Nasty! In 1988, Alberta’s energy regulator, then ERCB (later became EUB; back to ERCB after EUB was caught breaking the law, lying and spying on innocent Albertans; now AER) and reporter Mark Lowey did not publicly report that Stoney is riddled with industry’s sour gas and processing (including by Pan Canadian, that became Encana and is now Ovintiv), and had been for about 10 years before the sour gas contaminated drinking water complaints began in 1981.

Why did AER, already back in 1988, blame nature, and if not nature, then bacteria, without any investigation or testing?

Same fake news spewed 15 years later by Darin Barter when AER was EUB (he later moved up to the National Energy Board). He too was reported blaming nature/bacteria in a newspaper (without the regulator doing any investigating or testing, not even after a municipal water tower blew up seriously injuring a water manager) for the life-threatening levels of gas found in Rosebud’s drinking water supply after Encana/Ovintiv illegally repeatedly frac’d the community’s drinking water aquifers.![]()

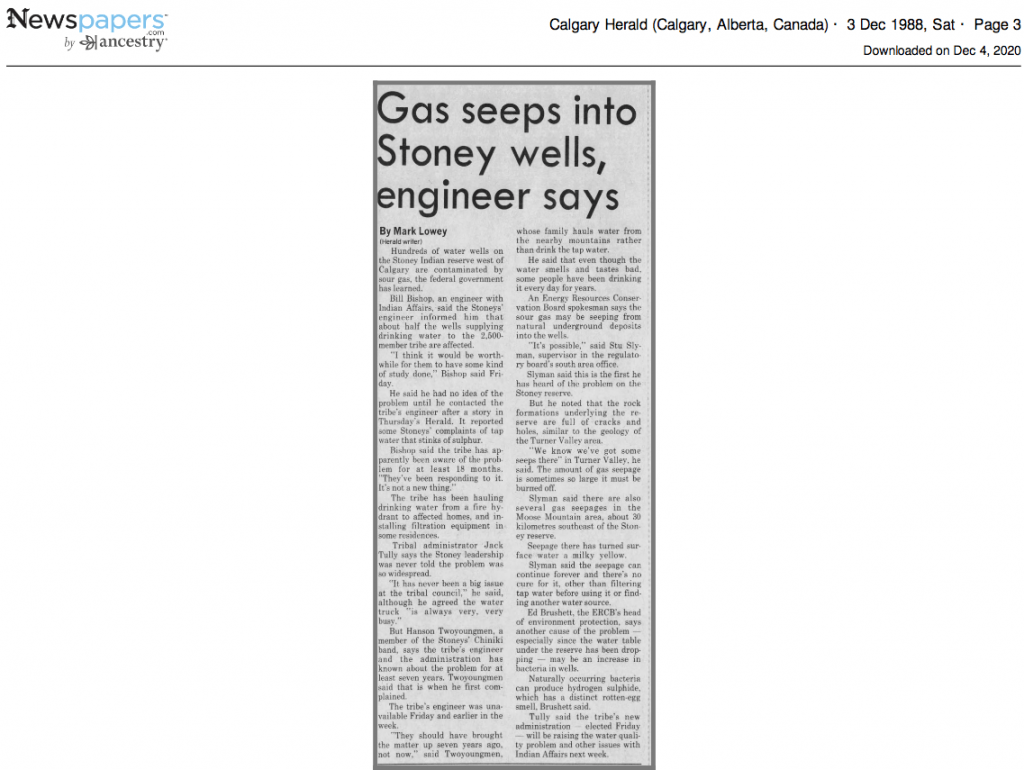

Gas seeps into Stoney wells, engineer says by Mark Lowey, Dec 3, 1988, Calgary Herald

Hundreds of water wells on the Stoney Indian reserve west of Calgary are contaminated by sour gas, the federal government has learned.

Bill Bishop, as engineer with Indian Affairs, said the Stoney’s engineer informed him that about half the wells supplying drinking water to the 2,500-member tribe are affected.

“I think it would be worthwhile for them to have some kind of study done,” Bishop said Friday. He said he had no idea of the problem until he contacted the tribe’s engineer after a story in Thursday’s Hearld. It reported some Stoneys’ complaints of tap water that stinks of sulphur.

Bishop said the tribe has apparently been aware of the problem for a least 18 months. “They’ve been responding to it, it’s not a new thing.”

The tribe has been hauling drinking water water from a fire hydrant to affected houses, and installing filtration equipment in some residences.

Tribal administrator Jack Tully said the Stoney leadership was never told the problem was so widespread.

… But Hanson Twoyoungmen, a member of the Stoney’s Chiniki band, says the tribe’s engineer and the administration has known about the problem for at least seven years. Twoyoungmen said that is why he first complained.

… An [ERCB] spokesman says the sour gas may be seeping from natural underground deposits into the wells. “It’s possible,” said Stu Slyman, supervisor in the regulatory board’s south area office.

… Slyman said the seepage can continue forever and there’s no cure for it, other than filtering tap water before using it or finding another water source.

Ed Brushett, the ERCB’s head of environment protection, says another cause of the problem … may be an increase in bacteria in wells. Naturally occurring bacteria can produce hydrogen sulphide which has a distinct rotten-egg smell, Brushett said. …

Using the Chemical and Isotopic Characteristics of Drinking Water to Determine Sources of Potable Water and Subsurface Gedogic Controls on Water Chemistry, Stoney Indian Reserve, Morley, AB. by Lynn Margaret McFarland, A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, Dept Geology and Geophysics Calgary, Alberta, 1997, National Library of Canada

Abstract

Subalpine regions are defined as cool upland slopes below the timber line, characterised by the dominance of evergreen trees. This thesis considers the following questions for a subalpine watershed on the Stoney Indian Reservation, using water chemistry and isotopes:

1. Can the chemistry and isotope analysis of the water be used to characterise the nature of the subsurface geology?

2. Does the aquifer geology control the quality of drinking water on the reserve?

3. Is it possible to separate the different aquifers the water comes from on the basis of their chemical and isotopic characteristics?

The deeper shale and sandstones have higher total dissolved solids concentrations and greater ion variability than the water from gravels, which closely resemble surface waters. Isotopes indicate that evaporative processes dominate the waters, water-rock interactions are occurring and that there is little bacterial sulfate reduction occurring.

All reserve waters met government drinking wafer guidelines. ![]() Rape & pillage Canada does not include natural gas, methane, ethane, propane, butane, pentane, sour gas under national drinking water guidelines, I expect to enable the ferocious, wide-spread gas contamination of drinking water wells by the oil and gas industry across the country.

Rape & pillage Canada does not include natural gas, methane, ethane, propane, butane, pentane, sour gas under national drinking water guidelines, I expect to enable the ferocious, wide-spread gas contamination of drinking water wells by the oil and gas industry across the country.![]()

… Differentiation of sulfur from a number of sources was undertaken by Van Donkelaar et al. (1995) to determine the relative amounts of sulfur coming from a localised source of sulfur, a sour gas processing plant. …

Introduction

Water quality standards published by the Government of Canada are used as a comparison to determine if the concentrations of various ions in the Morley water samples exceed the levels recommended for chemical and bacterial drinking water quality. These standards are used to determine if the waters are safe to drink. There ate two main categories of water quality determinations of concern for this study: firstly, chemical parameters that examine the dissolved components of the water and secondly, water bacteria levels. …

Consideration of the isotopic data illustrates that the surface and groundwaters are closely related and all are affected by evaporation.

None of the waters appear to have been strongly influenced by the bacterial reduction of sulfate….

Discussion and Conclusion

…

Both sulfur and carbon isotopes show poor correlation to nutrient levels which suggested that the bacterial activity in the waters was not a major control on the water composition.

Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, No 010, 2nd Session, 40th Parliament, Evidence, March 12, 2009

…

Mr. John Snow: We are located 45 miles west of the city of Calgary, in the foothills, and the main reserve that we are located in is Morley, Alberta. We also have two other reserves, the Bighorn Indian Reserve in the area of Rocky Mountain House, as well as the Eden Valley Indian Reserve in the Turner Valley area. So we have three reserves. We’re the only first nation having three reserves traversing the eastern slopes of the Rockies. It’s about 150 miles between each reserve, so we’re interspersed. We are the only first nation like that in the country. Thank you, Mr. Chair.

Mr. Marc Lemay: When oil was discovered there, the reserves were already established. So oil was discovered on your aboriginal lands. At first, did you take part not only in the discovery, of course, but more particularly in the harvesting of that resource?

Mr. John Snow: Mr. Chairman, thank you for the questions. Some of the first wells were discovered in that area in 1928, preceding any type of regulator or institution.

So we were not involved yet, even though there were activities happening on our lands. If you go today to the IOGC, you will see some pictures on their wall from 1928. Those are actual drilling rigs from 1928 that were drilled on Stoney lands.

Apart from that, and to follow up with supplementary point on your question, yes, oil was discovered in Turner Valley. It was not regulated properly. In fact it was burned off and wasted. There is a fire there that has never been put out, but still goes on. They call it “hell’s half acre”, and it’s part of the history of Turner Valley right now. We’re not far from there. So activities occurred without our involvement and, in many instances, there was much wastage. That’s a bit of the history.

Mr. Marc Lemay: For how many years have your communities been consulted on oil and gas exploitation on your reserves, on your ancestral lands?

Mr. John Snow: I can answer that in a general way, Mr. Chairman. Our communities were initially approached when the activity began in Morley, and that would have been in the late sixties, or 1968-69. At that time, they had created a group called Indian Minerals West, which eventually became Indian Oil and Gas Canada. So the consultations began formally with producing first nations like the Stoneys in and around the late sixties and early seventies. …

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS OF INTEREST TO OIL AND GAS LAWYERS by Mungo Hardwicke-Brown, R. Ben Rogers, Sandy McLeod and Chris Orr, March 17, 2017, Alberta Law Review

…

STONEY TRIBAL COUNCIL V. PANCANADIAN PETROLEUM LTD.

1. FACTS

This dispute involved the determination of royalties to be paid by the appellant PanCanadian Petroleum Ltd. (“PanCanadian”) to the Stoney Tribal Council (“Band”) pursuant to four mineral leases. PanCanadian had been deducting “TOPGAS” financing charges as well as operating, marketing and administration charges (“OMAC”) when determining the selling price of the gas. This selling price was the price which PanCanadian then used to calculate royalties payable to the Band. …

The applicable regulations, the Indian Oil and Gas Regulations, were originally made in 1977 and amended in 1981 pursuant to the Indian Oil and Gas Act and its predecessors. Those regulations establish how the royalty is to be calculated. …

The Band brought their claim on the ground that the TOPGAS financing charges and the OMAC charges did not apply to the calculation of the royalties on Indian lands, thus entitling them to an accounting and judgment for the amount of the unauthorized deductions.

The Court of Queen’s Bench decision of McIntyre J., dated April 9, 1998, found that the Band was entitled to a recalculation of royalties without deduction of OMAC and TOPGAS financing charges and repayment from May 3, 1983.

The issues on appeal were:

Is the applicable limitation six years or ten years?

Were the TOPGAS and OMAC charges properly considered in computing the royalties?

2. DECISION

a. Limitation Period

Section l(e) of the then Limitation of Actions Act91 defines “land” as including an interest in land. The trial judge had held that a royalty was an interest in land and, as such, it was subject to s. l 8(a) of the LAA, which sets ten years as the limitation for “proceedings to recover land.”

It is important to note that the Court of Appeal chose not to deal specifically with the question of whether a royalty was an interest in land. The Court looked at the amended statement of claim of the Band and determined that the relief claimed by the Band was for an accounting and judgment in the sum of all royalty monies due to the Band by reason of unauthorized deductions or, alternatively, an accounting for all part payments received by the Band from the gas buyers relating to contracts to market or sell gas obtained from the reserved lands and judgment for the royalty portion of such part payments. The Court held that the first basis for the claim was in contract, not a claim seeking to recover the royalty itself ( and thus was not a claim to recover an interest in land). The other causes pleaded in the claim were breach of trust, breach of fiduciary duty and unjust enrichment. None of these could be regarded as an action to recover an interest in land.

In this case, the natural gas to which the royalty interest attached was lawfully severed and sold in accordance with oil and gas leases. The Band was not seeking to recover their royalty interest in kind. Any property interest had been alienated and what remained was not an action for the gas, but for the correct sum of money owing under contract. The limitation period, therefore, was found to be six years.

b. Deduction of Charges

The question on this issue was whether the Take-or-pay Costs Sharing Act, and the deductions it permits, apply when calculating the royalties on gas produced from reserve lands. PanCanadian argued that the royalty was calculated in accordance with the IOGR because it was based on the sale price. It argued that the sale price was the actual price at which the gas was sold. The Court of Appeal, however, found that the TPCSA describes the charge as a “levy” that is payable on delivery of gas and that the person liable for the payment is the seller. The TPCSA does not purport to be setting the selling price or to be part of the calculation of the selling price of gas. By the terms employed in TPCSA the levy is an added charge on the seller. In practice the buyer would pay PanCanadian after deducting the TOPGAS and the OMAC charges; however, technically these charges were a separate obligation, not part of the selling price of gas. The Court found that such charges were not permitted under the legislation regulating oil and gas production on reserve lands and they should not have been deducted before calculating the royalties owed to the Band.

The Court of Appeal found that the Band was entitled to a recalculation of its royalties without the TOPGAS and OMAC charges; however, their claim was limited to six years.

Refer also to:

Industry and regulators have known for decades that the oil and gas industry sours sweet formations. What do our authorities do? Deregulate & lie to enable it.

Sour Gas damages the brain, even at very low levels:

1. Exposure to levels below 10 ppm permanently damage the human brain

2. Harm from levels below 10 ppm by Worksafe Alberta

3. Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) LOW LEVEL HEALTH HARM WARNINGS:

Sour Gas Concentration (ppm)

Symptoms/Effects

0.01-1.5

Odor threshold (when rotten egg smell is first noticeable to some). …

2-5

Prolonged exposure may cause nausea, tearing of the eyes, headaches or loss of sleep. Airway problems (bronchial constriction) in some asthma patients.