Of course Canada’s genocidal racist courts do this.

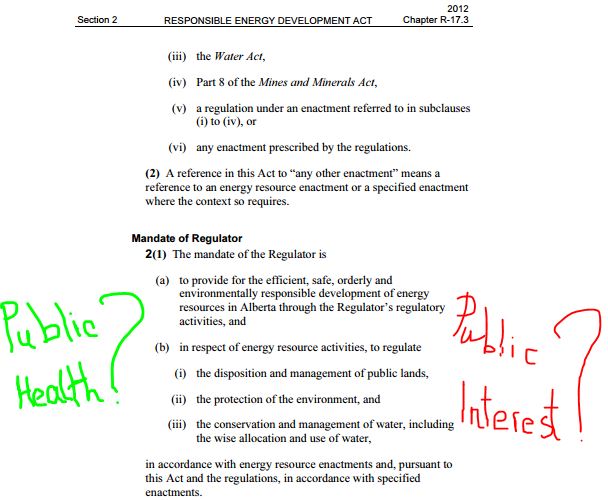

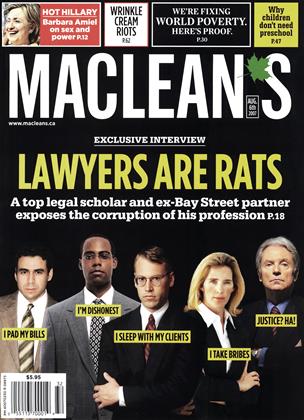

What happens in the Wild Wild White Raping West now that public interest has been removed from our energy (de)regulators’ mandates? Alberta removed public interest from AER’s mandate after my lawsuit went public, yet lies about that, often. Even AER’s outside counsel Glenn Solomon of JSS, Calgary law firm, lied about it at the Supreme Court of Canada in the Ernst vs AER hearing. Lawyers lie, a lot, so do judges, to keep Canada’s resource rape and pillage going strong.

British Columbia recently copied Alberta’s deregulation by removing the OGC’s mandate to operate in the public interest, and copying AER’s name, to BC Energy Regulator.![]()

![]() Racist rat lawyers are made racist rat judges by racist old white man rats in politics.

Racist rat lawyers are made racist rat judges by racist old white man rats in politics.![]()

***

Shiri Pasternak@shiripasternak arch 1, 2023:

In this new paper, @irinaceric & I set out to answer a simple q: why are injunctions often won by corporations against First Nations? Examining 70 cases, we found that Indigenous rights are sacrificed by courts for the “public interest”: to protect boom & bust resource economies.

“We conclude that the heavy lifting done by notions of ‘public interest’ both relies on and obscures the … exclusion of Aboriginal treaty and constitutional rights from the law of injunctions and constitutes a de facto resolution of Aboriginal land rights in Canada.”

@irinaceric March 1, 2023:

Several years in the making, “‘The Legal Billy Club’: First Nations, #Injunctions, and the Public Interest” by @shiripasternak & me is now out in the world. Look for it soon in the inaugural issue of the @LincAlexLawTMU Law Review or check it out on SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf

We take a deep dive into 70 cases involving First Nations to try and figure out why corporations and governments are so successful in obtaining injunctions. Spoiler: it was the political economy of settler-colonial law all along.

***

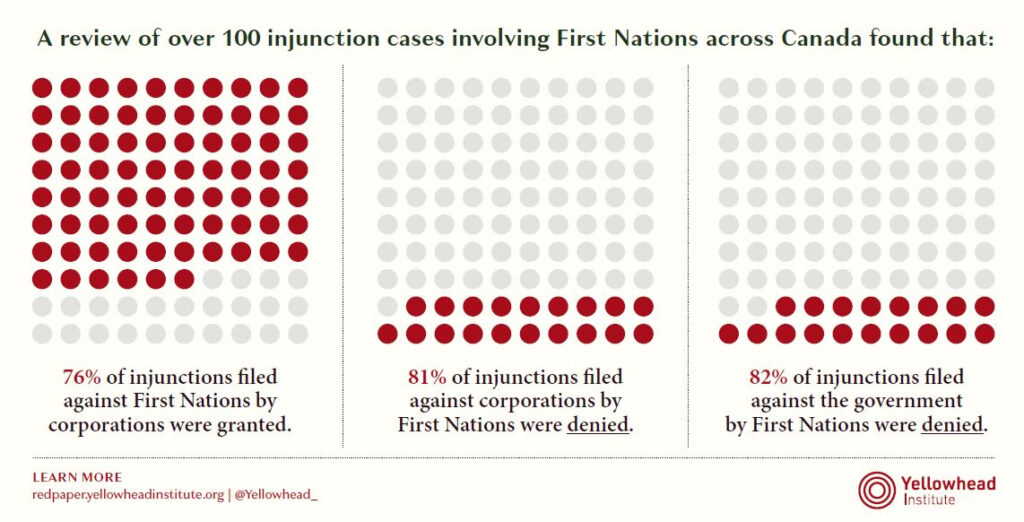

Review of over 100 injunction cases involving First Nations across Canada in Yellowhead Institute’s 2019 report Land Back:

76% of injunctions filed against FN by private corporations were granted;

81% of injunctions filed by FN against corporations were denied;

82% of injunctions filed against the gov’t by FN were denied.

2019 report Landback by Yellowhead Institute Report Overview

‘The Legal Billy Club’: First Nations, Injunctions, and the Public Interest by Shiri Pasternak and Irina Ceric, February 24, 2023, TMU Law Review, Forthcoming, SSRN, March 1, 2023

![]() During my read of this report, I removed the footnote numbers. To read the entire report, complete with footnotes and numbers, go to link for the report.

During my read of this report, I removed the footnote numbers. To read the entire report, complete with footnotes and numbers, go to link for the report.![]()

Abstract

This article centers on the profound discrepancy between efforts by First Nations to obtain injunctions against industry and the state versus the far more successful record of corporations and governments seeking to obtain injunctions against First Nations. We examine how the common law test for injunctions in struggles over lands and resources leads to these results. We begin with the history of injunctions in the Aboriginal law context, especially the development of s. 35(1) jurisprudence which ironically deprived First Nations of access to injunctions, despite an earlier period of successful defence of Indigenous land rights using this legal tool. We then focus on the doctrinal and political function of the “public interest” consideration in injunction cases, locating this concept within a broader political economy framework. Finally, we turn to the origins of the injunction as an equitable remedy and argue that the current imbalance in injunction success rates ought to be understood though a re-examination of equity within a broader historical trajectory of settler-colonial legality. We conclude that the heavy lifting done by notions of ‘public interest’ both relies on and obscures the circumvention and exclusion of Aboriginal treaty and constitutional rights from the law of injunctions and constitutes a de facto resolution of Aboriginal land rights in Canada. Finally, we ask what place, if any, exists in injunction jurisprudence for Indigenous law and governance.

…

This paper begins with a simple question: what accounts for the profound discrepancy between the efforts by First Nations to obtain injunctions against corporations and governments, versus the efforts by corporations and governments to obtain injunctions against First Nations? In 2019, a national study of over 100 injunctions was led by the Yellowhead Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University in Toronto. It found that from the years 1973-2019, 76 percent of injunctions filed against First Nations by corporations were granted, while First Nations were successful against corporations only 19 percent of the time. This research was updated by Yellowhead in 2020 and the gap had widened in that single year. The percentage of injunctions successfully sought by corporations against First Nations climbed from 76 to 81. The study also examined rates of government-filed injunctions against First Nations. In 2020, governments were successful at obtaining orders 90 percent of the time. Just one year earlier, that figure had been 86 percent. Meanwhile, by 2020 First Nations were only successful at obtaining injunctions against governments 18 percent of the time. In this paper, we ask: what is it about the common law test for injunctions that leads to these results, and given this evidence, what makes injunctions such an effective tool in the hands of industry and the state against First Nations?

…

This paper undertakes a close reading of the way the courts interpret the RJR-MacDonald factors of “irreparable harm” and “balance of convenience” in injunction cases involving First Nations – most of which have unfolded in contestations over land, water, and resources – to reveal the ways colonization has been organized around a false distinction between public and private interests. We suggest that to understand what accounts for the significant difference in corporate success in the courts against First Nations when seeking to develop and pursue extraction on Indigenous territories, we must understand how “public interest” arguments that are critical to applying the injunction test are weighed towards a specific understanding of the “status quo” in Canada that is rooted in a political economy of resource extraction.

We argue that to understand the judicial reasoning that supports the “maintenance of the status quo” that is so critical to the “balance of convenience” test, we must revisit the equitable roots of the injunction remedy that lie at the heart of Canadian property law — the juridical underpinning of settler colonialism.

…

We conclude that the injunction playing field is inherently uneven because the common law test currently leaves no room for assertions of Indigenous law or governance. This imbalance is now baked into RJR-Macdonald and a juridical shift (as opposed to a political or policy fix) requires a different legal framework.

2. The strange power of uncertainty & the impact of s. 35(1) on injunctions

In the early 2000s, John Hunter analyzed the trajectory in the use of injunctions by First Nations in British Columbia [BC]. Interlocutory injunctions had been “the primary remedy in Aboriginal rights litigation” in the province between 1985 and May 1990 and Hunter demonstrated how they were obtained or fought by First Nations relatively successfully to defend their lands, as courts found against private interests in their favour.

He argued, however, that when the SCC issued its landmark ruling in R. v. Sparrow, things began to shift.

Sparrow was the first SCC case to interpret s. 35(1) of the new Constitution Act, which “recognized and affirmed” Indigenous peoples “aboriginal and treaty rights.” Sparrow and the cases that followed began to lay out the tests that define the scope and meaning of Aboriginal rights. Hunter argued that it was precisely the evolution of this new constitutional landscape that led judges to shift their understanding of what constituted a “balance of convenience” away from First Nations and in favour of companies, arresting the short winning streak Indigenous claimants had enjoyed in the late 1980s. How is it possible that when it came to injunctions, an ostensible expansion of Aboriginal rights jurisprudence swayed courts against First Nations?

…

With the incorporation of Aboriginal rights in the constitution, the declining success of First

Nations in obtaining or fighting injunctions appears to be a contradictory outcome at a key moment of recognition. At first glance, this recognition should have strengthened Aboriginal claims of “irreparable harm,” as such harms could now constitute a breach of constitutional rights. But Hunter argued that these new constitutional protections greatly complicated – and therefore lengthened – the duration of time necessary to determine the merits of a case, giving priority to other elements of the injunction test. First Nations were asserting rights and title to land in ways that disrupted, for example, provincial regulatory regimes; a growing jurisprudence established tests to challenge the application of provincial jurisdiction to First Nations. But how would these Aboriginal rights tests weigh within the tripartite test?

First, the lengthening of trials specifically increased the inconvenience to business operations, therefore favouring their interests in the “balance of convenience” test. For a time, the uncertainty of title and rights claims had constituted sufficient cause to delay the interests of private companies; post Sparrow, the uncertainty had a legal framework for determination that was lengthy, complicated, and lay outside the jurisdiction of the court hearing the injunction application. Compounding the issue of the time it would take to adjudicate the merits of injunction cases was the gradual emptying out of the s. 35(1) “box” of rights, once expected to secure Aboriginal rights to land, water, and resources. The s. 35(1) case law demonstrated that there were pathways around these rights and that state legislation could override Aboriginal claims. The

uncertainty that once favoured First Nations asserting constitutional rights in injunction cases18 was now taken up by courts that pointed to the ambivalence of rights that were yet to be proven in costly title and rights litigation.

A 1995 Gitskan injunction case – technically, a leave to appeal their denial of on-going injunctive relief – is emblematic of this transition period. The landmark Delgamuukw v. British Columbia19 case brought by the Wet’suwet’en and Gitskan Nations that first tested s. 35(1) rights on Aboriginal title was a factor in the judge’s decision against two Gitskan houses.20 The houses sought relief against Skeena Cellulose to restrain bridge construction that the company required for logging access. Proudfoot J.A. agreed with a lower court decision to discharge an injunction granted in 1988 to the Houses of Gwoimt and Tsabux. She held that the injunction had been founded on outstanding questions of Aboriginal title, but that the legal terrain had changed after the 1993 BC Court of Appeal decision in Delgamuukw22 that found that no ownership or jurisdiction rights had been established by the Gitskan. A few years later, in 1997, the SCC held that the Wet’suwet’en and Gitskan Nations might in fact hold Aboriginal title to their territory, defined for the first time as an underlying, collective, and sui generis proprietary interest. The SCC instructed the nations to return to court to assert this title over specific tracts of land. But while the Gitskan were undertaking this monumental, lengthy title case, lower court decisions had cost them interim protections, raising serious questions about the implications of injunctions on First Nations’ constitutional rights.

One solution to this problem of reconciling rights and title cases with injunctions came in the form of another s. 35(1) precedent, conceived to protect Aboriginal rights even in the pre-proof stage of assertion: the Crown’s duty to consult and accommodate. In the post-Sparrow case of Haida Nation, the SCC advised that s. 35(1) protected rights to consultation – rather than injunctions – should be pursued by First Nations because the duty to consult would better safeguard their interests. Reasoning the need for this legal shift, the Court laid out four limitations of injunctions:

first, they may not capture the full range of government obligations;

second, the duty to consult necessarily entails balancing interests and thus could go further towards reconciliation;

third, the Court cites Hunter’s argument that the balance of convenience test favours industry and jobs, prejudicing the courts against First Nations before the merits can be determined; and

fourth, stop gap measures like injunctions should not be used for complex matters, which must be given adequate time in courts to resolve.

Since Haida Nation came down, however, it has not reduced the number of injunctions involving First Nations, nor protected them any better in proceedings. It may be the case that First Nations have had more success pursuing judicial reviews of regulatory decisions or lawsuits for failures of the Crown to engage in meaningful consultation. Although these legal avenues are beyond the scope of this paper, such a comparison would undoubtedly shed light on this important question. Here, however, we seek to uncover whether Haida Nation and the s. 35(1) protected right to consultation created more opportunity for First Nations to assert and protect their rights in injunction cases. In particular, did the courts consider breaches to the Crown’s duty to consult an “irreparable harm”?

If anything, we could conclude that failures on the part of governments to comply with the duty to consult have not been seen by the courts to constitute “irreparable harm.”

Irreparable harm is at the core of injunctive relief, since it is precisely what entitles litigants to “equity’s extraordinary and discretionary relief.”

The plaintiff must show immediate harm that cannot await resolution at trial or be addressed any other way, especially through damages. For example, a 2008 Federal Court of Appeal decision in Canada v. Musqueam First Nation showed, despite the fact that lands in their traditional territory were being alienated by the Crown to third parties, the government’s failure to consult did not give rise to “a veto” on the basis of disputed territory alone.28 In other words, the potential loss of lands was not considered an irreparable harm, the judge reasoned, unless it was coupled with “possible degradation” or a specific use claim to the territory. The prerequisite for injunctive relief was only damage in a narrow sense, not the historical, cumulative state dispossession that the Musqueam sought to prevent. This is unfortunate, since injunctions could potentially provide a strong interim measure while other rights litigation moves through the courts. However, a long line of injunction cases rejects this logic.

The duty to consult was also undermined in Behn v. Moulton Contracting Ltd in 2013, when members of the Fort Nelson First Nation were chided for blockading their lands threatened by logging. Writing for a unanimous SCC, Justice LeBel concluded that “[t]o allow the Behns to raise their defence based on treaty rights and on a breach of the duty to consult at this point would be tantamount to condoning self-help remedies and would bring the administration of justice into disrepute.” ![]() Pfft, more like would have brought a tiny dab of credibility to the administration of justice in Canada, which industry rapists are unwilling to tolerate, notably if it brings a tiny measure of fairness to First Nations defending their lands, resources and territories.

Pfft, more like would have brought a tiny dab of credibility to the administration of justice in Canada, which industry rapists are unwilling to tolerate, notably if it brings a tiny measure of fairness to First Nations defending their lands, resources and territories.![]() In one of the few injunction cases ever brought to the SCC, the decision on the duty to consult set an unfortunate precedent that the applicants – as individuals, rather than as the Band – did not have standing to assert these rights, despite s. 35(1) jurisprudence that has been successfully brought to protect individuals within communities. Moreover, the Behn family’s resort to blockades was rendered unlawful despite the uncertainty over proper title to the land in question.

In one of the few injunction cases ever brought to the SCC, the decision on the duty to consult set an unfortunate precedent that the applicants – as individuals, rather than as the Band – did not have standing to assert these rights, despite s. 35(1) jurisprudence that has been successfully brought to protect individuals within communities. Moreover, the Behn family’s resort to blockades was rendered unlawful despite the uncertainty over proper title to the land in question.

Behn has proven extraordinarily influential. In Enbridge Pipelines Inc. v. Williams, a 2017 case involving representatives of the Haudenosaunee Development Institute, for example, Justice Broad cited Behn and decided that the question of “whether the Crown has made efforts to comply with its duty to consult and accommodate is not relevant to the exercise of the court’s decision to deny an injunction sought by a private party such as Enbridge with an interest in land on discretionary grounds.” The injunction was granted to Enbridge partially on the basis of the defendant’s resort to blockades, and the matter of treaty rights was deferred to proceedings in other courts.

In Williams, the court went to great lengths to distinguish an earlier Ontario decision calling for judges to prioritize the duty to consult. In Frontenac Ventures Corporation v. Ardoch Algonquin First Nation, the Ontario Court of Appeal had made every effort to encourage consultation when it impacted Aboriginal treaty rights to hunt. As Macpherson, J.A. instructed, citing Haida directly: “The court must further be satisfied that every effort has been exhausted to obtain a negotiated or legislated solution to the dispute before it. Good faith on both sides is required in this process.” Relying on Behn (and a key 2014 Newfoundland and Labrador Appeal Court decision), Justice Broad instead framed the Haudenosaunee defendants’ invocation of the duty to consult in Williams as the imposition of a “precondition involving the exhaustion of efforts to consult,” dismissing their attempt to require the Crown to consult with respect to treaty rights as an illegitimate resort to self-help.

These cases demonstrate the failure of injunctive relief for First Nations when s. 35(1) consultation rights are brought to bear. On the one hand, the SCC tried to steer land claims out of the injunction arena in Haida Nation, wisely counselling on its inherent limitations and the dangers of bias embedded in the tripartite test. But this warning backfired when – of necessity – First Nations sought urgent relief or were faced with plaintiffs seeking to remove them from their lands. Judges can then interpret Haida Nation to reason that First Nation cases should be heard in different proceedings, as litigation for rights and title, or else attempt to adjudicate their rights and title based on scant evidence on merits. This means, paradoxically, that the denial of injunctive relief to First Nations and the success of corporations and governments seeking injunctive relief against them,

practically constitutes a de facto resolution of disputed land claims. Put simply, the s. 35(1) duty consult, alongside the long delays and evidentiary hurdles standing in the way of establishing Aboriginal rights and title more generally (as demonstrated by Sparrow and Delgamuukw), has proven to mostly work against First Nations seeking injunctive relief.

3. The Public Interest as Colonial Status Quo

Section 35(1) rights do not fit easily into the tripartite injunction test because they require lengthy and careful litigation or negotiation. Yet, the use of injunctions has by no means been discontinued on this basis. In the cases we coded, (or 60 percent) referred to Aboriginal rights, treaties, and/or title in motions brought by First Nation or as defences against injunctions. Almost a third of these cases address the legal question of consultation. Many of these legal arguments are countered in the courts by public interest-based counter-arguments and reasoning.

The explicit consideration of public interest arguments in fact emerged concurrently to the

emergence of s. 35(1) case law discussed above after the SCC made two critical decisions that

emphasized the importance of public interest when balancing “convenience” in interlocutory

injunctions. While Metropolitan Stores40 (decided in 1987) and RJR-MacDonald (1994), did not involve Indigenous people, these Charter cases became central to the shift away from injunctive relief for First Nations. Their importance was due to the presumption baked into the “public interest” that an equitable balance can exist between protecting the interests of distinct groups in society and “concerns of society generally.”

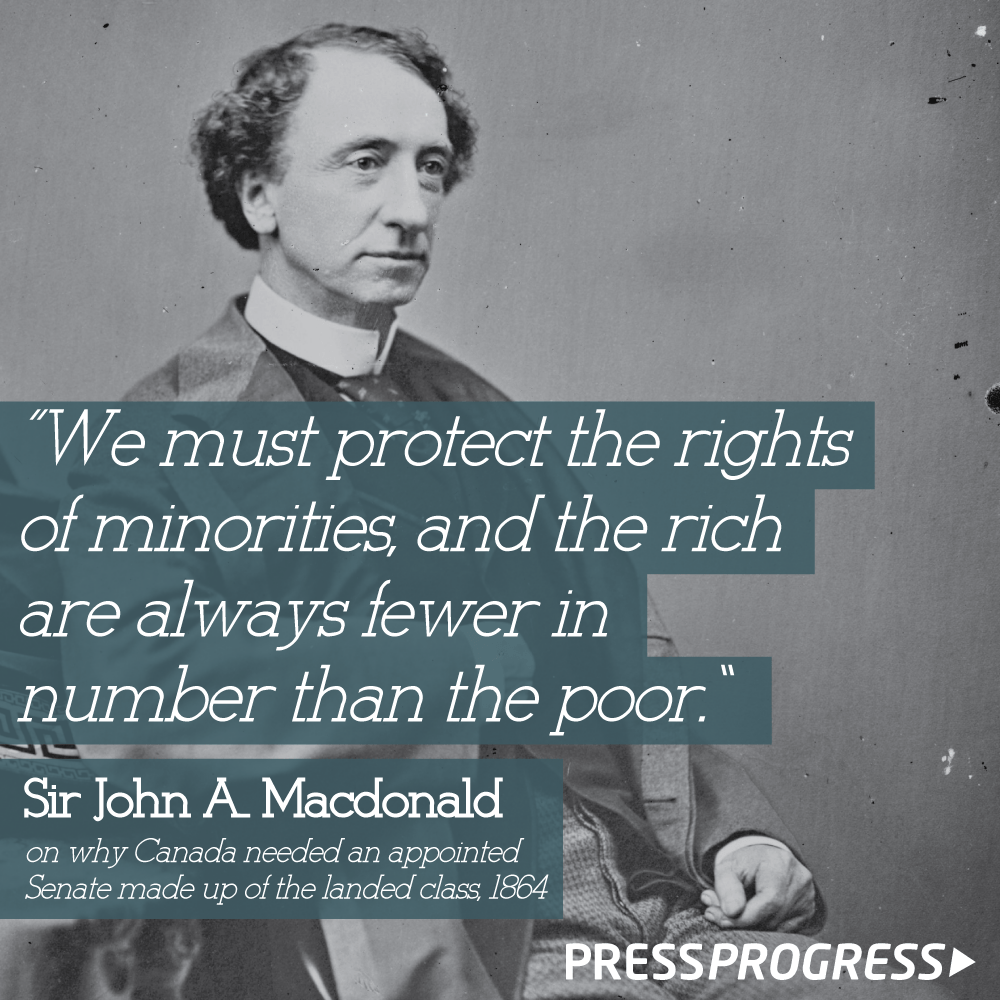

For First Nations, already struggling to assert their inherent jurisdiction against the non-justiciable nature of Crown sovereignty, the paramountcy of the public interest further prejudices courts hearing injunction applications against them. In Metropolitan Stores, cited in RJR-MacDonald, the SCC made foundational comments defining the public interest, stating that, “in all constitutional cases the public interest is a ‘special factor’ which must be considered in assessing where the balance of convenience lies, and which must be ‘given the weight it should carry.’” As the court decided:

It is, we think, appropriate that it be open to both parties in an interlocutory Charter proceeding to rely upon considerations of the public interest… either the applicant or the respondent may tip the scales of convenience in its favour by demonstrating to the court a compelling public interest in the granting or refusal of the relief sought. “Public interest” includes both the concerns of society generally and the particular interests of identifiable groups.

The public interest is further closely tied to the expectation that injunctions maintain or preserve the status quo.

The status quo is considered critical to guiding judge’s decisions on what constitutes the public interest. For Indigenous claims litigation, however, the “status quo” or the “existing legal regime or the state of affairs on the ground,” may include active mining or logging, preserving at minimum a circumstance of disputed land, and at most, maintaining a destructive or violent occupation. As detailed in this section, the uneven pattern in injunction cases also persists through the court’s interpretation of this “status quo” imperative. This interpretation that favours statutory regimes and private capital contradicts SCC decisions on the interplay of the duty to consult and the role of regulatory agencies and tribunals, which call for recognizing that the “duty to consult, being a

constitutional imperative, gives rise to a special public interest that supersedes other concerns

typically considered by tribunals tasked with assessing the public interest.”47 As such, the post-Sparrow shift away from success for First Nations obtaining injunctions is not only due to the s.35(1) jurisprudence and a diversion towards constitutional litigation. It is also due to a public interest defined by market rationale and the demand for Indigenous lands.

Reconciling the public interest of Canada’s resource economy with Indigenous rights lies at the heart of these cases.

But less examined is the way the court manages, and often shields, private interests from exposure to counter-legal claims.

For example, Hunter demonstrates that early injunctions involving First Nations were open to considering the interests of First Nations in the land, reflecting a time of relative calm within the cycles of capitalist crisis. The Ahousat and Clayoquot arguments for title to Meares Island, for example, led the judge to reject the public interest argument made by the forestry company to protect private investment. Though he admitted that the case was a “frontline” precedent for Nations across the province disrupting extraction on their land by asserting title, the fear expressed by the province and companies was not deemed a sufficient public interest argument, for this uncertainty would be up to each court in every circumstance to consider. But critically, the judge also did not find the importance of logging for the company to be a matter of “irreparable harm,” since “the timber will still be there” if MacMillan Bloedel were found to hold the right at trial. Whereas “[t]he position of the Indians is quite different,” since logging may extinguish their food sources and ways of life.

By 1989, Esson J.A. challenged this position in Westar Timber Ltd. v. Ryan et al. This case involved the Gitksan Nation’s conflict with a forestry company that sought to log and expand operations into a region over which the Nation was asserting title as part of the Delgamuukw case. The judge quoted Macfarlane, J.A.’s dissenting reasons from MacMillan Bloedel at length, emphasizing the heading “Provincial concern about sovereignty over resources,” where Justice Macfarlane wrote that Meares Island was a unique case because it was a small, isolated area. However, “[i]f an injunction were being sought with respect to the whole area the economic consequences of granting an injunction would probably weigh heavily against making the order.” Esson J.A. picked up this line of the thinking, and citing the importance of “public interest” in Metropolitan Stores, found that, “the court should not grant an injunction if the economic consequences of doing so would have a serious impact upon the economic health of the province, the region or the logging company.” Thus, the public interest argument here smothers the possibility of challenging provincial regulation that may constitute irreparable harm to Indigenous rights. As Esson, J.A. argues:

…injunctions restraining the exercise of rights granted under the Forest Act could sterilize the working of that statutory scheme just as effectively as injunctions restraining the granting of licenses and other rights, that being so, the public interest must be considered in applications of this kind.

The statutory scheme itself is framed here as a matter of public interest. But who does it protect? When it is enacted to defend the interests of non-Indigenous industry and workers against First Nation assertions of rights, the public interest here reveals the contrived division between public power and the economy. In other words, the “public” sphere of interest is the hidden background condition for the private accumulation of capital. Statutory power here “enforces its constitutive norms” through legal frameworks. When the impact of First Nation challenges to provincial regulation leads to financial loss and harm to non-Indigenous workers, the impact of “public interest” arguments doubles: it can be used to defend state regulatory powers, but also the state’s role in protecting the certainty of investment and employment in regional non-Indigenous economies.

Another example of how the public interest argument works by presuming this division is when it was invoked to dismiss a Gitskan logging injunction in 1990. The judge considered disruption to non-Indigenous logging by First Nations asserting rights, stating that, “The ‘ripple down’ effect of the consequences will be immeasurable. It is simply not possible to measure the damages of failed businesses, closed mills and people migrating from the area.”

Here, the court views the public interest as a means to protect private capital, since the economic livelihood of non-aboriginal citizens will be impacted.

The court does not recognize a public interest role in protecting Indigenous livelihood.

This interpretation of the conjoined meanings of status quo and public interest can be found as far back as our research extends, to 1973 – the earliest record we have of an injunction involving First Nations – and it is closely tied to resource extraction and development.

Though the language of “public interest” was not yet been codified in law, the idea was already evident. The court told the James Bay Cree at the time: “It is important to note at the start that hydroelectricity is the only primary energy resource possessed by the province of Quebec. With the petroleum crisis which exists actually in the world, this resource has become of a capital importance to ensure the economic future and the well-being of the citizens.” The economic well-being and future of the Cree, Innu and Inuit Nations are not included in this consideration of the project, set to enter a catastrophic phase of hydrological transformation to their territory with the largest dam project in the North America. This definition of the “interest” of “the Quebec population” represents not only a majoritarian stance regarding the principle, but also an explicitly colonial one, since none of these lands had ever been subject to treaty or surrendered. The Quebec public is prioritized as the beneficiaries of extraction, while the interests of Indigenous Nations must be sacrificed.

The natural resource economy is of central importance to Canada’s political economy and

therefore to colonization. Its idiosyncrasies have also determined “public interest” arguments in relation to First Nation rights. The backdrop to many of the BC cases Hunter studies, for example, demonstrate the boom-bust cycle of a resource sector deeply impacted by global forces. Thus, the precarity of the global commodity market is critical to the injunction story, too. Following high prices and production in the late 1970s, a devastating recession in BC in the 1980s was only temporarily corrected with a sharp boom in the 1980s, followed by another deep recession in the late 1990s. Rather than adapt technologically to yo-yoing demand, rapacious harvesting devastated the province’s interior, triggering environmental and Indigenous movements for protection, through a spate of occupations, blockades, and of course, injunctions. The global price fluctuations for timber put private interests on a razor’s edge of financial survival, sharpening corporate and state arguments of “irreparable harm” when production was disrupted. Meanwhile,

the province had to balance private interests with increasingly powerful movements demanding to protect these lands.

In other words, capitalism in Canada has two crises: first, its internal contradictions and boom-and-bust cycles of production, coupled with the natural limits of supply; and second, insecure land tenure for investment in resources on lands where Indigenous peoples challenge the Crown’s claim to underlying title and rights. In injunction cases, the courts only tend to deal with the former crisis because it fits a temporal and racial understanding of economic duress. The failures of the courts to recognize the razor’s edge of Indigenous survival after a century or more of apocalyptic changes wrought by colonization (e.g. fisheries re-routed and dammed, areas stripped bare of trees and life, animals harvested to near extinction), indicates that these harms are not legible as “economic” factors in these decisions.

![]() The stupidest aspect of our courts’ failures is that judges are extremely ignorant and short sighted by their rich white man schooling and experiences in rich white man firms and rich white man academia, corrupted by the lure of their pensions and egos, they fail to see that wiping out Indigenous peoples via man’s greed for obscene profits, wipes out the rest of humans too, and other species, and is fast destroying (no oxygen, we die; too hot, our bodies and organs boil and die) the earth’s ability to sustain life.

The stupidest aspect of our courts’ failures is that judges are extremely ignorant and short sighted by their rich white man schooling and experiences in rich white man firms and rich white man academia, corrupted by the lure of their pensions and egos, they fail to see that wiping out Indigenous peoples via man’s greed for obscene profits, wipes out the rest of humans too, and other species, and is fast destroying (no oxygen, we die; too hot, our bodies and organs boil and die) the earth’s ability to sustain life.

Super stupid. Law schools are excellent at teaching how to break the rules/law and get away with it (vital for lawyers and judges to help the rich and their corporations, and themselves, break the law and get away with it); how to memorize so as to be able to cope with the mountains of “procedure” and masses of paper work that keep the legal system inaccessible for the majority of citizens); how to be racist and cruel and get away with it; how to rape and kill and get away with it – notably raping and killing kids; how to charm and con others and get away with it; how to lie/hide the truth and cover up crimes by the rich with dreadfully boring legal mumbo jumbo; etc, but terrible at teaching the devastation to all life caused by cumulative harms (notably frac harms) from rabid resource extraction and consumption. I believe this is intentional. The status quo gives not one damn about the future, except to rape out as much profit now to feed rapacious greed with as little as possible spent to clean up during and after the raping is done, or better yet, legally walk from all accountability and clean up via court ordered bankruptcies as has been intentionally set up by the rich white man across Canada.![]()

We cannot be too fancy about the reasoning here: this is settler-colonialism, in the form of willful denial, in action.

We can see this dynamic play out through a 1996 injunction case in Manitoba, where despite

concerns regarding logging traplines, Mathias Colomb First Nation lost their bid for an injunction because, according to the court, “[i]f Repap is hindered in its activities, the consequences will be the forced closure of its plant in the Pas, Manitoba, with the consequent loss of jobs for employees and loss of revenues for Repap.” These financial losses were deemed “unrecoverable” as opposed to the First Nation’s land claims, which Repap successfully argued were merely “speculative.” These lands being logged were precisely where Mathias Colomb was negotiating an extension of their reserve boundaries to compensate for “lost lands” during the negotiation of Treaty 6. While land restitution to the First Nation would provide valuable opportunities to the community, formerly and wrongfully denied by Canadian state policy, these financial losses were not deemed unrecoverable by the court.

Time and time again, this colonial dynamic plays out in injunction proceedings in the public

interest reasoning behind determining “irreparable harm.” In a logging dispute that dragged on for many years, the Okanagan First Nation consistently lost injunction cases, despite their assertions of Aboriginal title to the land. For instance, when a motion was served against the Okanagan to stop logging without provincial authorization, the province sought a work order to preserve the status quo, stating: “when a public authority is prevented from exercising its statutory powers, the public interest suffers irreparable harm.”![]() Just galling. Frac’ing evil, as evil as AER, Alberta Environment, and federal and provincial politicians helping cover-up and letting Encana/Ovintiv get away with intentionally illegally frac’ing a community’s drinking water aquifers.

Just galling. Frac’ing evil, as evil as AER, Alberta Environment, and federal and provincial politicians helping cover-up and letting Encana/Ovintiv get away with intentionally illegally frac’ing a community’s drinking water aquifers.![]() A few years earlier, the First Nation had been unable to convince the judge that the Pine Marten and their traplines would suffer from clear-cut logging on their territory. The court found the harm to be worse to Riverside and Weyerhauser contractors, and to logging company employees who would suffer substantial losses, “which would be difficult, although not impossible to calculate.” Another logging case in BC involved the Nlha7kapmx Nation, or Siska Indian Band. Here the courts decided that since the mill is a “sunset operation” – a business that might close without access to a specific stand of trees – the injunction should be granted in their favour. In contrast, the spiritual, cultural, and economic sustenance of the community of 250 people who depend on the land was not deemed to be in immediate risk.

A few years earlier, the First Nation had been unable to convince the judge that the Pine Marten and their traplines would suffer from clear-cut logging on their territory. The court found the harm to be worse to Riverside and Weyerhauser contractors, and to logging company employees who would suffer substantial losses, “which would be difficult, although not impossible to calculate.” Another logging case in BC involved the Nlha7kapmx Nation, or Siska Indian Band. Here the courts decided that since the mill is a “sunset operation” – a business that might close without access to a specific stand of trees – the injunction should be granted in their favour. In contrast, the spiritual, cultural, and economic sustenance of the community of 250 people who depend on the land was not deemed to be in immediate risk.

Likewise, the Klabona Keepers of the Tahltan Nation attempted to stop a mine on their territory to protect the salmon runs that their nation and downstream nations have depended on for centuries for sustenance and kinship. Yet, this assertion of harm did not count as dearly as “the emotional and psychological effects of long-term unemployment,” which are harms “that cannot be compensated through damages.” Salmon are a keystone species that maintain the functional integrity of riparian systems and many species at risk that depend on their aquatic and terrestrial ecology through the province; it is difficult to image a greater impact to the region or to the people who have lived in reciprocal relation with the species for hundreds of generations. Justice Punnett of the BC Supreme Court nonetheless stated that, “In this case there is a public interest in upholding the rule of law and enjoining illegal behaviour, protecting gainful employment of members of the public, allowing the project to proceed to benefit the public, and protection of the right of the public to access on Crown roads. Accordingly, it would run contrary to the public interest to allow the defendants to persist in their blockade of the plaintiff.”

Ten years earlier, the Lax Kw’Alaams Indian Band of the Tsimshian Nation heard the same message when they sought an order prohibiting the harvesting of culturally modified trees that have been integral to the culture for hundreds of years. They were told the economic health of the region was paramount: “An injunction here would create uncertainty, not only for West Fraser but also for the logging contractor who has been engaged to perform this work, the employees hired for the work, and their families.”

Occasionally, courts will recognize that the impact of resource-based economies on First Nations’ rights require a more nuanced treatment of the public interest. In a 2011 case involving dueling applications for injunctions by Taseko Mines Ltd. and members of the Tsilhqot’in Nation, the BC Supreme Court held that it is very much in the public interest to ensure that “reconciliation of the competing interests is achieved through the only process available, being appropriate consultation and accommodation.” This process “is a cost and condition of doing business mandated by the historical and constitutional imperatives that are at once the glory and the burden of our nation” –one that would be at risk should the First Nation’s injunction application be denied and thus “weighs heavily in the balance of convenience.” Yet even in this decision, where the public interest in reconciliation played a key role in denying the mining company an injunction, a brief but unlawful interference in Taseko’s operation via a blockade by members of the Tsilhqot’in nation that appeared to the judge to “be more moral than physical” led the court to award Taseko partial costs.

First Nation blockades similarly shaped the 2019 Coastal GasLink Pipeline Ltd. v Huson decision that led to the RCMP raid on Wet’suwet’en territory in early 2020 and catalyzed the ShutDownCanada solidarity movement. Justice Church found that “interference by the defendants with valid and subsisting rights to construct a project that has been found to be in the public interest” was a form of irreparable harm that would be suffered by the plaintiff pipeline company. This finding also determined the court’s resolution of the public interest claims made by both parties. The Indigenous defendants had argued that an interlocutory injunction would harm the governance of Dark House and the Wet’suwet’en legal order generally. Coastal GasLink [CGL] submitted that the public interest should be understood more broadly because the pipeline project would bring substantial benefits to Indigenous people, local communities, to the province, and to the Canadian economy. They argued that $20 billion could be lost if the pipeline could not be built. Justice Church favourably cited these factors in her decision.

Another element of the public interest further tipped the balance in Huson in favour of the corporate injunction claimants: the idea that the practice of Indigenous law is a “self-help” remedy. In a variation on the project-centered irreparable harm analysis, Justice Church held that there is “a public interest in upholding the rule of law and restraining illegal behaviour and protecting the right of the public, including to the plaintiff, to access Crown lands.” This conclusion rests on a long line of cases, particularly the SCC’s 2013 decision in Behn, rejecting so-called self-help remedies such as blockades, occupations, and other land-based resistance strategies.

As discussed above in section 2, Behn was not an injunction case but rather addressed the ability of Indigenous defendants in a tort action to assert treaty rights and the duty of consult in their defence after being sued by a logging company for blocking access to the company’s work sites. In Huson, Coastal GasLink relied on Behn to suggest that it was the Wet’suwet’en “defendants who have moved to alter the status quo in this case by engaging in self-help remedies rather than challenging the validity of the permits and authorizations through legal means.” The “remedies” in question are a healing center on which construction began in 2010, cabins and other living quarters, as well as gates intended to control access to this small village, all of which are located on Wet’suwet’en territories on or near the pipeline route. At the interlocutory injunction hearing, CGL’s counsel Kevin O’Callaghan asserted that, “A blockade can never be seen to be the status quo.” The court agreed, reducing long-standing assertions of jurisdiction made material via occupation and land-based practices to a mere blockade and concluding that, “[u]se of self-help remedies is contrary to the rule of law and is an abuse of process.”

But which rule of law? As the defendants’ legal counsel, Michael Ross, argued on their behalf, “It is their primary defense, the defendants say, that Coastal GasLink was attempting to enter Dark House territory in violation of Wet’suwet’en law and authority and within their efforts to prevent – that is the defendants’ efforts to prevent – this violation of Wet’suwet’en law and authority, they were at all times acting in accord with Wet’suwet’en law with proper authority.” While the segments of the RJR-Macdonald test often overlap, the invocation of “self-help” allows the judicial treatment of the public interest to reinforce – or even replicate – the “maintenance of the status quo” factor also considered under the heading of the balance of convenience. “Self-help” then, is a practice that necessarily violates the status quo. Behn, in other words, allows factors like Indigenous legal orders to serve a similar function to the roles played by time and uncertainty in the aftermath of Sparrow, insulating injunctions from the reach of s. 35(1).

The cases canvassed above shed light on this doctrinal ordering of interests, in which the broad

concerns and interests of Canadian society generally (or at least the alleged concerns) will almost invariably trump the more particular public interest of First Nations. This is especially evident in cases where the “public interest” has been opposed by First Nations and has led to the assertion of Aboriginal or Treaty rights in opposition to the maintenance of the status quo. In this case of Coastal GasLink, and so many others we examined, the public interest refers to the completion or continued operation of an approved or licensed project – never to the inception or maintenance of

the Indigenous legal order or governance system.

4. Origin of an Injunction: Equity, Property, and Settler-Colonial Legality

That the “public interest” functions as a fixed nexus of exclusion within injunction law points to a more foundational problem: along with other elements of the balance of convenience test, public interest operates the way it does due at least in part to the inherently discretionary character of equitable remedies. Much as s. 35(1) rights were pushed outside of the scope of the tripartite test and the guiding principle of “public interest” preserved a colonial dynamic rooted in a resource economy, the discretionary basis of equitable remedies also carries an opportunity for bias and discrimination against First Nations that is buried in the “silent compulsion” of land struggle in Canada.

It may seem contradictory to attribute the cause of a persistent pattern of judicial reasoning to the notion of discretion but locating the equitable roots of injunctions within a broader settler-colonial framework suggests that this discretion is distinctly and historically bounded.

The power to grant an injunction derives from an old and subsumed system of English law called the Court of Equity. Although injunctions eventually came under the jurisdiction of the combined courts of law and equity, the origin of injunctions can inform us about the meaning of its remedies. Since the Court of Equity could only grant specific relief where damages (awards of money) were deemed insufficient, injunctive relief required “irreparable harm” – of a kind which could not be compensated monetarily – to be granted. Irreparable harm, then, had jurisdictional importance for which court would hear the case and therefore what the remedies would be available.

The Court of Equity itself emerged from the dissatisfaction of English people with the rigidity of the common law system of law. This led to many complaints to the King, who delegated these matters to the Chancellor to resolve through a new legal venue. Since Chancellors tended to draw from ecclesiastic classes, they resolved matters in the new courts of equity by largely drawing on canon law principles of good conscience. No less discretionary than the common law, but less bound to strict rules, procedures, and established legal precedents, injunctions were included among the equitable remedies the court provided.

Eventually, this looser system of law could not withstand the pressure exerted by commercial markets and land privatization for the more procedural and substantive rules of doctrines in the common law.

As a result, the significance of the injunction as an equitable remedy must be understood in relation to the common law. Remedies have “distinctive structures, justifications, and goals,” which are not integrated in a hierarchical way into the common law. There is much debate in Canada on where and how these discretionary lines are drawn. As Jeffrey Berryman explains: “It is up to the defendant to refute the plaintiff’s remedy of choice. But for judges, who traditionally conceive of their role as the top of an adjudicative apex, it is difficult to escape from the position that the ‘discretion,’ in that equitable remedies are said to be discretionary, is for the judge alone to exercise.” Complicating this issue, though, is that these lines are not entirely clear, especially in Canada. Equitable remedies shape substantive rights and vice versa. We can see quite clearly, for example, in the case of injunctions and First Nations how equitable remedies are shaping Indigenous peoples’ substantive rights.

The ambiguity of the relationship between these remedies and the common law is then complicated by the colonial relationship between Canadian courts and Indigenous peoples.

Much of this ambiguity can be found in property law, which the courts ultimately seek to protect when they are tasked with maintaining the status quo in injunction proceedings.

Brenna Bhandar’s exploration of racial regimes of ownership and more specifically, her examination of the “development of the specific legal forms of private property relations” in settler colonial sites, points to a framework for understanding how our modern concept of “public interest” has evolved out of this process of development. As Bhandar writes, this property law system emerged from, “political ideologies, economic rationales, and colonial imaginaries that gave life to juridical forms of property and a concept of human subjectivity that are embedded in a racial order.”

She examines, for example, the titling registration regimes of the nineteenth century in the British colonies that relied on a new racial science to deny Indigenous peoples’ own tenure system through hierarchies of racial entitlement.

Drawing on the work of Nicholas Blomley, she also theorizes the process of racial property-making as “enactments” that must be repeated regularly and reproduced through legal techniques of denial. What does it mean, then, to reconsider equitable remedies as part of these “colonial modes of appropriation” that constitute the public interest?

The public interest that injunctions protect is indelibly shaped by private property interests that underpin statutory schemes and common law constructs.

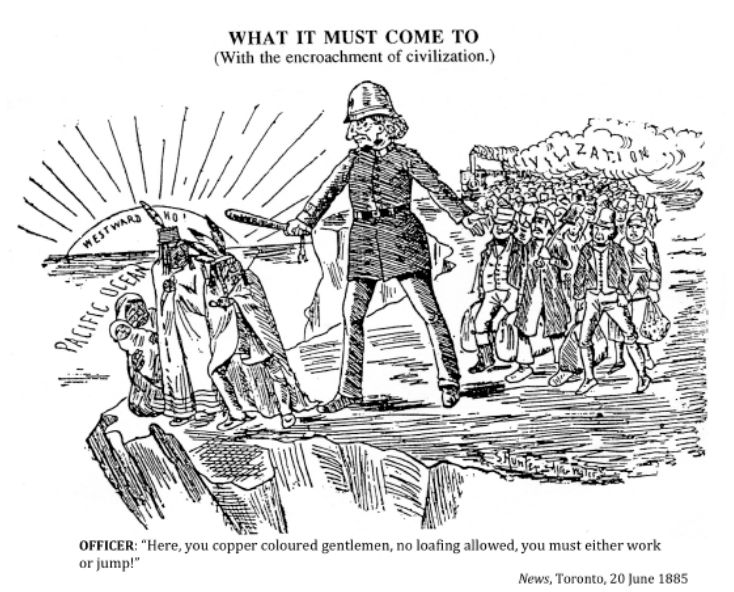

Here we need to dig a bit deeper into the relationship between colonialism, capitalism, and property law in Canada. In his examination of settler colonialism in British settlements, Robert Nichols’s work in Theft is Property! offers a critical reformulation of Marx’s important concept of “dispossession” or “expropriation” to the process of capital accumulation. Like many others, Nichols rethinks Marx’s theorization of a stadial view of violent dispossession as an essential condition for the next stage of development, a “silent compulsion of economic relations.” Rather, Nichols writes, “[t]here was no historical transition from extra-economic violence to silent compulsion, only a geographical displacement of the former to the imperial periphery.” But in Nichols’ reformulation, he avoids the common move that often follows this point, which is to prolong Marx’s theory of early “primitive accumulation” into the present in order to account for an ongoing, violent removal of Indigenous peoples from their lands. Instead, he rethinks the category of “dispossession” itself to produce an important insight into property relations in the settler colony. Ongoing dispossession is not only required to transforms nature into commodities. It is rather part of the silent compulsion of capitalism, where land is both “a conceptual and legal category that serves to relate humans to ‘nature’ and to each other in particular, proprietary manner.” It is intrinsic to the culture of settler colonialism.

Nichols traces the emergence what he calls a “hybrid private/public form” of juridical

dispossession during the settlement of Canada and other settler-colonial states in ways that are helpful in working to connect the contemporary legal tool of injunctions and the concept of public interest to more foundational property relations. Dispossession, Nichols argues, “did not proceed through macro assertions of sovereignty but through microlevel practices that worked to dismantle one infrastructure of life and replace it with another.” We can apply Nichols’ observation to Canada, where the transformation of land into property proceeded through mechanisms like the Dominion Lands Act of 1872, which also privatized the theft of territory from Indigenous peoples. This federal legislation facilitated massive land redistribution of Indigenous lands to Hudson’s Bay Company [HBC], CPR, and other “colonization companies.” Prior to this redistribution, “Rupert’s Land” was acquired through a “Deed of Surrender” in 1869 between Canada and the Hudson’s Bay Company to the lands of the Anishinaabe, Cree, Ojicree, Inuit, Innu, Dene, Gwich’in, Métis, and more, who had lived on and governed these lands for thousands of years. These “Company lands” sold to Canada, were then privatized again through the distribution of acreage to private companies and to European settlers.

It is this hybrid public/private form of property that we see protected in injunction cases.

The discretion of the equitable remedy, coupled with the racial subjectivity embedded in the colonial property right – designed to usurp Indigenous territorial authority – naturalizes a violent process of dispossession.

The implementation of the injunction on Wet’suwet’en territory, for example, was secured through the provincial authorization of permits, licenses and right of ways to the pipeline company, Coastal GasLink, despite BC’s legal uncertainty of Crown underlying title to the land.

The Delgamuukw decision led to over a decade of failed negotiations over the territory at the modern treaty table, so the province reverted to a position of denial, rather than accommodation of Aboriginal title. With the state regulatory approvals, the company was able to obtain an injunction, which was accompanied by an enforcement order so that public police forces could use their powers to remove Indigenous peoples from their lands. Extra-legal “exclusion zones” were created that blocked the Wet’suwet’en from accessing their territory, ever expanding the discretionary powers of injunctive relief into new domains of dispossession.

Writing on the reconciliation of private property rights and Aboriginal title in the courts,

Inupiat/Inuvialuit legal scholar Gordon Christie points out, “There is no such thing as a mechanical process that pushes out beyond current case law in such a way as to not implicate the invocation (however hidden and subtle it may be) of values and norms.” He suggests that the principles of reconciliation will be determined by forces of power that “infect” the courts, like the presumption that Canadian courts may decide the extent of power invested in First Nations’ governance and law, or that courts possess an “all-encompassing and overpowering set of predeterminations.”

Pessimistically, he predicts that, “The most likely extrapolation, carrying with it as it will a larger background of presumptions and hidden values and principles, follows a trajectory furthering goals and objects of colonial law and policy.” Anishinaabe legal scholar John Borrows has also addressed the uneasy reaction of the courts to pitting third party interests directly against Aboriginal title. Yet, he is clear that the usual bias must be mitigated:

“constitutionalized Aboriginal title rights should obviously trump non-constitutionalized property interests. As I have argued, to hold otherwise would privilege non-Aboriginal interests over rights constitutionally protected within the country’s highest law. This would be discriminatory.”

Patricia Owens writes that there is really no such thing as public or private violence:

“There is only violence that is made ‘public’ and violence that is made ‘private.’”

Here she is referring to the dynamics of international war, but this can be applied to Canada. Injunctions involving First Nations are often fought on the terrain of competing and contested sovereignties and counter-dispossession struggles by Indigenous peoples to maintain territorial authority over their lands.

The veil of Crown protection for private property interests over Indigenous rights and title must be brought to account.

5. Disarming the Legal Billy Club

Two related conclusions emerge from the analysis set above. First, that at least part of the answer to the question of why the RJR-Macdonald test delivers such imbalanced results in conflicts over resource extraction and Indigenous rights in the present day lies in the past and is illuminated through a re-examination of equity through the lens of settler-colonial legality. The same historical lens reminds us that the present-day political economy of injunctions cannot be divorced from the resource-based economy that continues to rest on the dispossession of Indigenous lands and jurisdiction. Second, we show that the heavy lifting done by notions of ‘public interest’ both relies on and obscures the circumvention – if not outright exclusion – of Aboriginal treaty and constitutional rights from the common law’s calculus. Although beyond the scope of this paper, the enforcement stage of injunctions, marked by broad police discretion and the further blurring of public and private, similarly relies on notions of ‘public interest’ focused squarely on the administration of justice and the reputation and authority of the superior courts.![]() Canadian judges lie, often and have been mostly racist old white men put on the bench by racist old white (usually greedy) men lawyers in politics.

Canadian judges lie, often and have been mostly racist old white men put on the bench by racist old white (usually greedy) men lawyers in politics.![]()

Both of these themes point to the need to limit the wallop of the interlocutory injunction in the short term while aiming for a more foundational reconfiguration in the long term. Accordingly, we conclude by asking what, if any, place exists in injunction law and practice for Indigenous law and governance.

Our research makes it clear that injunctions are a symptom of upstream failure to address the exercise of Indigenous rights properly, lawfully, and politically in Canada.

The focus on “self-help” remedies in Behn, discussed above in sections 2 and 3, has proliferated in the caselaw as a response to the fact that injunctions have become the default response to attempts by First Nations to enact and administer Aboriginal rights, attempts which often (41% of coded cases) involve blockades or other on-the-ground assertions of jurisdiction.

The ‘Behn effect,’ which presumptively delegitimizes such extra-legal tactics even in the absence of viable alternatives, is exacerbated by a jurisprudential framework that doles out interim and interlocutory injunctions with a tacit understanding that the matter will not proceed to trial – the injunction is the point. Underlying this pattern is one fundamental factor – the denial by the Crown and industry of Indigenous rights – a factor that cannot be overcome given the direction embedded into the injunction as an equitable remedy.

Understood this way, injunctions serve as an admission of the Crown title fiction at the heart of private property relations. A very recent decision of the BC Supreme Court, Thomas and Saik’uz First Nation v. Rio Tinto Alcan Inc., suggests that this fiction is slowly being unearthed. In a discussion of the Delgamuukw decision, Justice Kent notes the SCC’s holding that “Aboriginal title ‘crystallized’ at the same time sovereignty was asserted, hence presumably permitting the layering/burdening of radical title” but goes on to write that, “the logic of this is perplexing.

Some argue, in my view correctly, that the whole construct is simply a legal fiction to justify the de facto seizure and control of the land and resources formerly owned by the original inhabitants of what is now Canada.”

Two “harsh realities” stand in the way of undoing Crown sovereignty however: its “undeniable”

existence and “certain” continuation and the doctrine of precent. Taken together, the

reconciliation of sovereignty and the pre-existence of Indigenous societies will “not likely entail

wholesale evisceration of common-law concepts” – including those making up the law of

injunctions. Nonetheless, we argue that a reckoning lies in store for RJR MacDonald and Behn, one that builds on the promise of Haida Nation but exceeds it, shifting the juridical basis by which Canadian states and industry can intervene in struggles over lands, resources, and rights.

One such route would be subjecting the RJR Macdonald framework to the standards set out in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [UNDRIP], especially in BC, which is both the epicentre of injunctions involving First Nations and the first province to enact a statute incorporating the Declaration into domestic law. The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act [DRIPA] requires that the government of BC “take all measures necessary to ensure the laws of British Columbia are consistent with the Declaration”. Given that UNDRIP requires states to obtain the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous peoples “prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources”, DRIPA can and should be used to examine every facet of the legal framework of injunctions: the common law, rules of civil procedure, legislation such as BC’s anti-SLAPP statute, and Crown and police policies. While other provinces have not yet passed DRIPA-like statutes, similar incremental fixes are available and to some degree inevitable, given the resurgence of Indigenous legal orders and the persistence of movements calling for a fundamental reordering of Crown-First Nations relations. Injunctions currently stand as an impediment to getting landback, but the ground has shifted before, and it will again.

![]()

Refer also to:

![]() Note the T-Rex on head of J Robert Bauman, judge in the centre in photo above.

Note the T-Rex on head of J Robert Bauman, judge in the centre in photo above.![]()

Best quote of 2022: “To me, reconciliation’s all bullshit,” Simogyet (Chief) Neekt, George Muldoe, in line to take hereditary name Delgamuukw.![]() To me, reconciliation is a judicially promoted scam for govt and corporations to keep raping the public interest, Canadians and our air, water, land, food, etc. to keep stringing Indigenous hope along while raping their lands and, resources, and women and children that live near industrial man camps.

To me, reconciliation is a judicially promoted scam for govt and corporations to keep raping the public interest, Canadians and our air, water, land, food, etc. to keep stringing Indigenous hope along while raping their lands and, resources, and women and children that live near industrial man camps.![]()

2019: “Access to justice should not be just for the oil and gas industry.”

Indigenous legal scholar, Val Napoleon with one of her paintings.

2018: Val Napoleon: Indigenous scholar, law professor at University of Victoria embraces disruption

![]() In my view of of Caveman Canada, with all its glorious talk of reconciliation and rights, abuse of Indigenous has only become worse, and will keep getting worse until all resources, notably, bitumen, water, oil, gas, timber, are raped out for the global racist rich.

In my view of of Caveman Canada, with all its glorious talk of reconciliation and rights, abuse of Indigenous has only become worse, and will keep getting worse until all resources, notably, bitumen, water, oil, gas, timber, are raped out for the global racist rich.![]()