Dr. Sandra Steingraber @ssteingraber1 April 25, 2024:

At NYC City Hall with the amazing science journalist Justin Nobel and brilliant microgeologist Yuri Gorby to get the word out about radiation exposure from fracked gas. Can confirm the science stands up.

Justin brought to the presser his folder of industry documents he unearthed as an investigative reporter as he lays out the evidence in his just-released book. Radon from gas stoves could be causing 700 cases of lung cancers among New Yorkers using gas stoves.

@anniecarforo from @weact4ej shares results [of] new study on hazardous air pollution from gas stoves among residents in low-income communities where stoves in smaller apartments are often used for heat as well as cooking.

Somehow speaking eloquently without no notes! Jealous!

Former gas employee Jesse Lombardi is here to speak out for the hazards for workers. “We are selling dirty gas.”

Rolling Stone@RollingStone April 24, 2024:

A reformed fracker exposes the oil and gas industry’s toxic lies:

‘Petroleum-238: Big Oil’s Dangerous Secret and the Grassroots Fight to Stop It’ tells the story of a bank robber who became a fracker, then a whistleblower.

A Reformed Fracker Exposes the Fossil Fuel Industry’s Toxic Lies, An excerpt from ‘Petroleum-238: Big Oil’s Dangerous Secret and the Grassroots Fight to Stop It’ tells the story of a bank robber-turned-fracker who became a whistleblower by Justin Nobel, April 24, 2024, Rolling Stone Magazine

A lot more comes to the surface at an oil and gas well than just the oil and gas. The U.S. oil and gas industry produces 3 billion gallons of brine a day, and despite the innocent name, it can contain toxic levels of salt, elevated levels of heavy metals like lead and arsenic, and dangerous amounts of the radioactive element radium. My reporting journey into this topic started when an Ohio community organizer told me someone made a liquid de-icer out of oilfield brine. The product contained enough of the radioactive element radium to be defined by EPA as a radioactive waste. Yet, the company behind the product advertised it was to be used on home driveways and patios and that it was “Safe for Pets” — they had even been selling it at Lowe’s.

Unraveling how that came to be turned into a 20-month Rolling Stone magazine investigation, which won an award with the National Association of Science Writers, and eventually became my book, Petroleum–238: Big Oil’s Dangerous Secret and the Grassroots Fight to Stop It, which will be published on Wednesday. Shielded by a system of lax regulations and legal loopholes, radioactive oilfield waste has been spilled, spread, injected, dumped, and freely emitted across America. My book relies on community activists, scientists and health experts, a century of academic research, and a trove of never-before-released industry and government documents to lay out a series of game-changing reveals into the world’s most powerful industry. But my most important sources are the oil and gas industry’s own workers. None have been more deceived.

Across America, they haul trucks of toxic radioactive waste labeled as nonhazardous, thanks to an extraordinary nearly half-century-old industry exemption, and must crawl inside tanks to clean out radioactive sludge, armed with no knowledge or appropriate protection against radioactivity. Some of the biggest dangers occur at treatment facilities where highly radioactive oilfield waste is mixed with less radioactive items like lime and ground up corn cobs so the sludge can be hauled to local landfills rather than taken to secure radioactive waste disposal sites. While these facilities often remain a secret even to the very communities in which they are located, over my years of reporting, I was able to learn about them through industry and government reports and whistle-blowing workers. But none has a story like Jesse Lombardi.

Like other workers I have connected with in my reporting, Jesse grew up in a small town in Appalachia, came from a line of men who worked the region’s heavy industry, spent time in prison (Jesse was a bank robber), and got swept into the unseemly world of oilfield waste removal when the fracking boom hit in the early 2010s. But unlike other workers in my story, Jesse has chosen to speak completely on the record about practices that even shocked me. It’s a rare look at what the world’s most powerful industry really looks like from the inside. Among other reveals, Jesse conveys tactics companies use to avoid environmental regulation and accountability on injuries, and the practice of luring men recently released from prison and addicted to drugs into dangerous cleanup jobs without giving them the appropriate knowledge or protection. As Jesse states, sometimes what you have to do in life is, “Jack the e-brake, take a look back, and figure, what can I do to right some of the wrongs. Help balance the ledger.” And that is exactly what he does here.

I fear nothing as far as recourse. I am not worried about intimidation. It is not even a word that bothers me. I got security like no one’s business. I am known around here as a quite intimidating dude who doesn’t take any shit. Legally they can’t try anything, I never signed a non-disclosure. And illegally, they are not going to try anything, I will drop them where they stand. In my driveway is a sign that says, If you can see this you’re in range. You come to my house welcomed and that is the only way you come. This is my sanctuary.

My other half says, tell them. Tell the people what they need to know. It’s not a money thing. It’s not a revenge thing. Everybody does something for some reason. I got three kids. And I don’t really want to leave my kids, and their kids, to lack a better word, a world of shit.

I grew up down in Proctor, West Virginia. And Bellaire, Ohio, at my grandparent’s house out in the country. There were big factories up and down the Ohio River. My dad worked at Consolidated Aluminum and I wanted to work in a factory too, that was the dream.At 17 I left high school and went to the barges. Scrap metal, coal, lime. That was really good money. I was a young guy going down the river like Huck Finn. Ohio on the right, West Virginia on the left and I am cruising right smack dab in the middle. After the barges I did contracting around the country. I built military vehicles in Cincinnati. I built helicopters in Connecticut. I worked in silver mines in Montana, and a copper mine right outside of Phoenix, Arizona. In Nebraska, I worked at Cargill, dealing with corn and grains. The mischief probably started in Iowa.

That was a 14-month contract building front-end loaders and forklifts. It was work as many hours as possible, because that’s what I’m there to do, and get as much money as possible. So I started experimenting with coke. I use a little bit of this powder and I can work more hours. That is where the cycle started. Do more coke, work more hours, do more coke, work more hours. In Arizona it graduated into harder drugs, and I got pretty strung out. I’m a little farm kid, working 84-96 hours a week and making $10-12,000 a paycheck and there are strip clubs. Of course, I had to see every stripper in the state.

Naturally, I ended up getting fired. I took a small contract job in California. Eureka and Arcata, up in Humboldt County. And you know what I’m doing up there. Dealing, using. I end up in Ohio with a stripper back at my father’s house. A whole lot of drugs. I was there about a month. Fucking angry. Mad at the world. My dad was not proud of me. Then my mischievousness got the best of me. I thought I pulled it off once, I’m going to commit a crime, and I did. I robbed a bank. This time when they came looking for me, my dad turned me in. He knew I was strung out and in a bad way. He never knew me to be so careless. But I wasn’t going to let them catch me, so I went on the run.

I committed another crime, bought a vehicle, and I’m out. Basically, I drove until I ran out of money. Eventually I went on a vacation to federal prison. I’m not going to say I’m proud but I wouldn’t change it because it made me who I am. I did eight and a half months in the hole. That will fuck with you. You have a metal sink, metal toilet, metal shower. I slept on a cold floor, LED light on 24 hours a day. ![]() OMG! I’d die.

OMG! I’d die.![]() After a month you figure out that you need to take that thing you have, your brain, and dump it out like it’s a tote. You go through everything in your filing system and you recharge.

After a month you figure out that you need to take that thing you have, your brain, and dump it out like it’s a tote. You go through everything in your filing system and you recharge.

I came out of prison and back to Ohio. I didn’t have anything but the clothes on my back. As the frack boom came on, I had a job at a facility down by the Ohio River. I said, What do you need a conveyor belt for? And they said, Moving sand. And I said, Well then you need a covered belt, what is called a tube belt, because you are going to have sand blowing all over the place. But they didn’t want a covered belt, because that was more expensive. So I put in the regular belt, and sand blew all over the place, and I got silicosis, which is when your lungs get scarred and inflamed from breathing in silica dust. Right now, it’s just this little dot, nothing that looks like it’s going to kill you, but eventually it’s going to be a big issue. We had no clue that the extra fine sand they used in the frack could eat up your lungs if you breathed it in. So we just sat there, breathing it all in.

The first time I got called out to a frack pad was upstate New York, before fracking was banned there. The job’s coordinates are in the middle of a farm field. It was very picturesque. You got these 100-year-old apple trees and cows and all these beautiful buildings, and this old stone wall on either side as you enter the farm. It was just gorgeous, and it went on forever. We’re talking a mile, two miles, a stone wall like a work of art. It really doesn’t serve any purpose, it is just beautiful. I’m coming from a farm background and I am thinking this is the prettiest fucking farm I ever been on.

Then I’m at a security shack and suddenly it’s like I’m at an industrial facility. In the middle of this beautiful farm you have flames shooting up and all these drillers and every company known to man and I’m like what the fuck did I just pull up to? That was my introduction to fracking. I got out of the truck on this massive well pad and there are trucks and tanks and shit everywhere, and waste everywhere, just chilling in puddles, and they had their hoses, what we call noodles, lying all over the pad.

My job was to run the conveyor belt from a sand king truck into the hoppers so the sand could be mixed with chemicals then shot down the hole for the frack. I did that all over the Marcellus for five years. I was the area’s lead expert on conveyor belt systems for the oil and gas industry. But it physically beat me to death and destroyed my back and I decided, it is time to do something else. In 2015 I saw a dispatch job in Bridgeport, Ohio at $16 an hour. They hired me instantaneously. I got bumped up to facility manager pretty quick and was making $165,000 a year. Then I worked for another fracking company, and that is where I learned the fucked-up world of oilfield waste.

There are three main pathways companies take in getting into the oilfield waste business. One is just a matter of taking your business cards, scratching something out and putting something else in. That is how septic companies got into hauling brine. If he’s sucking the shit out of a porta-john or he’s sucking the shit out of an oilfield brine tank he don’t care, nobody cares. He doesn’t know about any contamination or radioactivity. They just suck stuff. And they see an opportunity in an industry with some shit that needs sucking.

Then there are the gypsy companies. They follow the oil wherever it goes. Guys from Texas move into an area and call their buddies and are like, Hey dude if you get 15 trucks over here we will make some money. I don’t know what they do to organize the money, but outside money comes in and these companies are up and running, hauling waste, or processing waste, or doing something shady to try and dispose of it and make it go away.

Then there are the mom and pops. Companies that dealt with other industrial waste services and saw the need in oilfield waste and transitioned into that. When oil and gas hit big in this area these companies were like, you know what let’s take it on. And they get a couple guys and look at one, You know how to turn a wrench, right? Yeah. Then to the other, You know how to turn a wrench, right? Yeah. Let’s go, we got a pad cleanup job.

It is 100 percent about making money. You put your morals in your back pocket. Drill baby drill. There is no regulation. There is no way to regulate this shit. No way to make it work safe. It is a ticking time bomb. I thought I was doing a great job, thought I was helping save the world. Thought I was helping American industry. Man — we polluted the living fuck out of this place.

What is happening here is the government has made an exemption to call oilfield waste nonhazardous even though it is filled with radioactive waste and all sorts of other hazardous shit, and then these workers are getting this nonhazardous shit slopped all over their chests, their hands, their feet, their toes, their faces, and they are breathing this in, and ingesting it, and drinking their sodas and eating their sandwiches and smoking their cigarettes and chewing their dip all while covered in hazardous waste that the government and the oil and gas industry has put a pretty little label on to call nonhazardous — do you see what I mean?

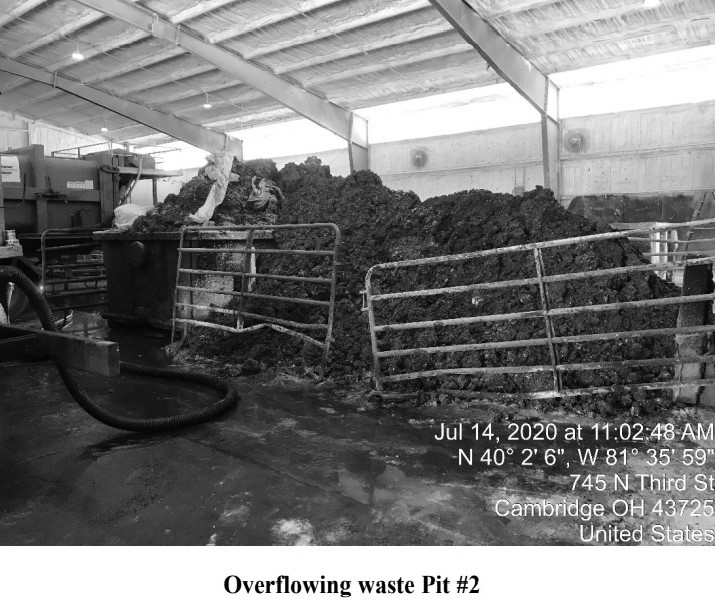

In every single oilfield you will find these oilfield waste treatment centers churning radioactive waste around like pancake mix, trying to down-blend it and lower the radioactivity. They call these places different things in each oilfield state. In Ohio they are Chief’s Order facilities, in Pennsylvania they are centralized waste treatment facilities, in North Dakota they are solids disposal facilities.

In no oilfield I have ever been to or heard of do these guys know what the fuck they are doing, do they have any training, and is any sort of concern given for their health and safety and the environment, ever.

For a Chief’s Order site, you want a good sharp hill. Then you can back stuff over the top, dump it down the hill and push dirt over. At the bottom of the hill will be a creek, the same creek that kids fish from and downstream people may be drinking from. If you are not on a hill you are at least on the creek. There might be a spot on the creek where trucks can back up to and clean-out their tanks after dumping off waste. On the site itself everything gets pressure washed, and where does that go? Everything flows down the hill, everything goes into the creek.

If you are by a river, then you are able to back down to a boat launch and suck water out of the river for your water usage. You are right there by the river, you got all these fluids, you are trying to save money. Hey Jim, you been here for 20 years, dump that in there, I’ll kick you 500 bucks. Oh yeah no problem. Splurt. Shits in the river. It’s not like typing in special numbers then you hit the launch codes at the same time. It’s not like I have to contact the president to get this okayed. It’s a matter of, I’m a fucking moron and I got some beer to drink and now I got 500 bucks in my pocket and I can buy more beer. Thanks for that safety bonus boss.

We are dealing with high pressure lines in this industry. Most of us don’t even know anything about them. We don’t know about most of the stuff on site. What is this bud? It’s a ring gasket. Where’s it go? Right there. Okay cool. No specifications, no torque specs, no nothing. But later on somebody is going to be pushing 15,000 pounds of fluid through there and it’s probably going to leak. Nobody gives a shit. And what happened to all that stuff that spilled on the ground? Nobody cares. Do you know someone with a semi? Good, bring in some gravel. EPA guy comes in, sits in his car, Notes: 12 o’clock noon, guys are on site cleaning up.

Ask the EPA guy, what time you leave bud? I’m out of here at 4. Cool, we’ll be finished up by 4. Then to your crew, Guys start wrapping up. And they are like, It’s only four o’clock, we work till 8. And I go, Start cleaning it up. It’s like mom coming to clean your room, fuck throw everything in the closet. EPA guy sees us cleaning up, he’s in his car and gone. Then me to my guys, Okay unload everything and get back to work.

Guys will pressure wash the waste off their vehicle and all that goes in the storm drain and that storm drain ends up in that creek. Nobody gives a shit.

There is a spill every day. It doesn’t matter what site you go to in this county, this state, across the country, there is a spill every single day of at least five gallons on bare naked ground. Say I am on your farmland and I have a spill. I’m not going to come to you and say, Farmer John, I had a spill. I am going to come to you and say, Farmer John I planted some new grass.

I worked with people who didn’t know how to read and write. These aren’t the brightest crayons in the box, these are guys who need to work, need that job, need to provide for their families. And they do not absorb what they are being trained on. The training is not done properly to tell the risks. There is no quiz. There is no chance to confirm. No one thinks of radioactivity.But if an audit comes and someone says, did you receive any training about radiation, they can say yes.

You want the worker who doesn’t complain. The one who will fill up three trucks of waste per hour compared to other guys who are filling up two. Man this guy didn’t complain, he didn’t need a break, he knows the job, sucks it up, puts the waste in my truck, that’s a good worker. And that is the guy you’ll give the job of hauling illegal stuff, because he is not asking any questions. People think brine trucks just haul oilfield brine, no, a brine truck hauls whatever the fuck they want off that pad. And we haven’t even gotten into tank cleaning.

Imagine going into a tiny room with a six-foot tall ceiling and these claustrophobic dividers and it’s packed full of brine or used fracking sand or sludge and the smell is horrible, and now they need to pressure wash that out so they can make that tank clean and send it back to the vendor. And the guys who go in there might be wearing their little paper yellow suits and rubber gloves and even if they have a face shield, it is probably not a full face shield, and they shovel waste out of tanks and pressure wash and it’s in their mouth and and the air, and it’s flowing down the hill. Has anyone checked that guy for radioactivity? No.

I love a guy who just came out of prison. If I were to be presented with someone clean cut, knows a lot, worked in the industry for 20 years, and your guy who has just gotten out of prison I’m hiring him. A guy who has just gotten out of prison is broke and has got to pay his bills and I got no problems. I want him. I love him. I take him. He’s going to be my star worker. He doesn’t know what the word EPA means. He doesn’t know what workers’ comp means, and no one’s going to miss this dude if we fucking kill him.

The oil and gas industry preys on the undereducated and people who live in poverty. You are being dangled a carrot and you’re like holy shit, that’s a carrot. And you come up all the way here, and it’s a muddy carrot. It takes someone willing to abandon morality and decency to come work in this industry as a manager. It is shameful to admit but that’s what it takes

I’m a high school dropout. I’m an ex-federal felon. I never was the best kid. There ain’t two ways about it. But I look like a saint compared to these oil and gas companies. The workers, the type of guys I hired, will eventually and inevitably get sick. You are never going to find them later, and you are never going to be able to hold anyone accountable. I came, I conquered, I got what I wanted, I’m out. Imagine a gazillion Jesse Lombardi’s out there with my thought process and not really morals or ethics and strung out on drugs. That’s your oil patch.

Twenty years down the line there is going to be a catastrophic fallout from this. I mean the amount of people that are going to be dying is insane. And I was a part. I got paid for destroying Mother Earth. But let me tell you something. My family worked our fingers to the bone for industry. My dad had cancer three different times. They cut out his pancreas, they cut out this, they cut out that, he got mesothelioma, he died. Virtually every single person in my family has died of cancer. My thoughts are this, I believe that I can make a change. My kids are not going to die of cancer. And if I have to be that martyr I will. Because things need to change. My grandfather wasn’t able to do it. My father wasn’t able to do it. Now it’s my turn.

Support in the research and reporting of Petroleum-238: Big Oil‘s Dangerous Secret and the Grassroots Fight to Stop It was provided by Economic Hardship Reporting Project, the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York, and other individuals, foundations and organizations.

Big Oil’s Dangerous Radioactive Secret, DeSmog writer Justin Nobel’s new book explores how workers bear the brunt of the oil and gas industry’s hidden contaminated waste by Justin Nobel, Apr 24, 2024, desmog.blog

In Paris, France, there are fine cafés and famous landmarks. But what nobody really knows is at the other end of a building known as Le V, on the northeast side of the city, is a portal that leads to a secret pile of fracking waste from the woods of West Virginia. A lot more comes to the surface at an oil and gas well than just the oil and gas, including billions of pounds of waste every day across the U.S., much of it toxic and radioactive. My journey into this topic started when an Ohio community organizer told me someone made a liquid deicer out of radioactive oilfield waste for home driveways and patios, which was supposedly “Safe for Pets” and had been selling at Lowe’s. As you will see, this indeed was the case. Unraveling how that came to be turned into a 20-month Rolling Stone magazine investigation, which won an award with the National Association of Science Writers, and an entire set of shocking DeSmog investigations. And, eventually, it all became this book, Petroleum 238: Big Oil’s Dangerous Secret and the Grassroots Fight to Stop It — available here on Amazon, here on Bookshop, or it can be ordered at any local bookstore.

It almost doesn’t seem real, and you might deny it. But really all that has happened here is a powerful industry has spread harms across the land, its people, and more so than anyone, their very own workers, and did what they could to make sure no one ever put all the pieces together. And no one ever has — until now. Many people tell me there is nothing to see here, the levels aren’t that bad. But unfortunately this is the same thing the oil and gas industry’s shadow network of radioactive waste workers have often been told. So they work on, shoveling and scooping waste, mixing it with lime and coal ash and ground up corncobs in an attempt to try and lower the radioactivity levels, without appropriate protection, sometimes in just T-shirts, eating lunch and smoking cigarettes and occasionally having barbecue cookouts in this absurdly contaminated workspace. Sludge splattered all over their bodies, liquid waste splashing across their faces and into their eyes and mouths, inhaling radioactive dust, waste eating away their boots, soaking their socks, encrusting their clothes, which will often be brought home and washed in the family washing machine, or a local hotel, further spreading contamination. Oilfield waste has been spilled, spread, injected, dumped, and freely emitted across this nation. And contamination has been discharged—sometimes illegally, often legally—into the same rivers America’s towns and cities draw their drinking water from.

More Radioactivity Than at Chernobyl

Just the other month I visited an abandoned fracking waste treatment plant on a large U.S. river where unknowing local kids had been partying. It was littered with beer cans and condoms and parts of it were more deeply contaminated with radioactivity than most of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. I was there with a former Department of Energy scientist and his Geiger counter issued a terrifying alarm — at around 2 milliroentgens per hour. He had samples tested at a radiological analysis lab and discovered the radioactive element radium to be 5,000 times general background levels.

It’s all right there in the industry’s own research and reports. And this is the beauty of science, an incredible record of our world and its ways laid out across time, and like a sacred language, it moves through time, collecting new bits and building. One can go back to 1904, when a 25-year-old Canadian graduate student named Eli described “experiments with a highly radioactive gas obtained from crude petroleum.” Or 1982, when a report of the American Petroleum Institute’s Committee for Environmental Biology and Community Health stated: “Almost all materials of interest and use to the petroleum industry contain measurable quantities of radionuclides that reside finally in process equipment, product streams, or waste.” Radium, they warned, was “a potent source of radiation exposure, both internal and external,” while the radioactive gas radon and its polonium daughters “deliver significant population and occupational exposures.” Radon is America’s second leading cause of lung cancer deaths and naturally contaminates natural gas. Which means it is being emitted out of home stoves in parts of the country at levels high enough to generate public health risks, and over time, cancer and deaths. The 1982 American Petroleum Institute report concluded: “regulation of radionuclides could impose a severe burden on API member companies.”

And they have triumphed, as the radioactivity brought to the surface in oil and gas development was never federally regulated and remains unregulated. The industry was granted a federal exemption in 1980 that legally defined their waste as nonhazardous, despite containing toxic chemicals, carcinogens, heavy metals and all the radioactivity. As the nuclear forensics scientist Marco Kaltofen has told me: “With fossil fuels, essentially what you are doing is taking an underground radioactive reservoir and bringing it up to the surface where it can interact with people and the environment.” And he said this, too: “Radiation is complex and difficult to understand but it leaves hundreds of clues.”

Known to precious few people, the mineral scale and sludge that accumulates in our 321,000-plus miles of natural gas gathering and transmission pipelines can be filled with stunning levels of the same isotope of polonium that assassins used in 2006 to murder former Russian security officer Alexander Litvinenko, by placing an amount smaller than a grain of sand in his tea at a London hotel bar. Natural gas pipeline sludge, reads a 1993 article on oilfield radioactivity, published in the Society of Petroleum Engineers’ Journal of Petroleum Technology, can become so radioactive it requires “the same handling as low-level radioactive wastes.” And yet, by U.S. law, it is still considered nonhazardous. Unlike the cosmic radiation an airline passenger is exposed to, or the X-rays of a CT scan, moving around radioactive oilfield sludge or scale invariably creates dust and particles, which an unprotected worker may easily inhale or ingest, thereby bringing radioactive elements inside their body where they can decay and fire off radiation in the intimate and vulnerable space of the lungs, guts, bones, or blood.

Then the real revelation, the oil and gas workers that politicians regularly celebrate are getting their bodies and clothing covered in waste that can be toxic and radioactive but legally defined as nonhazardous. I ask these politicians now, as workers regularly ask me, is it still nonhazardous as they are breathing it in? Or tracking it through the door of their home and into their family? This same 1980 exemption allows radioactive oilfield waste to be transported from foreign countries seamlessly across America’s borders and deposited in the desert of West Texas. I have been there.

An ‘Astonishing Scientific Story’

This is a story about worker justice. This is a story about environmental justice. This is an astonishing scientific story. We live on a radioactive planet, and oil and gas happens to bring up some of Earth’s most interesting, and notorious, radioactive elements. They can be concentrated in the formation below, and further concentrated by the industry’s processes at the surface. From day one, which in the United States was 1859, the U.S. oil and gas industry has had no good idea what to do with this waste. And so began an extraordinary campaign to get rid of it all. Modern fracking has only worsened the problem, by tapping into even more radioactive formations, bringing drilling closer to communities, and vastly increasing the amount of waste.

In a 1979 Congressional hearing, Texas oilfield regulators, using figures calculated by the American Petroleum Institute, provided a clue as to just what more rigorous regulations, ones that actually labeled the oilfield’s most dangerous waste as hazardous, might mean for the industry: a “one time cost of over $34 billion to bring existing operations into compliance” and “as high as $10.8 billion per year.” That number would be drastically higher today, but no one has done the math, in part because the full picture of costs and harms has remained unknown.

Whether it is a multinational company out of Paris, or the guy in rural Pennsylvania who stashed fracking waste beneath a courthouse, readers will be surprised at how deep this rabbit hole goes, and how close it may touch to the thing they call home, or the things they cherish. It is out of this unknowing, and deception, that this book can exist. My challenge to you is read it through to the end, and realize, this is not a book about despair — to say it, is to know it, is to change it.

Refer also to:

2012: Encana/Ovintiv getting rid of its waste at Rosebud, Alberta, Canada:

2011: Same company, same cropland as above, just upwind from my place and Hamlet of Rosebud: