over the short term, the researchers believe that it is essential to gain a clearer understanding of methane emissions from AOG wells to understand their broader environmental impacts and move towards mitigating the problem.

Multiple sources of uncertainty

The researchers show that the difficulties in estimating overall methane emissions from AOG wells in both countries are due to a lack of information about both the quantities of methane gas being emitted annually from AOG wells (depending on whether and how well they have been capped), and about the number of AOG wells themselves.

“Oil and gas development started in the late 1850s both in Canada and the US,” explains Mary Kang, the senior author on the paper and an assistant professor in the Department of Civil Engineering at McGill. “Many companies that dug wells have come and gone since then, so it can be hard to find records of the wells that once existed.”

Thousands of undocumented AOG wells

To determine the number of AOG wells, the researchers analyzed information from 47 state, provincial or territorial databases as well as from research articles and national repositories of drilled and active wells in the US and Canada.

They found that, of the over 4,000,000 AOG wells they estimate to exist in the US, more than 500,000 are undocumented by the relevant state agencies. A similar picture emerges in Canada. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) only has records going back to 1955 although historical documents confirm that oil and gas activity in Canada began in the 1850s.

Based on the various sources they examined, the researchers estimate that there are over 370,000 AOG wells in Canada. Over 60,000 of are not included in databases of provincial or territorial agencies.

More methane gas emitted by AOG wells than shown by government records

To gain a better sense of exactly how much methane was being emitted from the wells, the researchers analyzed close to 600 direct measurements of methane emissions drawn from existing studies covering the AOG wells in the states of Ohio, Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, Oklahoma, West Virginia and Pennsylvania in the US and from British Columbia and New Brunswick in Canada. They developed different scenarios to attribute different levels of annual methane emissions to the wells, depending on what is known of the plugging status of the wells as well as whether they were oil or gas wells.

“We see that methane emissions from abandoned wells can vary regionally, highlighting the importance of gathering measurements from Texas and Alberta which have the highest percentage of wells in the U.S. and Canada and no prior measurements,” adds James P. Williams, the first author on the study and a Ph.D. student in the Department of Civil Engineering at McGill.

All five scenarios show annual emissions of methane gas from AOG wells in the US that are approximately 1/5th higher than the amount that the US EPA’s estimates for 2018. In Canada, the study findings suggest that methane emissions from AOG wells in 2018 were nearly three times higher than estimated by Environment and Climate Change Canada.

“As society transitions away from fossil fuels, the millions of oil and gas wells around the world will be abandoned,” says Kang. “It is critical to determine the climate, air, water and other environmental impacts of these wells quickly.”

Canada underestimating methane emissions from orphan wells by as much as 150%, study finds by Nichola Groom, Reuters, Jan 20, 2021, The Globe and Mail

Methane leaking out of the more than 4 million abandoned oil and gas wells in the United States and Canada is a far greater contributor to climate change than government estimates suggest, researchers from McGill University said on Wednesday.

Canada has underestimated methane emissions from its abandoned wells by as much as 150 per cent, while official U.S. estimates are about 20 per cent below actual levels, the study, published in Environmental Science and Technology, found.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Environment and Climate Change Canada did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the study.

More than a century of oil and gas drilling has left behind millions of abandoned wells around the globe, posing a serious threat to the climate that governments are only starting to understand, according to a Reuters special report last year.

Methane has more than 80 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide in its first 20 years in the atmosphere.

In 2019, methane emissions from abandoned wells were included for the first time in U.S. and Canadian greenhouse gas inventories submitted to the United Nations.

But the McGill study found there are about 500,000 wells in the United States that are undocumented along with about 60,000 in Canada. It also found that the EPA and ECCC had come up with emissions estimates that were far too low – a conclusion the researchers said was based on their own analysis of emissions levels from different types of abandoned wells in seven U.S. states and two Canadian provinces.

Emissions measurements were also not available from major oil and gas-producing states and provinces like Texas and Alberta, adding to uncertainty around the official data, the study said.

The study was co-authored by McGill professor Mary Kang, who in 2014 was the first to measure methane emissions from old drilling sites in Pennsylvania

Gas Companies Are Abandoning Their Wells, Leaving Them to Leak Methane Forever, Just one orphaned site in California could have emitted more than 30 tons of methane. There are millions more like it by Mya Frazier, September 17, 2020, Bloomberg Green

The story of gas well No. 095-20708 begins on Nov. 10, 1984, when a drill bit broke the Earth’s surface 4 miles north of Rio Vista, Calif. Wells don’t have birthdays, so this was its “spud date.”

The drill chewed through the dirt at a rate of 80 ½ feet per hour, reaching 846 feet below ground that first day. By Thanksgiving it had gotten a mile down, finally stopping 49 days later, having laid 2.2 miles of steel pipe and cement on its way to the “pay zone,” an underground field containing millions of dollars’ worth of natural gas.

It was ready to start pumping two months later, in early January. While 1985 started out as a good year for gas, by its close, more than half the nation’s oil and gas wells had shut down. How much money the Amerada Hess Corp., which bankrolled the dig, managed to pump out of gas well No. 095-20708 before that bust isn’t known. By 1990 the company, now called simply Hess Corp., gave up and sold it. Over the next decade or so, four more companies would seek the riches promised at the bottom of the well, seemingly with little success. In 2001 a state inspector visited the site. “Looks like it’s dying,” he wrote.

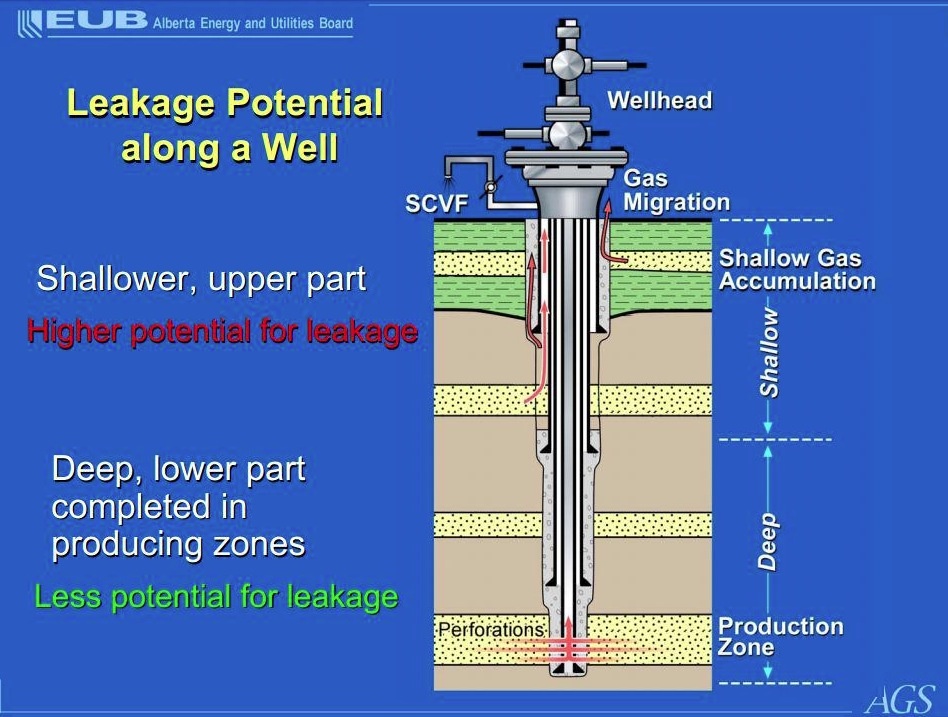

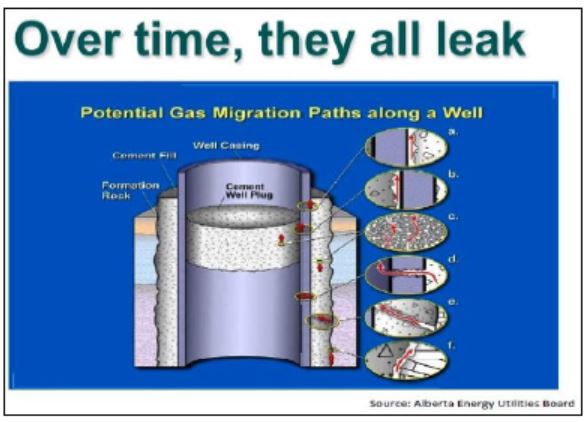

Gas wells never really die, though. Over the years, the miles of steel piping and cement corrode, creating pathways for noxious gases to reach the surface.

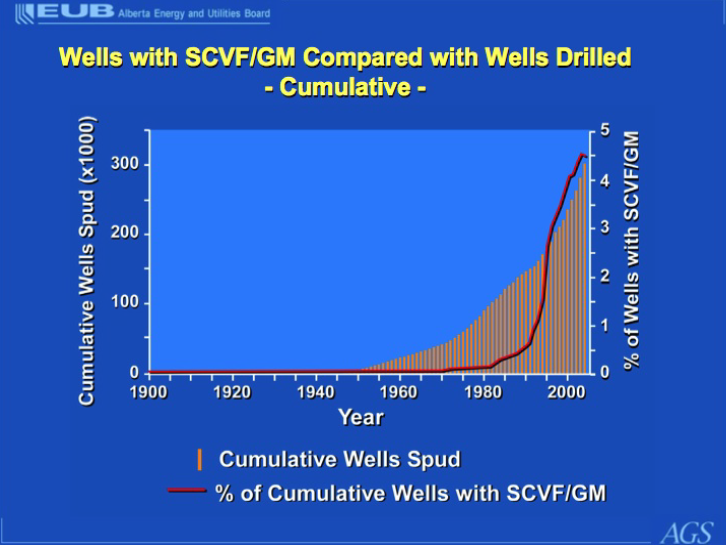

Slides from 2007, Alberta’s energy regulator has known for years how serious a problem industry’s methane leakers are but synergy and propaganda makes it all better:

The most worrisome of these is methane, the main component of natural gas. If carbon dioxide is a bullet, methane is a bomb. Odorless and invisible, it captures 86 times more heat than CO₂ over two decades and at least 25 times more over a century. Drilling has released this potent greenhouse gas, once sequestered in the deep pockets and grooves of the Earth, into the atmosphere, where it’s wreaking more havoc than humans can keep up with.

Well No. 095-20708 is also known as A.H.C. Church No. 11, referring both to Hess and to Bernard Church, who like so many in California’s Sacramento River Delta sold his farmland but retained the mineral rights in the hope that they’d make his family rich. The Church well is a relic, but it’s not rare. It’s one of more than 3.2 million deserted oil and gas wells in the U.S. and one of an estimated 29 million globally, according to Reuters. There’s no regulatory requirement to monitor methane emissions from inactive wells, and until recently, scientists didn’t even consider wells in their estimates of greenhouse gas emissions. …

In the past five years, 207 oil and gas businesses have failed. As natural gas prices crater, the fiscal burden on states forced to plug wells could skyrocket; according to Rystad Energy AS, an industry analytics company, 190 more companies could file for bankruptcy by the end of 2022. Many oil and gas companies are idling their wells by capping them in the hope prices will rise again. But capping lasts only about two decades, and it does nothing to prevent tens of thousands of low-producing wells from becoming orphaned, meaning “there is no associated person or company with any financial connection to and responsibility for the well,” according to California’s Geologic Energy Management Division.

“It’s cheaper to idle them than to clean them up,” says Joshua Macey, an assistant professor of law at the University of Chicago, who’s spent years studying fossil fuel bankruptcies. “Once prices increase, they could be profitable to operate again. It gives them a strong reason to not do cleanup now. It’s not orphaned yet, although for all intents and purposes it is.”

The life cycle of the Church well exemplifies this systemic indifference. Hess’s liability ended when it sold more than 30 years ago; the last company to acquire the lease, Pacific Petroleum Technology, which took over in 2003, managed to evade financial responsibility entirely as the well’s cement and steel piping began to corrode. Letters from state regulators demanding that the company declare its plans for the well went unanswered. In November 2007 the state issued a civil penalty of $500 over Pacific’s failures to file monthly production reports on the well. Instead of paying, Pacific requested a hearing, at which a representative testified that there was still $10 million worth of natural gas waiting to be pumped and promised the company would secure funds, make necessary repairs, and start producing again. The state was unconvinced and demanded Pacific plug the well. Another decade passed. The company never pumped a single cubic foot of gas and made no effort to plug the well. (Representatives of Pacific couldn’t be reached for comment.)

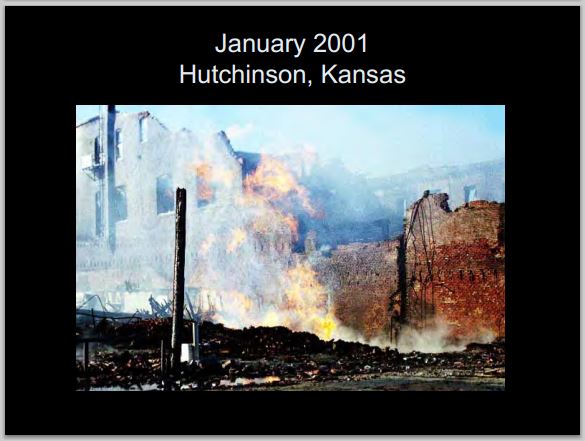

If Church were the only neglected well, it would be inconsequential. But these artifacts of the fossil fuel age are ubiquitous, obscured in backyards and beneath office buildings, under parking lots and shopping malls, even near day-care centers and schools in populous cities such as Los Angeles, where at least 1,000 deserted wells lie unplugged. In Colorado an entire neighborhood was built on top of a former oil and gas field that had been left off of construction maps. In 2017 two people died in a fiery explosion while replacing a basement water heater.

These kinds of headline-grabbing episodes are anomalies, but all this leaking methane also has dire environmental consequences, and the situation is likely only to get worse as more companies fail. “The oil and gas industry will not go out with a bang,” Macey adds, “but with a whimper.” As it does, the wells it orphans will become wards of the state.

Days before the 33rd anniversary of Church’s spud date, in November 2017, Eric Lebel, a researcher with the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences at Stanford, arrived at the wellhead. The rusted 10-foot structure—a “Christmas tree,” as it’s called in the industry—loomed over him.

While Lebel knew the well’s depth, it was still hard for him to envision its scale. “If you don’t see it, you don’t think about it,” he says later. “What’s underground is impossible to imagine.” The Earth’s interior has been unfathomably scarred by hydrocarbon infrastructure, he says. For almost two centuries, since the drilling of the first gas well in 1821, the fossil fuel industry has treated the planet like a giant pincushion. The first U.S. gas well in Fredonia, N.Y., extended only 27 feet underground, but drilling since has gone ever deeper. Ten-thousand-foot wells like Church are common today.

Now imagine each of those pins in the global pincushion is a straw inside a straw. In Church’s case, the outer straw is 7.625 inches in diameter and made of steel, encased in cement; inside is a 2.375-inch-wide steel tube. The deeper the well, the more the heat and pressure rise. At Church’s deepest point, 10,968 feet, the temperature likely exceeds 200F. The weight of the Earth exerts more and more pressure as the well goes deeper—reaching about 5 tons per square inch at the bottom. That’s the equivalent of four 2,500-pound cars on your thumb. All of this puts a huge amount of stress on that underground infrastructure. As it breaks down, eventually it begins to leak.

Astonishingly, no one had even bothered to ask how much until the past decade. In 2011, Mary Kang was a Ph.D. student at Princeton modeling how CO₂ might escape from underground storage vessels after being captured and buried. She looked for similar models on methane and came up with nothing; some of the industry sources she spoke with were confident that it wasn’t much—and that even if it was, technology existed that could fix it. “It’s one thing to assume,” Kang remembers thinking to herself. “It’s another thing to go get empirical data.”

Kang went to Pennsylvania, where boom and bust cycles over the years have left a half-million gas wells deserted. Of the 19 she measured, three turned out to be high emitters, meaning they released three times more methane into the atmosphere than other wells in the sample. “There were no measurements of emissions coming out of these wells,” she says. “People knew these wells existed, they just thought what was coming out was negligible or zero.” By scaling up her findings, Kang was able to estimate that in 2011, deserted wells were responsible for somewhere from 4% to 7% of all man-made methane emissions from Pennsylvania.

Those findings inspired Lebel and other researchers in the U.S. and worldwide to start taking direct methane measurements. The industry responded by ignoring them and fought fiercely against the Obama administration’s efforts to start regulating methane emissions. (A 2016 rule requiring operators to measure methane releases at active wells and invest in technology to prevent leaks was summarily overturned by the Trump administration at the beginning of August.)

Meanwhile, scientists trudged on. So far researchers have measured emissions at almost 1,000 of the 3.2 million deserted wells in the U.S. In 2016, Kang published another study of 88 abandoned well sites in Pennsylvania, 90% of which leaked methane.

Internationally, researchers tracked increasingly bad news. German scientists discovered methane bubbles in the seabed around orphaned wells in the North Sea. Taking direct measurements of 43 wells, they found significant leaks in 28. In Alberta, researchers estimated methane leaks in almost 5% of the province’s 315,000 oil and gas wells. ![]() It’s much worse than that in numerous areas.

It’s much worse than that in numerous areas.![]() In the U.K., researchers found “fugitive emissions of methane” in 30% of 102 wells studied. Such findings are both a threat and an opportunity, says Lebel, who considers abandoned wells the easiest first step to cutting methane emissions globally. That’s what brought him to Church in the first place.

In the U.K., researchers found “fugitive emissions of methane” in 30% of 102 wells studied. Such findings are both a threat and an opportunity, says Lebel, who considers abandoned wells the easiest first step to cutting methane emissions globally. That’s what brought him to Church in the first place.

According to his field logs, Lebel spent his first hour on site building a secure air chamber using a Coleman canopy tent draped in tarps, which he held in place with sandbags. Inside the tent, fans effectively created a convection oven of rapidly circulating air. As he worked, a farmer who leases the land wandered over. Be careful, he warned Lebel. Sometimes fire comes out of that well. Just yesterday he’d seen a plume of flames erupt from it, he said.

At 3:41 p.m., using an instrument that resembles a desktop computer with an abundance of ports, Lebel took his first methane measurement. “We knew right away it was a major leaker,” he recalls. It exceeded the instrument’s threshold of 50 parts per million almost immediately. Lebel collected air samples in tiny glass vials to take back to his lab. The analysis was damning: Two hundred and fifty grams of methane were flowing out of the well each hour. A rough calculation shows that over a decade and a half the Church well had likely emitted somewhere around 32.7 metric tons of methane, enough to melt a sizable iceberg.

Despite the flurry of recent research, the full scale of the emissions problem remains unknown. “We really don’t have a handle on it yet,” says Anthony Ingraffea, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Cornell who’s studied methane leaks from active oil and gas wells for decades.

“We’ve poked millions of holes thousands of feet into Mother Earth to get her goods, and now we are expecting her to forgive us?”

There’s no easy way to bring up the thousands of feet of steel and cement required to carry gas out of a well as deep as A.H.C. Church 11. That means the only way to keep the well from leaking is to fill it up. Plugging a well costs $20,000 to $145,000, according to estimates by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. For modern shale wells, the cost can run as high as $300,000.

On a Wednesday morning near the end of June 2018, a crew of workers from the Paul Graham Drilling & Service Co., hired by the state of California after Pacific Petroleum failed to respond to years of notices, arrived at the well site. As they would on any job, they first dropped a “string,” a lengthy metal cable, into the well; in ideal circumstances, it’d be a straight shot to the bottom. But not that day.

Well records indicate that a “packer,” a ring-shaped device used to create a seal between the outer and inner straws of gas wells, had been installed about 7,000 feet down. It would have to come out first, or they wouldn’t be able to get the cement all the way to the bottom. When they tried to pull out the packer, the string broke.

The tiny packer, just 2.5 inches wide, stayed stuck for weeks. As the crew tried to get it out, tubing inside the well broke—“structurally compromised due to corrosion,” they told California’s Department of Conservation in the work log they submitted. They were forced to go “fishing,” using specialized tools to retrieve the tubing, piece by broken piece. But the packer was still in there. Eventually they used even more specialized tools to grind it away.

It wasn’t until July 26, almost a month after workers arrived at the Church site, that they were able to start “running mud,” the industry term for pumping cement into the outer straw. This straw had been purposely perforated to allow oil and gas to flow from the pay zone into the well. The plugging cement is supposed to accumulate upwards as more gets pumped in. But if it leaks off into that porous pay zone, no matter how much mud the team runs, it simply disappears. Unless the cement and other sealants reached every nook and cranny, the site might continue to leak.

Thankfully, Church filled easily, requiring 36,500 pounds of cement. The unforeseen difficulties added $171,388 to Paul Graham’s original estimate, raising the total bill to $294,943, more than double the crew’s $123,555 bid. (Neither the cleanup company nor the state representatives who oversaw the work responded to interview requests.) Ingraffea examined the myriad work orders from the job and called it a “well from hell.”

By late August, almost two months after they arrived at the Church site, the crew had cut off the Christmas tree and welded a half-inch-thick steel plate to the top of the wellhead. It had taken nine days longer to fill the well than it had to drill it in the first place. Looking across the landscape today, it’s as though Church never existed.

The atmospheric evidence, of course, shows otherwise.

The cost to plug just California’s deserted wells—an estimated 5,500—could reach $550 million, according to a report released earlier this year. While not an insignificant price tag, the real shock would come if the industry collapses and walks away for good. In that doomsday scenario, the costs to plug and decommission 107,000 active and idled wells could run to $9 billion. And yet so far in 2020, California has approved 1,679 new drilling permits.

“We make the same mistake over and over again,” says Rob Jackson, a professor of Earth system science at Stanford who oversees Lebel’s work.

“Companies go bankrupt, and taxpayers pay the bills.” ![]() Not by mistake, by design.

Not by mistake, by design.![]()

Congressional efforts to create a well-plugging program for cleanup are stalled. Meanwhile, oil and gas companies have made trillions of dollars in profits over the past century and a half while enjoying relative impunity. On federal lands, where oil and gas companies actively drill, bond levels haven’t been adjusted for inflation since 1951, when they were set at $10,000 for a single well and $150,000 for however many wells a single operator controls nationwide. In California a company drilling 10,000 feet or more needs only $40,000. ![]() In Canada, there is zip requirement for bonds! We are incredibly stupid and pathetic here and have dirt for authorities and courts.

In Canada, there is zip requirement for bonds! We are incredibly stupid and pathetic here and have dirt for authorities and courts.![]()

Even spending all the billions of dollars required to plug the world’s millions of deserted wells won’t stave off environmental catastrophe. The vast heat and pressure of the Earth’s subsurface—the same forces that crushed dinosaur bones into hydrocarbons in the first place—mean that no plugging job lasts forever. Scientists and engineers debate how long cement can survive in the harsh environment of the Earth’s interior. Estimates typically fall from 50 to 100 years, a long enough time horizon that even some of today’s biggest oil and gas companies may no longer exist, but short enough to be uncomfortably within the realm of human comprehension. No regulations require states or federal agencies to measure emissions after wells are plugged.

While little is being done to prevent methane from creating catastrophic warming, less is being done to prevent water contamination. Researcher Kang, now an assistant professor of civil engineering at McGill University, worked as a groundwater monitoring consultant before getting her Ph.D. In 2016 she published a paper with Jackson showing that California’s Central Valley, where a quarter of the nation’s food is produced, has close to three times the volume of fresh groundwater as previously thought. Such good news came with an urgent caveat: Nineteen percent of the state’s wells came close to these aquifers. “It’s definitely a threat and something that needs protection,” Kang says. “There’s so much we don’t know.”

What we do know is scary enough. “The cement will deteriorate,” says Dominic DiGiulio, a senior research scientist for PSE Healthy Energy, an Oakland, Calif.-based public policy institute, who worked for the Environmental Protection Agency for more than three decades in subsurface hydrology. “It’s not going to last forever, or even for very long.” A.H.C. Church lies in the Solano Subbasin, part of the Sacramento Valley Groundwater Basin. Almost 30% of the region’s water comes from subsurface sources, according to a 2017 report from the Northern California Water Association. “Given sustained droughts, groundwater resources are going to be very important in the coming decades,” DiGiulio says. “California is going to need these resources.”

Among the hundreds of pages of records chronicling the well’s spud, activity, and plugging, the one consistent name was Bernard Church. One afternoon this summer, I called the phone number listed on the most recent document, from a 2004 inspection, and reached his wife, Beverly Church. She now lives in Walnut Creek, Calif., about 40 miles southwest of the well site, and she told me her husband had died nine years earlier.

He and their family never became rich. Holders of mineral rights can lease them back to oil and gas companies and receive royalties on what their wells produce. But because so little had been pumped from Church, none of the 20 or so family members who eventually held a stake wound up with much. “We didn’t make any money off of it,” Beverly says.

That’s not an uncommon outcome, explains Kassie Siegel, director of the Climate Law Institute at the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity. “Every once in a while someone might” get rich, she says. “But it’s not a thing. Big Oil is getting rich. For individual, ordinary people, it’s all risk and no reward.”

Refer also to:

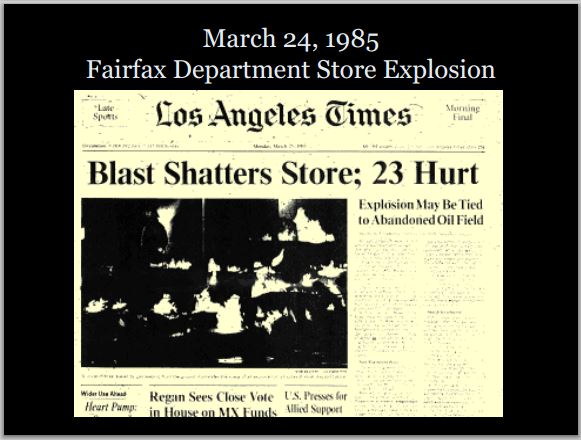

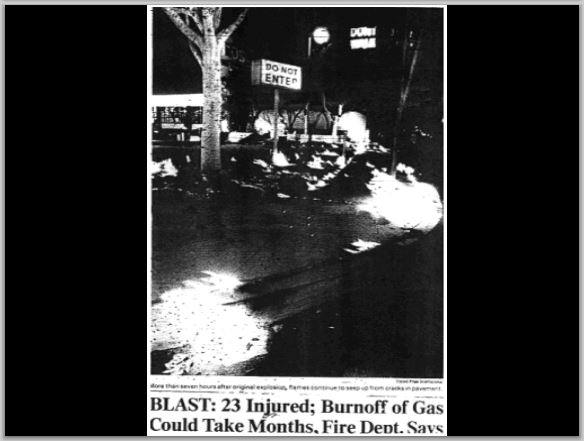

1985:

What did the authorities and “experts” do in response? Blame nature so as the protect the murderous polluters, copied the world over.

1995/96:

Report on the 2002 workshop on Groundwater Quality Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Winnipeg, Manitoba. Linking Water Science to Policy Workshop Series. Report No.2, 52 pages. Crowe, A.S., K.A. Schaefer, A. Kohut, S.G. Shikaze, C.J. Ptacek. 2003

Given that little is known about the long-term integrity of concrete seals and steel casings in 600,000 abandoned hydrocarbon wells in Canada, the study stated that the oil and gas industry’s future impact on groundwater could be immense. The report concluded that unconventional natural gas drilling such as coalbed methane (CBM) poses a real threat to groundwater quality and quantity, and that the nation needs “baseline hydrogeological investigations…to be able to recognize and track groundwater contaminants.”

Slides from Ernst presentations

2005: Cartoon in Calgary Herald:

2006: Bruce Jack Private water well explosion at Spirit River, Alberta Two industry gas-in-water testers seriously injured, also hospitalized when the methane and ethane contaminated water well ignited on testing day:

2006 My methane and ethane contaminated water, after Encana/Ovintiv illegally frac’d the aquifers that supply my community:

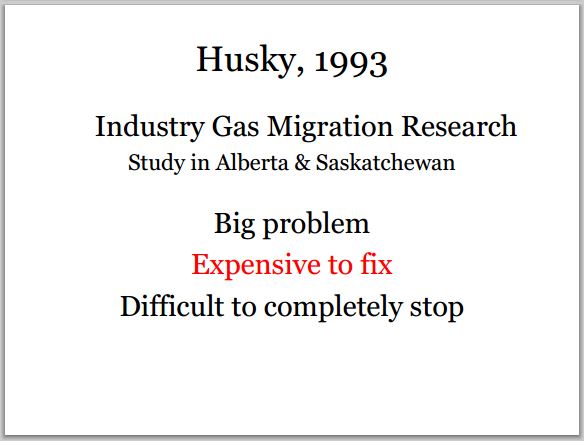

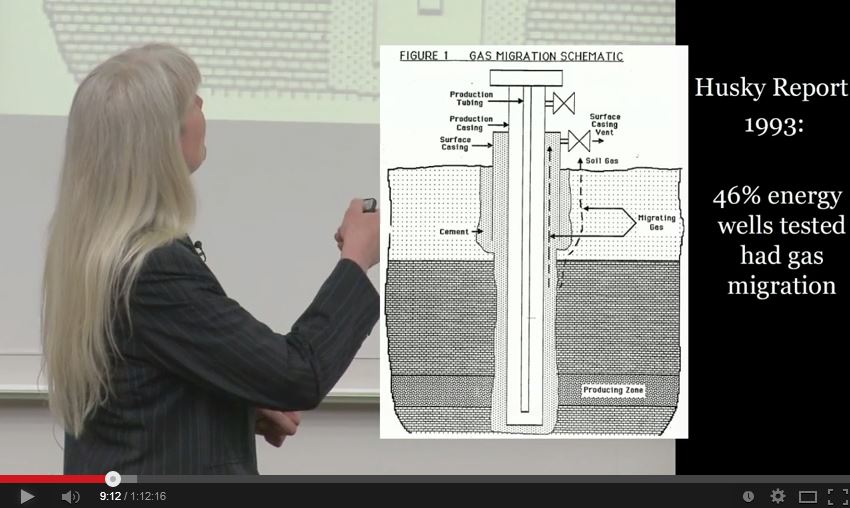

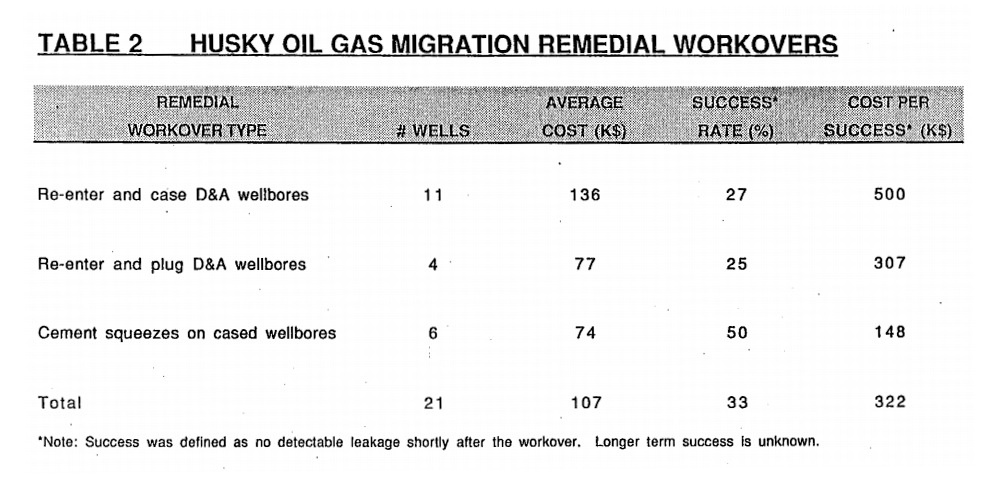

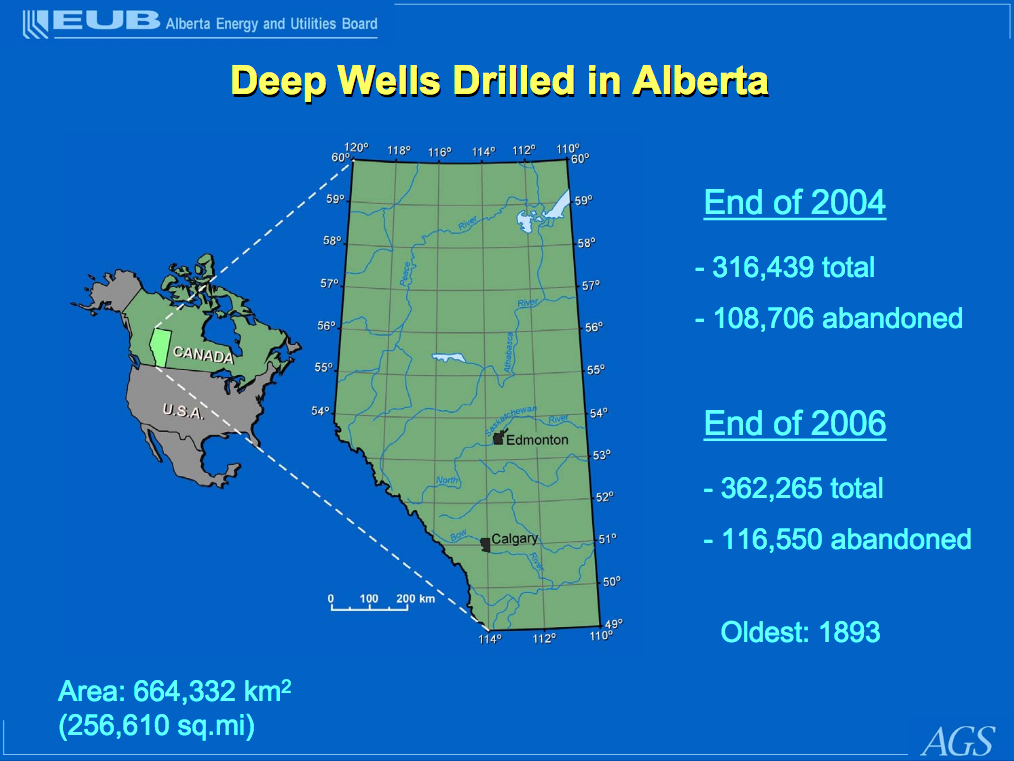

2007: Regulator report: Factors Affecting or Indicating Potential Wellbore Leakage

About 15% of vertical and 60% of deviated wells reported leaking.

As of end 2006, already way back then, 116,550 abandoned wells in Alberta.

2012: More Than Three Months Later, Methane Gas Is Still Leaking In Bradford County

In Tioga County:

2014: Fracking Wells Abandoned in Boom/Bust Cycle. Who Will Pay to Cap Them? Wyoming “May” Act to Plug Abandoned Wells as Boom Ends Only the people will pay, lawyers make sure of it.

2014: Action needed on abandoned energy wells leaking methane in Quebec Action needed everywhere but because it’s oil and gas industry pollution, action never comes.

2014: Ohio Energy Regulator Blaming Nature on First Day of Fatal Home Explosion Investigation, “these pockets are naturally occurring and not the result of human interaction, such as hydraulic fracturing or other gas wells” As “regulators” do everywhere, blame nature, or change history (like fact-fabricator Supreme Court of Canada judge, Rosalie Abella, ruling AER found me to be a vexatious litigant – to smear me and my public interest case – when documented evidence shows the “regulator” judged me to be a criminal then, 7 years later, a terrorist) or if not nature, blame the harmed.

The couple’s terrified dog haunts me still.

2016: Danger Below? New Properties Hide Abandoned Oil And Gas Wells

2016: Colorado regulators find leaking methane and VOC violations at 10 companies, Encana included

2016: In the Birthplace of U.S. Oil, Methane Gas Is Leaking Everywhere

But but but, CAPP ‘n companies promise us it’s all perfectly safe and “natural.”

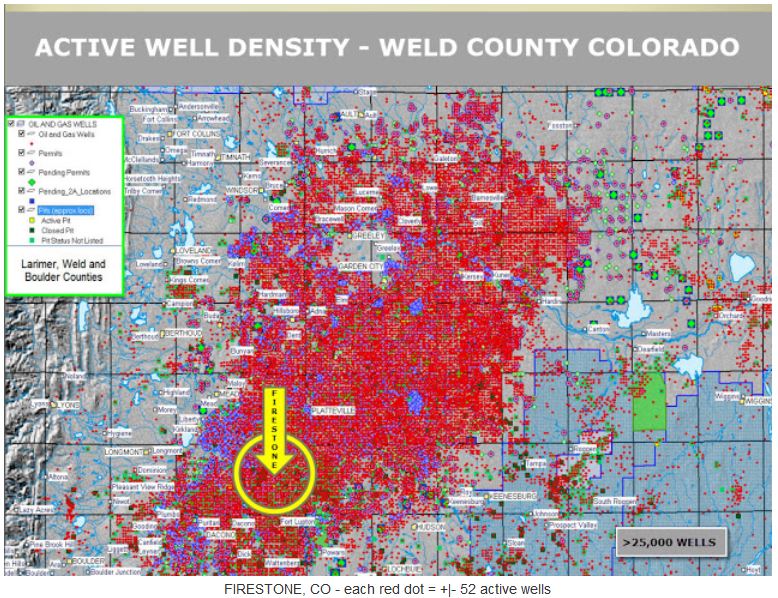

2017: Weld County Colorado offering explosive gas detectors to residents for free

2020: AER skulduggery escalates: Dave Goldie, Encana & Cenovus VP is new Chair (first was Encana & Cenovus VP Gerry Protti); Martin Foy, Encana crime-enabler, appointed Exec VP (remember AER exec VP, ex-Encana lying manager Mark Taylor?); Propagandizing Synergy Queen, Tracey McCrimmon & Encana crime-enabler Bev Yee appointed to the Board; Anti-science climate change denier, Steve Harper’s best buddy/compaign manager, Kenney’s Kamikazi campaign manager, John Weissenberger, made VP Technical Science & External Innovation Branch. Think anyone or our environment in Alberta will get “regulation” with a dirty oil patch gang like this commanding the sinking ship?