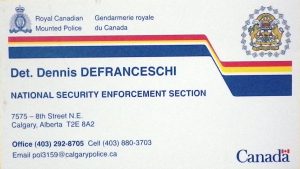

Harper’s anti-terrorist RCMP squad trespassed, without a warrant, on my private property after the Alberta gov’t, Encana/Ovintiv and AER were served with my legal papers. I was in my own home, not attending any protest (contrary to what media and NGOs, claim, I am not an activist). It seems my only crime was warning the public about frac harms and filing a lawsuit against Encana et al, trying to protect the public interest. The squad wanted into my home. I refused, told them I didn’t trust them or their surveillance techniques.

“We don’t do surveillance,” they replied.

I laughed at their absurdity and didn’t let them in (I was terrified, I live alone rurally).

I let them interrogate me outside. It was a cold February day; I gave the lead interrogator a metal chair, I sat in a wooden one; I offered blankets, tissues for their runny noses, hot tea with honey, all declined.

When the officers were done trying to scare me and get me to admit to crimes I had not committed (like AER’s lawyer Rick McKee failed at three years earlier trying to get evidence after the fact to justify the “regulator” violating my Charter rights), they left, shoulders slumped, knowing their mission for Herr Harper and buddy Encana to snare me had failed.

Explosive report reveals RCMP’s toxic culture of racism, misogyny and homophobia by Pam Palmater, December 4, 2020, Rabble.ca

RCMP’s toxic culture

Racism, misogyny and homophobia — these are the characteristics of Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) toxic culture according to a new report released last month.

The report, “Broken Dreams Broken Lives,” was written by former Supreme Court of Canada justice Michel Bastarache, who had been engaged as an independent assessor to review the more than 3,000 claims of sexual harassment experienced by women who worked for the RCMP. He found that the experiences of these women in the RCMP were nothing short of devastating. ![]() In my experience, Encana/Ovintiv illegally frac’ing Rosebud and Redland’s drinking water aquifers, repeatedly, injecting 18 Million litres frac fluid directly into them, is like being repeatedly raped by Christian married pedophiles. When will there be an “independent assessor” reviewing the many frac’d water supplies and frac-harmed Canadians suffering betrayal after betrayal by politicians, regulators, the courts, police/RCMP, and even one’s own lawyers (Cory Wanless and Murray Klippenstein)?

In my experience, Encana/Ovintiv illegally frac’ing Rosebud and Redland’s drinking water aquifers, repeatedly, injecting 18 Million litres frac fluid directly into them, is like being repeatedly raped by Christian married pedophiles. When will there be an “independent assessor” reviewing the many frac’d water supplies and frac-harmed Canadians suffering betrayal after betrayal by politicians, regulators, the courts, police/RCMP, and even one’s own lawyers (Cory Wanless and Murray Klippenstein)?![]()

In addition to those women who suffered from violent sexual assaults by their male RCMP colleagues, many women have been left with deep psychological injuries which range from major depressive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder to substance dependence and even suicide. Bastarache emphasized that “it is impossible to fully convey the depth of the pain that the assessors witnessed” and that “no amount of financial compensation can undo the harm” these women and their families experienced at the hands of the RCMP in all provinces and territories.

RCMP culture eats policy

The real tragedy is that none of this is news — not to the RCMP or the federal and provincial governments. All of them have known about this long-standing, widespread problem of racism, misogyny, homophobia and violence within the RCMP for many decades — through both internal and external reports and litigation.

The RCMP is a male-dominated, paramilitary organization whose powerful, toxic culture has prevailed despite internal policy changes. They are impervious to change because “culture eats policy every time.” The RCMP are invested in the status quo and will not change: ![]() In my experiences, it’s the same with “regulators” like AER (100% industry-funded), the legal industry (regulated by lawyers) and judicial industry (regulated by judges).

In my experiences, it’s the same with “regulators” like AER (100% industry-funded), the legal industry (regulated by lawyers) and judicial industry (regulated by judges).![]()

“Indeed, there are strong reasons to doubt that the RCMP has this capacity or the will to make the changes necessary to address the toxic aspects of its culture.”

Sexualized violence

One of the most disturbing aspects of the report is how male RCMP members and leaders saw women as “fresh meat” to be used and abused as they saw fit.

The stories told to the assessors “shocked them to their core.” In addition to “serious acts of penetrative sexual assaults,” male RCMP officers from all over Canada engaged in horrific acts of sexual harassment and abuse including:

- unwelcome sexual touching;

- men exposing their penises;

- making degrading comments about women’s bodies;

- humiliating name-calling;

- spreading violent and obscene pornography forcing women to watch it;

- being handcuffed to men’s toilets and locked in cells;

- leaving dildos and used condoms on their desks;

- being accused of selling sex;

- outing their sexual orientation without their consent; and

- stalking and bullying by male RCMP demanding sexual favours from women.

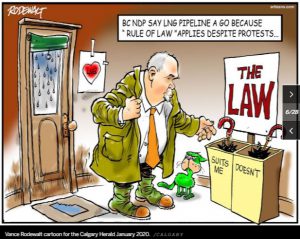

Compare the above RCMP acts to operating as taxpayer-funded thugs serving multinational corporations like Encana/Ovintiv, abusing and or conning citizens, families, communities that courageously say no to frac’ing and other toxic oil and gas industry harms, or go public trying to warn others of harms already illegally done, with politicians, and regulators unwilling or too cowardly to uphold the “rule of law,” and courts intentionally publishing lies in rulings.

Compare the above RCMP acts to operating as taxpayer-funded thugs serving multinational corporations like Encana/Ovintiv, abusing and or conning citizens, families, communities that courageously say no to frac’ing and other toxic oil and gas industry harms, or go public trying to warn others of harms already illegally done, with politicians, and regulators unwilling or too cowardly to uphold the “rule of law,” and courts intentionally publishing lies in rulings.

RCMP Targeted Indigenous women

The report details how the RCMP treated Indigenous women even more poorly than other women.

In addition to the humiliating and degrading behaviours experienced by other women in the RCMP, Indigenous women were also referred to as “squaw” and “smoked meat” and “were, at times, forced to watch RCMP members treat other Indigenous people brutally.”

Their male RCMP colleagues took advantage of the fact that many of these Indigenous women were young and came from small or remote communities and were not accustomed to this type of toxic culture.

“Indigenous women, particularly those who had been abused as children, were preyed upon by their male colleagues for sexual favours.”

“Few bad apples” myth busted

The RCMP has long relied on the “few bad apples” justification to protect their organization’s status quo which has resulted in so much pain and suffering for women in the RCMP.

Despite the fact that RCMP members and leaders have long denied the systemic and cultural nature of their racism, misogyny and homophobia, this report found that sexual harassment in the RCMP exists “at every level of the RCMP and in every geographic area of Canada” and is “embedded in its culture.” Even those members and leaders who are well-intentioned make choices to accept this culture and stay silent on the injustices. ![]() Creepily like too many in Canada’s legal and judicial industry.

Creepily like too many in Canada’s legal and judicial industry.![]()

“The reality is, however, that even honourable members (and well-intentioned leaders) have been required to conform to (or at least accept) the underlying culture, which they have, for the most part, had to adopt in order to succeed in their career. Those who do not accept the culture are excluded.”

RCMP cannot be fixed from within

This report makes it very clear that the RCMP cannot be fixed from within. They simply refuse to acknowledge that there are significant problems that are systemic and deeply rooted within their culture. ![]() As long as racist, misogynistic, homophobic, bigoted (and largely rich white) politicians appoint our judges, nothing will change, except the lies will get louder. Carry abusively on, as intended by PM John A MacDonald, to protect the white rich.

As long as racist, misogynistic, homophobic, bigoted (and largely rich white) politicians appoint our judges, nothing will change, except the lies will get louder. Carry abusively on, as intended by PM John A MacDonald, to protect the white rich.![]()

Their toxic culture of racism, misogyny and homophobia is “powerful and presents an obstacle to change.”

Furthermore, “Financial settlements of class-action lawsuits will not change this culture.”

The assessors found that the RCMP ![]() like judges, the Canadian Judicial Council, law societies and too many lawyers?

like judges, the Canadian Judicial Council, law societies and too many lawyers?![]() “are invested in the status quo and will not likely want to make the necessary changes to eradicate this toxic culture.”

“are invested in the status quo and will not likely want to make the necessary changes to eradicate this toxic culture.”

In fact, many of the women that had been interviewed felt that there was no chance for reform within the RCMP and some suggested it was time that it be replaced. This is what many Black and Indigenous peoples have been saying for decades and why the calls for the RCMP to be abolished have grown stronger in recent years.

And finally, the report concluded that the RCMP are not able to either investigate or remediate these problems.

“These men were often not held accountable for their actions. Indeed, the assessors were told that one tactic used by the RCMP to resolve complaints of sexual harassment was to promote and transfer these men.”

![]() Copying the “silent shuffle” of pedophile-infested churches, notably catholic, enabled by:

Copying the “silent shuffle” of pedophile-infested churches, notably catholic, enabled by:

And, as long as lawyers help abusers “settle and gag” and worse, pay off the harmed with the public’s money – never that of the men causing the harms, Canada’s facilitated rape of children, women, immigrants, the poor, marginalized, Indigenous and our environment will only escalate.![]()

What’s next?

It is clear from this report that the RCMP has neither the will nor the ability to address its toxic culture and its widespread sexualized violence within its ranks.

It must also be kept in mind that this is just one of many class actions against the RCMP. The RCMP’s toxic culture of racism, misogyny and homophobia, together with widespread sexualized violence, represents a major public safety issue for women generally, and especially for Indigenous, Black and marginalized women and girls.

We need Canadians to call on Canada to:

- Open the books at the RCMP so we can hold those who preyed on women to account;

- Conduct an independent investigation into the RCMP’s similar actions towards Indigenous peoples;

- Make reparations to Indigenous peoples who have suffered from RCMP harassment, over-arrests, racism, brutality, sexualized violence and killings; and

- Dismantle the RCMP once and for all.

Pamela D. Palmater is a Mi’kmaw lawyer and member of the Eel River Bar First Nation in New Brunswick. She teaches Indigenous law, politics and governance at Ryerson University and heads Ryerson’s Centre for Indigenous Governance. This article was originally published in Indigenous Nation.

One of the comments:

When the Doctor is in the house , you’re gonna hear some strong medicine. Chalk up another horror produced by supposedly centrist politics.

Real democracy and rule of law would not allow this to continue. Only a deceptive extremism can produce such a history.

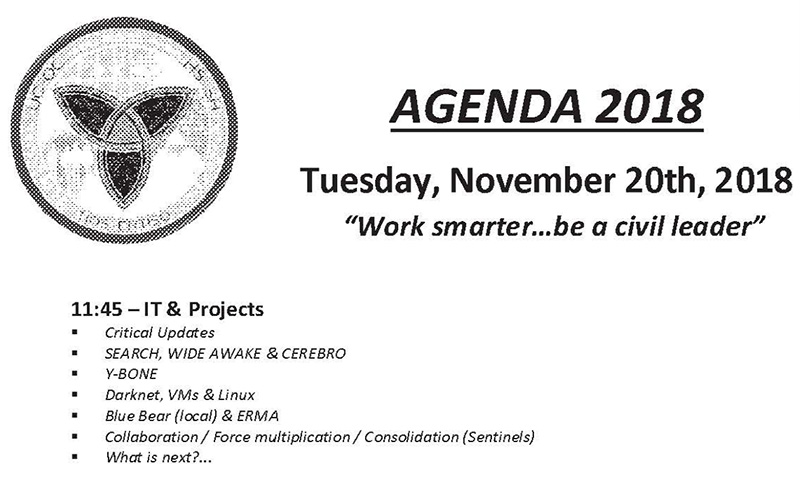

The RCMP’s X-Men Fixation Is More Sinister than Comic, The force’s ‘Project Wide Awake’ name choice shows a broken police culture that harms Black and Indigenous communities by Daniella Barreto, Dec 9, 2020, TheTyee.ca

The RCMP’s decision to name its Project Wide Awake online surveillance program after mutant trackers in the X-Men comic book series might seem like harmless fun.

But viewed against the scathing revelations of systemic racism and misogyny in police forces nationwide, it’s a troubling glimpse into police culture that unmasks the institution’s casual dehumanization of marginalized groups.

The Tyee first revealed the existence of Project Wide Awake, an operation monitoring individuals’ Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and other social media activity, in 2019.

In the X-Men comic series, Project Wide Awake is a covert government program that employs mutant-hunters, or “sentinels,” to monitor, track down and exterminate human mutants — the X-Men.

In the real world, Project Wide Awake is the RCMP’s large-scale online surveillance program designed to monitor internet users and political protest activity. In the RCMP’s version, Canadian residents are the mutants being targeted by “the hunters.”

But not everyone is an equal target. Due to power dynamics and social discrimination, poor, Black and Indigenous communities are disproportionately policed and surveilled. They’re often cast as the “bad guys.”

The operation’s mutant-hunting eponym is not coincidental or even an isolated incident within the RCMP. Documents obtained by The Tyee exposed references to two projects connected to Project Wide Awake with names plucked directly from the X-Men series: Sentinel (mutant hunting robots in the comic book series) and Cerebro (a powerful device to detect mutants’ locations).

While the RCMP was not forthcoming with Tyee reporter Bryan Carney about these projects’ exact purposes, their names alone and their mention in a covert operations meeting agenda for Tactical Internet Operations Support unit suggest further surveillance operations.

X-Men isn’t the only Marvel comics reference to have popped up in Canadian policing.

Earlier this year, a Toronto officer was photographed wearing a skull emblem for the Punisher, Marvel’s outlaw character who delivers vigilante justice. The Punisher features prominently in pro-police and white supremacist merchandise despite the creator’s efforts to scrub the association.

Society tells us that police exist to bring justice. Like comic book characters, this is fiction. Across the country, Black and Indigenous communities bear the brunt of policing’s impacts and are disproportionately targeted in street checks by police forces. They also experience disproportionate levels of police violence. Drug users, sex workers and people who are homeless are often harmed by the police through active harassment and violence or neglect.

Canada is built on policies that explicitly or implicitly operate to wipe out Indigenous peoples from their lands and suppress Black communities. ![]() And help corporations rape aquifers, public health, communities, families and our environment, and give them billions of our tax dollars to do it.

And help corporations rape aquifers, public health, communities, families and our environment, and give them billions of our tax dollars to do it.![]() Drug and sex work criminalization forces people into isolated situations so they can avoid the police, but they are then exposed to other dangers such as overdoses and client violence.

Drug and sex work criminalization forces people into isolated situations so they can avoid the police, but they are then exposed to other dangers such as overdoses and client violence.

When some groups are cast as “other,” “different” or “foreign” by dominant society, ![]() Or speak out about illegal frac operations or say no to frac’ing to try to protect community drinking water and public health

Or speak out about illegal frac operations or say no to frac’ing to try to protect community drinking water and public health![]() they are perceived as a threat to be watched and managed, subject to prejudice, exclusion and dehumanization. In this context, the language and framing police choose matters.

they are perceived as a threat to be watched and managed, subject to prejudice, exclusion and dehumanization. In this context, the language and framing police choose matters.

The RCMP is mythologized in the Canadian imagination as an honourable force on horseback sporting the distinctive red uniform, a symbol of national pride and bravery.

In fact, as demonstrated against the Wet’suwet’en land defenders earlier this year, the RCMP is an increasingly militarized outfit designed to enforce colonial laws and control the population through threat of force, like other police forces in Canada.

Historically, RCMP officers were instrumental to the colonial project in expanding Canada’s rule in the West, dragging Indigenous children away from their families and cultures and dropping them into the arms of priests and nuns where they experienced the unthinkable horrors of residential schools.

The RCMP has consistently operated against the safety of Indigenous peoples from inaction surrounding cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women to killing Indigenous people while performing wellness checks to surveilling and arresting land defenders.

The values that underpin policing in Canada necessarily reflect the values of a colonial state interested in dispossessing Indigenous peoples of their land.

Black people have a different yet similar experience of violence and exclusion in Canada. They are often criminalized, surveilled and policed in public space and have been subject to a long history of enslavement, segregation, discriminatory immigration practices and police violence.

Popular media often portrays Black people as inherently criminal, violent, sexually deviant and possessing superhuman strength. These are widespread tropes that foment fear and justify suspicion and aggression towards Black people, including in Canadian policing. For instance, in 2016, the RCMP categorized a daytime vigil outside the Vancouver Art Gallery to remember the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile as a “serious crime-unfolding event” in a document related to its social media surveillance of the group.

The same document states that there was no indication of violence. This shows how police assume Black people are criminals, which might have served to justify social media surveillance in the first place.

If officers are institutionally and socially primed to see Black people as a threat, then the stage is set for the surveillance, contact and violence that has resulted in the needless criminalization and deaths of too many in Canada.

Recognizing a problem in the RCMP, the federal government provided the force with $238 million for body cameras this month. However, there is little evidence that body cameras do anything but record police violence. Even when police violence is recorded, impunity is common.

Body cameras are an expensive and unproven way to try to improve police accountability through technology while effectively increasing police surveillance powers. In fact, body cameras can be used as an enhanced way to criminalize subjects by letting police create a massive database of surveillance footage of communities that are already over-policed. This data has the potential to be used by the RCMP’s Tactical Internet Operations Support unit against those protesting social injustice.

Ultimately, something as trite as a comic book name for a spy program simply corroborates the mountains of evidence that policing in Canada is a toxic and harmful institution.

We must interrogate policing as we know it. We must demand our governments support communities with evidence-backed approaches that produce positive outcomes on a broad scale. Investing in the social determinants of health will have a lasting impact. Instead of funding increased surveillance and policing, governments must fund education, mental health and social support programs led by communities themselves, provide housing, and decriminalize drugs and sex work.

Building real community safety demands we move from a mindset of “fighting crime” to one of ending harm.

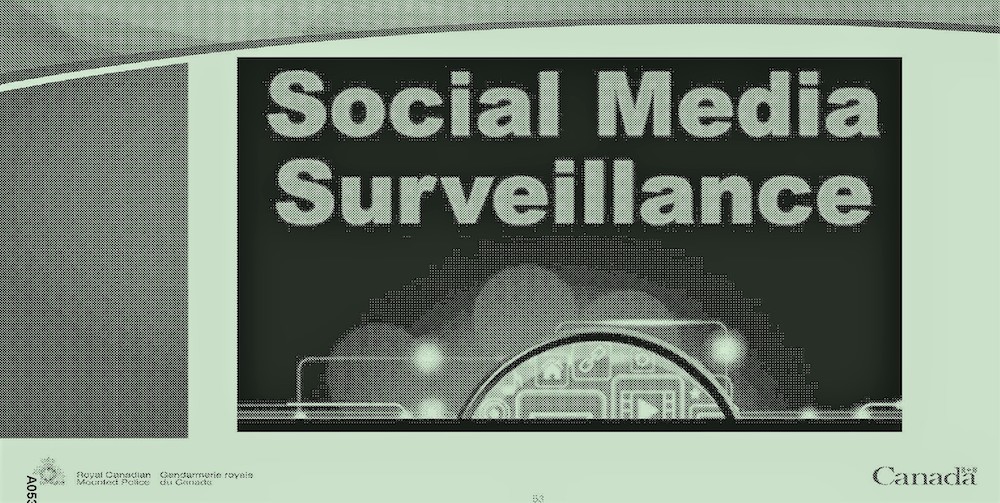

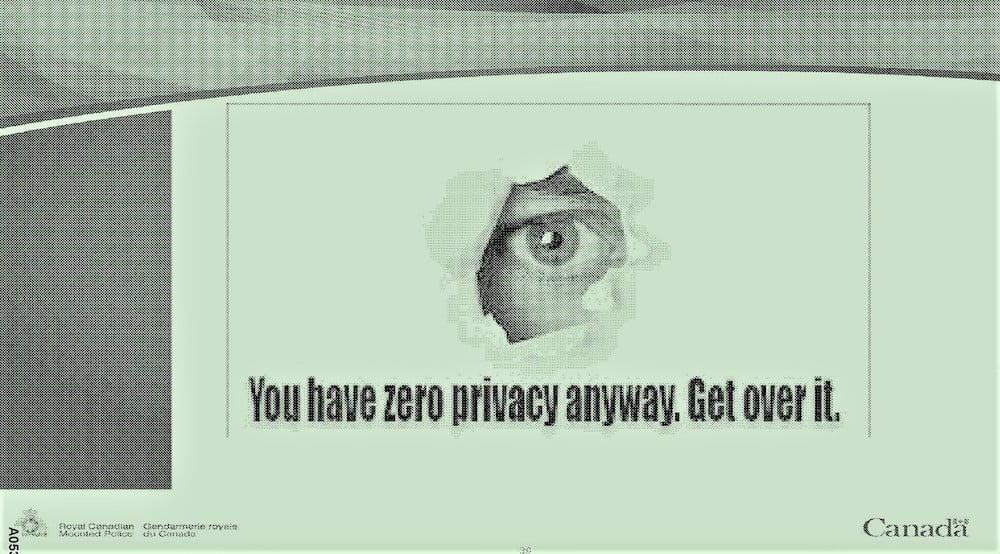

‘You Have Zero Privacy’ Says an Internal RCMP Presentation. Inside the Force’s Web Spying Program, ‘Project Wide Awake’ files obtained by The Tyee show efforts to secretly buy and use powerful surveillance tools while downplaying capabilities by Bryan Carney, 16 Nov 2020, TheTyee.ca

Excellent visuals at link.

A 3,000-page batch of internal communications from the RCMP obtained by The Tyee provides a window into how the force builds its capabilities to spy on internet users and works to hide its methods from the public.

The emails and documents pertain to the RCMP’s Tactical Internet Operation Support unit based at the national headquarters in Ottawa and its advanced web monitoring program called Project Wide Awake.

The files include an internal RCMP presentation that contradict how the force has characterized Project Wide Awake to Canada’s privacy commissioner and The Tyee in past emails. A slide labels the program’s activities “Social Media Surveillance,” despite the RCMP having denied that description applied.

Communications show one high-level officer blasting the project before leaving the RCMP for Chinese tech firm Huawei.

Other members were jokingly dismissive of public concerns about privacy violations — a training slide for the project says: “You have zero privacy anyway, get over it.”

In seeking contract renewals and wider capabilities, the RCMP claimed its spying produced successful results, including finding online a “direct threat” to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

The documents reveal the RCMP:

- Gained permission to hide sole-source contracts for Project Wide Awake from the public through a “national security exception.”

- Discussed “tier three” covert operations involving the use of proxies — intermediary computers located elsewhere — to hide RCMP involvement with spying activities.

- Purchased software with an aim to search “Darknet,” which it defined to include “private communications” and those from “political protests.”

- Has used a tool to unmask lists of “friends” on Facebook for users that specifically set friends’ information to private on the platform.

- Was “wasting resources, wasting time, wasting money” on IT projects, according to the then RCMP chief information officer.

- Took the names for Project Wide Awake and other internet surveillance programs from the X-Men comic book series, in which illegal government programs hunt human “mutants.”

The Tyee shared some excerpts from the files with Brenda McPhail, director of the Privacy, Technology and Surveillance Project at the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, who said they raise alarms.

“This is more evidence that we should be very concerned about this program and the incredibly secretive and unaccountable way that it was developed and run,” she said.

The Tyee first revealed in March 2019 the existence of Project Wide Awake which experts said could pose a threat to Canadians’ privacy and charter rights ![]() We don’t need to worry about RCMP/CSIS/CSEC threatening our charter rights (in my experience, RCMP violate our rights regularly, judges lie in rulings and piss on the rule of law when it suits them, and lawyers piss on the rules that “regulate” their profession), the Supreme Court of Canada already damaged our civil Charter rights in 2017, with silence from then Attorney General of Canada, Jody Wilson-Raybould

We don’t need to worry about RCMP/CSIS/CSEC threatening our charter rights (in my experience, RCMP violate our rights regularly, judges lie in rulings and piss on the rule of law when it suits them, and lawyers piss on the rules that “regulate” their profession), the Supreme Court of Canada already damaged our civil Charter rights in 2017, with silence from then Attorney General of Canada, Jody Wilson-Raybould![]() , and the same month filed a freedom of information request to the RCMP to find out more. The release of the files took a year and a half, following a complaint to the watchdog federal Office of the Information Commissioner. This is the first of more Tyee articles to come based on what we received.

, and the same month filed a freedom of information request to the RCMP to find out more. The release of the files took a year and a half, following a complaint to the watchdog federal Office of the Information Commissioner. This is the first of more Tyee articles to come based on what we received.

Hiding software purchases, claiming ‘national security’

After The Tyee exposed Project Wide Awake, the RCMP said the program employed off-the-shelf social media marketing software sold to companies and agencies for uses that merited no public concern or judicial permission.

Internally, however, the force was seeking to extend licenses on more complex monitoring software geared for law enforcement called Babel X and use it ongoing in investigations across the country. The FOI documents show this had been a goal of the force as far back as 2017.

Makers of the Babel software claim it can translate 200 languages. According to a 2017 Vice article, it has “extremely precise” filters for dates, times, data type, language and even feelings and moods expressed in messages. The article quotes a since removed passage on the company’s website boasting “the ability to evaluate sentiment in 19 languages — far exceeding the capacity of any other competitor.”

Several years before applying to secretly procure Babel X for wider purposes, the RCMP already employed it in parts of its operations, the documents released to The Tyee confirm.

The force had been using Babel X since 2016 in its Manitoba division. By 2018, the RCMP also used Babel X at its national headquarters in advance of the G7 meeting in Quebec, records including a contract confirm.

But the 2018 contract was approved for only one year for the G7 and had since expired, the RCMP told The Tyee in an October email.

In February 2019, as the force sought to secretly obtain Babel X or a tool much like it, an officer argued to Public Services and Procurement Canada that “if released into the public domain” knowledge such software was being used by the RCMP could “jeopardize border integrity” and “criminal and national security investigations,” and “provide avenues for adversaries to attempt to defeat these capabilities,” the newly released documents show.

Gilles Michaud, then commissioner of federal policing, made the argument while requesting a “national security exception” which would remove the buy from public procurement procedures.

The documents reveal the RCMP had previously obtained such exemptions for contracts related to Project Wide Awake as well as existing licenses for Babel X.

But it would appear Michaud did not get his way this time.

The force posted a public procurement notice on Nov. 29, 2019 for an unnamed “advanced social media tool,” reported on by The Tyee, and went on to quietly buy Babel X on Sept. 2, 2020.

‘A kind of trick’

Back on Dec. 28, 2016, the RCMP ordered “optional goods” — extra software and features — in a Babel X contract found in the documents, but the list was blanked out. No contract or procurement documents naming Babel X appeared on Public Services and Procurement Canada websites until 2020.

McPhail calls it “a kind of trick” the way RCMP downplayed the power of the Babel X software it was already using in some of its offices, and then sought to hide it from public scrutiny by gaining a national security exemption.

“We have a public crisis around police accountability and their use of surveillance technologies,” said McPhail. “That crisis is fed by this kind of trick — attempting to put procurement into categories that permit greater secrecy.”

Kate Robertson, a criminal defence lawyer and researcher at University of Toronto’s internet security-focused Citizen Lab agrees.

“The methods are either unexpected and therefore must remain secret, or their methods are ordinarily expected by individuals and therefore non-intrusive. The RCMP cannot have it both ways. The constitution draws a bright line: all intrusive surveillance practices by police services must be the subject of prior judicial oversight,” wrote Robertson in an email.

Private messages, political protests named ‘Darknet’ targets

In procurement forms and presentations to RCMP trainees about who it will target with its expanded tools, the RCMP lists “Darknet,” commonly understood to refer to hidden, encrypted parts of the web.

In other documents the Tactical Internet Operations Support unit names “private communications” and “political protests” in its internal definition of Darknet, which the force aimed to target. Also listed as part of Darknet are “illegal information,” “drug trafficking sites,” and “Tor-encrypted sites” which hide user identities by moving data through different servers. ![]() But Pornhub, posting videos of raping children is fine? The Children of Pornhub, Why does Canada allow this company to profit off videos of exploitation and assault?

But Pornhub, posting videos of raping children is fine? The Children of Pornhub, Why does Canada allow this company to profit off videos of exploitation and assault?

And Law Society of Ontario licencing known convicted pedophiles is fine too – keeps lawyers making plenty of money as the rest of us get raped again and again and again?![]()

But in its communication with the privacy commissioner found in the documents, the RCMP claims the targets of its monitoring are exclusively “open source,” in this case implying the tool’s purpose is to scan communications that are posted with no expectation of privacy.

“The term ‘open source’ is vague, and can obscure a wide range of sophisticated technological interferences including even hacking,” said Citizen Lab’s Robertson.

“For this reason, even open source surveillance techniques are illegal when they impact the privacy interests of individuals in Canada.”

“The surveillance technologies that are only now being revealed do not appear to be truly open source methods,” said Robertson.

McPhail added, “Our privacy commissioner has gone on the record as saying not all information in the public domain loses all reasonable expectation of privacy.”

McPhail found troubling the documents reflect an RCMP view that any communication on the internet can be assumed fair game for surveillance because it’s already in a public realm. “It’s one thing to understand that an individual will see your passing communication, and quite another thing to assume that everything you’ve ever written will be subjected to an analysis by the state.”

“It changes the relationship between the citizen to the state, and their expectations of privacy in their communications,” said McPhail.

Another RCMP email in 2017 makes reference to a separate “dark web crawler” project being led by Eric Huot, then a member of the force. Huot now runs a private internet intelligence firm, where he claims he “developed, led and managed” the RCMP’s Tactical Internet Operations Support team for over 12 years, as well as the 2018 G7 open source intelligence unit.

Huot is listed as “Operations Lead” at the TIOS team in internal documents from May 2017.

Reached by The Tyee, Huot declined to comment on RCMP projects but stated that the interception and collection of private communications, whether from Darknet or elsewhere are “not synonymous with open source intelligence activities.”

Cracking into Facebook friends

Emails in 2017 reveal the RCMP conducted a cross-province survey of software already in use for advanced social media monitoring in its divisions.

Nova Scotia RCMP responded by saying it uses a tool which can “unlock friends on private friend lists,” apparently referring to Facebook users who have set their list of friends on the platform to be hidden.

The Nova Scotia force had used software on a “covert laptop” in its investigation of organized crime and motorcycle gangs, it noted. The software also enables officers to extract entire timelines of Facebook users into Excel forms.

The force compared the tool favourably to Facebook Visualizer and Loco Citato, which perform similar functions. Loco Citato, which was also marketed to law enforcement, had been issued a cease and desist order from Facebook in 2014 for its extraction of data from the platform, according to a blog entry of its creator.

The Nova Scotia RCMP also said it used a social media scanning software named Navigator, made by Life Raft Inc., for “protest and event monitoring.”

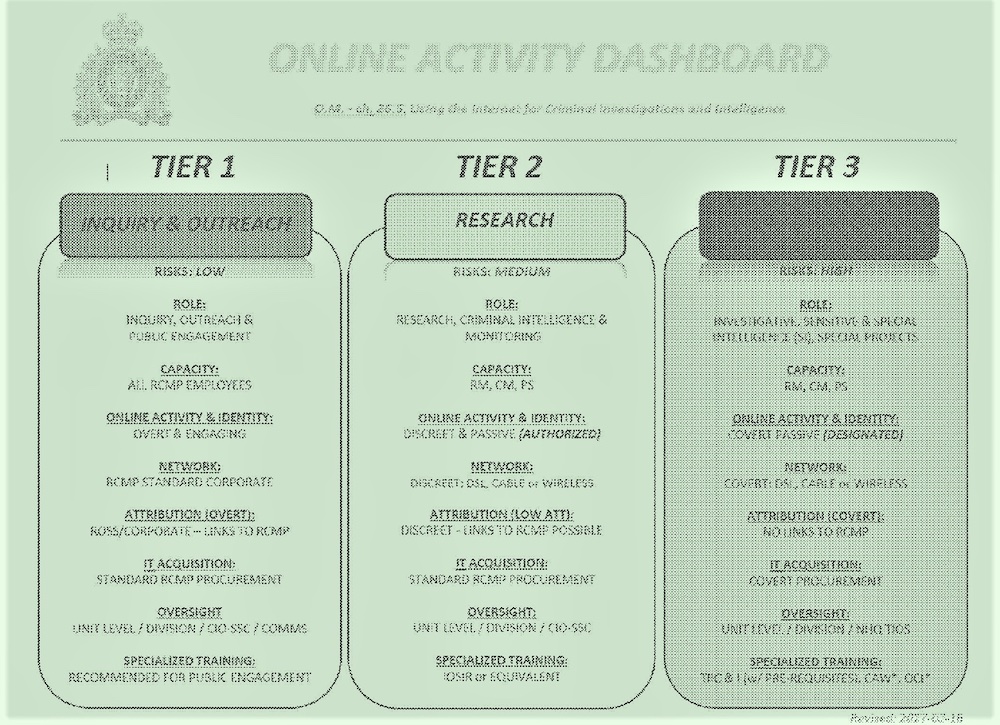

Tiers of secrecy

The documents obtained by The Tyee reveal that the RCMP’s Tactical Internet Operation Support unit codes its internal operations according to how much it wants each hidden from view.

Tier 1 operations can be visible to the public.

Tier 2 operations, described as “low attribution,” are those for which it is considered not a serious problem if they exposed.

Tier 3 operations are considered covert or undercover and involve separate clearance and clear guidelines to ensure the RCMP is not identified.

RCMP meeting notes show members discussing using technologies to enable its computers and cell phone activity to appear to originate in other countries “instead of bouncing all signals out of Ottawa.”

Heated words and a top officer exits

On Jan. 31, 2017, the RCMP discussed projects of the Tactical Internet Operations Support unit in a strategy meeting. A draft of a briefing note prepared by Tim Evans, officer in charge of Project Wide Awake for the deputy commissioner of the RCMP, suggests high tensions in-house. Pierre Perron, when a top information officer in the RCMP in 2017, blasted the RCMP’s national operations for ‘continually wasting time, wasting resources and wasting money’ and departed the force a month later to work for the Chinese IT giant Huawei.

The then chief information officer of the RCMP, Pierre Perron, entered the meeting late and “unleashed a fury of negative comments” directed at Federal Policing — the national division of the force running TIOS and Wide Awake — over its internet technology projects, said Evan’s draft, included in an email.

Federal Policing is “continually wasting time, wasting resources and wasting money and [Perron] is left to pick up the pieces,” wrote Evans in an account of Perron’s comments at the meeting dated Feb. 1, 2017. Perron would be speaking to the deputy commissioner, Evans added.

An officer whose identity is unclear commented that the wording in Evans’ draft was “highly personal” and might “inflame tensions” with Perron.

In the briefing, Evans wrote that the objective in TIOS remains to “make sure we follow the processes of the organization in order to not have another incident which caused [Perron] to express the frustration with Federal Policing.”

The unknown second officer said Evans “makes it sound like we do work to placate” Perron. And asked, “Would not the objective be to follow a process that advances Wide Awake in a legal and policy compliant manner?”

Barely a month after the meeting, Perron had departed the force and accepted a job at Huawei, according to his LinkedIn profile. The move was controversial since Perron possessed secrets about Canadian government and RCMP operations. Canada is facing pressure to ban Huawei’s attempt to develop 5G networks because of the company’s close ties to the Chinese Communist Party.

Huawei “has had a very aggressive campaign to soften its image,” Chris Parsons of Citizen Lab told the Globe and Mail a month after Perron moved to join the company. “Having a high-level Mountie might be sufficient moral suasion to alleviate some of the concerns,” Parsons added.

“I am well versed on my obligations under the Security of Information Act,” said Perron in the same Globe piece.

Reached by The Tyee via email, Perron asked to see the documents in order to comment but did not reply further after receiving them.

A police culture that draws on comic books

Project Wideawake was the name given in the X-Men comic book series to a secret, illegal government program designed to hunt down mutants — humans with special powers.

A fan website Marvel Database explains Project Wideawake “denied mutants even their most basic civil rights.”

Prior to The Tyee’s reporting on the RCMP’s web spying tools, the only online matches for the words “Project Wideawake” could be found on such X-Men fan pages.

Other covert program names at the RCMP Tactical Internet Operations Support unit borrow X-Men terminology about tracking mutants.

“It’s not uncommon for individuals who deal with dark subject matter to attempt to maintain mental equilibrium through the use of dark humour,” noted the CCLA’s McPhail. “That’s a recognized coping strategy.”

The documents make reference to TIOS aims to track organized crime and biker gangs, witness protection programs and terrorist threats.

However, she added, “It’s odd to me that our national police force would compare themselves to mutant hunters in a comic book universe. Particularly when we understand that one of the uses of this technology was to look for signs of unrest around constitutionally protected protest.”

Dark humour may inflect a slide in a presentation meant to orient RCMP members to Project Wide Awake. It declares: “You have zero privacy anyways, get over it.”

But in other moments, the force earnestly justifies its secret web surveillance by invoking a sense of overriding public duty.

“If I was to keep my community safe, I had to know who they were,” training materials for Project Wide Awake quote former RCMP commissioner Bob Paulson comparing his early career patrolling Chilliwack, B.C. to monitoring activity on the web.

Claims of serious threats intercepted

“Project Wide Awake uses commercially available software to analyze information posted on public social media platforms, work that requires no search warrant,” the RCMP told The Tyee when it first reported on the program last year.

But an exchange between a covert operations officer acknowledged in an internal RCMP exchange that Project Wide Awake is a “social media application software tool [that] could be considered surveillance by the public.”

In the same document — a form used to determine whether a privacy impact assessment should be required — the covert operations officer checked off that Project Wide Awake would not “use or disclose more personal information than in the past… collect the personal information directly from the subject individual,” or “collect personal information from other programs” from within the RCMP or “from other institutions, from other governments or from the private sector.”

The officer affirmed that Project Wide Awake data “would be used in decision-making processes that directly affect individuals.” But its collection “is specific to intelligence or investigative requirements,” the officer noted.

The internal documents obtained by The Tyee include “success stories” the RCMP cited in its proposal to obtain funding for renewal of its software licenses. Listed:

“February 2018: A request was received from C Division to see if the WideAwake tool could be used to obtain historic Twitter data from the SOC [subject of concern] relating to the Quebec Mosque shooting.”

“March 2018: The tool surfaced a tweet by an individual threatening to shoot up a high school. The TIOS team was able to determine that the individual resided in Florida.”

“March 2018: The tool surfaced a direct threat to the life of Prime Minister Trudeau. This was the Threat Assessment Unit who identified the threat using the tool.”

The RCMP has been in the process of completing a federal privacy impact assessment for over a year.

The Tyee has contacted the RCMP for comment on aspects of the released documents, including privacy protections, secrecy and how its web surveillance fits into investigations, and will include its responses in future pieces.

a few of the comments:

I’m really getting sick of ceretain parties on the federal payroll ![]() including lying judges!

including lying judges!![]() defecating on MY rights, guaranteed in OUR Constitution that is a higher law than even covert RCMP ops!

defecating on MY rights, guaranteed in OUR Constitution that is a higher law than even covert RCMP ops!

George Pope John Then get wartrants — have a 3rd party (judge) look at the application & compare it to the Constitution & stated needs. If judge approves — Tier-3 secrecy.

John George Pope Good in theory, but judges often have loose morals and looser tongues, much like senior Police (command) officers who’ve wrecked investigations.

Great investigative reporting, Bryan. This is very explosive information. I hope this story gets picked up by the national media.

What a scandal the RCMP is brewing. This confirms why I NEVER EVER reveal my real name anywhere on the internet.

***

Harsha Walia@HarshaWalia tweet dec 3, 2020:

Former RCMP analyst who hyped “violent Aboriginal extremists” was administrator of racist Facebook group.

The system is rotten and racist at its core and rcmp are an invading and occupying force on Indigenous lands. No more reforms, abolish the RCMP.

Elispogtog anti-fracking blockade had ‘violent Aboriginal extremists’ according to former RCMP intelligence analyst by Angel Moore, Dec 02, 2020, ATPN News

Tim O’Neil was also the administrator an RCMP Facebook group that contained racist comments.

A former criminal intelligence analyst for the RCMP who reported that an energy project in New Brunswick was up against “violent Aboriginal extremists” was also the administrator of a Facebook group which featured current and former Mounties, at times, making racist and disparaging remarks about Indigenous Peoples.

For six years Tim O’Neil’s duties included putting together reports for the top brass at the RCMP on issues including threats to energy projects in Canada by Indigenous groups or environmental organizations.

One of these reports, Criminal Threats to the Canadian Petroleum Industry, which is available publicly, is a criminal intelligence assessment report about the 2013 anti-fracking protests led by people in Elsipogtog First Nation near Rexton, New Brunswick.

Along with using the phrase “violent Aboriginal extremists,” O’Neil’s 2014 report also uses wording that includes “criminal intentions of the eco-extremists and violent rhetoric.

“Analysis of existing intelligence and open source reporting indicates that violent Aboriginal extremists are using the internet to recruit and incite violence and are actively engaging in direct physical confrontation with private company officials” says the report under the “Aboriginal Opposition” heading.

The peaceful protest at Rexton came to a violent end when heavily armed, militarized police raided the blockade in Kent County, N.B. on Oct. 17, 2013.

Lorraine Clair of Elsipogtog is a land and water protector who was on the ground when the RCMP moved in.

“Criminal threats to the Canadian petroleum industry,” she says reading from the report. “Criminal threats… and we were criminals now because we are defending our land, we’re protecting our water we’re you know defending our children’s and grandchildren’s inherent right, really?”

O’Neil collaborated with other policing agencies such as the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), monitoring Indigenous protestors.

“When you end up having this kind of official language that is just so biased… it really demonstrates to how rotten the institution is that it can’t recognize how problematic these things are,” says Jeffrey Monaghan, a criminology professor at Carleton University in Ottawa who has been studying RCMP tactics for more than 10 years.

O’Neil was also the administrator of a Facebook group called RCMP Mates.

As previously reported by APTN News, that site with 12,000 members, hosted racist comments aimed at Indigenous Peoples and other minority groups.

“They are out there procreating faster than smart people,” one comment read on the site says.

When members of the Wetsuwet’en Nation and their supporters in British Columbia pushed back against a pipeline, which prompted other communities to block rail lines in solidarity, the comments once again flared.

“Terrorists should be shot, this goes way beyond reasonable protest,” said one post. “It’s so funny, they still call them protestors, they are domestic terrorists.”

None of these comments are attributed to O’Neil.

But he resigned from the group after APTN contacted him regarding the group and published a story on Aug. 31.

Before resigning, he had a warning for members of the group.

“I want to alert the group that I was contacted by APTN… remove any posts that were even the least bit controversial,” he wrote.

O’Neil also had a message for his followers in the Facebook group.

“Threatening to go to the media will end with your immediate removal.”

APTN reached out to O’Neil several times for an interview.

He declined, stating that, “as a former RCMP employee I am by law not permitted to discuss my work while employed with the RCMP.”

But that statement to APTN on Nov. 24, 2020 seems to be contradicted by what O’Neil posted on RCMP Mates and his LinkedIn profile.

“Between 2008 and 2014, I was the RCMP’s lead criminal intelligence analyst tasked with identifying and analyzing potential and credible threats to the Canadian energy sector,” he wrote.

The RCMP confirmed in an email to APTN, O’Neil worked on the critical infrastructure team from 2008 to 2012.

Monaghan says reports like O’Neil’s only promote one side of the issues – and it’s not the Indigenous side.

“I think there’s just so much on the ground racism, outright racism where RCMP officers are treating Indigenous people like crap,” he says.

Clair remembers being arrested weeks after the RCMP’s takedown of the anti-fracking blockade.

“This guy is smearing pretty well every Aboriginal movement that has occurred to defend land, water and what do you call it, treaty rights they are not even stating this is why we are doing it you know we are defending our rights, if the tables were turned, if we were infringing on their rights, you know, would they not stand up too?”

Monaghan says O’Neil criminalized Indigenous protectors as eco-terrorists. ![]() AER did same to me, after I sent them evidence of Encana/Ovintiv breaking the law. First though, in 2005, AER ruled me a criminal (in writing), without any evidence, no hearing or trial, no arrests, no fingerprinting, no charges, all without letting me know I was being judged and given no chance to hire a lawyer during their secret process. Seven years later, they changed their “criminal” ruling to me being an “eco-terrorist” in an official court filing, again without any evidence, no hearing, no trial, no arrest, no fingerprinting, no charges. The Supreme Court of Canada recently ruled even those that harm others have charter rights that must be protected, but RCMP, AER, Alberta courts and the Supreme Court of Canada do not protect Charter rights of civil Canadians that have not caused harm to others and have been harmed by the oil and gas industry.

AER did same to me, after I sent them evidence of Encana/Ovintiv breaking the law. First though, in 2005, AER ruled me a criminal (in writing), without any evidence, no hearing or trial, no arrests, no fingerprinting, no charges, all without letting me know I was being judged and given no chance to hire a lawyer during their secret process. Seven years later, they changed their “criminal” ruling to me being an “eco-terrorist” in an official court filing, again without any evidence, no hearing, no trial, no arrest, no fingerprinting, no charges. The Supreme Court of Canada recently ruled even those that harm others have charter rights that must be protected, but RCMP, AER, Alberta courts and the Supreme Court of Canada do not protect Charter rights of civil Canadians that have not caused harm to others and have been harmed by the oil and gas industry.![]()

Above slide from Ernst presentations

“And for policing Indigenous protests in particular it was really kind of sensationalizing the threat in a way that I think was trying to really kind of put Indigenous protests on to the like kind of a higher level of threat to get more resources within the policing bureaucracy.”

Monaghan isn’t the only one raising concerns about reports like the one compiled by O’Neil.

A recent report by former Supreme Court justice Michel Bastarache found the culture at the RCMP “toxic.” And that the force tolerates misogyny, homophobia and racism.

The Civilian Review and Complaints Commission issued a report in November after a seven year long investigation into the RCMP takedown of the Mi’kmaw anti-fracking blockade, that justified the Mounties’ militarized use of force and found the RCMP did not display bias towards Indigenous people.

***

RCMP civilian oversight agency has ‘no teeth’ and is ‘fundamentally flawed’ say lawyers, Review and Complaints Commission has powers of investigation it rarely uses by Thomas Rohner, CBC News, Jul 02, 2020

The agency charged with oversight of the RCMP, including across the North, is not only decades behind the national trend but rarely employs what limited powers it is legislated to use, according to some experts.

The Civilian Review and Complaints Commission (CRCC) for the RCMP provides oversight of complaints against the Mounties across Canada. But it can also conduct its own investigations and order its own hearings, according to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act, which created the commission.

“They have the power to conduct investigations, they have the power to hold a public inquiry into a complaint, but they don’t do it,” said Tom Engel, a criminal defence lawyer from Edmonton.

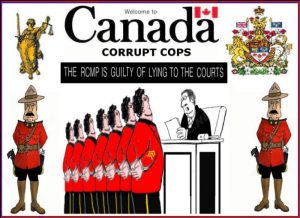

“It’s actually a disgraceful process. They keep saying they have independent oversight, which is completely false,” he said.

Complaints against the RCMP are usually investigated by the RCMP themselves, according to the RCMP act.

Experts have been saying for years that police investigating police is not best practice because police often protect other police, even from other agencies.

After the RCMP investigates a complaint, if the complainant is unhappy with that investigation, they can request the complaints commission to review the file.

The commission can then send the file back to the RCMP and ask for further investigating.

Over the last three years, the commission received more than 7,000 complaints, commission spokesperson Kate McDerby told CBC.

Of those complaints, 795 complainants asked for a review, McDerby said.

Eighteen of those files were sent back to the RCMP for further investigation.

Six Nunavummiut asked for a review of their investigation, but McDerby said none of those were sent back for further investigation.

Long delays

Engel said he recently received a report from the commission on a complaint for which he requested a review — more three years ago.

“When you go to the CRCC to review the dismissal of a complaint, you don’t get the investigative file. You don’t get to see how the investigation was conducted,” said Engel.

The report was also sent to the RCMP chief, as per the commission’s process.

“Then it’ll be the commissioner doing a response in another year or year and a half. And the commissioner can just say, ‘I don’t agree.’ So there’s no teeth in the CRCC,” Engel said.

The national trend in police oversight is to have civilian-led investigations because police investigating police do not have the public’s confidence, other experts told CBC.

The CRCC’s predecessor, the Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP, was created by parliament in 1988.

In 2013, additional accountability measures were enacted, and the commission changed its name to emphasize civilian involvement in the process. But that involvement is usually limited to the review of investigations done by police — not in the investigation itself.

Powers rarely used

There are some sections of the RCMP act that give the commission more powers.

For example, if the commission is not satisfied with the RCMP commissioner’s response to a complaint review, the commission can call a hearing.

That has not been done in the past five years, according to commission spokesperson McDerby.

The commission can also decide to hold a hearing into a complaint review if it decides it would be in the public’s interest.

That also hasn’t happened in the past five years, said McDerby.

The commission has conducted 23 public interest investigations over the past five years but none since 2017, McDerby said.

Those investigations are conducted by staff “with a combination of administrative investigations and policing background.”

The chair of the commission can initiate investigations under a different section of the act.

McDerby said that has occurred four times in the last five years —three times in 2016 and once in 2018.

Complaints commissioner says RCMP sitting on year-old report into alleged abuses of power

RCMP watchdog’s misconduct reports caught in limbo, stalling their release

‘Fundamentally flawed’

The commission does not provide effective civilian oversight of the RCMP, said Benson Cowan, head of Nunavut’s legal aid.

“All it is, is some sort of oversight over internal discipline … It’s fundamentally flawed as a model for civilian oversight,” Cowan said.

Cowan said he questions whether the commission has the mandate, political will or adequate funding to pursue its own investigations.

“Their mandate makes it very clear, if there’s any systematic review, it can’t come at the expense of the other operations … so it’s zero sum for them in terms of the envelope of funding,” said Cowan.

The commission did not respond to a request for comment in response to Engel’s and Cowan’s remarks.

Cowan has asked the commission to conduct a systematic review of policing across Nunavut.

He sent two letters over the past year highlighting more than 30 cases that include allegations from Inuit of police violence, racism and misconduct.

The commission has not yet announced a decision.

RCMP surveillance, searches breached anti-fracking protesters’ rights: watchdog says by Jim Bronskill, The Canadian Press, Nov 12, 2020

OTTAWA — The RCMP watchdog has uncovered shortcomings with the national force’s crowd-control measures, physical searches and collection of social media information while policing anti-fracking protests in New Brunswick.

In a long-awaited report issued today, the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP chastises the Mounties for their reluctance to take action on some of the findings and recommendations.

The commission received 21 public complaints related to the RCMP’s management of protests in 2013 over shale-gas exploration by SWN Resources Canada near the town of Rexton and the Elsipogtog First Nation reserve in Kent County, as well as in various other parts of the province.

Full report into RCMP response [Copied also below to archive it.]

The report notes that a primary motivation for Indigenous protesters opposing the actions of SWN was their dedication to protecting land and water they considered their own, unceded to the Crown through treaty or other agreement.

A court-issued injunction limited protests and despite some progress through negotiations between the RCMP and demonstrators, the Mounties cleared an encampment on Oct. 17, 2013, sparking a melee and numerous arrests.

After reviewing the complaints and materials disclosed by the RCMP, the commission then initiated its own investigation in December 2014 to examine the issues more broadly.

The commission found considerable evidence that RCMP members “understood and applied a measured approach” in planning their operations and while interacting with protesters.

However, it also found some distressing problems.

“Several incidents or practices interfered to varying degrees with the protesters’ rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly,” the commission concluded.

It stressed that police may only establish “buffer zones” within parameters set by the courts. “As such, decisions to restrict access to public roadways or sites must be specific, reasonable and limited to minimize the impact on people’s rights.”

The commission also found that some of the RCMP’s surveillance practices and physical searches were “inconsistent with protesters’ charter rights to be free from unreasonable search and seizure.”

For example, in conducting “stop checks,” RCMP members randomly stopped vehicles for a purpose other than those set out in provincial highway traffic legislation, the report says.

“Likewise, while unconfirmed reports about the presence of weapons raised a legitimate public safety concern, searching persons entering the protesters’ campsite was inconsistent with the individuals’ charter rights.”

The commission found that RCMP policy did not provide clear guidance on handling personal information obtained from social media or other open sources, particularly in situations where no criminal activity was involved.

The watchdog recommended that RCMP policy describe what personal information from social media sites can be gathered, how it can be used, what steps should be taken to verify its reliability and limits on how long it can be kept.

It urges the RCMP to destroy such material once it is clear there is no criminal or national-security dimension.

Among the commission’s other findings:

– The RCMP’s interactions with SWN Resources were reasonable under the circumstances, and enforcing the law and injunctions did not amount to acting as private security for the company, as some had claimed;

– RCMP members did not differentiate between Indigenous and non-Indigenous protesters when making arrests, nor did they demonstrate bias against Indigenous protesters generally;

– Officers had reasonable grounds to arrest people for offences including mischief and obstruction, and the force used was generally necessary and proportional;

– The Mounties had legal authority to clear the campsite and it was a “reasonable exercise of their discretion” to do so, though it would have been prudent to allow more time for negotiations;

– The decision to leave members of the crisis negotiation team out of the loop about operational planning led to the “unfortunate and regrettable situation” of the tactical operation occurring shortly after RCMP negotiators offered tobacco to campsite protest leaders;

– At the time the policing efforts began, with some notable exceptions, assigned members did not have sufficient training in Indigenous cultural matters.

“Canada’s ongoing reconciliation with Indigenous people includes protecting the rights of those whose voices have been diminished by systemic sources of racism in our society,” commission chairwoman Michelaine Lahaie said in a statement accompanying the report.

In her response to the report, RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki agreed to implement recommendations on sensitivity and awareness training related to Indigenous culture and sacred items, better information-sharing with crisis negotiators and refreshers for RCMP members on law and policy for search and seizure.

But while the RCMP indicated support for eight of the commission’s 12 recommendations, it believed three needed no further action.

“This concerns the commission, as these included recommendations concerning roadblocks, exclusion zones and limits to police powers,” the report says.

Lucki also strongly rejected recommendations limiting collection and retention of open-source information, saying the RCMP must have ready access to data about protesters, even if they have no criminal history.

The RCMP’s right to refuse to implement findings or recommendations, and its statutory obligation to explain itself when it does so, is not meant to provide an opportunity for the police force to act as an appeal body with regard to the commission’s findings, the report says.

“Such a process would amount to giving the RCMP carte blanche to come to its own conclusions about its members’ actions.”

Earlier this week, a civil liberties group launched a court action to force the release of a complaints commission report on alleged RCMP

of anti-oil protesters in British Columbia

The B.C. Civil Liberties Association says the Mounties have been sitting on an interim report for more than three years and the group is now asking the Federal Court to order Lucki to finalize her input so the watchdog can release it.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 12, 2020.

Mounties may have broken law during N.B. anti-fracking protests, says watchdog, CRCC concerned about RCMP commissioner’s response to recommendations by Catharine Tunney, CBC News, Nov 12, 2020

Some RCMP tactics during the 2013 anti-shale gas protests in New Brunswick may have broken the law, while other practices raise concerns about how Mounties conduct surveillance on protesters, according to an investigation by the force’s watchdog.

The Civilian Review and Complaints Commission released its final report this morning on how the RCMP responded to anti-fracking protests that erupted into a riot in the fall of 2013 near Elsipogtog First Nation in Kent County, N.B.

While the 200-plus-page report notes many officers acted reasonably, it flags deep-seated concerns with the way Mounties gather intelligence, restrict individuals’ movement during protests and approach Indigenous culture.

“In relation to police roadblocks and stop checks and the collection of open-source intelligence, the commission has expressed concerns about the reasonableness and, at times, the legality of the practices engaged in by the RCMP,” says the commission’s final report, released Thursday morning.

The protests at the heart of the investigation began after the government of New Brunswick granted a licence to SWN Resources Canada to explore the accessibility of shale gas near the town of Rexton. The protesters — many of them Indigenous and fiercely opposed to the exploration project — retaliated by blocking access to the site and setting up an encampment.

Release report into RCMP conduct during Rexton protests, says anti-shale gas group

Police were in the area to enforce a court-issued injunction. Tensions boiled over after the Mounties ran a tactical operation on Oct. 17 and cleared the site. The clash resulted in what the commission described as a riot, leading to dozens of arrests and multiple RCMP vehicles being torched.

After receiving more than 21 complaints, the commission launched an investigation that looked at the six-month span from June to December 2013. As part of the probe, the CRCC reviewed thousands of files, video and documentary evidence and spoke to more than 100 witnesses. ![]() With no authority reviewing Harper’s Supreme Court of Canada intentionally publishing a lie in their ruling in Ernst vs AER (7/9 of the judges were appointed by the Harper Klan), and “justice” and “environmental” lawyers silent on the matter, including my own, after paying them hundreds of thousands of dollars of my life-long savings. My lawyers even refused me ccing them on my letter of concern to the Canadian Judicial Council, which of course rendered my letter useless, except for paper trail.

With no authority reviewing Harper’s Supreme Court of Canada intentionally publishing a lie in their ruling in Ernst vs AER (7/9 of the judges were appointed by the Harper Klan), and “justice” and “environmental” lawyers silent on the matter, including my own, after paying them hundreds of thousands of dollars of my life-long savings. My lawyers even refused me ccing them on my letter of concern to the Canadian Judicial Council, which of course rendered my letter useless, except for paper trail.![]()

RCMP didn’t have legal authority: report

That investigation concluded that some of the RCMP’s surveillance practices and physical searches were inconsistent with protesters’ Charter rights. ![]() Since Harper appointed many to the board of the CBC, their reporting has mostly gone to shit. Why not state Charter rights were violated by the RCMP? Were my Charter rights violated when Harper’s anti-terrorist squad invaded my private property, and tried to terrify me silent?

Since Harper appointed many to the board of the CBC, their reporting has mostly gone to shit. Why not state Charter rights were violated by the RCMP? Were my Charter rights violated when Harper’s anti-terrorist squad invaded my private property, and tried to terrify me silent?![]()

“It appears that RCMP members did not have judicial authorization, or other legal authority, for conducting stop checks for the purposes of information gathering in a way that constituted a ‘general inquisition’ into the occupants of the vehicles,” notes the report.

“This practice was inconsistent with the Charter rights of the vehicle occupants.”

The information gathered by RCMP officers included drivers’ names, dates of birth, addresses and licence numbers, and other distinguishing features such as height, weight, facial hair, race and hair colour. One section of the intake form used by RCMP officers to collect the information leaves room to describe where the driver had been “observed” and whether a criminal record or police database check had been conducted on the driver.

“In conducting ‘stop checks,’ RCMP members randomly stopped vehicles for a purpose other than those set out in provincial highway traffic legislation,” said the report.

“The members were not responding to an emergency, nor did they have judicial authorization to do so.“

The commission also concluded that the practice of searching people entering the campsite was not consistent with their right to be secure against unreasonable search and seizure.

Given those findings, the commission said Mounties involved in such public order policing operations should undergo a refresher on the laws and policy on search and seizure, including warrant requirements. ![]() Which will do little, if any, good and enable the abusive RCMP law violations, racism, raping and bullying to escalate.

Which will do little, if any, good and enable the abusive RCMP law violations, racism, raping and bullying to escalate.![]()

RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki disagreed.

Watchdog memos show RCMP was slow in turning over 2013 Mi’kmaw demonstration documents

Civil liberties group takes RCMP to court over delayed response to alleged spying complaint

She argued that, according to her reading of the evidence, there was nothing to conclude that the sole purpose of the stop checks was intelligence gathering and said there weren’t enough facts or context to form those conclusions. She also noted that some of the video evidence showed only snippets and not the entire interactions.

“In determining whether the search of the vehicles entering the campsite was reasonable, I must consider all the circumstances, specifically in this case the environment in which the searches were conducted,” said Lucki.

“Obviously, the anti-shale gas protests at times created an extremely hostile environment.”

Lucki wrote in her 19-page response, however, that while she disagrees with the recommendation, she offer a review of the relevant laws to RCMP officers “as a best practice going forward.”

Intelligence gathering online questioned

The commission also looked into how the Mounties kept an eye on protesters and how that intelligence was stored.

The report found that RCMP policy did not provide clear guidance on collecting, using and retaining personal information obtained from social media and other open sources — especially in cases where those involved had no criminal involvement or intention.

“For example, the commission found that any gathering of potentially private electronic communications by the RCMP must be done only within the strictures of the law,” it said. ![]() Pffft, as if the RCMP give a damn about Canada’s “rule of law” or those of us harmed by law-violating oil and gas companies or their enabling, law-violating “regulators.” Refer below to tweet by Edmonton lawyer Avnish Nanda.

Pffft, as if the RCMP give a damn about Canada’s “rule of law” or those of us harmed by law-violating oil and gas companies or their enabling, law-violating “regulators.” Refer below to tweet by Edmonton lawyer Avnish Nanda.![]()

The commission recommended that the RCMP provide clear policy guidance on collecting and storing personal information from open sources, such as social media, and that steps should be taken to ensure its reliability.

Shale gas protesters react in disbelief to watchdog findings

RCMP watchdog’s misconduct reports caught in limbo, stalling their release

In her response, Lucki acknowledged that when the protests were happening, the RCMP did not have a policy that provided clear guidance on gathering personal information obtained from social media or other open sources. She said the RCMP has since made some changes.

But she disagreed with the recommendation to update the policy on intelligence gathering and storage. Lucki said that the RCMP will use tactical intelligence to obtain information about groups involved in public protests to determine whether they pose any risk to participants.

“The police have a duty to prevent crime and keep the peace, but they also have a general duty to protect life and property that extends beyond crime prevention and peacekeeping functions,” wrote Lucki.

“The RCMP needs to have the ability to access information on the participants even in situations where there is no reason to believe that the participants were previously involved in criminal activities.”

In its final report, the watchdog wrote that it’s troubled by the RCMP’s response and said it has ramifications for public protests going forward.

“The RCMP’s position on the indiscriminate, long-term retention of personal information about lawful dissent collected from sources like social media is concerning,” said the report.

“This raises at least the potential for a chilling effect regarding the public’s participation in lawful dissent and in online discussions, particularly through social media.”

Indigenous sensitivities

The commission also found that RCMP members assigned to the operation did not have sufficient training in Indigenous cultural matters.

However, it said based on the available evidence, it is satisfied that officers did not differentiate between Indigenous and non-Indigenous protesters when making arrests.

The commission made multiple recommendations related to training on Indigenous cultural practices and the handing of sacred items. The RCMP said it will implement those recommendations.

“Since the Kent County anti-shale gas protests, the RCMP has deployed ongoing efforts on training current and new members to keep pace with the diversity, understanding, and compassion required to execute policing duties in a bias-free manner and to provide members with a solid knowledge of cultural elements and history of our Indigenous communities,” wrote Lucki.

The report cleared officers on many fronts, concluding that the RCMP’s use of force was generally necessary and proportional in the circumstances, especially given the risks posed by the protesters’ conduct. ![]() In my view of the events, the commission got that backwards. It was the heavily harmed snipers/RCMP conduct that escalated tensions and risks, I expect on orders from Oil-Patch-Harper to feed his rabid racist base and terrify Canadians concerned about and protesting frac’ing into silence.

In my view of the events, the commission got that backwards. It was the heavily harmed snipers/RCMP conduct that escalated tensions and risks, I expect on orders from Oil-Patch-Harper to feed his rabid racist base and terrify Canadians concerned about and protesting frac’ing into silence.![]()

However, it said it did say the plastic tie handcuffs placed on some protesters’ wrists likely were tighter than necessary.

Issues with review legislation

The commission released portions of its interim report earlier this year when it was asked to review the RCMP’s conduct on Wet’suwet’en traditional territory in British Columbia.

CRCC chairperson Michelaine Lahaie declined to launch a public interest investigation because she said the same broad issues were raised and previously investigated in New Brunswick.

The Civilian Review and Complaints Commission reviews thousands of complaints every year, though the vast majority are not as high-profile as the Rexton protests.

RCMP civilian oversight agency has ‘no teeth’ and is ‘fundamentally flawed’ say lawyers

Average wait for RCMP response to misconduct reviews is growing: report

While the commission has investigative powers and can make recommendations, the RCMP is under no obligation to implement those findings — and there’s no appeal process to deal with disagreements between the two bodies.

This is something the report called into question multiple times.

“The RCMP’s own views about the appropriateness of its members’ actions should not be allowed to govern in a case where the independent oversight body, having examined all the evidence as it is mandated to do, has reached a different conclusion, and no further factual information or explanation is being offered by the RCMP,” the report concludes.

“Such a process would amount to giving the RCMP carte blanche to come to its own conclusions about its members’ actions.”

Watchdog reported on RCMP surveillance of Indigenous-led action in 2017. Mounties never responded by Mike De Souza, Global News, July 10, 2020

Jasmine Thomas can provide a simple description of how her community started forming new alliances nearly a decade ago.

“Most of our matriarchs (were) sitting in a home, talking around a kitchen table and planning future community meetings and community engagement,” said Thomas, a councillor of the Saik’uz First Nation.

Members of her First Nation helped organize public rallies and events to raise awareness about issues such as resource development, human rights, climate change and sovereignty over their territory, she explained.

But what they didn’t know at the time was how closely Canada’s national police force was tracking what they were doing in private.

RCMP have yet to respond to 3-year-old watchdog report into Mounties surveillance of Indigenous-led action

The RCMP produced an intelligence report about the activities of the Yinka Dene Alliance, a coalition of six nations, including the Saik’uz, which is located in central British Columbia about 100 kilometres west of Prince George.

In a copy of that report, released through access-to-information legislation, the police force provided a description of a private meeting at a community hall organized by Indigenous leaders. At the time, details of that meeting were not public.

“On Nov. 25th, 2011, a meeting was held at Nadleh Whut’en (Fraser Lake) between the YINKA DENE ALLIANCE (YDA), and various environmental groups,” read the intelligence report. “The purpose of the meeting was to strengthen the alliance between First Nations and environmental groups opposing ENBRIDGE.”

The Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline project was ultimately rejected by the federal government in November 2016, a few months after the Federal Court of Appeal concluded that the Crown had failed to adequately consult First Nations affected by the project.

But Thomas said the monitoring activity has left scars and a legacy of mental health issues on the targeted Indigenous communities who felt intimidated by the RCMP’s actions.

![]() It’s impossible for me to describe the stresses and terror caused to me (and for my loved ones) after the RCMP invaded my private property to serve aquifer frac’er Encana/Ovintiv and our pathetic regulators. I have not yet recovered, and expect I never will. Cumulatively add the stress of my lawyers directing me not to file an official complaint about the RCMP invasion when I told them I was going to – which made no sense to me at the time, but since they quit, now does, including their misrepresentations, ignoring my correspondence, withholding my website nearly a year and my trust account funds a year, and prejudicing my case by still withholding my case file two and a half years after quitting (all contrary to their “regulator” rules).

It’s impossible for me to describe the stresses and terror caused to me (and for my loved ones) after the RCMP invaded my private property to serve aquifer frac’er Encana/Ovintiv and our pathetic regulators. I have not yet recovered, and expect I never will. Cumulatively add the stress of my lawyers directing me not to file an official complaint about the RCMP invasion when I told them I was going to – which made no sense to me at the time, but since they quit, now does, including their misrepresentations, ignoring my correspondence, withholding my website nearly a year and my trust account funds a year, and prejudicing my case by still withholding my case file two and a half years after quitting (all contrary to their “regulator” rules).