2012: CO2 in Stream, Dead Ducks Prompt Wyo. DEQ Citation against Anadarko

The leak happened in an area where CO2 is injected underground to help revive an old oil field and boost oil production. The Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality has ordered Anadarko Petroleum to identify and control the carbon dioxide leak into Castle Creek in central Wyoming. The Casper Star-Tribune reports…DEQ also is telling Anadarko to monitor the stream’s acidity until three consecutive tests show normal pH. A state violation notice says company officials identified a nearby carbon dioxide injection well as the possible source of the leaking gas. Anadarko spokesman Dennis Ellis says Anadarko hasn’t yet verified where the gas originated.

James Joyce is right about history being a nightmare–but it may be that nightmare from which no one can awaken. People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.

James Baldwin

2021: Honest Government Ad, Carbon Capture and Storage FUNNY!

The Australien Government has made an ad about Carbon Capture and Storage, and it’s surprisingly honest and informative.

***

Sour Gas damages the brain, even at very low levels (after I posted these, authorities removed the documents from public access, that’s how our harm-enabling regulators regulate:

1. Exposure to levels below 10 ppm permanently damage the human brain

2. Harm from levels below 10 ppm by Worksafe Alberta

3. Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) LOW LEVEL HEALTH HARM WARNINGS:

Sour Gas Concentration (ppm)/Symptoms/Effects

0.01-1.5 ppm/Odor threshold (when rotten egg smell is first noticeable to some). …

2-5 ppm/Prolonged exposure may cause nausea, tearing of the eyes, headaches or loss of sleep. Airway problems (bronchial constriction) in some asthma patients.

***

The Gassing Of Satartia: A CO2 pipeline in Mississippi ruptured last year, sickening dozens of people. What does it forecast for the massive proposed buildout of pipelines across the U.S.? by Dan Zegart, August 26, 2021, Huffpost.com

It was just after 7 p.m. when residents of Satartia, Mississippi, started smelling rotten eggs. Then a greenish cloud rolled across Route 433 and settled into the valley surrounding the little town. Within minutes, people were inside the cloud, gasping for air, nauseated and dazed.

Some two dozen individuals were overcome within a few minutes, collapsing in their homes; at a fishing camp on the nearby Yazoo River; in their vehicles. Cars just shut off, since they need oxygen to burn fuel. Drivers scrambled out of their paralyzed vehicles, but were so disoriented that they just wandered around in the dark.

The first call to Yazoo County Emergency Management Agency came at 7:13 p.m. on February 22, 2020.

“CALLER ADVISED A FOUL SMELL AND GREEN FOG ACROSS THE HIGHWAY,” read the message that dispatchers sent to cell phones and radios of all county emergency personnel two minutes later.

First responders mobilized almost immediately, even though they still weren’t sure exactly what the emergency was. Maybe it was a leak from one of several nearby natural gas pipelines, or chlorine from the water tank.

The first thought, however, was not the carbon dioxide pipeline that runs through the hills above town, less than half a mile away. Denbury Inc, then known as Denbury Resources, operates a network of CO2 pipelines in the Gulf Coast area that inject the gas into oil fields to force out more petroleum. While ambient CO2 is odorless, colorless and heavier than air, the industrial CO2 in Denbury’s pipeline has been compressed into a liquid, which is pumped through pipelines under high pressure. A rupture in this kind of pipeline sends CO2 gushing out in a dense, powdery white cloud that sinks to the ground and is cold enough to make steel so brittle it can be smashed with a sledgehammer.

Even Durward Pettis, a contract welder for Denbury and chief of the local Tri-Community Volunteer Fire Department, didn’t figure out that the mystery fog was CO2 for a full 15 minutes. He’d directed first responders to set up three roadblocks to prevent traffic from entering the area. But it wasn’t until 7:30 p.m. that word went out that they’d need self-contained breathing apparatus, or SCBA, to enter Satartia and evacuate the town’s 42 residents, many of them elderly, and about 250 others who lived just outside town. By then, rescuers and residents were already in motion, fleeing the gas or evacuating others.

Even once Pettis figured it out, none of the sheriffs’ deputies and volunteer firefighters had any emergency training in CO2 leaks. Neither did staff at two area hospitals, which had detrimental consequences for gas victims, according to interviews with many of the 49 who were hospitalized.

“It was bad enough that I thought my mama wouldn’t make it, and she still has trouble breathing,” said Army veteran Hugh Martin, who fled Satartia in a pickup truck with his 78-year-old mother as he struggled to remain conscious. “She never had asthma or COPD, now she’s on inhalers full time.”

Even months later, the town’s residents reported mental fogginess, lung dysfunction, chronic fatigue and stomach disorders. They said they have trouble sleeping, afraid it could happen again.

This story is the result of a 19-month HuffPost/Climate Investigations Center investigation into the Satartia pipeline rupture, and the safety of CO2 pipelines. It is based on interviews with more than 60 witnesses, victims, first responders, lawyers, medical and toxicological experts, pipeline and petroleum experts, and public health officials; and a review of medical records, police and fire reports, 911 recordings, emergency dispatch logs, internal documents from the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency and the state Department of Environmental Quality, as well as federal pipeline incident reports.

Meanwhile, the federal government is taking the first steps to vastly increase the size of the nation’s carbon dioxide pipeline network ![]() as a way of taking billions of dollars from the public purse and giving more corporate welfare to the polluting oil and gas industry

as a way of taking billions of dollars from the public purse and giving more corporate welfare to the polluting oil and gas industry![]()

as a way of fighting climate change. Our investigation reveals that such pipelines pose threats that few are aware of and even fewer know how to handle.

“We got lucky,” said Yazoo County Emergency Management Agency director Jack Willingham, who oversaw the rescue effort. “If the wind blew the other way, if it’d been later when people were sleeping, we would have had deaths.”

A Deadly Gas

Carbon dioxide has long been used to euthanize laboratory rodents and other small animals, a practice animal welfare organizations now consider inhumane due to the suffering the gas inflicts on the animals.

Each year, CO2 accidents kill about 100 workers worldwide — often in basements of restaurants that use CO2-charged systems for their bar mixers — or in industrial accidents.

Carbon dioxide is an asphyxiant that displaces ambient oxygen, making it more difficult to breathe. Smaller exposures cause coughing, dizziness and a panicky feeling called “air hunger.” As CO2 concentrations get higher and exposure times longer, the gas causes a range of effects from unconsciousness to coma to death. Even at lower levels, CO2 can act as an intoxicant, impairing cognitive performance and inducing a confused, drunken-like state.

Denbury’s entire business is built around piping carbon dioxide to oilfields and a few industrial users in two operational centers in the Gulf Coast and the Rockies. It owns or has an interest in 14 oil fields in Mississippi, Texas and Louisiana, which are connected by five CO2 pipelines spanning 925 miles. Among its properties is Tinsley Field, adjacent to Satartia, which became Mississippi’s first commercially successful oil field in 1939.

In 2007, Denbury built its 31-mile Delta pipeline to connect Tinsley to the Jackson Dome, an extinct volcano under Jackson, Mississippi, whose 4.6 trillion cubic feet of naturally occurring CO2 gas supplies all of the company’s fields. Denbury extended the Delta line 77 miles to Louisiana’s Delhi field in 2009.

Denbury uses the CO2 for enhanced oil recovery, or EOR, which uses the gas to flush more oil out of wells. About 20% to 40% of the oil in a field can be recovered through conventional drilling and injecting water into the reservoir.

Injecting CO2 after that can increase the yield up to 60%.CO2 use in oil fields has resulted in accidents in several states and abroad. Tinsley itself suffered a sizeable CO2 “blowout” ― where injected CO2 explodes out of the ground along with water, mud and drilling fluids ― in 2011 that took 37 days to bring under control, sickened one worker, and killed deer, birds, fish and other animals.

Denbury had already had two other blowouts in Mississippi, one requiring the evacuation of local homes in Amite County in 2007. Another underground CO2 blowout at Delhi field in 2013 lasted for more than six weeks and contaminated the air with unsafe levels of both CO2 and methane.

Denbury and other companies that do EOR are well versed in the dangers of CO2. At Denbury’s Heidelberg Field in eastern Mississippi, signs warn of a CO2 hazard and say SCBA must be worn, and there are muster stations where workers gather if there is a release. The company also has safety pamphlets on its website ― one for the public called “Pipeline Safety Is Everybody’s Responsibility” and another for first responders titled, “AWARE: Tactics for Responding to a CO2 Pipeline Leak.” None of the emergency workers interviewed for this story had seen either.

While the risks of CO2 exposure were well established, the Satartia gassing was the first known instance of an outdoor mass exposure to piped CO2 gas anywhere in the world, according to Marcelo Korc, chief of the World Health Organization’s Climate Change and Environmental Determinants of Health Unit, whose staff researched injuries from CO2 pipeline leaks in response to an inquiry from HuffPost.

Korc’s staff also found that CO2 from the Jackson Dome is contaminated with hydrogen sulfide, a deadly gas that likely worsened residents’ symptoms and also accounts for the gas cloud’s odor and greenish color, since pure CO2 is odorless and colorless.

Denbury declined to answer specific questions for this story, sending only a statement:

On February 22, 2020, at approximately 7:00 p.m., Denbury Enterprises’ Delta pipeline experienced a sudden rupture and release of CO2 gas near Satartia, Mississippi. Before, during, and after the event, Denbury’s main interest has been the health and safety of the residents in the vicinity of the release and the surrounding environment. Denbury and its personnel were quickly in the community, working directly with nearby leadership and any individual residents affected by the event to ensure that any needs arising from the event were met. We have continued to work closely with the community and have made significant contributions to local emergency response organizations to support the important role they play in keeping the community safe. Denbury has cooperated fully with all federal, state, and local agencies who responded to the incident. The federal agency charged with regulating the pipeline continues its review and investigation of the incident, and Denbury continues to cooperate fully with their efforts.

Beyond the suffering of those who lived through it, the fact that the Biden administration is poised to commit unprecedented billions to carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology — putting CCS at the center of the country’s strategy for ![]() stealing from taxpayers to give ever more in corporate welfare to polluting, billion dollar profit raping oil and gas companies

stealing from taxpayers to give ever more in corporate welfare to polluting, billion dollar profit raping oil and gas companies![]()

reducing greenhouse gas emissions — further magnifies the importance of Satartia’s CO2 accident.

The historic hike in federal support for CCS infrastructure includes taking the first steps toward the construction of a continent-spanning network of pipelines in order to move America’s many millions of tons of CO2 to storage areas where, theoretically, the gas can be injected deep underground and sequestered indefinitely.

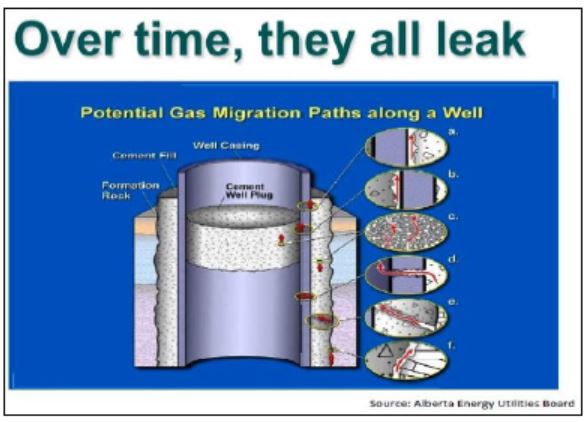

Reality Check, image by Alberta’s energy regulator in 2007, from presentations on industry’s serious leak problems:

End Reality Check.

Some experts estimate this network will need to be as large as or even larger than the 2.6 million miles of existing petroleum pipelines. Meanwhile, there are only 5,000 miles of existing CO2 lines, meaning there is little experience with a wide range of operational — and safety — issues likely to arise from such a massive new system.

Nevertheless, Biden’s climate team; his Department of Energy and three of its former secretaries; most utilities; the coal industry and the governments of several coal states; ExxonMobil, the rest of Big Oil and other major industrial corporations; several climate NGOs; the AFL-CIO; and a bipartisan group that spans both houses of Congress all support CCS and the pipeline expansion in some form. ![]() because they’re well aware that CCS is a con; fools most; risks workers, wildlife, communities; contaminates aquifers already under seige by frac’ing (which is also massively subsidized by taxpayers and rips off investors); increases fossil fuel production and pollution, while stealing billions of public dollars to give to the rich? Or, have they been conned by industry’s usual evil lies, promises and deceptions?

because they’re well aware that CCS is a con; fools most; risks workers, wildlife, communities; contaminates aquifers already under seige by frac’ing (which is also massively subsidized by taxpayers and rips off investors); increases fossil fuel production and pollution, while stealing billions of public dollars to give to the rich? Or, have they been conned by industry’s usual evil lies, promises and deceptions?![]()

“We want to build more pipes,” DOE Secretary Jennifer Granholm told a reporter in June. “There’s a lot of jobs that are associated with decarbonizing … and I think pipes are one of those opportunities.”

But the rush to build and operate an integrated CCS and pipeline system has so far taken place with little examination of the safety issue, as the people of Satartia learned.

Korc of the WHO worried that the basic science done long ago on many toxic chemicals, including petroleum products, has never been done for CO2.

“The exposure studies simply don’t exist,” he said.

Satartia was, in effect, an unwitting case study for a monumental project.

“They Can’t Come Evacuate Y’all”

DeEmmeris Burns was returning to his mother’s house in Satartia from a fishing trip with his brother Andrew Burns and cousin Victor Lewis when they heard an explosion and then a deafening roar, like a jet engine. The stench of rotten eggs filled the car.

DeEmmeris Burns immediately thought: pipeline explosion. He knew there was one nearby, but other than its approximate location, knew nothing else about it.

They were driving on Perry Creek Road, a gravel and dirt country lane that hugs its namesake waterway and passes close to but below the location of the pipe rupture. They were almost at his mother’s house.

He called his mother’s cellphone at 7:18 p.m. and told her there had been a gas explosion.

“You got to get out. We’re close, we’re coming to get you,” Burns shouted over the roar of escaping gas.

On the other end of the call, 65-year-old Thelma Brown was trying to figure out why her son sounded so strange. He was hollering, breathing heavily, not making sense. She knew the pipeline he was talking about; it runs about half a mile from her house. But she hadn’t smelled anything. She heard her son frantically repeating, “Cut the air! Cut everything off! Cut the air!” And then, silence.

She tried calling him back. No answer. She rang the other two men’s cell phones, but got nothing.

Inside the car, the three men rolled up the windows to keep out whatever it was they were driving through. Then the engine died.

“Hunh,” Burns said. “Car shut off.”

Minutes later, Thelma’s sister, Linda Garrett, who lived just down the road, smelled the gas and called too. Thelma repeated what her sons had told her before their call dropped.

Garrett hung up with Thelma and called 911, but the dispatcher didn’t seem to know about a gas leak.

“Do I need to be getting out of here?” Garrett asked. The 911 operator said she’d call her back and let her know.

“She can’t breathe. She’s on the floor right now”

Garrett noticed her own breathing was becoming labored. Then her daughter Lynett Garrett and 14-year-old granddaughter, Makaylan Burns, who had been out picking up a pizza for dinner, staggered in the door.

Makaylan seemed to be in full-blown respiratory distress, and Lynett was unable to talk. She pounded on the dining room table and panted.

“What is it? What’s wrong? What is it?” Garrett shouted.

Makaylan dropped to the floor, unconscious.

Garrett tried 911 again. This time the operator acknowledged that there was a gas leak.

“They have shut the highway down because of it. They’re not letting anyone in, they can’t come evacuate y’all,” she said.

Garrett was afraid if they left the house, all three of them would pass out. She insisted on an ambulance. The dispatcher said one would meet them outside of town.

Garrett and Lynett carried Makaylan out to the car. Garrett had a bad back and both adults were having trouble breathing, but they managed to get the teenager into the back seat, still unconscious.

Lynett drove and Garrett stayed on the phone with 911 as the operator told them the best route out of town. But after a few minutes, Garrett’s breath “just cut out.” “We ain’t going to make it,’’ she said, before she blacked out. Lynett drove to where they were supposed to meet the ambulance, but it didn’t show up, and she had to drive to the hospital.

Back at her house, Thelma Brown ran outside to round up her 8- and 3-year-old grandchildren. She brought them into her bedroom, along with her 2-month-old grandson. The oldest, who has asthma but hadn’t suffered an attack for some time, was having trouble breathing, so she gave him his albuterol inhaler. She gave some to the 3-year-old too, since she had been outside. Brown closed the windows and blocked air from coming in under the door with a wet towel.

Other relatives called, urging her to get out. But her pickup had a flat, and she was alone with three children. Her daughter was supposed to come get the kids after work, but called and told Brown that all the roads into the area were blocked off. Garrett told Brown what 911 had told her: that emergency workers were not coming into town to evacuate victims.

“I talked to the Lord. I said, ‘Lord, me and these kids going to bed,’” recalled Brown. “And I said, ‘We’re going to stay here until somebody comes and gets us out of here.’”

She waited for her son and the others to show up. She fell asleep.

At the same time, a group of friends were cooking crayfish and sipping beer at a fishing camp along the Yazoo River. It was getting dark when Hugh Martin noticed the rotten egg smell. Soon they were all wheezing and breathing hard. Martin’s friend, Casey Sanders, collapsed onto the ground, then quickly came to.

Coughing and choking, everyone somehow made it to their vehicles. Martin jumped into his white pickup truck and drove up onto the levee that separates the town from the river. The glare of his headlights illuminated a green, misty fog. The suffocating feeling was nearly intolerable. “Only thing I been through worse than this was the gas chamber when I was in the Army training for Desert Storm,” he said. “And that was cyanide gas.”

He called his elderly mother, Marguerite Vinson,who told him she was feeling dizzy.

“Got your shoes on, mama?” he asked, trying to keep the anxiety out of his voice. He told her to meet him in the carport of their home, not far from the fishing camp. After stopping once to throw up out of the truck window, he made it home.

“I saw mama standing there, holding her phone, and she was weak at the knees. And I just grabbed her and throwed her in the truck,” said Martin. “Then I just took off and headed for the highway.”

At the stop sign at Route 3 was a checkpoint, but he blew by it, heading north to the hospital in Yazoo City. His mother lay motionless on the passenger’s seat: Her eyes were open, but she stared blankly ahead when he spoke to her.

At the hospital, he found others from the crayfish cook, including Casey Sanders, and learned that her teenage son, Nathan Weston Sanders, and his girlfriend were missing, after leaving the fishing camp minutes before the explosion.

The girlfriend had called in a panic ― their pickup was dead, and Nathan Weston Sanders had collapsed. She couldn’t revive him and didn’t know where they were. Now, Sanders’ father and another man from the crayfish gathering were driving back into the fog to look for them.

An Improvised Response

Sheriff’s Officer Terry Gann was at a grocery store, taking a break from a long day working a double homicide when he received an EMS alert about a motorist who had a seizure due to a “green fog” crossing Route 433 east of the town.

“My friend, she’s laying on the ground, she’s shaking, she’s drooling out of the mouth”

Yazoo is Mississippi’s biggest county at 923 square miles, but it’s an economically disadvantaged one, with just 11 sheriff’s officers who get called in for everything from tornadoes and floods to industrial accidents. Even though he is the county’s only criminal investigator, Gann works the disasters too. At 7:32 p.m., he headed toward Satartia in his truck.

EMS advised responders that self-contained breathing apparatus was required to enter the “hot zone” inside the roadblocks, where the gas had settled. Gann didn’t have SCBA with him, but he went in anyway.

At the command post south of Satartia on Route 3, a man told Gann his daughter had gone missing in the gas plume, not far from the ruptured pipe. The cloud was moving slowly northwest, so first Gann took the road over the levee to enter the village from the south to evacuate any remaining residents.

He did a round of checks on houses, banging on doors and peering through windows, but found no one. Around him he saw ― and felt ― the cloud. “It’s like I just ran a mile as fast as I could. My ears were popping. My face was burning like a sunburn.”

His pickup also started to choke on the fumes. He raced back over the Yazoo River, out of the cloud, to catch his breath and get the vehicle running, then returned to check more houses. Just outside of town, he found a young man and woman pacing the middle of an intersection.

“It was almost like something you’d see in a zombie movie. They were just walking in circles,” he said. “I kept telling ’em, ‘Y’all get in the truck.’ And they would just look at me with this blank look on their face. And the girl was holding a phone up to her head but she wasn’t saying nothing. … Finally I just yelled at ’em, I said, ‘Get in the truck or you’re gonna die!’”

Gann shoved the dazed teenagers into the back seat, not knowing it was Nathan Weston Sanders and his girlfriend.

After picking up a woman he found unresponsive in a stalled car, his engine began sputtering again, so he returned to the command post to meet the ambulance. By the time they got there, Gann himself could barely breathe and had to be given oxygen.

He did one last search of Satartia, then messaged dispatch, “Everyone evacuated” at 9 p.m. He radioed that he was heading for Perry Creek Road, which hadn’t yet been searched.

That worried Jack Willingham, director of Yazoo County Emergency Management Agency, since Gann had been breathing high levels of CO2 for nearly two hours and was panting audibly over the radio. His speech was often slurred and when it wasn’t, it didn’t always make sense. Willingham ordered Gann to leave the “hot zone” immediately and get medical attention.

But Gann, disoriented by the lack of oxygen, got lost and never made it to Perry Creek. With radio guidance, he met an ambulance that took him to a hospital in Yazoo City. After two hours of oxygen treatments, he went home, utterly spent.

By then, however, a three-man team of Vicksburg firefighters was on its way to Perry Creek Road.

They were driving a UTV, or utility task vehicle, a small ATV-like two-seater with an open cargo bed in back that held spare air bottles and tools. Jerry Briggs, fire coordinator for Warren County, squatted in the cargo area with Warren County 911 director Shane Garrard, while Lamar Frederick, a Vicksburg fire chief, drove. Each wore 60 pounds of fire protective clothing and gear, including SCBA.

After making their own fruitless search of the village, they decided that rather than return empty handed, they would enter the blast area via Perry Creek Road. The roar of the ruptured pipeline was deafening as they approached.

A half mile up Perry Creek Road, they saw a car with its lights on and windows up just as the UTV began stalling.

“We got victims,” Frederick yelled above the roar.

Inside the small red Cadillac sedan were three men: DeEmmeris and Andrew Burns, and Victor Lewis. DeEmmeris Burns lay across the backseat in the fetal position. The other two were slumped against the windows, white foam coming out of their noses and mouths, their clothes stained with urine and excrement. The firemen thought they were too late.

The doors were stuck, so Briggs smashed the right rear window. The three were still breathing, though just barely. The rescuers shook them and tried sternum rubs, but got no reaction.

Panting in exhaustion and sweating under all their gear, they managed to get all three out and cram them into the UTV.

They headed toward the south command post. After a few minutes of fresh air, the victims began to stir. Then they tried to stand up. They seemed about to fall off when a truck full of county deputies met up with the UTV, and one of the deputies bear-hugged the men into place until they met the ambulance.

The firemen had just a few minutes to breath fresh air and chug water before Willingham sent them to evacuate a group of mostly elderly residents just across the river. Willingham and the National Weather Service office in Jackson were tracking the plume as it headed northwest, and Willingham was determined to get ahead of it.

By now, six Denbury officials had arrived on the scene along with Denbury’s air monitoring contractor, the Center for Toxicology and Environmental Health; the environmental remediation firm E3; an investigator for the federal Pipeline Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA); and officials from the Mississippi’s Emergency Management Agency and Department of Environmental Quality.

At 11:06 p.m., the Denbury team “observed no product coming from the failure location,” according Denbury’s report to PHMSA. The leak was officially declared over.

A Massive Buildout

Once the province of a few policy wonks and coal companies, shipping carbon dioxide and storing it underground has gotten much more mainstream attention in recent years amid a tsunami of conferences, draft legislation and interest groups.

The fossil fuel industry has gotten behind CCS as a technology that, it hopes, would allow continued production so long as the emissions are buried underground. But the immense network of pipelines needed to transport carbon dioxide to locations where it would be stored deep below ground weren’t discussed publicly until recently, nor was how such a rapid, unprecedented pipeline buildout could be done.

A much-touted December 2020 Princeton University study ― funded in part by the oil industry ― calls for a 65,000-mile system by 2050, which means adding 60,000 miles to the current 5,000 miles of CO2 pipeline. The new system would be organized into a spider web of continent-spanning trunk lines as large as 4′ in diameter — twice the size of the Satartia pipeline — fed by a system of smaller spur lines.

But even 65,000 miles of pipeline could only move 15% of current U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. To have any effect on climate change “would entail CO2 pipeline capacity larger than the existing petroleum pipeline system,” which totals 2.6 million miles, according to a 2020 study in Biophysical Economics and Sustainability.

Beginning with the Bush administration, the U.S. government has spent over $8 billion to promote carbon capture and storage (CCS). But almost all of the CO2 in current pipelines is used for enhanced oil recovery rather than being injected deep into the earth for secure geologic storage, and enhanced oil recovery produces more emissions than it sequesters. Almost none of today’s CO2 is manmade, but comes from natural sources like the Jackson Dome.

Proposals like Princeton’s would likely require extending CO2 pipelines into heavily populated areas, across mountains and other natural barriers. The cost of such an enormous system is driving some to suggest simply repurposing existing natural gas pipelines to move CO2.

But because CO2 is corrosive and will eat through the carbon steel used in petroleum pipelines if contaminated with even small amounts of water, CO2 pipelines have to be manufactured to a higher standard and the purity of the gas carefully monitored. And research shows that CO2 from a commonly used carbon capture technique is particularly likely to have water in it. CO2 pipelines also run at significantly higher pressures than natural gas pipelines, which in turn requires more energy-gobbling compressor stations along the line to keep the CO2 in a liquid state.

That’s why a 2019 National Petroleum Council report warned against using existing natural gas pipelines to move CO2. The American Petroleum Institute has also highlighted the risks.

Yet an influential white paper produced jointly by the Energy Futures Initiative, headed by former U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz, and the AFL-CIO proposes doing just that. “Repurposing the expansive U.S. network of existing oil and gas pipelines presents a ripe opportunity to lower costs for CO2 transport,” said the report. ![]() and we have learned all too well by now that oil and gas companies and their enablers (regulators, politicians, and too many lying lawyers and judges) appear to only care about money and power, and more money and power, and not give a shit about multinationals harming or killing humans or other species except to cover-it up, defame and or blame the harmed/dead.

and we have learned all too well by now that oil and gas companies and their enablers (regulators, politicians, and too many lying lawyers and judges) appear to only care about money and power, and more money and power, and not give a shit about multinationals harming or killing humans or other species except to cover-it up, defame and or blame the harmed/dead.![]()

Moniz was Biden’s energy adviser in his 2020 presidential campaign, and oversaw billions in spending on CCS in his time at the Department of Energy. He and his team are considered leading experts on both natural gas and carbon dioxide infrastructure. Yet the petroleum industry’s own longstanding warnings about mixing gas technology with carbon dioxide are nowhere to be found in a 79-page report or its 299 footnotes.

“So much of it is about cost cutting, finding ways to do things cheaper and where can you make compromises,” said Carroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environmental Law and co-author of a highly critical report on CCS and pipelines.

Muffett noted that CO2 behaves differently from natural gas inside a pipeline — in ways that make a CO2 rupture uniquely dangerous.

“Because of the intense pressures involved, explosive decompression of a CO2 pipeline releases more gas, more quickly, than an equivalent explosion in a gas pipeline,” noted a report by CIEL and the Environmental Working Group, and “even a modest rupture can spread freezing CO2 over a wide area within seconds.”

A complicating factor in the Satartia accident was the presence of hydrogen sulfide. A Mississippi Emergency Management Agency email from the night of the accident said the leak contained an “unknown amount of pressurized CO2 with H2S.” CO2 is often contaminated with hydrogen sulfide, and Muffett points out that not only does H2S increase the corrosiveness of CO2, but it has serious health effects that can include damage to the nervous system, lungs, liver and heart.

Even CO2 by itself, however, can be quite lethal. On a summer day in 1986, a thick plume of CO2 from a volcanic lake in Cameroon killed 1,746 people. Birds dropped out of the sky and whole families died together in minutes.

Short of death, however, there is a wide range of CO2 inhalation effects, which include dizziness, headache, nausea, shortness of breath, increased heart rate, memory disturbances, lack of concentration, disorientation, convulsions, and unconsciousness ― symptoms that closely track those of Satartia’s gassing victims.

Unfortunately, few emergency rooms are familiar with the range of its effects.

A Scramble At The Hospital

When DeEmmeris Burns woke up, he was sitting in a chair near a nurse’s station. He had no idea how he got to the hospital.

An IV was running down his arm, and his brother and cousin were in adjoining chairs. His lungs burned and his head ached. He was still in his soiled clothes.

“They didn’t put us in rooms. I mean, it was just all bad,” he remembered. “The nurses weren’t prepared for this.”

The hospitals told HuffPost that they responded appropriately under standard protocols for a mass toxic incident, but would not comment on specific cases.

At around 12:30 a.m., Sarah Belk, who had grown up with the Burns brothers, found the three sitting in chairs, wrapped in a single blanket. Belk had brought her own mother and daughter to the ER after they escaped from Sataria.

“I felt that they were not realizing the extent of what was going on with these people,” she said.Sarah Belk

Andrew Burns asked where they were, and she told them they were at the hospital in Vicksburg, that their car stalled in the cloud of gas, and they’d been found unconscious. They were shivering “like they were in shock,” Belk said.

She saw their stained clothes and the dried foam on their faces. All three were thirsty. No one was attending to them, and the nurses seemed dismissive and rude, Belk said.

“I felt that they were not realizing the extent of what was going on with these people,” she said.

Belk’s 16-year-old daughter, Ellie, had thrown up, and was still red-faced from the lack of air during her escape from Satartia. Belk’s 57-year-old mother, who has COPD, was also struggling to breathe, and after more than an hour of gas exposure, her complexion “was gray.” But Belk said she still struggled to get them oxygen or basic attention. The hospital seemed overwhelmed.

Belk let the three men borrow her phone to call their families.

“I’m like, ‘What’s going on?’” Berneva Lewis, Victor Lewis’ mother, remembered. “‘We’re at the hospital.’ That’s all they could tell me on the phone. I’m like, ‘What happened?’ They’re like, ‘They said we were in gas.’”

Given how disoriented they were, Lewis was startled to get a call at 2 a.m. saying the men were being released. “It was ridiculous. They were out before I could even get to the hospital,” she said.

Another relative picked them up at the hospital and drove them to Victor Lewis’ father’s home in Vicksburg. They were still in the same clothes they’d worn upon arrival.

Of some 49 gassing victims who went to the hospital, almost all were treated at Merit Health River Region in Vicksburg or Baptist Memorial Hospital in Yazoo City. But the victims say neither facility seemed prepared for how to deal with this kind of disaster. In response to questions from HuffPost, both hospitals acknowledged they based treatment on standard toxic event protocols, which included setting up unheated outdoor decontamination tents to undress and wash victims ― despite temperatures in the low 40s that day.

Neither hospital said they’d received any special training in handling a CO2 pipeline incident. Medical records for four gassing victims treated at Baptist Memorial — and for six of those from Merit River Region, including the Burns brothers and Lewis — seem to reflect confusion about what they were exposed to.

“Asphyxiation by environmental toxic gas, accidental or unintentional initial encounter. CO2, H2S, chlorine gas exposure from ruptured gas line,” reads the report for all four of the Baptist patients. Later the records cite “natural gas exposure.”

“They [were] nowhere near ready for something like that to happen,” Hugh Martin said. “They were understaffed, but they also didn’t know what the hell they were dealing with.”

For Denbury, An “Incident” Without Consequences

Denbury knew about the accident before anyone. At 7:07 p.m., a low pressure alarm at its Texas headquarters alerted the company that the pipeline was leaking, and the company closed the main operating valves for the Satartia section of the line at 7:15 p.m., according to Denbury’s incident report to the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA).

The report claimed that the company promptly notified local emergency responders, but both Fire Chief Durward Pettis and county Emergency Management Director Jack Willingham said nobody called them.

Denbury had no contact with them until Pettis called the company at about 7:45 p.m., according to the Yazoo County emergency dispatch log, and even then provided no guidance on the response or how to treat CO2 inhalation victims.

Without that guidance, 911 operators told callers there had been a natural gas pipeline rupture. But natural gas and CO2 are quite different. Natural gas is lighter than air, travels straight up, and is highly flammable. Exposure to CO2 mixed with hydrogen sulfide, on the other hand, can cause death from asphyxiation as well as lung damage. ![]() “Natural” gas, methane, can also and has killed by asphyxiation.

“Natural” gas, methane, can also and has killed by asphyxiation.![]() Residents of Sartaria were given no information about how to respond to such a mixture.

Residents of Sartaria were given no information about how to respond to such a mixture.

In the weeks that followed, Denbury also appears not to have disclosed the extent of the pipeline breach to investors.

“The affected pipeline segment was [isolated] within minutes of detection,” Denbury’s Senior Vice President of Operations David Sheppard said during a Feb. 25 quarterly earnings call. “And as a precaution, the area surrounding the leak site was evacuated, including residents of the small nearby town of Satartia. No injuries to local residents, our employees, our contractors were reported in association with the leak.” ![]() !!!!!!!!!

!!!!!!!!!![]()

Yazoo County Emergency Management Agency/Rory Doyle for HuffPost

To date, that is Denbury’s most detailed public statement on the CO2 pipeline leak. Its filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission make no mention of a pipeline accident or leak, the evacuation, the injuries to residents, or any other details. Its 2021 annual report made two oblique references to the explosion, noting an oil production decline in 2020 at its Delhi, Louisiana, oil field “due to the lack of CO2 purchases between late-February and late-October 2020 as a result of the Delta-Tinsley CO2 pipeline being down for repair during that period” and “$4.3 million of costs associated with the Delta-Tinsley CO2 pipeline repair.”

Denbury did disclose a total of 46 hospitalizations and 200 evacuees — the latter a little lower than the number reported by other sources — in its incident report to PHMSA.

Denbury also did not disclose that on Oct. 7, 2020, there was another accident while reconnecting the damaged pipeline section. While workers did a “controlled blow-down” to remove any remaining CO2 from the section, a valve “froze in the open position due to internal ice formation” and gas poured out, according to Denbury’s report to the state Department of Environmental Quality. Multiple attempts to close it failed, and some residents had to be evacuated that night on short notice. But the second incident lasted longer ― almost an entire day― and released 41,000 barrels of CO2, according to Denbury, while the Feb. 22 incident lasted four hours and released 31,407 barrels.

Why the pipeline initially ruptured also has yet to be determined. A PHMSA spokesman declined to comment on when its official report on the incident might be released.

Meanwhile, Denbury sent a section of the pipeline to a metallurgical lab for testing. Based on those findings and its contention that the pipeline was “code compliant,” it theorized in its report to PHMSA that soil movement caused by persistent heavy rains “induced axial stresses” that caused a rupture.

Rory Doyle for HuffPost.

Heavy rains beginning in late January 2020 did cause widespread flooding and evacuations along the Yazoo and Mississippi rivers. But Chad Jones, a plaintiff’s lawyer representing gassing victims who is also a geologist, said flooding is common in the Delta, and should have been anticipated when the pipeline was built in 2007. Jones noted several other factors that should have been taken into account during construction as well: the soil in the area, called loess, is unstable and prone to shifting and mudslides, and building a pipeline through such soil requires special techniques because any rupture in that area would send the gas downhill into Satartia.

“They might claim an act of God,” said Jones, “but I mean, we can prove that it wasn’t.” ![]() If he doesn’t betray his clients, like my lying ex lawyers, Cory Wanless and Murray Klippenstein, did to me.

If he doesn’t betray his clients, like my lying ex lawyers, Cory Wanless and Murray Klippenstein, did to me.![]()

Denbury Resources filed for bankruptcy five months after the incident, citing the pandemic crash in oil prices. It emerged from Chapter 11 in September 2020 after shedding $2.1 billion in debt and its old name. In March 2021, the newly restructured Denbury Inc. gave a presentation at the 26th Annual Credit Suisse Energy Summit recounting highlights of 2020, including “record levels of safety performance for the fourth consecutive year.”

Among the new capital investments for 2021 that Denbury CEO Chris Kendall and other officials unveiled was a $7 million plan boosting CO2-based drilling operations in the Tinsley field — using the same pipeline that ruptured in 2020.

The Next Day

Officer Terry Gann got three hours of sleep before heading back to Satartia.

Abandoned vehicles were everywhere ― doors ajar, many with their windows smashed from the rescue efforts. Gann had the keys to several, and rescuers set up a kind of lost and found on the side of the road.

Gann helped Denbury personnel, including technicians with gas measuring equipment, escort villagers back to their homes. The rotten egg odor was still heavy in the air.

As soon as Linda Garrett and her family walked in her kitchen door, the technician’s gas meter hit the red zone, and they had to leave until levels went down.

That evening, Satartia Mayor Kathy Nesbit, Pettis and several Denbury representatives presided over a standing-room-only meeting at First Baptist Church. Bruce Augustine, Denbury’s operations manager, told the crowd that the company was “very happy that the air monitoring we’ve done shows that everyone can now return to their homes.”

Denbury officials said they would be stationed at the town hall to deal with any problems or complaints, and that residents would be promptly reimbursed for medical bills. While there was some discussion of safety measures to prevent a repeat disaster, nothing definite was promised.

Nesbit, an intensive care nurse who had been working at River Region hospital the night before, tried to dispel fears of long-term health effects. “It is a natural chemical in our bodies,” she said. “So it’s not a poison that’s going to infiltrate you and eventually kill you.”

That was cold comfort to many survivors, some of whom noted pointedly that Nesbit hadn’t been in town that night and didn’t experience being inside the plume.

When it was over, Thelma Brown and Berneva Lewis thanked Vicksburg firefighters Jerry Briggs and Shane Garrard for saving their sons. “That was when they actually told us about the condition that the guys were in and how they were very near death and foaming at the mouth,” Brown said.

DeEmmeris and Andrew Burns and Victor Lewis were still in no shape to go to any meetings. After a sleepless night, more vomiting and severe headaches, they spent early Sunday on oxygen, being monitored and having bloodwork done at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, the state’s flagship teaching hospital. Even after that, Lewis told his mother, who is a nurse, that he still felt terrible.

She took all three to another doctor the next day, and tests revealed that their blood CO2 levels were still alarmingly high. The doctor said they would need to remain on oxygen until the numbers came down, and sent them to a pulmonologist.

Denbury called victims to ask whether they needed anything and reimbursed medical bills quickly. Residents were asked to drop by Town Hall to discuss compensation for other losses, like pain and suffering. Those who accepted were paid on the spot, but waived their right to sue or discuss the settlement.

But many victims, some of whom say they are still sick, anxious and unable to fully return to their previous lives, weren’t interested in a deal and decided to sue. The Burns brothers and Lewis hired Robert Gibbs, a well known lawyer from Jackson. Their suit will claim Denbury failed to properly maintain the pipeline or take necessary safety precautions to prevent exposure to hazardous gas, Gibbs said.

Another who decided to sue was Martin, whose occasional breathing difficulties from mild COPD have required much more frequent use of his inhaler since the February 2020 incident.

Medical records also show that months after the incident, his 78-year-old mother, who had no previous history of breathing difficulties, was using albuterol constantly, getting oxygen treatments, and had to be hospitalized for a week in March 2020 after he found her lying unresponsive in bed and having trouble breathing.

Marguerite Vinson was frustrated that not only was she not recovering, she seemed to be getting sicker.

“I can’t think half-right! And I just wear out. Anything I try to do, it’s hard to do if it requires exertion,” she said.

Linda Garrett said Denbury asked to meet with her three weeks after the incident and offered her a package deal — $5,000 each for her, her daughter and granddaughter, which she refused. She said she heard one neighbor, who is white, had been offered $10,000, and that another white neighbor had been given $18,000 compensation for cows that miscarried after the incident.

“They value a cow more than they do a human,” Garrett said.

Gibbs’ three clients, however, did get some extra attention from Denbury.

Not long after the gassing, DeEmmeris Burns’ phone rang. According to Burns, the voice on the other end identified himself as Denbury CEO Chris Kendall.

“He asked me ‘How’s everything going?’” said Burns. “I just told him I’ve got someone talking for me now.”

“You Should’ve Told Us.”

Over a year and a half after the gassing incident, the Burns brothers and Lewis still have not returned to work. They were under a doctor’s care until February 2021, when they were taken off oxygen, said Gibbs. DeEmmeris Burns moved out of his mother’s house because, he said, it’s too painful for him to drive up Perry Creek Road.

Gibbs said his and some nine other law firms representing the Satartia CO2 plaintiffs have joined forces as the Denbury Litigation Group. While Gibbs represents only the three Perry Creek Road victims, some lawyers have as many as 60 or 70 clients. None has yet filed suit, awaiting the long-delayed Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration report on the reasons for the accident.

Martin said he hopes a lawsuit will pry out all the facts about what happened that night and why.

“If there’s this many malfunctions in that one section of pipeline, somebody was at fault, or they were passing inspections they shouldn’t have passed,” said Martin. “That’s what we need to find out.”

Nevertheless, opinions differ as to how or even whether Denbury should be held accountable. One reason may be an inherent reluctance to criticize the oil and gas industry, a source of scarce well-paid jobs as well as a statewide political power. Some are willing to consider the pipeline rupture “an act of God,” though gassing victims point out that many who believe that were not in town the night of the disaster.

Rory Doyle for HuffPost

Interestingly, only a few of the residents interviewed for this article had heard of carbon capture and sequestration ― and none knew about plans for a greatly expanded CO2 pipeline network.

“That doesn’t make any sense,” said Martin. “Not when they can’t control what they’ve already got. I think there’s real basic questions that need to be answered first.”

Linda Garrett said she still struggles with back pain from carrying Makaylan to the car that day. Makaylan’s asthma, which had been in remission, is worse than ever, and both her daughter and granddaughter remain traumatized. She wants the company punished.

Denbury, she said, should have warned the town before there was an emergency. ![]() but, oil and gas and frac companies rarely, if ever, do. Most don’t give a shit who they kill (even their workers) or how many investors they steal from with their lies. Encana/Ovintiv was required under AER rules to consult, assess cumulative impacts and warn my community that our drinking water supply was under seige; the company only consulted with lies after the law violations, followed by more lies and law violations by our regulators and more lies by politicians/judges to enable the company and its enablers.

but, oil and gas and frac companies rarely, if ever, do. Most don’t give a shit who they kill (even their workers) or how many investors they steal from with their lies. Encana/Ovintiv was required under AER rules to consult, assess cumulative impacts and warn my community that our drinking water supply was under seige; the company only consulted with lies after the law violations, followed by more lies and law violations by our regulators and more lies by politicians/judges to enable the company and its enablers.![]()

“If you cared about us, you and the pipeline, you should have let us know,” Garrett said. “But you didn’t let us know nothing. You just telling us now. That doesn’t seem right to me. Sometimes we have to be held accountable for the things that happen.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article misidentified a person affected as Lynett Burns. The woman’s name is Lynett Garrett.

Ottawa missing out on benefits of enhanced oil recovery, Saskatchewan says by Emma Graney, Sept 7, 2021, The Globe and Mail

The federal government is being “willfully blind” by ignoring the economic and environmental opportunities of including enhanced oil recovery in its planned carbon-capture tax credit, according to Saskatchewan Energy Minister Bronwyn Eyre, who was speaking ahead of the release of the province’s own carbon-capture strategy.

Enhanced oil recovery, or EOR, is a process in which carbon-dioxide gas is injected underground in order to draw oil to the surface. An advantage of EOR is it can be used to extract oil from petroleum reservoirs that have already been pumped so thoroughly that they no longer yield easily to other methods.

April’s federal budget included plans for a carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) tax credit, which would reward investment in technologies that sequester carbon-dioxide emissions before they can be released into the atmosphere. But unlike a similar mechanism in the United States, Canada’s proposed tax credit specifically excludes projects that would include an EOR component.

“Enhanced oil recovery is a major part of the mix for us. It’s an absolute win-win in terms of the economy,” ![]() but dangerous and dreadful for communities, landowners, taxpayers and the environment

but dangerous and dreadful for communities, landowners, taxpayers and the environment![]() Ms. Eyre said in an interview.

Ms. Eyre said in an interview.

The U.S. program has worked well because it’s an all-encompassing tax credit, she said, “not one that ignores the oil part.”

On Tuesday, Ms. Eyre will unveil Saskatchewan’s new CCUS strategy, which will guide the province’s push to attract $2-billion in private-sector investment in the technology.

The minister would not share details on the new strategy before its release, but she said it would focus on altering regulations and extending current infrastructure investment incentives ![]() Translation: Deregulate to enable injection free for alls, and steal more of our tax dollars to gift to billion dollar profit raping polluters destroying earth’s ability to sustain life

Translation: Deregulate to enable injection free for alls, and steal more of our tax dollars to gift to billion dollar profit raping polluters destroying earth’s ability to sustain life![]() to attract carbon-capture projects to the province.

to attract carbon-capture projects to the province.

She said Saskatchewan will also look at ways CCUS infrastructure can bolster opportunities for hydrogen production.

Ms. Eyre said the province’s oil revenue is already seeing a recovery, in part because of EOR projects near Lloydminster, a city that straddles the Saskatchewan-Alberta border. Ignoring that kind of economic and emissions-reduction ![]() and other harms increase

and other harms increase![]() potential in a tax credit means Ottawa is sticking its head in the sand, she said.

potential in a tax credit means Ottawa is sticking its head in the sand, she said.

“You can’t be so willfully blind to something that actually works and is an actual solution,” she added. ![]() yes, we can, notably when it’s oil, gas and frac patch corporate welfare that increases pollution and puts lives at risk.

yes, we can, notably when it’s oil, gas and frac patch corporate welfare that increases pollution and puts lives at risk.![]()

Forcing carbon-dioxide emissions deep into the ground as part of an EOR process prevents them from entering the atmosphere, where they could contribute to climate change.

EOR is only one use of captured carbon. The captured greenhouse gas can also be used in other major industrial sectors, such as power generation and manufacturing.

Groups such as the International Energy Agency say CCUS is an important part of reducing global greenhouse gas emissions. But many environmental groups argue that using captured carbon in EOR increases oil production, which in turn increases the total output of carbon emissions.

Several projects already capture carbon in Western Canada. For example, Shell’s Quest facility, near Edmonton, has captured and stored more than five million tonnes of carbon dioxide since it began operations in 2015.

But Alberta Premier Jason Kenney said earlier this year that Canada risks falling behind as a leader in carbon capture if Ottawa doesn’t make significant strides to increase investment in the emissions-lowering technology. The province asked the federal government to commit to $30-billion in spending or tax incentives over the next decade, in order to spur investment in large-scale industrial carbon-capture projects.

Ms. Eyre will announce details of Saskatchewan’s new CCUS strategy near the southern city of Weyburn, at an EOR facility operated by Whitecap Resources Inc. The site uses carbon dioxide purchased from the coal-fired Boundary Dam Power Station in nearby Estevan, and also from a coal gasification project in North Dakota.

Saskatchewan’s new CCUS strategy will be released ahead of the 2021 Energy and Mines Ministers’ Conference in Saskatoon, which will take place later this week.

Refer also to:

2021: Cenovus completes Husky acquisition, swallowing Saskatchewan’s historically largest oil producer

… Cenovus had recently exited Saskatchewan, with its $940 million sale of its controlling interest in the Weyburn Unit to Whitecap Resources in 2017, part of its efforts to finance the $17.7 billion purchase of ConocoPhillip’s 50 per cent interest in jointly owned oilsands venture and deep basin conventional assets, announced earlier that year. Its acquisition of Husky marks Cenovus’ return to Saskatchewan in the biggest way possible, buying the province’s historically largest producer. In 2009, the Cenovus was spun out of EnCana, with Cenovus taking over the major oil plays, including the Weyburn Unit, and Encana focusing on natural gas. EnCana had previously been PanCanadian until 2002. PanCanadian’s roots, as a division of Canadian Pacific Railways, went back as far as the 1880s, with the discovery of natural gas near Medicine Hat. In 1954, the discovery well of what would eventually become known as the Weyburn field was drilled near Ralph by Central Leduc Oils Ltd., a company which became Central Del Rio Oils Ltd. in 1957 with the merger of Del Rio Oils. The discovery well at 14-7-7-13-W2 came in during the fall of 1954. According to PetroleumHistory.ca, “Central-Del Rio was purchased by Canadian Pacific Oil and Gas in 1969. However, the company continued to operate under the Central-Del Rio name until 1971 when its name changed to PanCanadian Petroleum Limited. “PanCanadian was purchased by Alberta Energy Company in 2002 and became EnCana. Later EnCana was split into EnCana and Cenovus.”

Carbon dioxide enhanced oil recovery

As PanCanadian, then EnCana and Cenovus, the Weyburn Unit pioneered deployment of carbon dioxide enhanced oil recovery (CO2-EOR) in Canada, starting in 2000. A few years later, Husky developed its own flavour of CO2-EOR, including producing CO2 at the upgrader. They have three pilot projects for CO2-EOR in place. …

Canada’s poster child for so-called clean energy and “the world’s first CO2 Measurement, Monitoring and Verification Initiative” may have sprung a serious leak in Saskatchewan.

And it’s the sort of geological and political disclosure that just might unravel plans to spend billions of taxpayers’ dollars on constructing elaborate carbon cemeteries across the country, if not the world.

The story, which includes explosions, dead animals, and an international cast of characters, also raises some critical questions about transparency and the quality of government regulation in a carbon-centric economy.

… At the time EnCana Corporation (now Cenovus Energy) had started to flood the aging crude field with gallons of salt water and tonnes of CO2 piped from a North Dakota coal gasification plant nearly 320 miles away.

In 2004 the IEA declared that Weyburn was a “highly suitable for the secure long-term storage of CO2” and it could hold up to 55 million tonnes of CO2. But the site would have to be monitored for 5,000 years.

Computer risk models also predicted that CO2 would never leak into “either potable water zones closer to the surface or ground surface above the storage reservoir.” …

Both the IEA and PTRC, a research group funded by government and the oil patch, also released a 283-page study in 2004 claiming there were no leaks to date and that storing carbon underground could play an important role in “tackling climate change.” No real monitoring data on the project has since appeared in the public domain.

Around the same time Cameron and Jane Kerr, who own nine quarters of land in the midst of the project, started to notice some leaks. …

In 2003 the Kerrs dug a gravel pit to service EnCana’s oil roads. After the pit promptly filled with water, the Kerrs observed strange doings including foaming, discolouration and hissing bubbles. They also discovered the carcasses of dead ducks, a rabbit and a goat by the pit.

When several gaseous explosions rocked the pond in 2007, the couple moved to Regina. “We have a problem and no [one] wants to properly investigate it,” Jane Kerr told Canadian Business at the time.

Although the Saskatchewan government promised to do a year-long study on the farm’s air, water and soil, the Kerrs say it never happened. What they got instead were a few ad hoc day-long tests and nothing more.

….the Kerrs then hired Paul Lafleur of Petro-Find Geochem to do some serious monitoring.

Unlike so-called government and industry experts intent on declaring the safety of carbon cemeteries before the evidence is in, Lafleur found lots of CO2.

Using tried and true carbon sensors designed to detect oil deposits, Lafleur discovered dangerously high concentrations of the gas on the Kerr’s property.

Seeping dangers cited

In one location alone Lafleur detected concentrations as high as 110,607 parts per million (ppm), twice the amount needed to asphyxiate a person. Near the Kerr’s home he also recorded concentrations of 17,000 ppm, a level “that far exceed the threshold level for health concerns.”

As a consequence “CO2 could enter the home in dangerous concentrations through the crawl space due to negative pressures caused by a natural gas heating furnace.”

Given that Cenovus’s closest injection well lies a mile away from the Kerr home, Lafleur concluded that the CO2 was probably seeping through open fractures and faults that intersect the Weyburn field. In other words, there were cracks in the cemetery.

In addition a Saskatchewan lab confirmed that the CO2 found at Kerr’s place clearly originated from “the CO2 injected into the Weyburn reservoir.” …

Now Rhona Deflrari, a spokesperson for Cenvous, say the Kerrs are well known to the company and that the oil company has hired three experts to pour over the LaFleur report. ![]() The blame nature kind of experts Encana/Cenovus/Ovintiv likes to have in their back pocket to do the Hanky Panky?

The blame nature kind of experts Encana/Cenovus/Ovintiv likes to have in their back pocket to do the Hanky Panky?![]()

However she emphatically adds that, “There is no evidence that any activity of Cenovus has done any harm of any kind to the Kerr’s property.”

The Petroleum Technology Research Centre says the same thing. It promises that “a response to this report will be provided once it has been thoroughly reviewed.” …

The Kerrs aren’t the only folks asking tough questions about carbon storage these days. In recent months scientists have raised serious concerns about the efficacy of burying massive amounts of carbon underground.

At Duke University, for example, researchers reported that CO2 leakage would not only acidify groundwater but mobilize heavy metals such as iron and zinc and thereby contaminate local aquifers. (Tests on water from the Kerr property have found high levels of acidity and heavy metals too.)

Last month the Stanford University geophysicist Mark Zoback challenged the viability of large-scale carbon cemeteries altogether. He concluded that the injection of vast volumes of CO2 underground could trigger small earthquakes that could in turn create fractures like those in the Weyburn field.

“While the seismic waves from such earthquakes might not directly threaten the public, small earthquakes at depth could threaten the integrity of CO2 repositories expected to store CO2 for periods of hundreds to thousands of years,” stated Zoback.

Reduce or sequester?

Last but not least a Danish researcher reviewed the potential for leakage and concluded that the “dangers of carbon sequestration are real and the development of this technique should not be used as an argument for continued high fossil fuel emissions. On the contrary, we should greatly limit CO2 emissions in our time to reduce the need for massive carbon sequestration.”

Cameron Kerr, a plain-talking farmer, hasn’t read all these studies. But he does have one word of advice for Alberta which plans to bury millions of tonnes of CO2 under farmland throughout the province at a cost of $1 billion to $2 billion a year.

“Don’t let it happen. Shut it down now. You’ll have no different response from government than we got. And you’ll waste lots of taxpayers’ money.”