2020: How Militarizing Police Sets up Protesters as ‘the Enemy,’ A scholar and former officer traces the trend. It’s been building in Canada and the US for years by Tom Nolan (visiting associate professor of sociology at Emmanuel College Boston)

The increasing militarization of police is happening in Canada, too. Photo of heavily armed RCMP in Wet’suwet’en territory, January 2019. Photo by Michael Toledano.

***

Company behind Minnesota’s harmful pipeline project is allegedly paying cops to harass Native women by Aysha Qamar, April 6, 2021, Daily Kos

As the fight against the Enbridge Line 3 replacement project continues, new information including invoices have raised concern over the relationship between Minnesota police officials and the company leading the project. The pipeline expansion project is being led by Enbridge, a Canadian pipeline company responsible for the largest inland oil spill in the country. Once completed, the project will go through untouched wetlands and the treaty territory of Anishinaabe peoples, Daily Kos reported.

Activists at the frontlines of the movement have noted not only excessive “safety patrols” of the area, but particular policing of female Indigenous women protesting the pipeline. While invoices obtained by HEATED do not show evidence of Enbridge paying the police department to spend time intimidating and harassing protesters, it does indicate that within the last two months the Cass County Sheriff’s Department has increased its reliance on Enbridge to fund its officers’ paychecks.

According to the Stop Line 3 campaign, Line 3 is a pipeline expansion project that will bring almost one million barrels of tar sands per day from Canada across Minnesota to Wisconsin. “All pipelines spill. Line 3 isn’t about safe transportation of a necessary product, it’s about expansion of a dying tar sands industry,” the campaign argued.

Since the project’s announcement in 2014, activists including the Ojibwe Water Protectors, have been calling for officials to halt the project because not only does it violate Indigenous treaty rights but it poses a huge risk of pollution to the environment.

Construction began on Dec. 1, 2020, and was said to be 50% completed by March 11, according to an announcement by Enbridge. Segments in Canada, North Dakota, and Wisconsin were completed prior to this announcement. Since then protests have been occurring almost daily with activists and advocates, mainly those who identify as women, facing arrests. More than 130 people have been arrested in connection to Line 3 protests, CNN reported. Additionally, over a dozen were arrested on March 25 alone.

Those not arrested have been facing intimidation and harassment at the hands of the police, who are also allegedly tracking protesters. This raises concerns of the influence Enbridge has on the local police department, as invoices indicate the company has been paying for the department’s salaries.

According to invoices obtained by HEATED, Minnesota law enforcement officials and Enbridge began their relationship last year when the company had its permit for Line 3 approved. According to HEATED, the permit noted that Enbridge must pay police for any pipeline-related public safety activity, in efforts to avoid putting undue burden on local taxpayers.

As a result, the Cass County Sheriff’s Department is currently seeking at least $352,576.22 in reimbursement from Enbridge for hours and equipment related to “Line 3 Project Security.”

According to the invoices, the request spans from November 28 to February 19. While most of it is related to physical security hours worked, some of it accounts for equipment including a Live Scan Fingerprint System, which allows officers to quickly confirm the identity of the people they arrest.

Prior to January, less officers were present at the site. Between January to February 19, 43 officers were logged to have been patrolling the pipeline project to prevent disruption, HEATED reported. Records, compiled by HEATED, indicate that if each officer worked full-time, between January to February, the average Cass County officer spent at least 17% of their regular working day on Line 3 “Safety Patrol,” in addition to about 12 overtime hours a week.

What’s worse is that Enbridge is not only paying Cass County officials, the Canadian company has even tapped into other counties for its “safety patrol.” At this time it is unclear how many counties and how much influence Enbridge has over the local police departments, in addition to what HEATED has found.

While it is normal for police officials to be present at certain projects to protect the construction, the actions these officials are taking under the the guise of “safety patrol” have been troubling. Activists are living in fear due to harassment and intimidation at the hands of the police, especially women.

Even prominent actress and activist Jane Fonda expressed concerns over police patrol after visiting the project site. “We pulled over to wait for them, it took a long time to process their identification, and they ended up not being ticketed,” she told HEATED. “Then we drove 12 miles to the press conference and the police car followed us the whole way.”

This fear is not new and restricted to Fonda’s experience. According to tribal attorney and activist Tara Houska, anyone working to oppose the Line 3 project has been followed by cops while driving alone. While many have been verbally intimidated, some have reported violence and brutality. “The police presence has been strong,” Houska told HEATED.“We’ve seen groups of squad cars 20-plus strong from different counties guarding the line. Last week a car followed us for two hours straight.”

In March Houska also told CNN that while some advocates were physically arrested at construction sites, police also watched social media feeds to identify others and sent a summons in the mail. “They seem to think that it’s going to deter us from protecting the land. They are fundamentally missing the point of what water protectors are doing, which is willing to put ourselves, our freedom, our bodies, our personal comfort on the line for something greater than ourselves,” Houska said.

Women have been not only wrestled to the ground by male officers but held overnight in jail cells meant for lesser capacity, making social distancing impossible. According to HEATED, even female journalists have faced abuse by cops with some being removed from projects with editors fearing for their safety. “I don’t feel safe,” one woman told HEATED. “I walk by the officers in the grocery story every day knowing they’re preparing to beat me up—and doing it with the help of Enbridge.” ![]() Worse, enabled by our white male-dominated politicians and courts

Worse, enabled by our white male-dominated politicians and courts![]()

Enbridge’s Line 3 pipeline will not only violate treaties protecting Indigenous land and water but endangers lakes, rivers, and wild rice with the barrels of tar sand oils it hopes to transfer. Enbridge knows what risks its project brings—we cannot stay silent as it works to pay off law enforcement officials and intimidates those who stand up against its harmful pipeline.

A few of the comments:

koNko:

Corporate capture of local government is increasingly a means of denying justice.

This does not surprise me at all.

polliwonk:

Make that foreign corporate capture. Should be illegal in some way.

Tor:

This kind of thing should be banned. How is it that a private company can turn a government agency into its private security company merely by paying some money. I don’t think I could pay the local cop shop to provide extra security patrols for my house. How is this different?

IdleMindness:

Unfortunately, in many states and counties, County Police can be hired to provide “security” for private events, such as church functions, and as we see here, for oil pipeline “project protection”.

Obviously, when a non-for profit/non taxed, or private company is allowed to hire publicly funded police agencies, there is now a gray area as to who’s interests are being policed? On the surface, one would expect that a County Police hired to provide protection for a private project or event, would do their policing according to their already existing public rules or enforcement and engagement, and also be bound to existing local, state, and federal laws and requirements.

That would be the “obvious”, and that’s where the problems are. If that oil company hires a public police agency to provide private security, and the wants of that oil company are largely known in the community, then the how, when, who, and why the county police are securing doesn’t, and mostly isn’t, actually penned for all to see.

This type of hiring can easily be lead by a mob boss like public communication to the privately hired public policing agency. It can go something like this,

“Yes, we need to have your officers keep our project/s secure from anyone who is opposed to our project and our company. We’re hiring you to make sure that we have “legal” protection of our projects from anyone who may not like and/or try to stop our project from continuing peacefully, so that we can provide positive outcomes to the community and everyone involved. We would like for you and your officers to ensure that our project is secured from anyone who may not agree with our legal right to do our project. Please do your best and do what you need to do according to your rules and the law to help us to secure out project, and that it goes well.”

Sounds all legit and innocent, right? Yeah, and everyone is supposed to believe that their public police agencies, hired for private security, will abide the law and not the wants of the private company hiring them and paying the officers more than their regular salaries would get them. Typically, when county police are hired for private events or projects, the officers doing the work are NOT supposed to be on public time. The officers doing the extra work are to do this extra security work as a “side” job, where the extra hours of work are being paid by the private company paying for the security.

Snarcapuss says:

What could ever, or has, gone wrong with such a clearly legit and innocent practice? All public police are always there to protect the public first and foremost…right? After all, it is the public that pays for that police protection….ahhh…wait… Who’s paying for that security again, security AGAINST the public who are being negatively affected by the private project, and the operators of that private project just hired the “public” police to provide private security, AGAINST that public? Hmmm…….

FishOutofWater:

Emily Atkin literally has the receipts. You can remove the legalese crap word “allegedly” from your title.

We don’t need tar sands and the dangerous diluted bitumen “dilbit” that Enbridge sends through its pipelines. Dilbit is a far greater hazard to water because it is a toxic tarry product diluted in by organic solvents. The solvents evaporate and the toxic goo remains. It’s dangerously toxic and very hard to clean up.

Liberal in a Red State:

Biden needs to do whatever he can to block this pipeline ASAP.

Ethrid:

WTF is going on with the Minnesota police?

Ethrid:

I do not understand why people are so ready and willing to take a giant dump in the middle of the country for CANADIAN oil I thought people wanted to put America first

Word Mix:

This pipeline is very unpopular in Minnesota. Our public agencies are corrupt.

Carlsbad Dave:

Tar sands require more energy to extract the oil from the sand than it produces in the end. It’s incredibly stupid to do that!

High Iron:

There is no pipeline that won’t leak. The welders are most likely non union and not pipe certified. there is no inspection of welds. that’s where the leaks come from. The high pressure needed to pump this thick crap through the pipeline is what causes the pipeline to seep through the bad welds and leak into the environment.

Stormfrost:

We The People MUST demand that Tribal Lands are sacrosanct. Entrance onto or ANY usage of Tribal Lands can ONLY happen with the approval of the Tribe OWNING the land. Local, State and Federal Laws NEED to support Tribal Ownership ONLY and even imminent domain laws must go to the Supreme Court.

Gilligansplace:

This really ticks me off on so many levels. First, I always thought Canada had a fair relationship with their own First People. ![]() Canada treats non whites, notably Indigenous, horridly, and our police are dreadful abusers of women to benefit polluting oil and gas companies, including abusing white women if they speak out. Canada is more sneaky about it than USA. We hide the abuses under a guise of being “nice” and saying sorry, often, while the abuse continues.

Canada treats non whites, notably Indigenous, horridly, and our police are dreadful abusers of women to benefit polluting oil and gas companies, including abusing white women if they speak out. Canada is more sneaky about it than USA. We hide the abuses under a guise of being “nice” and saying sorry, often, while the abuse continues.![]() So now they are going to disrupt OUR indigenous people- with our governments blessings? I wonder how much and who got all of that $$! And then there is our own BIA who were supposed to help and protect the Indigenous communities and the treaties in the US. No matter what party is in the WH/Senate/Congress the BIA seems to always kowtow to the government, never who and what they were meant to protect. Honestly, I am so sick of being white– and yet if I wasn’t I couldn’t do anything to help in situations like this. Perhaps if we added into the school history books the ‘real’ history of nations there would be less prejudice. One more example of White Supremacy!

So now they are going to disrupt OUR indigenous people- with our governments blessings? I wonder how much and who got all of that $$! And then there is our own BIA who were supposed to help and protect the Indigenous communities and the treaties in the US. No matter what party is in the WH/Senate/Congress the BIA seems to always kowtow to the government, never who and what they were meant to protect. Honestly, I am so sick of being white– and yet if I wasn’t I couldn’t do anything to help in situations like this. Perhaps if we added into the school history books the ‘real’ history of nations there would be less prejudice. One more example of White Supremacy!

mnLib:

What ever gave you the idea the Canada had a fair relationship with its First Nations peoples?

There has been significant improvement over the past 20 years in Canada’s recognition of First Nations’ rights and attempts to redress past wrongs.

However, First Nations communities in Canada still suffer way higher rates of suicide, unemployment, substance abuse, violent crime, poverty and lack of resources than non-native communities. Some of this is due to First Nations communities being located in isolated areas, particularly in the north but a lot has to do with decades of underinvestment and neglect as well as exploitation of resources by forestry, and mining concerns without adequate recompense to the First Nations who claim those lands. The residential schools atrocity is a particular low point in Canadian history as a concerted effort to destroy First Nations language and culture and an environment that fostered physical and sexual abuse of children that left lasting scars on entire communities.

It’s getting better but the relationship between Canada and First Nations in Canada has not been that much better than that of USA with respect to indigenous people historically.

mnLib:

However, to be fair, it’s not “Canada” that’s doing this. It’s Enbridge, a Canadian based international corporation.![]() Yes, but, Canadian authorities, including many racist politicians and courts, enable it.

Yes, but, Canadian authorities, including many racist politicians and courts, enable it.![]()

Driver324:

It’s time to revoke all permits and stop then dismantle the Line 3 pipeline. Then, maybe we should require the police in certain areas of Minnesota to cycle back through training and lay off any who don’t respond positively. The police, largely supported by conservatives but usually paid from tax revenues, are becoming a liability, not an asset.

CAinPA:

There will be a spill…then watch them cover their asses….while virgin lands are soaked with filth, never to be clean again, not in a hundred lifetimes, so many species of wildlife wiped out, land destroyed…and for what? FOR WHAT?? Sometimes it is better to be old, to know you may not be alive to watch that black filth destroy more and more of the only greatness this country really has. But hey, the investors will be on their yachts, far out on the turquoise sea, toasting their brilliance, their coup…

Kootenay Coyote:

Corporate harm to Indigenous people is a rank, festering, stinking evil. This is consistent with other bad behaviours, including hiring mercenaries to spy on & attack Indigenous protesters.

Kick the Fracking Industry Out of Indian Country, For decades, the federal government has helped the extractive industry exploit Indigenous lands. Instead, it could support tribes that want to say “no.” by Nick Martin, April 6, 2021, The New Republic

On Sunday, The Guardian published a comprehensive report on the environmental, health, and legal issues raised by fracking in the Eastern Agency of the Navajo Nation. In particular, the outlet highlighted instances in which fracking wells owned by Denver-based gas and oil company Enduring Resources had either exploded or malfunctioned, contaminating nearby water sources. In one case from 2019, a fracking well leak brought on by a valve failure pushed 1,400 barrels of slurry off the well pad and into the surrounding snow; by the time the company moved to contain the contaminated area, the snow had melted and the toxins had been washed downstream into the adjacent creek bed. Three days later, an explosion sounded off from another nearby well. Three months later, at another site in the area, 20 barrels of crude oil were sent straight into the earth.

Speaking with The Guardian, Navajo Nation Council officials Mario Atencio and Daniel Tso made the case that all of these spills and the health risks to those living near them (including Atencio’s grandmother) were the result of both well-calculated corporate greed and federal apathy. And looking beyond the Eastern Agency and the Navajo Nation to the whole of Indian Country, it’s hard to disagree with their assessment.

The Guardian’s report comes at a pivotal moment for U.S. fracking policy, as well as Indigenous-federal relations. Since the shale boom of 2009, and for decades before it, the northwest corner of New Mexico, like many other areas in both Indian Country and America, has been transformed into a maze of pipes and well pads. That these operations are densely packed onto the lands of sovereign tribal nations is no accident; it’s part of a much broader trend by extractive outfits, which see rural tribal lands as short-term cash cows and for decades have been mining, fracking, and developing the resources that these communities have stewarded and depended on for millennia. And it’s all been made possible by the governmental entities purportedly tasked with safeguarding the lands for the tribal nations.

Fully understanding why natural gas efforts have focused on this particular New Mexico pocket of Navajo Nation, as opposed to its lands in Arizona—where efforts are more highly concentrated on the lands of the San Carlos Apache and White Mountain Apache tribes—requires a knowledge of trust and fee land statuses and how they’re managed by the individual owners, tribes, and federal government. Many of the lands under review by the Guardian report are known as off-reservation trust lands. This means, legally speaking, that they are not part of the Navajo reservation, where in some cases the process for obtaining a drilling permit is more stringent due to consultation and other regulatory requirements. But the land is still held in trust by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs for the Diné citizens who live there, and the BIA is tasked with keeping the residents informed regarding decisions about any potential contracting or sales involving the land.

In an area with a high unemployment and poverty rate, when gas and oil companies come knocking with contracts to set up fracking operations on people’s lands, saying no to the upfront cash is a tough sell. More often than not, Atencio pointed out, the oil companies come into the conversations fully lawyered up, while Diné citizens are left alone to make a decision that will affect their homelands for generations to come. As for the BIA, which is in charge of managing land rights for those on trust lands, Tso claimed the agency couldn’t be bothered to lift a finger in opposition to the companies. “Nobody from the BIA advised those folks,” Tso told The Guardian. “The BIA stood in the corner, stood in the shadows. Never said anything.”

We have covered this ground before at The New Republic. This is a familiar story not just about the natural gas industry, though its pipeline sales pitch is particularly ubiquitous across Indian Country. Destructive mining operations like Resolution Copper’s proposed mine on San Carlos Apache lands, much like those overseen by the coal and gas industries, dangle a dwindling number of jobs to communities impoverished by land dispossession and criminally underfunded social programs. They spend a half-century or so poisoning the land and waters, and just when the people have had enough, the companies flee, leaving behind devastating damage—like the underground chambers of phosphorous sludge that FMC Corp buried below the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes.

Any serious attempt to confront the sins of extractive industry also has to consider the federal actors who made this possible. While the Trump administration pushed through an astounding number of gas and oil leases in the final months of its term, the shale boom that drove so many of these companies and corporations to Indian Country happened during the Obama years. As for coal and other resource extraction on Native land, well, that has been a bipartisan effort for as long as America has existed.

So far, the Biden administration has trended toward progress on the matter of ensuring tribal communities are both heard and helped. One of the president’s opening executive actions included a pause on gas and oil leases on public lands, and the Interior Department—which houses both the BIA and the Bureau of Land Management (in charge of leasing public lands for development)—has already hosted a round of consultation sessions with tribal leaders. And what potentially makes this moment in time different from the Obama and Clinton administrations is the fact that the Interior is now led by an official who actually has a record of both combatting further reliance on fossil fuels and supporting Indigenous rights.

Secretary Deb Haaland, who herself hails from New Mexico as a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, is not even a month into her tenure as the head of the Interior, but so far, her department appears to be making good on her stated interest in rolling back drilling operations on public lands. At a virtual conference on the federal oil and gas program held in late March, Haaland said past extractive efforts have been “rushed” without any “careful consideration of the impacts to the environment and future generations of Americans.” She went on to defend the Biden administration’s temporary pause of gas and oil leases on public lands, saying it would allow the Interior to reexamine the federal fossil fuel programs.

Last week, in Haaland’s first television interview, conducted by CBS, she spoke of the way Indian Country has been taken advantage of by extractive interests, saying, “Often, it’s been easy to take land away to drill and mine in sacred places.” The temporary pause will, potentially, allow for her and other Cabinet heads to put in place new, more stringent regulations on how non-Native companies operate on tribal lands. (She has not publicly mentioned any specific changes yet, telling reporters last Friday only that “the American taxpayers deserve to have a return on their investment.”)

One of those solutions that the Biden administration has thus far not moved or signaled a move on is Free, Prior and Informed Consent. Whereas the current model requires only consultation (a box to be checked in most instances), FPIC would require the sign-off of the tribal nation’s government before any new developments proceeded—something that tribal leaders have pressed the Biden administration’s Interior about in its first few months in office. However, while tribes wait for the administration’s position on FPIC, Haaland has already made moves to create a Missing and Murdered Unit within the Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Justice Services, which will lead and coordinate cross-department and interagency work regarding missing and murdered Indigenous citizens—a crucial endeavor given the crisis coincides often with the transient workforces of extractive companies.

Following the line between wonky Interior policies like FPIC and the on-the-ground effects of fossil fuel extraction can be difficult. But doing so is crucial, because despite what industry stalwarts keep claiming, the consequences of extractive practices from mining to fracking remain a clear danger to communities now and for years to come. As I wrote ahead of Haaland’s confirmation, she will not leave this office having rid Indian Country of all the exploitative industry practices that companies have spent decades codifying into federal law. She even acknowledged this in broad terms when speaking with CBS, admitting that she knows “the fossil fuel industry will continue for years to come.” But Haaland is also on the record having recognized that if America is to properly steward its lands and waters, the federal government cannot continue helping the fossil fuel industry plunder its lands.

Haaland’s Interior now stands at an intersection unlike any faced by previous Interiors. Here we have a Native official in the federal government, from a fracking-heavy state, who throughout her career has made it clear that she has the ability to grasp the economic, cultural, and political forces that define these issues and still produce answers that center tribal sovereignty and the well-being of people and nature alike. There are Capitol and Indian Country politics that may well limit the progress this Interior can achieve. But having someone in charge who gets it—well, that’s a start.

‘No one explained’: fracking brings pollution, not wealth, to Navajo land, Navajo Nation members received ‘a pittance’ for access to their land. Then came the spills and fires by Jerry Redfern, April 4, 2021, The Guardian

It’s not clear why the water line broke on a Sunday in February 2019, but by the time someone noticed and stopped the leak, more than 1,400 barrels of fracking slurry mixed with crude oil had drained off the wellsite owned by Enduring Resources and into a snow-filled wash. From there, that slurry – nearly 59,000 gallons – flowed more than a mile downstream toward Chaco Culture national historical park before leaching into the stream bed over the next few days and disappearing from view.

The rolling, high-desert landscape where this happened is Navajo Nation off-reservation trust land, in rural Sandoval county, New Mexico. Neighbors are few and far between, and they didn’t notice the spill. The extra truck traffic of the cleanup work blended in with the oil and gas drilling operations along the dirt roads in that part of the county.

Then three days after the spill, something ignited and exploded 2,100 feet away on another wellsite owned by Enduring Resources, starting a fire that took local firefighters more than an hour to put out.

The two accidents account for just 1% of oil- and gas-related incidents in north-western New Mexico in 2019, according to statistics kept by the New Mexico oil conservation division (OCD). Since those two, there have been another 317 accidents in the region as of 29 March, including oil spills, fires, blowouts and gas releases.

There were 3,600 oil and gas spills over the previous decade, both smaller and larger.

In both cases in February 2019, the people living closest to the accident sites were among the last to know what happened. ![]() Same happened to the frac’d people living in Rosebud, Alberta. Encana knew, AER knew, Alberta Health knew and Alberta Environment knew, but not one authority warned the residents using water Encana had illegally frac’d, they did not even warn Wheatland County’s water manager, who later was seriously injured when the community’s concrete water reservoir blew up in an explosion caused by an apparent “accumulation of gases.” The authorities didn’t even tell us that Encana had broken the law, they were too busy covering it up and working to intimidate, shame, blame and silence the harmed.

Same happened to the frac’d people living in Rosebud, Alberta. Encana knew, AER knew, Alberta Health knew and Alberta Environment knew, but not one authority warned the residents using water Encana had illegally frac’d, they did not even warn Wheatland County’s water manager, who later was seriously injured when the community’s concrete water reservoir blew up in an explosion caused by an apparent “accumulation of gases.” The authorities didn’t even tell us that Encana had broken the law, they were too busy covering it up and working to intimidate, shame, blame and silence the harmed.![]()

Daniel Tso, chairman of the health, education and human services Committee of the Navajo Nation Council, chalks up the lack of communication to a prevailing attitude he sees among outsiders working on Native American lands: “Oh, it’s on Indian land. Don’t worry about it.” ![]() Same in Canada, where our authorities don’t give a damn about missing and murdered Indigenous women in oilfields – how many raped by oil workers and or police?

Same in Canada, where our authorities don’t give a damn about missing and murdered Indigenous women in oilfields – how many raped by oil workers and or police?![]()

Because, historically, few outsiders have.

… North of the highway is land called Dinétah, the center of the Navajo people’s creation story. The Navajo call themselves Diné, which means “the People”.

On the south side of the highway, a hand-painted sign reads “Entering Energy Sacrifice Zone” next to the turnoff to the spider web of muddy, snowy, rutted dirt roads that string together the homes and drilling rigs and wells in the area. It takes a vehicle with four-wheel drive to confidently navigate here. That’s what the oilfield workers drive, if they aren’t driving semis.

“It’s really hard to come here,” says Mario Atencio, a legislative district assistant with the Navajo Nation Council.

He’s talking of the emotional difficulty.

This land is infused with his people’s history, but with all of the wells, “it looks like a very industrial landscape”. His grandmother’s home is about a half-mile away from – and is the closest to – the two accident sites.

On maps, the area is defined by the rectangular grid of private lands, federal lands and Navajo Nation off-reservation trust lands, which are managed by the US Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) on behalf of the Navajo. This checkerboard is a land of often-differing jurisdictions, rules and interests. And, for decades now, oil and gas wells.

Local residents have complained for years that officials with the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and BIA haven’t listened to their concerns about drilling in the area. ![]() Same in Canada.

Same in Canada.![]()

The most recent wave of drilling started around 2009 when land agents called families to the Chapter house to sign leases for the oil beneath their homes. Tso says they were treated like football players and told, “Sign here, you’ll get a signing bonus.”

“They don’t tell us, you know, ‘There’s a big oil boom right here and you’re sitting on some riches so you better be sure you have your own lawyers at the negotiating table,’” says Atencio.

Many didn’t understand what they were signing and what the future would bring. “When you have more than 70% unemployment and you have more than 70% of the population living in abject poverty, you can’t fault them for signing,” Tso says.

He lays some of the blame for the misunderstanding at the feet of the Bureau of Land Management, which manages leasing rights. But the majority of blame lies with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, he says, which manages land rights on behalf of those living on Navajo trust lands.

“Nobody from the BIA advised those folks,” Tso says. At the meetings, “The BIA stood in the corner, stood in the shadows. Never said anything.”

Public affairs specialists from the BLM and BIA did not respond by deadline for this story.

Tso tells the story of an elderly woman who signed, thinking that the drilling for oil would be like a John Wayne movie: a man digs a hole in the ground, strikes oil and then dances in the fountain of black crude that shoots up – and everyone rakes in the money.

Tso says she told him: “But right now, I can’t even get a good night’s sleep because of the truck traffic.”

And because of an allotment system that divides ownership of tribal lands among all of the families and all of the people attached to a parcel, the money most people received was less than expected. Atencio explains that an allotment with 10 people on it might pay out $1,000 a month. But there are also allotments with hundreds of people. “It’s significant to some people,” he says, but “that’s a mere pittance for destroying the water, the air. And dumping hazardous waste. Tons of it.”

“Nobody explained this process to the folks who signed,” Tso says.

The People in Counselor say they weren’t counseled.

At first, nobody explained the February 2019 spill and fire to local people, either. Someone in Montana heard of the explosion and contacted Tso through the grapevine. Atencio received an email from someone with the Navajo Nation nearly two months after the spill. That was the first the two heard of the accidents and their severity.

Enduring Resources of Denver owns both wells and more than 920 others in New Mexico, all of them in the north-west corner of the state. The company did not respond to repeated calls for comment on this story, but incident reports filed by the company with OCD offer an outline of events. OCD regulates nearly all aspects of oil and gas production in the state: from permitting wells to tracking spills to tallying production to certifying closed wells.

According to the reports, a contractor initially spotted the 17 February spill. The well was new and had just been hydraulically fractured….

A fracking water hose runs through the desert and connects with a fracking operation on Navajo trust land north of Chaco Culture national park. Photograph: Jerry Redfern

At the end of that process and before producing a clean stream of oil or gas, a well produces “flowback”, a combination of fracking slurry mixed with oil, gas and the brine that often forms near petroleum deposits.

A valve failed on the well, causing an “integrity failure” on the flowback line, leading to 1,400 barrels of that contaminated slurry pouring off the well pad, across a dirt road and into the snow-filled wash. Workers built a small dam to contain the slurry so it could be recovered, but snowmelt washed almost all of it downstream. Workers built more check dams, but most of the slurry eventually soaked into the creek bed.

Three days later at the neighboring well – also newly fracked – a tank holding flowback caught fire after someone didn’t properly ground a vacuum truck on an adjacent tank. That created a static buildup that sparked and ignited fumes from the flowback.

“I didn’t know another one exploded. Jesus,” says Atencio. He’d heard of an explosion from his uncle, but thought it was connected to the spill at the neighboring well. It was during an interview with Capital & Main that he learned it was a separate accident.

“There’s all these highly dangerous facilities all around my grandma’s house,” he says.

“There was a big old explosion. It shook the ground,” says Wilbert Atencio, Mario’s uncle. He was in his mother’s garage when it happened, at around 7.45 in the evening. “I thought it was like an earthquake or something.”

On that February evening two years ago, Wilbert hopped in his truck and drove a quarter-mile down the road toward the sound only to find the road blocked by contractor trucks with their lights flashing. “We have livestock and everything, and we wanted to know what was going on,” he says. But he couldn’t see the fire or the wellsite itself, as it sits on the other side of a rise down a side road. The contractors said he couldn’t pass and told him to go home. He later saw state police, emergency medical technicians and fire engines arrive.

Three of those vehicles came from the volunteer fire department in Cuba, nearly an hour’s drive away. According to the fire chief, Rick Romero, they got the call a little before 8pm, arrived at the burning well around 9.45 and didn’t leave the scene until 12.40 in the morning. Engines from neighboring San Juan county also responded, and both departments sprayed the well with water and fire-suppressing foam for more than an hour before it was extinguished.

“We graze on this land, we live on this land,” says Wilbert. But he doesn’t see the oil drilling industry changing in his neighborhood anytime soon. It’s been going on for decades, and he thinks it will keep drilling into the future.

“You know, they’re drilling everywhere.” Wilbert says this in a call from a jobsite in Palmdale, California. There are oil and gas wells there, too.

Norm Gaume is a retired water engineer and the former director of the New Mexico interstate stream commission. He has a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and a master’s degree in civil engineering, with a focus on water and wastewater engineering, from New Mexico State University. Early in his career he spent a dozen years as an operations and maintenance manager of Albuquerque’s water, wastewater and stormwater pumping systems.

Recently, he and Peter Coha, a retired mathematician who did large dataset analysis in an automation group at Intel, pulled reams of files from OCD’s online system that tracks spills and other accidents in the oil and gas industry across New Mexico.

They found thousands upon thousands of accidents that are chalked up to everything from lightning strikes to vandalism to valve failures. But the two biggest causes of accidents – by far – are equipment failure, followed by corrosion.

To Gaume, those simply aren’t good enough reasons for oil and gas wells to spill their toxic contents. Equipment failure means you’re not maintaining your equipment, he says, and corrosion failure means you’re using the wrong components. Add to that accidents caused by human error, and three-fourths of all accidents in their accounting were preventable, if stronger regulation were in place to nudge producers in line.

Absolving Your Sins and CYA: Corporations Embrace Voluntary Codes of Conduct

“Spill prevention is voluntary,” says Gaume. There are no laws punishing producers for spills. “And some operators choose to spend money to prevent spills, and some apparently don’t.”

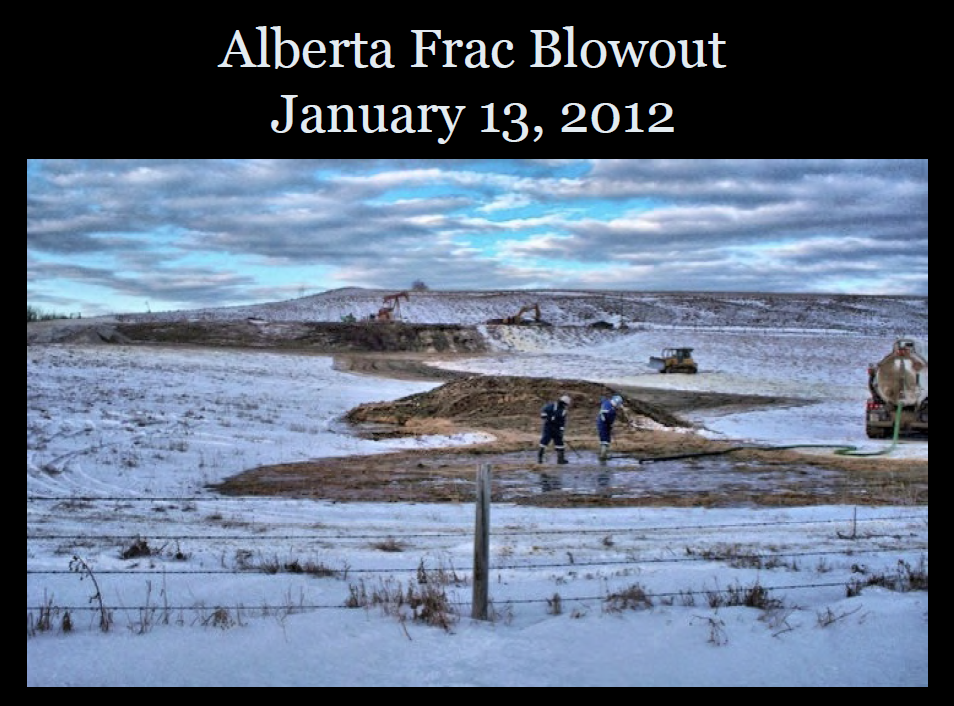

Alberta Frac Spill Interlude:

End Alberta Frac Spill Interlude.

Gaume and Coha find this idea reflected again in another view of the records, which shows vast differences between well operators when it comes to numbers of accidents compared with how much oil or gas they’re producing.

“Some operators do a pretty good job” of producing with few spills, Gaume says. “Some have rates of spill that are 20 times as high [as other producers].”

Taken together, he says, their data analysis shows that most spills are preventable.

In the chart of producers compiled by Gaume and Coha, Enduring Resources produces quite a bit of oil and gas with comparatively few accidents. But according to OCD’s reports, human error and equipment failure caused the accidents in 2019.

To Gaume, despite the company’s generally good record, those reasons are not acceptable.

In August 2020, a pipeline operated by a different company, Harvest Four Corners, of Houston, leaked natural gas into an ephemeral wash about 50 miles away from the Enduring Resources accidents.

Even though crews began cleanup immediately, Harvest got hit with a $92,000 fine from OCD because it neglected to report the spill for 44 days. State regulations require phoning in major incidents within 24 hours and filing a written report within 15 days. Minor incidents – those involving less than 25 barrels of fluids or 500 McF of gas – require only a written report within 15 days of finding the release.

Enduring Resources faced no fines and paid no penalties for either the fracking spill or the well fire. There is no violation in spilling fracking waste or wells catching fire in New Mexico. The only violation is in not reporting accidents. Since Enduring Resources promptly reported both, OCD played a supervisory role that consisted of approving the remediation plan and site cleanup.

Of all of the agencies that were eventually notified and kept abreast of the spill – OCD, BIA, BLM, the US Environmental Protection Agency and the US army corps of engineers – none levied a fine or sanction.

According to paperwork filed with OCD, three months after Enduring Resources’ well spilled 1,400 barrels of fracking waste near Atencio’s grandmother’s house in 2019, it had another accident, spilling 20 barrels of crude oil straight into the ground. Half of it was recovered. It was deemed a minor spill by OCD rules and the case was closed after it was reported by Enduring Resources.

Standing in the biting wind on the dirt road next to the spill site in mid-March, Mario Atencio wonders aloud what was in the fracking mixture that spilled on his family’s land and ran down the wash in front of him.

Measurements included in the final report that Enduring Resources filed with OCD show that the water table is only 50ft below the surface. His family has run sheep and sometimes cattle on the land, and the animals would drink from the wash where the toxic mixture sank in. Farther down the creek is a hand pump where people fill a water tank for livestock.

Atencio believes the water table is probably unusable now. “This used to support 40, 50 head of sheep,” he says. “And now the whole water is contaminated.”

Recently, some state legislators tried to pass new rules that would have imposed fines for spilling fracking waste, or so-called produced water. But the bill died in committee in the just-completed New Mexico legislative session.

Gaume and Atencio both testified in favor of the legislation. But the majority of committee members agreed with industry lobbyists opposed to the proposed rules, who said that further regulations could drive the oil and gas industry out of New Mexico.

Meanwhile, oil and gas production remains robust. In a year buffeted by massive downturns in demand and prices brought on by the Covid-19 crisis, New Mexico pumped more hydrocarbons out of the ground than ever before.

As Atencio stands near the two wells on that windy day in March, semi trucks hauling sand and fracking equipment whip up and down the washboard road. “Oil companies are supposed to be our business partners. Look at this road,” he says, pointing at the dirt. It’s a sore point with him that the oil companies didn’t even build good dirt roads connecting the wellsites. “Yeah,” he says, “we’re business partners.”

It’s part of what Tso calls the “fracking tsunami”.

Industry rolled through Native American lands, disrupting everything from sleep patterns to finances, and left little behind. In the end there is no community center, no nearby fire station that can handle chemical fires, no money for higher education and no good roads.

And those abandoned mission buildings in Counselor – the school, the church, the apartments? The Navajo Nation bought the town and those buildings for $1m in 2007 with plans to refurbish them. But Tso says they found out later they were built with asbestos, and it will cost another $2.6m to tear them down and replace them.

“It happened on Indian land,” says Tso. “So it’s trivialized. It’s of no big concern.”

Rates of Parkinson’s disease are exploding. A common chemical may be to blame, Researchers believe a factor is a chemical used in drycleaning and household products such as shoe polishes and carpet cleaners by Adrienne Matei, 7 Apr 2021, The Guardian

Asked about the future of Parkinson’s disease in the US, Dr Ray Dorsey says, “We’re on the tip of a very, very large iceberg.”

Dorsey, a neurologist at the University of Rochester Medical Center and author of Ending Parkinson’s Disease, believes a Parkinson’s epidemic is on the horizon. Parkinson’s is already the fastest-growing neurological disorder in the world; in the US, the number of people with Parkinson’s has increased 35% the last 10 years, says Dorsey, and “We think over the next 25 years it will double again.”

Most cases of Parkinson’s disease are considered idiopathic – they lack a clear cause. Yet researchers increasingly believe that one factor is environmental exposure to trichloroethylene (TCE), a chemical compound used in industrial degreasing, dry-cleaning and household products such as some shoe polishes and carpet cleaners.

![]() And used in hydraulic fracturing (see also “Chemicals Detected in the Air in association with shale gas drilling, production and distribution”) but our corporate-controlled authorities and politicians refuse to make companies fully disclose their toxic frac additives, not even when injecting them directly into drinking water aquifers as Encana/Ovintiv did in Rosebud Alberta and Pavillion Wyoming. Authorities and companies claim “trade secrets” protect corporate recipes, which is bullshit – spewed to the harmed to enable companies poisoning us, our homes and communities, drinking water, air, foods and land. Trade secrets are not allowed in lawsuits in Alberta, yet Encana still has not disclosed to me what additives the company injected into water I ingested and bathed in (bathing in toxic water can be more harmful to health than ingesting it), as did my loved ones and neighbours. And no regulator is compelling Encana or any other frac’er to hand over the recipes of their toxic brews.

And used in hydraulic fracturing (see also “Chemicals Detected in the Air in association with shale gas drilling, production and distribution”) but our corporate-controlled authorities and politicians refuse to make companies fully disclose their toxic frac additives, not even when injecting them directly into drinking water aquifers as Encana/Ovintiv did in Rosebud Alberta and Pavillion Wyoming. Authorities and companies claim “trade secrets” protect corporate recipes, which is bullshit – spewed to the harmed to enable companies poisoning us, our homes and communities, drinking water, air, foods and land. Trade secrets are not allowed in lawsuits in Alberta, yet Encana still has not disclosed to me what additives the company injected into water I ingested and bathed in (bathing in toxic water can be more harmful to health than ingesting it), as did my loved ones and neighbours. And no regulator is compelling Encana or any other frac’er to hand over the recipes of their toxic brews.![]()

To date, the clearest evidence around the risk of TCE to human health is derived from workers who are exposed to the chemical in the work-place. A 2008 peer-reviewed study in the Annals of Neurology, for example, found that TCE is “a risk factor for parkinsonism.” And a 2011 study echoed those results, finding “a six-fold increase in the risk of developing Parkinson’s in individuals exposed in the workplace to trichloroethylene (TCE).”

Dr Samuel Goldman of The Parkinson’s Institute in Sunnyvale, California, who co-led the study, which appeared in the Annals of Neurology journal, wrote: “Our study confirms that common environmental contaminants may increase the risk of developing Parkinson’s, which has considerable public health implications.” It was off the back of studies like these that the US Department of Labor issued a guidance on TCE, saying: “The Board recommends […] exposures to carbon disulfide (CS2) and trichloroethylene (TCE) be presumed to cause, contribute, or aggravate Parkinsonism.”

TCE is a carcinogen linked to renal cell carcinoma, cancers of the cervix, liver, biliary passages, lymphatic system and male breast tissue, and fetal cardiac defects, among other effects. Its known relationship to Parkinson’s may often be overlooked due to the fact that exposure to TCE can predate the disease’s onset by decades. While some people exposed may sicken quickly, others may unknowingly work or live on contaminated sites for most of their lives before developing symptoms of Parkinson’s.

Those near National Priorities List Superfund sites (sites known to be contaminated with hazardous substances such as TCE) are at especially high risk of exposure. Santa Clara county, California, for example, is home not only to Silicon Valley, but 23 superfund sites – the highest concentration in the country. Google Quad Campus sits atop one such site; for several months in 2012 and 2013, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found employees of the company were inhaling unsafe levels of TCE in the form of toxic vapor rising up from the ground beneath their offices.

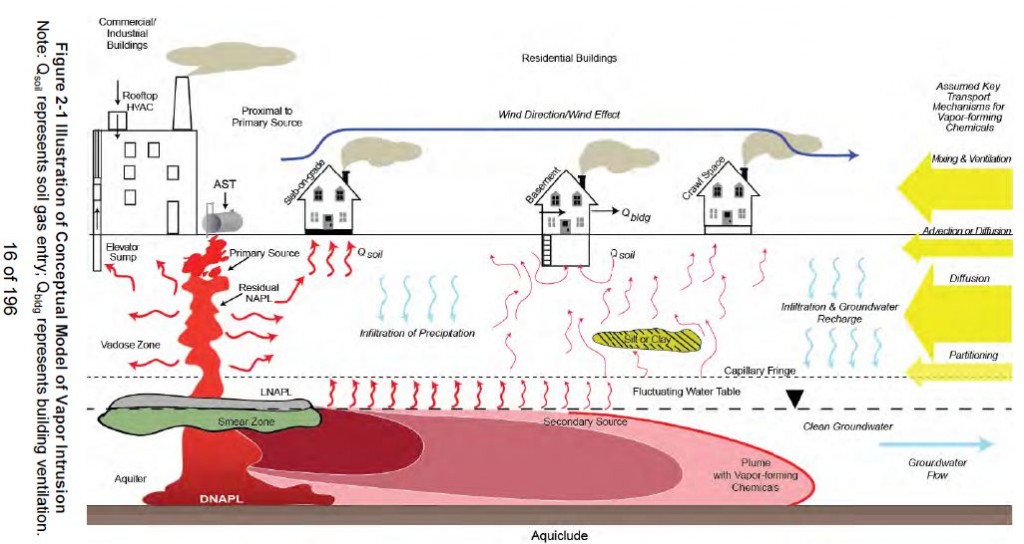

US EPA Vapour Intrusion Interlude:

End US EPA Vapour Intrusion Interlude.

While some countries heavily regulate TCE (its use is banned in the EU without special authorization) the EPA estimates that 250m lb of the chemical are still used annually in the US, and that in 2017, more than 2m lb of it was released into the environment from industrial sites, contaminating air, soil and water. TCE is currently estimated to be present in about 30% of US groundwater (the non-profit Environmental Working Group created its own map of TCE-contaminated water sites nationwide), though researcher Briana de Miranda, a toxicologist who studies TCE at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, says: “We are under-sampling how many people are exposed to TCE. It’s probably a lot more than we guess.”

Under EPA regulations, it’s considered “safe” for TCE to be present in drinking water at a maximum concentration of five parts per billion. In severe cases of contamination, such as that which occurred at Camp Lejeune, a North Carolina marine corps, between the 1950s and late 1980s, people are believed to have been exposed to up to 3,400 times the level of contaminants permitted by safety standards. A memorial site known as “Babyland” honors the children of military personnel who died after they or their pregnant mothers were exposed to TCE-tainted water while living on the base.

While De Miranda says researchers do not believe low concentrations of TCE in drinking water specifically are enough to cause illness, Dorsey doesn’t think it’s an overstatement to say US groundwater could be giving people Parkinson’s disease. “Numerous studies have linked well water to Parkinson’s disease, and it’s not just TCE in those cases, it can be pesticides like paraquat, too,” he says, referencing a lethal weedkiller the US still uses despite it being phased out in the EU, Brazil and China.

Using activated carbon filtration devices (like Brita filters) can help reduce TCE in drinking water, yet bathing in contaminated water, as well as inhaling vapours from toxic groundwater and soil, can be far more difficult to avoid. ![]() Health experts advised me that the toxic chemicals found in my well water after Encana/Ovintiv illegally frac’d the aquifers that supply my community are more harmful bathed in than ingested, notably when inhaled while showering or breathing them with hydrocarbons escaping via household taps forced open by the extreme concentrations of migrating frac’d gases in my water. When my well was connected to my home, my water taps sounded like a train coming, so much gas was whistling out of them.

Health experts advised me that the toxic chemicals found in my well water after Encana/Ovintiv illegally frac’d the aquifers that supply my community are more harmful bathed in than ingested, notably when inhaled while showering or breathing them with hydrocarbons escaping via household taps forced open by the extreme concentrations of migrating frac’d gases in my water. When my well was connected to my home, my water taps sounded like a train coming, so much gas was whistling out of them.![]()

De Miranda says policy and effective government intervention are crucial when it comes to testing, monitoring and remediating TCE contaminated sites, and that it’s important to raise awareness of TCE’s role in surging rates of Parkinson’s. Failure to address the issue will not only continue to negatively affect people’s health, but will exacerbate the adult home care crisis that has already left 50 million Americans responsible for providing care to sick loved ones, as Parkinson’s is characterized by slow, progressive degeneration and has no cure.

In May 2020, Minnesota became the first state to ban TCE; New York followed suit last December, as should more states, especially as federal action on the issue has lagged. Given the negative health effects of TCE have been documented in the Journal of the American Medical Association since 1932, it’s well past time for the US to stop using it, and to better protect its civilians from hazardous chemicals that put lives at risk.

Trichloroethylene (TCE) Is A Risk Factor For Parkinsonism, Study Shows by Wiley-Blackwell, Jan 9, 2008, ScienceDaily

Parkinson’s disease, the most common neurodegenerative movement disorder caused by aging, can also be caused by pesticides and other neurotoxins. A new study found strong evidence that trichloroethylene (TCE) is a risk factor for parkinsonism, a group of nervous disorders with symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease.

TCE is a chemical widely used in industry that is also found in drinking water, surface water and soil due to runoff from manufacturing sites where it is used. ![]() And or spilled, injected by companies that don’t give a damn, like Encana/Ovintiv.

And or spilled, injected by companies that don’t give a damn, like Encana/Ovintiv.![]()

Led by Don M. Gash and John T Slevin, of the University of Kentucky in Lexington, KY, researchers conducting a clinical trial of 10 Parkinson’s disease patients came across a patient who described long-term exposure to TCE, which he suspected to be a risk factor in his disease. TCE has been identified as an environmental contaminant in almost 60 percent of the Superfund priority sites listed by the Environmental Protection Agency and there has been increasing concern about its long term effects.

The patient noted that some of his co-workers had also developed Parkinson’s disease, which led to the current study of this patient and two of his co-workers diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease who underwent neurological evaluations to assess motor function. All of these individuals had at least a 25 year history of occupational exposure to TCE, which included both inhalation and exposure to it from submerging their unprotected arms and forearms in a TCE vat or touching parts that had been cleaned in it.

In addition, questionnaires about experiencing signs of Parkinson’s disease, such as slowness of voluntary movement, stooped posture and trouble with balance, were mailed to 134 former workers. The researchers also conducted studies in rats to determine how TCE affects the brain.

The results showed that 14 former employees who reported three or more parkinsonian signs worked close to the TCE source, were found to exhibit signs of parkinsonism when they were examined and were significantly (up to 250 percent) slower in fine motor hand movements than age-matched controls. Clinical exams of 13 patients who reported no signs of parkinsonism revealed that they worked in the same areas as the symptomatic workers or further from the TCE vat, they exhibited some mild features of the condition and their fine motor movements were also significantly slower than controls, although they were faster than the group with symptoms.

The rat studies showed that TCE exposure inhibited mitochondrial function (which in humans is associated with a wide range of degenerative diseases) in the substantia nigra, an area in the brain that produces dopamine and whose destruction is associated with Parkinson’s disease. Specifically, Complex 1, an enzyme important in energy production, was significantly reduced in the substantia nigra. Dopamine neurons in this area also showed degenerative changes following TCE administration.

The authors acknowledge that while the study was not a large scale epidemiological investigation, the results demonstrate a strong potential link between chronic TCE exposure and parkinsonism. “It will be important to follow the progression of movement disorders in this cohort over the next decade to fully assess the long-term health risks from trichloroethylene exposure,” they state. Although previous studies identified pesticides as a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease, the drug MPTP was previously the only mitochrondrial neurotoxin linked to the disease.

The authors conclude: “Trichloroethylene is implicated as a principal risk factor for parkinsonism based on its dopaminergic neurotoxicity in animal models, the high levels of chronic dermal and inhalation exposure to trichloroethylene by the three workers with Parkinson’s disease, the motor slowing and clinical manifestations of parkinsonism in co-workers clustered around the trichloroethylene source, and the mounting evidence of neurotoxic effects in other reports of chronic trichloroethylene exposure.”

Journal article: “Trichloroethylene: Parkinsonism and Complex 1 Mitochondrial Neurotoxicity,” Don M. Gash, Kathryn Rutland, Naomi L. Hudson, Patrick G. Sullivan, Guoying Bing, Wayne A. Cass, Jignesh D. Pandya, Mei Liu, Dong-Yong Choi, Randy L. Hunter, Greg A. Gerhardt, Charlie D. Smith, John T. Slevin, T. Scott Prince, Annals of Neurology, December 2007.