In my experience of Canadian judges and lawyers, and the system’s expensive procedures intentionally created to keep ordinary citizens out, youth would do a much better job than any court in Canada could, or would ever try to.

Canadian courts were not created to serve the future, the public interest, the citizenry, our environment, or justice. The system was created to serve corporate law-violators, dirty politicians and judges, law-violating lawyers, the rich and their enablers, and to give corporations more rights than citizens – even though we pay for the costs of the system and the $billions in gifts politicians give to the polluters.![]()

***

Youth Climate Courts: a viable option by Raymond Cusson of Shoal Brook, Newfoundland & Labrador, and Tom Kerns of Yachats, Oregon, USA, May 6, 2022, The Telegram

Local governments that are not adequately addressing the climate crisis need to be called to account for failing to protect the basic rights of their citizens, and who better to do that than the young people whose rights are already being, and will continue to be, most dramatically impacted. One flexible and innovative way youth climate leaders can call their city or provincial government to account is to create their own local Youth Climate Court, with a youth judge, youth prosecuting attorneys and youth jury members and put their local city or provincial government on trial for not living up to its human rights obligations. Youth leaders will then organize a trial and summon representatives of that government to attend and explain the government’s actions and inactions in open Youth Court. Charges will be that the government is failing to adequately protect the basic human rights of its citizens, especially of the children, in face of the threats of climate change. Although not part of the current regular courts of law, this new concept addresses with a court-like process, the fundamental moral obligations of governments to protect their citizens’ human rights.

Why Human Rights? Because human rights -to life, health, an adequate standard of living, food, water, sanitation and a healthy environment as well as the rights of Indigenous peoples and other vulnerable populations- are recognized as basic moral minimums for governments. Because the primary function of any government is to secure the rights of its citizens. And, because the climate crisis is already undermining the enjoyment of our rights and threatens to undermine them even more in the coming years. Human rights serve as the clear moral standard against which government policies and practices are properly measured. In short, the future belongs to today’s young people and it is their right to use their voice to protect their future world.

Once summoned by a Youth Court, will governments be likely to send a representative to the Court or not? We believe they will because most local governments include at least a few members who, even if they are not in the majority, recognize the seriousness of the climate crisis and who worry that so little (perhaps nothing) is being done locally to address it. Those members will want to attend and make sure their government’s inaction is made public.

But if the government representatives elect not participate, the Youth Court should publicly call them out for that. If the government cares so little about the rights of its youth that it didn’t even bother to respond, show up and make its case, the public should know that. The youth judge and prosecuting attorney can point out to the media that perhaps the government had no case to make. Perhaps its representatives were ashamed how little the government had done.

And then the trial proceeds without them. A Youth Court defense attorney could possibly be assigned to represent the absent government if the Court so chooses, but that defense attorney could not be expected to make a very strong case, perhaps not any case at all, to defend a government that declined to even attend. After all, an empty defendant’s chair during the proceedings would be very telling.

One value of a Youth Climate Court trial, in addition to the opportunity it provides youth to raise their voices and exercise their powerful agency, is in the moral pressure it puts on a government, to recognize and live up to its human rights obligations to its citizens.

In addition to the website for the Youth Climate Courts, a fuller explanation of how a Youth Climate Court works, including the various roles involved such as youth judge, youth prosecution team, youth jury, etc. can be found in Youth Climate Courts: How You Can Host a Human Rights Trial for People and Planet, by Tom Kerns.

See you in court!

***

Kerns, Thomas A. Youth Climate Courts: How You Can Host a Human Rights Trial for People and Planet. London and New York: Routledge, 2022. 124p. $21.56 (paperback).

This is a marvellously clear and helpful book for anyone in their teens or early twenties wishing to become involved in fighting climate change. One of the best means for doing so are the Youth Climate Courts, an increasingly popular and effective method being pursued to encourage governments to act. This book is a concise introduction to such Courts, and Tom Kerns brings to the subject a wealth of experience and knowledge; he is currently the Director of Environment and Human Rights Advisory and Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at North Seattle College, USA. He was also involved in drafting an international declaration of human rights as they pertain to climate change and has written extensively on the topic.The book’s first chapter describes how a Youth Climate Court works and how youth activists can start one, ideally at the local level. With much preparation and some help from adult mentors and guides, youths take on particular roles in a public courtroom setting, either as judge, prosecuting attorney, or a member of the jury, calling upon representatives from their local government to stand before the Court and explain what the government has done (or not done) to facilitate meaningful action and legislation on climate change. While the Court’s sentence is not legally binding, the Court can make suggestions to its local government and develop a follow-up, science-based action plan. The intent is not to humiliate members of government but to work with them to implement meaningful change; and, because a democratically elected local government is beholden to its public, the Court most likely will receive a receptive ear from those in positions of authority.

Particularly praiseworthy in this book are the many reasons given that explain why a Youth Climate Court can be effective. Kerns cites reports that show that youth are and will continue to be more adversely affected by climate change and they will be around longer to deal with the consequences. As such, youth can speak with a great deal of moral authority and weight in their community. Far from being pointless mock theater, a Youth Climate Court can raise public awareness in a community about local environmental challenges and how the government at hand could engage more purposely in the struggle against climate change at the local level. Furthermore, as Kerns notes, “[T]he deep moral urgency of direct appeals from young people can actually make it easier for governments to undertake the kind of major policy initiatives that they know will be necessary” (p. 36). The actions of Youth Climate Courts could even muster support and awareness of larger, formal court cases being undertaken at upper levels of government.

Importantly, the book bases the operating principles of Youth Climate Courts on human rights, as opposed to statutory law. Such an approach is more appropriate for Youth Climate Courts, because human rights are universally applicable to all people and the language of human rights is more accessible than that of statutory laws, which are often specific to time and place and written more for legal specialists. Many of the courses that I teach deal with the history of human rights (the liberty of conscience and the freedom of religion; political and civil rights during the American and French Revolutions; the abolition of Atlantic slavery, and so on). Movements for human rights succeeded or at least made significant progress because of popular participation. Popular participation creates momentum and critical mass, and this is all the more potent given that governments must base their legitimacy on the extent to which they uphold and protect human rights.

Today, ideas of human rights as enshrined in international declarations and covenants have expanded beyond political and civil rights to include the right to life, the right to health, the right to water and sanitation, the right to a healthy environment, the rights of the child, and the rights of Indigenous peoples. Kerns’ book devotes two chapters to discussing these critical links between environmental justice, human rights, and fighting climate change. The chapters are filled with human rights citations, references, and arguments to use in a trial. Also useful in the book are the appendices on the Declaration on Human Rights and Climate Change, the burgeoning legal notions of the rights of nature, and possible avenues that a local government could incorporate into its Climate Action Plan. There is a wealth of material available for a Youth Climate Court to build a case!

Maybe one day our understanding of rights will expand further to include more fully the rights of nature and non-human beings; that development could extend a government’s obligation to protect habitat from the ill effects of climate change. For now, however, there is still much that can be done and Kerns’ book provides young environmental activists with a clear roadmap to guide the way.

Book Review by Edwin Bezzina

Edwin Bezzina is a Board member and newsletter editor of the Western Environment Centre of Newfoundland and Labrador (wecnl.ca) and an associate professor of Historical Studies at Memorial University of Newfoundland (Grenfell Campus), Canada

LNG exports will add to climate change by Anthony Ingraffea, Ph.D., and Robert Howarth, Ph.D., April 18, 2022, The Hill

The Biden administration is issuing orders to expand the amount of liquified natural gas (LNG) that it exports by over 50 percent as Europe seeks to reduce its reliance on Russian gas. However, by doing so we are decreasing our own energy security, while increasing climate-harming methane emissions and diverting capital expenditures away from green energy to yet more new fossil fuel infrastructure. There are better ways to aid our European allies in their time of energy need.

The U.S. tripled its worldwide LNG exports between 2019 and 2021. At our current internal consumption rate, the U.S. Energy Information Agency estimates that the U.S. currently has about a 15-year remaining supply of its own natural gas. However, in 2021 the U.S. exported the equivalent of about a 2-month supply of our gas as LNG to Europe and Asia. With the rush to increase our LNG exports, 100-fold since 2015, we are diminishing our energy security at an increasing rate.

Leakage of unburned methane into the atmosphere from the internal U.S. oil and gas supply chain is a major source of a very potent greenhouse gas, about 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide. However, the climate impact from that supply chain is worsened when it extends to Europe. Research-based on a recent study by the Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory shows that at least 230 million additional kilograms of methane leaked from the 28 billion cubic meters of natural gas exported from the U.S. to Europe as LNG last year. That is equal to about 16 percent of methane emissions from all sources in New York state. However, LNG exports to Europe will be increasing, at an increasing rate, so that leakage will only get worse.

Actual methane leakage from the oil and natural gas supply chain in the U.S. is inevitable and is now known to be far higher than estimates from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). At least one-quarter of our total methane emissions is from that supply chain. Sending increasing amounts of that gas for export as LNG adds leakage from pipelines to export terminals, the liquefying process, off-gassing during sea transport in cryogenic tankers and re-gasification and additional pipelining in Europe. Add the carbon dioxide emissions associated with all of these additional energy-hogging processes creates a nightmarish greenhouse gas footprint for LNG exports.

This rapid upscaling of U.S. LNG exports is demanding new pipelines, export facilities and cryogenic tankers. This deflection of capital expenditures away from green energy deployment has two major results: First, it’s a further delay in the green energy transition needed to increase the supply of renewable energy. Second, this increased demand for natural gas production comes at a moment when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the International Energy Agency and all others truly concerned about climate change are saying no funds should go to new fossil fuel exploration, production and infrastructure.

It is crucial to emphasize that a well-intentioned move to aid our European allies has serious consequences, intended and unintended. Like the industry’s cry for massive blue hydrogen production, which also demands an increase in natural gas production, this rapid increase in U.S. exports of LNG is tossing another lifeline to a dying industry. We cannot fail in our fight against climate change while helping to win a war exacerbated by a Russian natural gas cudgel.

So, what should we do instead? Accelerate the energy transition processes already underway in Europe. Help to decrease its demand for Russian natural gas. Most of the imported natural gas is used to generate heat for residential and commercial use, space and water heating and cooking and drying. Therefore, electrify all these uses and gain the tremendous embedded efficiency increases: Electrification actually reduces the total energy demand for these end uses. The U.S. should be exporting boatloads of high-efficiency electrical appliances and heat pumps to Europe. Simultaneously, accelerate the production of renewable energy to replace Russian natural gas. More boatloads from the U.S. of wind turbines, PV electrical components and battery storage systems. As EU Climate Policy Chief Frans Timmermans said, “The answer to this concern for our security lies in renewable energy and diversification of supply.”

The European energy crisis brought on by the Russian invasion of Ukraine has made clear that the key to energy security for all nations is the realization that nobody owns the infinite and free supplies of solar, wind and hydro energy. They cannot be weaponized. We need to do all we can to export to Europe what will win the energy war in the long run while not imperiling the rest of the world with more greenhouse gas emissions.

Anthony Ingraffea is the Dwight C. Baum professor of engineering emeritus and Weiss presidential teaching fellow at Cornell University.

Robert W. Howarth is the David R. Atkinson professor of ecology and environmental biology at Cornell University.

Refer also to:

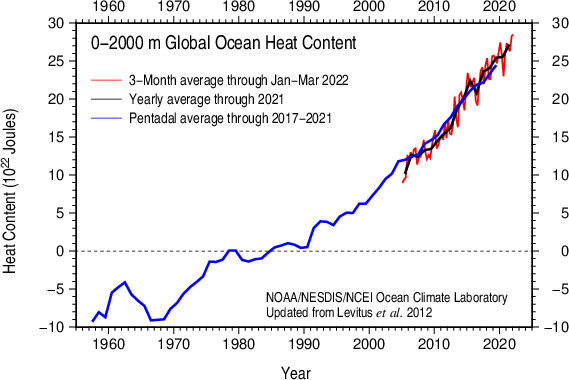

2022: Global Ocean Heat and Salt Content: Seasonal, Yearly, and Pentadal Fields National Centers for Environmental Information

Data distribution figures for temperature and salinity observations, temperature and salinity anomaly fields for depths 0-2000m, heat content and steric sea level (thermosteric, halosteric, total) are updated quarterly. Temperature anomalies and heat content fields are detailed in World Ocean Heat Content and Thermosteric Sea Level change (0-2000 m), 1955-2010, publication (pdf, 8.1 MB). The same calculations have been extended to keep the fields current and include fields of salinity anomalies, and steric sea level components. Explanation of differences in heat content between published work and online values is outlined in the comments (pdf, 4.2 MB). Information regarding erroneus values is outlined in the notes.

Updated through March 2022