2015 06: FINAL SUPPLEMENTAL GENERIC ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT

ON THE OIL, GAS AND SOLUTION MINING REGULATORY PROGRAM Regulatory Program for Horizontal Drilling and High-Volume Hydraulic Fracturing to Develop the Marcellus Shale and Other Low-Permeability Gas Reservoirs by New York State DEC:

High-volume hydraulic fracturing is defined as the stimulation of a well using 300,000 or more gallons of water as the base fluid for hydraulic fracturing for all stages in a well completion, regardless of whether the well is vertical or directional, including horizontal.

***

Hydraulic Fracturing Definition Reality Check:

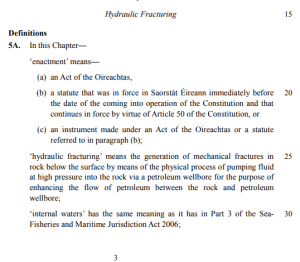

Republic of Ireland’s Legislated Frac Ban Definition of frac’ing:

End Hydraulic Fracturing Definition Reality Check.

***

The 300,000-gallon threshold is the sum of all water, fresh and recycled, used for all stages in a well completion. Well stimulation requiring less than 300,000 gallons of water as the base fluid for hydraulic fracturing for all stages in a well completion is not considered high-volume, and will continue to be reviewed and permitted pursuant to the 1992 GEIS, and 1992 and 1993 Findings Statements. Wells using less than 300,000 gallons of water for hydraulic fracturing per completion do not have the same magnitude of impacts. Indeed, wells hydraulically fractured with less water are generally associated with smaller well pads and many fewer truck trips, and do not trigger the same potential water sourcing and disposal impacts as high-volume hydraulically fractured wells. The 300,000-gallon threshold also applies if a re-completion of an existing well involves hydraulic fracturing using 300,000 gallons or more of water for the re-completion. The 300,000-gallon threshold is calculated based on all stages per well completion or well re-completion, not cumulative use for separate completions or re-completions.

***

Governor Cuomo announces permanent ban on hydrofracking in New York by queenseyes, January 22, 2020, Buffalo Rising

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo has announced that he will incorporate legislation in the Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Executive Budget permanently banning fracking [But, unless he fixes the definition, only some water fracs will be permanently banned] in New York. Cuomo stated that the temporary ban that is currently in place has not only been prudent, it has also proved that there are cleaner and more sustainable alternative energy options available, which can help to fuel the economy. The legislation would disallow the Department of Environmental Conservation from issuing permits to frackers, described as those who drill, deepen, plug back or convert wells that use high-volume hydraulic fracturing as a means to complete or recomplete a well.

“New York’s leadership on hydraulic fracturing continues to protect the environment and public health, including the drinking water of millions of people, and we must make it permanent once and for all,” Governor Cuomo said. “In the five years since fracking was banned, we have proven that it was in fact, not the only economic option for the Southern Tier. The region has since become a hotbed for clean energy and economic development investment through programs like 76West and Southern Tier Soaring, creating new good-quality jobs that pave the way for further growth.”

New York’s was the first ban by a state with significant natural gas resources.

Cuomo stated that the new legislation is part of the State’s efforts towards achieving its clean energy economy goals. Enhanced efforts are being made to further protect the environment from water and air pollution. As of 2015, The Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) embarked upon a 7 year study process, to determine the potential ill-effects on high-volume hydraulic fracturing in communities. Initially, it was a NYS Department of Health (DOH) that questioned the safety of fracking in 2014, when it was determined that research “found significant uncertainties about health, including increased water and air pollution, and the adequacy of mitigation measures to protect public health.” That questioning led to the 2015 ban on high-volume hydraulic fracturing, until further determinations could be made. Ultimately it was the DOH that called for the highly controversial drilling practice to be banned in perpetuity in NYS.

DEC Commissioner Basil Seggos said, “Governor Cuomo has detailed the biggest and boldest environmental agenda in the nation, and the permanent ban of hydrofracking is a critical part in ensuring the protection of water quality, transitioning from fossil fuels, and continuing our role as a climate leader. ”

Actor and environmental advocate Mark Ruffalo said, “I join with environmentalists, health experts, and New Yorkers everywhere in applauding Governor Cuomo for including legislation in the budget to make the fracking ban permanent law. The science overwhelmingly shows that fracking is disastrous for drinking water, public health, and climate change. Permanently banning fracking is what real environmental and climate leadership looks like.” [New York must repair their definition too.]

Refer also to:

2014: 89-34 vote! New York Assembly passes fracking ban; Senate hopes dim

2013: New York State Health Commissioner Nirav Shah cites ‘new data’ for fracking delay

2013: Chesapeake drops energy leases in fracking-shy New York, Frantic fracking sends US natural gas prices into freefall [yup, the oil and gas industry’s greed killed the industry’s golden eggs, and investors’ too!]

Yup, same problem everywhere they frac:

2013: New York State Elected Officials Raise Concerns About Fracking Costs

2012: Yoko Ono, Sean Lennon Put Anti-Fracking Message on New York Billboard

2012: Cuomo Resets New York Fracking Review, “Consigning Fracking To Oblivion”

2012: Fracking Conference to Focus on Law and Science in Light of Pending New York Ruling

… The 1999–2011 analysis of dissolved methane in groundwater in New York is meant to document the natural occurrence of methane in the States aquifers.

[Depths of the water wells sampled is critical information not included in this report, nor is distance of the water wells to the more than 75,000 oil and gas wells drilled in the state since the late 1800’s of which 14,000 are still active, or rates of methane leakage from those energy wells especially those abandoned and poorly plugged (estimated at about 4,800)]

2012: Yoko Ono, son Sean Lennon announce anti-fracking coalition of artists in New York

2012: New York State to allow fracking

2012: Lenape Resources Threatens Lawsuits Over New York Fracking Bans

2012: More Than 1,000 Businesses Demand a Fracking Ban in New York

2012: U.S. Says New York State Can’t Sue Over Fracking Regulations

2012: Judge to Rule on Whether New York Can Sue Over Fracking Regulations

2012 05 24 Jessica Ernst presents at Cortland Health Dept. New York

2012 05 21-24 Jessica Ernst presents at Elmira, Owego, Ithaca, La Fayette New York

2012 05 21 Jessica Ernst presents at Bath (Steuben County) New York

2012: The Fracking Industry’s War On The New York Times — And The Truth

2011: New York Comptroller DiNapoli Introduces Frack Fund To Cover Industry Damage

2011: Federal Government Asks Judge To Dismiss New York State Lawsuit

2011: Lawsuits Predicted as New York Towns Ponder Whether to Block Fracking

2011: Six frac firms hit with New York State subpoenas

2011 10 01: UNANIMA International Woman of Courage Award

NEW YORK, New York UNANIMA International, a UN Economic and Social Council accredited NGO working for international justice at the United Nations celebrates its 10th Anniversary Saturday by presenting its annual WOMAN OF COURAGE award to Jessica Ernst of Rosebud, Alberta, internationally known for her efforts to hold companies accountable for environmental harm done by “fracking”.

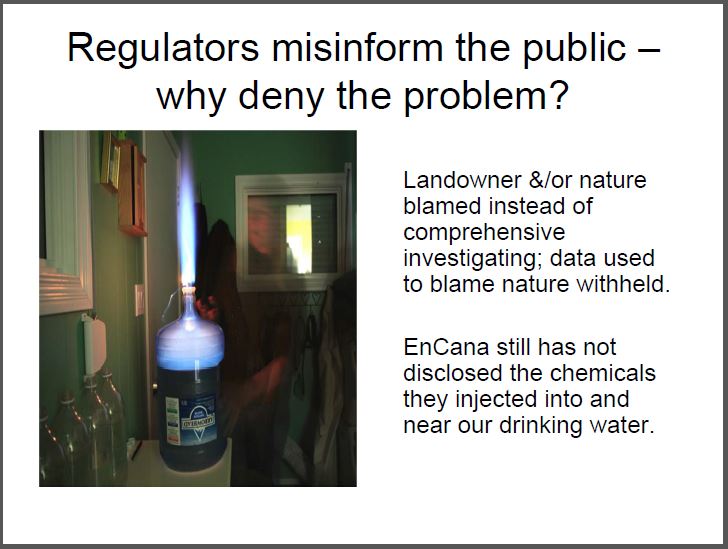

As usual, Encana (name changed to Ovintiv) lied to the media. Ernst presented Encana’s own data proving the company illegally frac’d Rosebud’s drinking water aquifers and diverted fresh water from them without the required permit under the Water Act.

Fast forward nine years to today, February 4, 2020, even with Ernst’s lawsuit and spending nearly $400,000.00 in legal fees and court costs, Ernst still has not received from Encana the chemicals injected into her community’s drinking water aquifers and many other documents relevant to her case, contrary to Alberta’s Rules of Court. The third case management judge on the case was picked by Encana and the Alberta government, and granted by the Court of Queen’s Bench. Will a company’s chosen judge make Encana heed the rules? Unlikely. Ernst expects him to punish Ernst instead.

2011 01 11: Ernst submission to New York State DEC

Jessica Ernst

Box 753 Rosebud, Alberta Canada T0J 2T0

To the NY Department of Environmental Conservation

Sent via http://www.dec.ny.gov/energy/76838.html

Frac’ing Inhumanity

I hiked in New York State most weekends in the fall as I was growing up in Quebec. I love New York. You have much to protect from the new brute force highly risky and toxic hydraulic fracturing. Please stop believing industry’s lies, promises and assurances. Please stand up to the corruption seething around the world, especially in our politicians and captured energy regulators and do the right thing – say no.

I am a scientist with 30 years experience working in Western Canada in the oil and gas industry. I am suing EnCana, the Alberta Government and energy regulator for unlawful activities (www.ernstversusencana.ca). Albertans are told we have the best in the world regulations and regulators. My statement of claim tells a compelling tale of drinking water contamination coverup and how even the best regulations and laws do not protect families, communities, water, lands and homes from hydraulic fracturing. I consider it part of this submission. It is available to the public on the case website at the above link.

I had an incredible supply of fabulous water. I miss it everyday. The new frac’ing is a global issue, a scary Hellish one. I live it; I’ve been a frac guinea pig for a decade.

The historic record (1986, attached after my submission) on my water well in a regulator commissioned report states: Gas Present: No. Prior to the arrival of experimental, brute force hydraulic fracturing (2001) in my community, only 4 of 2,300 historic water well records noted the presence of a gas that could be methane within about 50 square kilometers around my water well. After EnCana fractured my community’s fresh water aquifers, there was so much gas coming out of my well, it was forcing water taps open making them whistle like a train. Bathing caused incredibly painful caustic burns to my skin. As water wells went bad community wide, we got the same promises fractured communities get everywhere. For example: “We only fracture deep below your drinking water supply, deep below the impermeable layer to prevent gas from migrating into your water.” They reminded us that Albertans are blessed with “World Class, Best in the World” regulators and regulations, while quietly deregulating and taking our rights away to accommodate the inevitable frac impacts.

My water is too dangerous to be connected to my home; the isotopic signature of the ethane in my water indicates the contamination comes from EnCana’s gas wells. In 2006 in the Legislature, the Alberta government promised affected families a bandage – safe alternate water “now and into the future.” They broke that promise and ripped the water away. I drive more than an hour to haul safe water for myself.

I learned that when you’re frac’d, there’s no after care. What happened in my community is reportedly happening everywhere they frac, regardless of company or country. Affected citizens are abandoned.

Americans are fortunate to have the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and federal health officials (the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry) that warned Pavillion citizens to stop drinking the water. EnCana frac’d hundreds of metres more shallow around my well than the EPA reports the company did at Pavillion. EnCana was also stingy here with surface casing. Alberta’s regulator found much more methane in my water than the EPA found at Pavillion, and some of the same man-made toxics. Is that a frac coincidence?

And like at Pavillion, and in so many contaminated communities in the USA, the company still has not disclosed the chemicals they injected, and our regulators and governments refuse to make them. Hexavalent chromium was found in a regulator monitoring water well. The regulator didn’t share this with my community, it was gleaned it through my Freedom of Information request. In another regulator monitoring water well, they found no water, only methane and ethane – so much so that the gas was forcing the lid open – like the gas did to my water taps. Did they warn anyone? No. They commissioned reports that ignored the historic records and used unsubstantiated claims of gas in other water wells to blame nature.

I see no help from the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, American Petroleum Institute, Groundwater Protection Council or FracFocus and its newly released Canadian cousin by the British Columbia Oil and Gas Commission. I do not believe that multinationals keep chemical secret for proprietary reasons. I believe they keep them secret because companies know their drilling and frac’ing – waterless or not – is irreversibly contaminating groundwater, and they do not want us to be able to prove it.

Recently, EnCana drilled more gas wells around my home and under my land. I thought of farmers around the world as I watched EnCana dump their toxic waste on my neighbor’s crop land and pump undisclosed chemicals labeled flammable down their gas well to be fractured above the Base of Groundwater Protection near my home.

Even the best laws and regulations will not protect New York’s water and people from this arrogant, bullying, deceptive, uncooperative, “bad neighbour” industry. Shamefully, the revised draft Supplemental Generic Environmental Impact Statement (dSGEIS) on high-volume horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing is nowhere near O.K., never mind the best. I get “Best in the World.” What does New York get?

I’ve learned that frac’ing is hideous, but what follows reveals true inhumanity and greed. Please find my comments with supporting documents attached.

Thank you.

Sincerely,

Jessica Ernst, B.Sc., M.Sc.

Attachment:

1. Groundwater is a critical resource for nearly 600,000 Albertans and 10-million Canadians. Yet good data on aquifers and groundwater quality remains sparse. In 2005 Dr. John Carey, Director General of the National Water Research Institute, told the Standing Senate Committee on Energy, the Environment and Natural Resources that “We would not manage our bank accounts without monitoring what was in them.” Alberta and Canada now manage their groundwater this way.

Activities of the oil and gas industry greatly impact groundwater. According to a 2002 workshop sponsored by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, drilling sumps, flare-pits, spills and ruptured pipelines as well as leaky abandoned oil and gas wells can all act as local sources of groundwater contamination. Given that little is known about the long-term integrity of concrete seals and steel casings in 600,000 abandoned hydrocarbon wells in Canada, the study added that the industry’s future impact on groundwater could be immense. The paper concluded that unconventional natural gas drilling such as coalbed methane (CBM) posed a real threat to groundwater quality and quantity, and that the nation needs “baseline hydrogeological investigations in coalbed methane….to be able to recognize and track groundwater contaminants.” Not until nine years later on September 21 2011, did the Canadian government announce that it would initiate two reviews to determine whether hydraulic fracturing is harming the environment. These are not investigations or studies.

2. Recent government documents acquired under the Access to Information Act by Ottawa researcher Ken Rubin revealed that “Canadians are currently facing serious groundwater quality and availability issues…..There is no visible federal water policy agenda nor a common agenda for the whole country.” To date only three of eight key regional aquifers have been mapped and that only eleven of 30 key aquifers will be assessed for “volume, vulnerability and sustainability by 2010.” At this current rate of progress it will take another 28 years to develop a basic National Inventory of groundwater resources.

3. A 2007 review of Alberta groundwater programs by the Rosenberg International Forum on Water Policy declared Alberta’s groundwater policies “inadequate” and reported a “lack of comprehensive monitoring systems.” The report added that “exploitation of Alberta’s energy resources is proceeding at a pace much faster than had been anticipated” but that there had been no parallel acceleration in the protection of water resources. A monitoring network “is the last line of defense against contamination by industries that are essential to the economic future of the province.”

4. In 1987, the EPA documented that hydraulic fracturing by industry had contaminated groundwater. The New York Times’ Ian Urbina reported that many more cases were sealed by settlements and confidentiality agreements. In 2010, the Canadian oil and gas industry advertised: “Fact: Fracturing has not been found to have caused damage to groundwater resources” and EnCana advertised: “In use for more than 60 years throughout the oil and gas industry, there are no documented cases of groundwater contamination related to the hydraulic fracturing process.” Some companies and regulators continue to mislead the public, others have replaced the word “documented” with “proven” in their chant.

5. In the USA, by the early 1990’s numerous water contamination cases and lawsuits had sprung up in CBM development areas. “In a two-year study, USGS scientists found methane gas in one-third of water wells inspected and concluded that oil and gas drilling is the main source of contamination of the shallow aquifers in the Animas River Valley….Based in part on the USGS report, lawyers representing hundreds of area residents filed a class-action lawsuit Feb. 11 charging four oil companies – Amoco Production Company, Meridian Oil Inc., Southland Royalty Company, and Phillips Petroleum – with recklessness and deliberate disregard for the safety of local residents. The suit says the four oil companies ignored their tests, which showed that methane from their deep wells was polluting shallow aquifers, and asks for both actual and punitive damages.”

6. Industry and the Alberta government have reported leakage of gas and other contaminants into groundwater and atmosphere from old or abandoned oil and gas facilities for decades. In 2008, three wells drilled and abandoned in the 50’s and 60’s by Texaco but the responsibility of Imperial Oil after the two companies merged, were found leaking within the town limits of Calmar, Alberta. There are a total of 26 energy wells within the town limits. One leaking well was found in a playground surrounded by homes, another was found because of bubbling gas in a puddle next to an elementary school. Four homes were demolished to allow a rig in to re-abandon and seal the wells, and the families relocated. Another family is suing because the company is refusing to pay fair market value.

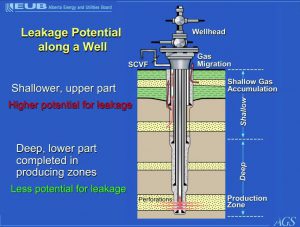

7. A Husky 1993 report states: “Gas migration has received increasing attention in recent years….industry and regulators have become more cognizant [of] the problem, in terms of the numbers of wells affected, the potential cost to address the problems and the technical difficulty of completely stopping the leakage….the expected costs to eliminate gas migration are $300,000 per site overall”. Husky reported that “roughly half the wells” in the area they studied were affected but “little consistent data was obtained with respect to the causes of the problem or what might be done about it…a technical solution which totally eliminates the problem may never be possible.” Husky asked if part of the gas migration problem is caused by “natural sources” or biogenic swamp gas using industry wellbores as conduits. The ERCB presented that the “shallower, upper part” of industry well bores (where the biogenic gas is) have “higher potential for leakage” than deep production zones. Dr. Karlis Muehlenbachs presented in November 2011 in Washington that 70% of casing gases come from intermediate layers of well bores, not the target zone, and questioned how effective casings are at preventing migrating gas from reaching the surface.

8. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) noted the problem of methane migration dramatically increased when drilling density increased. This trend has also been reported in the United States. Alberta researchers reported natural gas leakage along well bores of about 50% of oil wells in western Canada. CAPP reported that well bores were leaking gas and contaminating groundwater long before the new high pressure and densely drilled hydraulic fracturing began.

9. The University of Alberta’s Dr. Karlis Muehlenbachs developed the technique of sourcing industry-caused leaks, namely Surface Casing Vent Flow (SCVF) and Gas Migration (GM), using stable carbon isotopic analysis or isotopic fingerprinting of the gases. In 1999, the Alberta’s energy regulator, now the Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB), released Bulletin GB-99-06 recommending his technique: “Therefore, the Alberta Energy and Utilities Board (EUB) and Saskatchewan Energy and Mines (SEM) are prepared to accept the use and validity of this method on a site specific basis. Development and availability of high quality regional databases, containing interpreted analytical and geological information, are necessary prerequisites to defensible, extrapolated diagnoses for SCVF/GM problems. The need to involve qualified expertise is also necessary.”

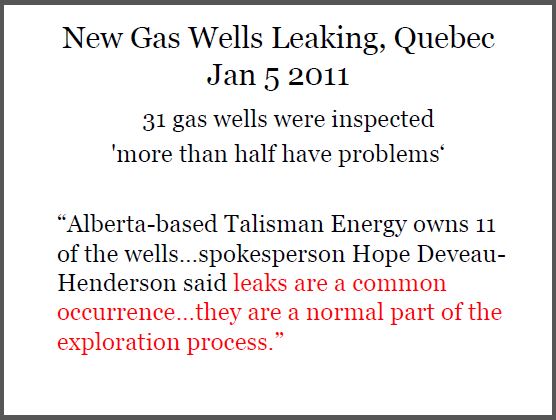

10. In Quebec, more than 50% of 31 new fractured shale wells that were inspected are leaking natural gas; the regulator ordered the leaks repaired, the companies tried but failed to stop the leaks. Isotopic analysis by Dr. Muehlenbachs indicates that groundwater in Quebec is already contaminated, “from a geological point of view, the shale was sealed 300 million years ago.” he says. “And then man intervened.” A 2008 review of investigations in a heavily drilled CBM field in Colorado concluded “There is a temporal trend of increasing methane in groundwater samples over the last seven years coincident with the increased number of gas wells installed in the study area.” In 2009, the Society of Petroleum Engineers published a peer reviewed paper that stated “in areas of high well density, well-to-well cross flow may occur in a single well leaking to surface through many nearby wellbores.” In 2009, Canada’s National Energy Board reported that only 20% of fractured gas is recoverable , “the circulating gas left behind will threaten the water Quebecers drink and could jeopardize agriculture”.

In 2011, a peer reviewed study reported that in active gas-extraction areas (one or more gas wells within 1 km), average dissolved methane concentrations in drinking water wells increased with proximity to the nearest gas well and was 19.2 mg/litre; samples in neighboring non-extraction sites (no gas wells within 1 km) averaged only 1.1 mg/litre . In contrast, dissolved methane concentrations in contaminated water wells (each with at least three gas wells within one km) under investigation at Rosebud, Alberta averaged 43.0 mg/litre after a company repeatedly fractured into the aquifers that supply those wells. Subsequent review on sampling methodology indicated that groundwater gas concentrations were being underestimated by a factor of three.

Isotopic fingerprinting of several aquifer gas samples collected for Imperial Oil in the Cold Lake area “indicate a contribution of hydrocarbons from deeper geologic strata that reflect known releases of production fluids from leaks in well casing”. In 2006 a water sampling company noted that natural gas leaks from surface casing vents in western Canada had “the potential to contaminate ground-water, kill vegetation and become a safety concern.”

A 2002 field study by Trican Well Service and Husky Energy reported that the percentage of leaking wells ranged from 12% in the Tangleflag area in eastern Alberta to as high as 80% in the Abbey gas field in southern Alberta . In 2004 the ERCB reported that the number of leaking gas wells in the Wabanum Lake area increased from none in 1990 to more than 140 in 2004.

Schumblerger Well Cementing Services reports gas migration problems at 25% in Alberta’s heavy oil fields. Although the ERCB reported that there were “3810 wells with active surface casing vent flow and 814 with gas migration problems in Alberta,” since 1999 it no longer makes this data public.

A peer reviewed paper published in 2009 by the Society of Petroleum Engineers co-authored by the ERCB states that the regulator “records well leakage at the surface as surface-casing-vent flow (SCVF) through wellbore annuli and gas migration (GM) outside the casing, as reported by industry” and maintains information on “casing failures” but that details are “not publicly available”. The paper reports that “SCVF is commonly encountered in the oil and gas industry….high buildup pressures may potentially force gas into underground water aquifers” and that soil GM occurs when deep or shallow gas migrates up outside the wellbore “through poorly cemented surface casing.” The paper concluded that the factors affecting wellbore leakage “can be generalized and applied to other basins and/or jurisdictions.”

Yes, the industry’s own researchers found that a substantial percentage of wells leak initially, an even higher percentage of wells leak eventually, and now more wells are leaking than in the past; the process is getting worse, not better.

Fractured Future

11. Nearly two decades ago Husky Oil advised that extensive gas leakage from oil and gas wells in eastern Alberta was largely due to “inadequate cementing.” A 2001 Australian study that investigated the causes of cement failure in industry wells concluded poor cement work poses a central risk to aquifers. The causes of cement failure include high cement permeability, shrinkage and carbonation, as well as formation damage.

Cement pulsation researchers reported a study that showed 15% of primary cement jobs fail, costing the oil and gas industry about half a billion dollars annually, with about one-third of the failures “attributable to gas migration or formation water flow during placement and transition of the cement to set.” The industry publication GasTIPS reported: “A chronic problem for the oil and gas industry is failure to achieve reservoir isolation as a result of poor primary cement jobs, particularly in gas wells….remedial squeeze treatment is expensive and treating pressures may breakdown the formation” and that there are areas in Alberta and Saskatchewan that have historically had gas migration problems, “on average 57% of gas wells develop gas migration after the primary cement job.”

Alberta industry data shows that “wellbore deviation is a major factor affecting overall well-bore leakage” and that in one test area, deviated wells leaked about 50% more than the area average, cement slumping and casing centralization were suggested reasons why. The data also shows a strong correlation between the percentage of wells leaking and oil price.

January 2006, the ERCB reported in their original Directive 027 that shallow fracturing harmed oilfield wells (by communication events) and information provided by industry “shows there may not always be a complete understanding of fracture propagation at shallow depths and that programs are not always subject to rigorous engineering design,” a few examples were filed.

In 2010, the British Columbia Oil and Gas Commission released a Safety Advisory because of deep fracture communication incidents, 18 in British Columbia, one in Western Alberta. The Advisory states: “A large kick was recently taken on a well being horizontally drilled for unconventional gas production in the Montney formation. The kick was caused by a fracturing operation being conducted on an adjacent horizontal well. Fracture sand was circulated from the drilling wellbore, which was 670m from the wellbore undergoing the fracturing operation….Fracture fluids introduced into producing wells results in suspended production, substantial remediation costs and post a potential safety hazard. Incidents have occurred in horizontal wells with separation distances between well bores ranging from 50m to 715m. Fracture propagation via large scale hydraulic fracturing operations has proven difficult to predict. Existing planes of weakness in target formations may result in fracture lengths that exceed initial design expectations.”

One of the Safety Advisory recommendations is that “operators cooperate through notifications and monitoring of all drilling and completion operations where fracturing takes place within 1000m of well bores existing or currently being drilled.” This protection is not recommended by either the Alberta or British Columbia regulator for shallow or deep fracture operations near farms, houses, water wells, municipal water supply towers, fire halls, non oil and gas businesses, communities, hospitals, parks, schools, etc. When concerned citizens or municipalities ask for this simple and reasonable protection, companies and regulators deflect, lie and or bully the requests away.

In 2006, the international 2nd Well Bore Integrity Network Meeting’s first key conclusion started with “There is clearly a problem with well bore integrity in existing oil and gas production wells, worldwide.”

11. Maurice Dusseault, a prominent Canadian oil patch researcher and gas migration expert, reported that leaking methane gas from thousands of resource wells posed “massive environmental problems” because the escaping methane “changes the water, and generates aquifer problems.” Dusseault explained in an Alberta report on heavy oil that, “all unplugged wells will leak eventually, and even many wells that have been properly abandoned” would also leak gas up to the surface outside of the well casing posing a hazard to groundwater and the atmosphere. In 2006, the ERCB reported that 362,265 total resource wells have been drilled in Alberta of which 116, 550 are abandoned.

Since 2001 Alberta permitted the drilling of nearly 8,000 coal bed methane wells without standardized baseline hydrogeological investigations. Many gas-bearing coal seams are directly connected to drinking water aquifers. In 2011, the ERCB reported that by “the end of 2010, there were more than 15,300 CBM wells….When CBM development began, some Albertans expressed concerns that we would experience similar impacts to those occurring in some U.S. jurisdictions. We soon learned that our geology and world-class regulations helped us avoid these problems.”

12. CAPP reported that only 17 of about 24,000 historic water well records reviewed by Alberta Environmental Protection (now Alberta Environment) for their gas migration study indicated gas present before oil and gas development. Only four out of 2,300 historic water well records within about 50 square kilometers of Rosebud, Alberta noted gas present before experimental hydraulic fracturing for CBM began in 2001 . The ERCB conducted an extensive CBM water chemistry study and reported in 2006 that about 90% of water wells in coal they tested had no detectable methane or ethane present.

Regional groundwater assessments by Hydogeological Consultants Ltd. (HCL) in conjunction with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration were completed for 45 Counties and Municipal Districts in Alberta during the initial years of shallow hydraulic fracturing. These regional assessments included identifying aquifers and quality and quantity of the water in those aquifers. They do not state that methane is naturally present in all water wells in coal in Alberta. After the media reported dangerous levels of methane in numerous water wells in Alberta after CBM developments, and the contaminated Bruce Jack water well exploded at Spirit River in 2006 seriously injuring and hospitalizing three men including two industry water well testers, Alberta regulators began telling the public that all water wells in coal are naturally contaminated with methane.

13. The development of CBM and other unconventional deposits of natural gas in Alberta and the United States requires extensive hydraulic fracturing. Hydraulic fracturing consists of injecting diesel fuel, water, foams, silica, nitrogen and undisclosed mixes of chemicals into a coal formation to force the tightly adsorbed methane to release. Some fracturing chemicals that pose a threat to human health include benzene , phenanthrenes and florenes , naphthalene , 1-methylnapthalene, 2-methylnapthalene, aromatics, ethylene glycol and methanol. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) about 40 percent of every fracturing treatment remains in the ground where it poses a threat to groundwater; CBM requires five to 10 times more fracturing than conventional natural gas wells. In 2008, Congress moved to protect drinking water in the United States from hydraulic fracturing and in 2010 the Committee on Energy and Commerce investigated numerous companies, including EnCana, regarding their hydraulic fracturing practices and all allegations of groundwater contamination. Although CBM fracturing into drinking water supplies in Alberta occurred in 2004 , perhaps earlier, regulators did not forbid the use of toxic fracturing chemicals above the base of groundwater protection until 2006.

14. EnCana, one of North America’s largest CBM drillers, publicly admitted that the same fracturing practices and gelled fluids used in the United States, which included using diesel, have been applied in Alberta. A 2005 study by the company tested recovered fracturing fluids and drilling waste mixed with water from 20 shallow gas wells on the Suffield Range in southeastern Alberta. The study, which detected metals such as chromium, arsenic, barium and mercury, and BTEX (benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene and xylenes), recommended that “Frac fluid companies should investigate the use of alternative additives that may be even more environmentally friendly (i.e. lower toxicity).” EnCana dumped and continues to dump their waste on agricultural lands in Alberta, including around Rosebud. Alberta Environment found BTEX in the Hamlet of Rosebud municipal water supply, arsenic and hexavalent chromium in a monitoring water well in the Hamlet and red flag indicators of petroleum distillates in the hamlet water and citizen water wells after heavy CBM drilling and waste dumping. The chromium in the Ernst water well increased by a factor of 45 after EnCana fractured the aquifer that supplies that well. The regulator did not test for arsenic or mercury in the contaminated citizen wells at Rosebud.

15. Lost circulation or the seepage of cement and other fluids into the ground is a constant problem with CBM and other unconventional gas drilling. EnCana experienced 10% lost circulation in one CBM field and EnCana drilling and fracturing records for CBM wells near the contaminated Campbell water well at Ponoka, Alberta indicate “severe” lost circulation events. Lost circulation poses a variety of risks to groundwater including contamination by products used to stop the seepage. Although EnCana and other companies claim that they only use fibre to seal the leaks, many of the products are toxic.

Industry, for example, often refers to Soltex (sodium asphalt sulphonate) as a “cellulose based” product, but the compound can include high amounts of antimony, arsenic, barium, chromium, lead and mercury. Oilweek Magazine lists almost a hundred products used for lost circulation including oil soluble resin polymer system, high lignin cellulosic, acid soluble blend, graphite plugging agent, and oil wet cellulose fiber. Ferro-chrome lignosulfonate (thinner and deflocculant), is a drilling mud additive listed as being used in Alberta and has been reported to negatively affect fish eggs and fry . Drilling muds and petroleum industry wastes are sometimes disposed of in pits or by land dumping (termed “spraying” or “farming” to make it more palatable to farmers and ranchers paid to take the waste). The toxics in the wastes are not disclosed to landowners or communities, and can be toxic to human health and contaminate groundwater. Groundwater flow systems can transport pollutants several kilometers.

16. A 2008 analysis of 457 chemicals used by oil and gas industry for drilling and fracturing in five western states found that 92 percent had adverse health effects and that more than one quarter was water-soluble. In a 2011 peer reviewed paper, researchers compiled a list of 944 products containing 632 chemicals used during natural gas operations and reported: “These results indicate that many chemicals used during the fracturing and drilling stages of gas operations may have long-term health effects that are not immediately expressed….The discussion highlights the difficulty of developing effective water quality monitoring programs.”

17. Since 2003, more than fifteen Alberta landowners reported contamination of their water wells after intense CBM drilling. Alberta Environment reluctantly and partially sampled some of these wells. Analysis by the Alberta Research Council (ARC) and other labs detected industrial contamination (some examples: benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene, xylenes, H2S and heavy hydrocarbons indicative of contamination by the petroleum distillates kerosene and naphthalene). Methodical studies by the University of Alberta on the gases in the water also indicated industrial contamination. Although Alberta Environment finally released a Standard for Baseline Water Well Testing for CBM in 2006, it is not standardized, only applicable to very shallow CBM wells and does not mandate the testing of red flag indicators of petroleum industry contamination. The ERCB reported that shallow and deep shales will be fractured in Alberta, and is considering chemical disclosure, but not baseline water well testing.

18. In 2009, a study published in The Journal of Hydrology concluded that CBM development has lowered and will continue to lower aquifers in the southern portion of the Powder River Basin in Montana and that the drawdown is significant and extends for miles. In 2007, the ARC reported that static water levels in Rosebud complainant water wells dropped significantly (in one case more than 3.5 metres) after a CBM producer repeatedly fractured the area’s drinking water aquifers and experimented with hundreds of secret shallow completions in the area. In 2006, Alberta Environment reported that CBM may cause “water level decline and yield reduction in water wells” and “methane gas release, gas migration into shallow aquifers, basements, explosions etc.”

19. A 2008 report by the ARC noted that Alberta Environment still does not have “a specific and documented response process” for investigating groundwater contamination and that “data gathering and evaluation decisions are made somewhat subjectively.” In addition “specific responsibilities of Alberta Environment towards the companies and water well owners are not clearly delineated and appear to vary between complaints.”

In 2006, the Texas Railroad Commission recorded 351 cases of groundwater contamination due to oil and gas activity. In 2007, New Mexico recorded 705 incidents of groundwater contamination due to oil and gas development since 1990.

In 1996, a serious and sudden gas migration incident while drilling was reported: “Dale Fox Drilling Gas Well on Bixby Hill Rd, Freedom. Natural gas escaped thru fault in shale, affected properties apprx 1 & ½ miles SW on Weaver Rd. Town of Yorkshire. Gas bubbling in Ron Lewis’s pond. Bubbling in ditch west side of Weaver Rd. 12 Families evacuated. Gas in Lewis’s basement (built on shale). Farmer’s well in barn 11708 Weaver Rd (Steve Woldszyn) vented to outside. Gas coming up throu ground in Lewis’s yard.” Four Plaintiffs took the case to the Supreme Court of the State of New York, and won their case. In the court documents, the defendant Dale Fox admitted what happened: “On November 19th, we drilled into the reef. As we did, at approximately 2600 feet of depth, the reef began to produce gas and came up the drilling pipe and sprayed out the discharge pipe. The direction of the wind at the time caused the mist and gas to be blown back on us and the rig. Because of the fire hazard, we immediately cased drilling operations and engaged the BOP. We began pumping brine into the well, along with a defoamer, but the pressure [from] the formation spit the brine back up as foam. Foam lacks weight and density to kill a well, so we could not pump it back in. We used all three hundred gallons of brine by 8:00PM, and shut down operations. We ordered heavier fluid to pump into the well (called Gel or Mud). Unfortunately that could not be delivered until the next day….On November 20, Mud was delivered, mixed and pumped into the well. We successfully killed the well. In all my years of drilling and oil and gas work, I have never encountered or heard about pressure like that from a formation.”

A comprehensive investigation in Kansas demonstrated that leaking industry gas had migrated more than six miles. The migrating gas caused explosions in 2001 in Hutchinson that destroyed two businesses and damaged many others. Two people died from injuries in a subsequent explosion three miles away the next day caused by the migrating gas.

20. Alberta’s Department of Energy defines fracturing as: “the opening up of fractures in the formation to make gas flow more freely.” Fracturing can also result in the migration of methane “toward the land surface through natural fractures in the rock and through old drill holes that were poorly plugged when abandoned. Wells that once were good water wells now become water and gas wells. In some cases good water wells become better gas wells than water wells.”

21. In 2003, the ARC reported that natural methane release in Alberta is rare because reservoirs are “tight” and that nitrogen used in CBM recovery “increases diffusion rate of hydrocarbon gases from coal matrix into natural fractures” . Hydraulic fracturing has been associated with gas migration into groundwater as well as groundwater drawdown or contamination throughout the continent. A 1994 Colorado study of 203 water wells in a area of high CBM density by the United States Geological Survey found that “manmade migration pathways probably” accounted for the contamination of shallow water wells by methane. A 2006 USGS study discovered extensive methane contamination of local drinking wells in areas of intense coal mining.

22. Alberta Environment , CAPP and the Canadian Society for Unconventional Gas warned that natural gas in water wells can be dangerous to property and people. Water wells in Alberta contaminated with migrant gases have blown up; in one case three men were seriously injured and hospitalized. Homes in the U.S. have exploded from migrant resource well gases . Leaking gas wells have created dangerous concentrations of dissolved methane in household water wells as high as 92 mg/litre in Tioga County in north central Pennsylvania.

A 2008 regulator report summarized the contamination of Bainbridge, Ohio water wells with methane leaking from a recently fractured energy well with faulty casing. The fugitive methane caused an explosion seriously damaging one home and required the evacuation of 19 others. The company immediately assumed responsibility, provided temporary housing and “disconnected 26 water wells, purged gas from domestic plumbing/heater systems, installed vents on six water wells, plugged abandoned in-house water wells, plumbed 26 houses to temporary water supplies, provided 49 in-house methane monitoring systems for homeowner installation, and began to provide bottled drinking water to 48 residences upon request.”

The highest concentration of dissolved methane found in 79 ground water samples at Bainbridge, Ohio was 1.04 mg/litre. The highest found in Rosebud, Alberta after the community fresh water supply was hydraulically fractured by a CBM developer was 66.3 mg/litre. CAPP, Canada’s oil and gas lobby group, warned in their 1996 gas migration report that if there is more than 1 mg/litre of dissolved methane in water, “there may be a risk of an explosion, if the water supplies pass through poorly ventilated air spaces” and reported that dramatically increased levels of methane were found in groundwater near leaking hydrocarbon wells, with the highest at 19.1 mg/litre.

Water samples from the Amos/Walker well in Colorado, where EnCana received a notice of violation and a large fine from the regulator for impacting the water, showed methane concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 13 mg/litre. The Amos case settled with a confidentiality agreement and payout. (EnCana had received notice of violation and a record fine from the same regulator in Colorado for contaminating water and a creek with methane and benzene the year previous. )

In 2010, the EPA issued an emergency order to Range Resources to take immediate action to protect landowners with explosive levels of methane in their water, “homeowners who lived near drilling operations of Range Resources in Parker County, Texas, reported problems with their tap water, complaining that it was bubbling and even flammable.” Heavier hydrocarbons were also found in the water. Levels of dissolved methane in the 25 affected water wells, including two municipal wells, ranged from 0.62 to under 28 mg/litre. “Range experts say their analysis found the methane in the water wells is actually coming from the more shallow formation”; the EPA said that Range has not supplied all the technical information required in its order.”

A 2009 regulator report summarized 64 gas migration cases in 22 counties in Pennsylvania dating from the 1990’s to 2009 caused by the oil and gas industry; five cases were caused by hydraulic fracturing that contaminated numerous wells and two springs used as domestic water supply. The 64 cases resulted in 11 explosions, five fatalities, three injuries, a road closure, and numerous evacuations with residents in one community displaced for two months. The fugitive methane in the Dimock case migrated nine square miles affecting 14 water supplies. At the end of 2011, the EPA reopened the contamination investigation at Dimock because litigants released sealed water data collected by Cabot Oil and Gas that indicate fracturing might be responsible.

The DEP fined Chesapeake Energy $900,000 for methane migration “up faulting wells” in Bradford County, contaminating 16 families’ drinking water in 2010. The DEP found methane concentrations ranging from 2.16 to 55.8 mg/litre. “DEP Secretary Michael Krancer said the contamination fine is the largest single penalty the agency has ever levied against a driller….As part of the consent order issued by the department, Chesapeake will have to remediate the contaminated water supplies, take steps to fix the faulty gas wells and report any water supply complaints to the DEP.”

In 2012, the Pennsylvania state regulator released a notice of violation to Cabot Oil and Gas for contaminating three private water wells in Lenox Twp, Susquehanna County, with methane that seeped from a flawed natural gas well; the notice of violation states that the dissolved methane in one water supply jumped from 0.29 mg/litre in a 2010 pre-drilling sample to 49.2 mg/litre and 57.6 mg/litre after drilling. “It bubbled up in a private pond, a beaver pond and the Susquehanna River from as many as six sets of faulty wells in five towns.” Cabot installed methane detection alarms in three homes and vented the three affected water wells to keep the methane from accumulating and creating an explosion risk.

In a 2011 draft report, the EPA connected natural gas and toxic chemicals found in drinking water wells at Pavillion, Wyoming to hydraulic fracturing and waste pits by EnCana. The EPA reported: “Hydraulic fracturing in gas production wells occurred as shallow as 372 meters below ground surface” In comparison, at Rosebud, Alberta, EnCana fractured as shallow as 121.5 metres below ground surface , with perforations as shallow as 100.5 metres . About 62 gas wells were fractured less than 200 m below ground surface within about six miles of Rosebud.

The way I read the EPA report, the surface casings were too short and that the cementing was inadequate and then they fracked at very shallow depths. It’s almost negligence

Dr. Karlis Muehlenbachs

The Canadian oil and gas industry advertised in 2010 that “in all cases groundwater and the hydraulically fractured zone are isolated to prevent potential cross-flow of fluids between the natural gas-producing intervals and groundwater aquifers.” EnCana’s well data shows this not to be the case.

Methane concentrations in Rosebud water wells are much higher than the EPA found in Pavillion, Wyoming or Parker County, Texas.

In 2006, the Alberta government promised in the Legislature that all affected families would receive safe alternate water “now and into the future” and knew that isotopic fingerprinting of gases from Rosebud water indicated match to EnCana’s gas wells in the community. The government refused to disclose this damning data to complainants claiming “confidentiality”, but immediately disclosed the data to EnCana (this and the damning data was found out years later via Freedom of Information Requests). The government then proceeded for over a year to refuse complainants sampling and safety protocols and a comprehensive investigation while allowing EnCana to drill and fracture numerous more shallow wells and commingle existing and new wells in the area where the company fractured the community’s fresh water aquifers. In 2007, within a month of promising a comprehensive investigation the government reneged and a year later broke their promise of safe water. Citizens breath, bathe in and ingest the fumes, and live with dangerous, contaminated water or haul their own.

You don’t care if it comes from fracking or a bad cement job, you suffer the consequences all the same, and lose your well water

Dr. Karlis Muehlenbachs

Some of the contaminants found in sampling by the EPA at Pavillion where found in sampling by Alberta Environment in groundwater at Rosebud, Alberta and dismissed, ignored or reported incorrectly by the ARC. These include: diesel range organics, benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylenes, and tert-butyl alcohol – a known breakdown product of methyl tert-butyl ether (a fuel additive) that is not expected to occur naturally in ground water. Freedom of Information request responses show that companies have not disclosed to Alberta regulators or affected families the chemicals experimented with and injected in communities with water contamination even though the ERCB reports that it “requires that the type and volume of all additives used in fracture fluids be recorded in the daily record of drilling operations for any well.”

The “World Class” regulators do not report or map cases of groundwater contamination caused by the petroleum industry in Alberta. They continue to publicly claim it hasn’t happened.

It’s stupid! Don’t do it.

Dr. Tony Ingraffea

[Note added Feburary 4, 2020:

I’ve noticed since I began trying to warn people about frac’ing in 2003, that shortly after I publicly present on regulator/industry research, the previously publicly available documents vanish off regulator/corporate websites. I upload those that disappear when I am able because they are important to the public’s safety, but as with trying to keep on top of Natural Resources Canada scrubbing frac quakes from Earthquakes Canada’s website, it’s time consuming to manage.

Many of the references below vanished after I sent my submission to the NY DEC and Governor Cuomo. I uploaded those that I had saved and updated the links in my 2013 version of this paper that I shared with the public: Brief review of threats to Canada’s groundwater from the oil and gas industry’s methane migration and hydraulic fracturing]

Diagram

Bachu, S. and T. Watson. 2007. Factors Affecting or Indicating Potential Wellbore Leakage Presentation to the 3rd IEA-GHG Wellbore Workshop, March 12-13, 2007. Slide 25. Alberta Energy and Utilities Board with T. L. Watson and Associates Inc.

References

Alberta Environment. March 2006. Analytical Report for Rosebud Hamlet. Data collection by Alberta Environment, analysis by ALS Laboratory Group and the Alberta Research Council [name changed to Alberta Innovates Technologies Futures, shortly after the council dismissed the contamination cases, suggesting nature to blame but unable to explain where the methane came from]

Alberta Environment. April 2006. Standard for Baseline Water-Well Testing for Coalbed Methane/Natural Gas in Coal Operations.

Alberta Environment. January 16, 2008. Letters to Complainants from Mr. David McKenna, Alberta Environment, Groundwater Policy Branch. Groundwater Contamination Investigation No. 7894.

Alberta Department of Energy. Coalbed Methane FAQs.

Alberta Hansard, May 17, 2006: Private water well explosion at Spirit River under Coalbed Methane Drilling.

Albrecht, Tammy. August 2008. Using sequential hydrochemical analysis to characterize water quality variability at Mamm Creek Gas Field Area, Southeast Piceance Basin, Colorado. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Trustees of the Colorado School of Mines in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Hydrology).

Arkadaskiy, S. K. Muehlenbachs, C. Mendoza, and B. Szatkowski. 2005. Anaerobic oxidation of natural gas in soil – The geochemicals evidence? Goldschmidt Conference Abstracts 2005. Life in Extreme Environments.

Bachu, S. and M. A. Celia. November, 2005. Evaluation of the Fate of CO2 Injected into Deep Saline Aquifers in the Wabamum Lake Area, Alberta Basin, Canada. Proposed Test Case. Princeton Workshop on Geological Storage of CO2, November 1-3, 2005.

Bachu, S. and T. Watson. 2007. Factors Affecting or Indicating Potential Wellbore Leakage Presentation to the 3rd IEA-GHG Wellbore Workshop, March 12-13, 2007.

Blyth, Alexander. January, 2008. An Independent Review of Coalbed Methane Related Water Well Complaints filed with Alberta Environment. Alberta Research Council Inc.

Blyth, A. December 31, 2007. Ernst Water Well Complaint Review Alberta Research Council Inc. Prepared for Alberta Environment.

lyth, A. December 31, 2007. Signer Water Well Complaint Review. Alberta Research Council Inc. Prepared for Alberta Environment.

Blyth, A. December 20, 2007. Lauridsen Water Well Complaint Review. Alberta Research Council Inc. Prepared for Alberta Environment.

Bodycote Testing Group. 2006. Trials and Tribulations of a New Regulation: Coal Bed Methane Water Well Testing. Presentation by D. Lintott, C. Swyngedouw and E. Schneider of Norwest Labs – Bodycote for Remtech 2006 Proceedings.

Bredenhoeft, J. 2003. Letter to Environmental Protection Agency Re: EPA draft study report—Evaluation of Impacts to Underground Sources of DrinkingWater by Hydraulic Fracturing of Coalbed Methane Reservoirs: Subject: Federal Register August 28, 2002, Volume 67, Number 10, Pages 55249-55251 (water Docket Id no. w-01-09-11). The Hydrodynamics Group: studies in mass and energy transport in the earth.

British Columbia Oil and Gas Commission Safety Advisory 2010-03. May 20, 2010. Communication during fracturing stimulation

Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. 1995. Migration of Methane into Groundwater from Leaking Production Wells Near Lloydminster; March 1995. CAPP Pub. #1995-0001.

Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. 1996. Migration of Methane into Groundwater from Leaking Production Wells Near Lloydminster; Report for Phase 2 (1995). CAPP Pub. #1996-0003.

Canadian Natural Gas, 2010 Full Potential: Unconventional Gas Development in Canada. Canadian Natural Gas is a made-in-Canada advocacy project sponsored by the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers and other industry lobby groups.

Canadian Society for Unconventional Gas http://www.csug.ca/facts.html [renamed in 2011 to Canadian Society for Unconventional Resources] http://www.csur.com/ Williamson, Ken. Natural Gas from Water Wells can be Dangerous Agriculture Water Specialist, Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development.

CBC News. Leaks found in shale gas wells: Que. Report; 31 were inspected and ‘more than half have problems,’ says environmental expert. January 5, 2011

CBC News. November 29, 2011 FRACTURED FUTURE Does the natural gas industry need a new messenger?A series of special op-eds about the shale gas industry

Chafin, Daniel, T. 1994. Source and Migration Pathways of Natural Gas in Near-Surface Ground Water Beneath the Animas River Valley, Colorado and New Mexico USGS Water Resources Investigations Report 94-4006.

Colborn, T., C. Kwiatkowski, K. Schultz, and M. Bachran Natural Gas Operations from a Public Health Perspective Accepted for publication in the International Journal of Human and Ecological Risk Assessment, September 4, 2010. Expected publication September-October 2011

Coleman, D. 2004. Source Identification of Stray Gases by Geochemical Fingerprinting. Isotech Laboratories, Inc. champaign, Illinois, USA. Solution Mining Research Institute; Spring 2004 Technical Meeting Wichita, Kansas, USA, 18-21 April 2004.

Colorado Oil and Gas Commission. June 10, 2005. Alleged Violations of the rules and regulations of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) by EnCana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. Cause No. 1V, DOCKET NO. 0507-OV-07 before the Oil and Gas Conservation Commission of the State of Colorado

Colorado Oil and Gas Commission. September 16, 2004. Alleged Violations of the rules and regulations of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) by EnCana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. Cause No. 1V, Order No. 1V-276 before the Oil and Gas Conservation Commission of the State of Colorado.

Congress of the United States Committee on Energy and Commerce letter dated July 19, 2010 to Mr. Randy Eresman, President and Chief Operating Officer of EnCana.

Côté, Charles. December 29, 2011. Eau contaminée: le ministre Arcand prend la situation «très au sérieux» Un-authorized translation in La Presse.

Crowe, A.S., K.A. Schaefer, A. Kohut, S.G. Shikaze, C.J. Ptacek. 2003. Groundwater Quality Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Winnipeg, Manitoba. Linking Water Science to Policy Workshop Series. Report No.2, 52 pages.

Debruijn, Gunnar. 2008. Expert Viewpoint-Well Cementing. Schlumberger Limited.

de la Cruz, N. 2006. Coalbed Methane/Natural Gas in Coal and Groundwater Alberta Environment Conference, May 2006. Slide 12.

Dougherty, K. Fracking will cause ‘irreversible harm’ Shale-gas extraction a huge risk originally published in The Montreal Gazette, March 7, 2011.

Dusseault, M. B. Summer, 2002. Why Old Wells Leak. Cement-Casing Rock Interaction – University of Waterloo/Porous Media Research Institute. In Eye on Environment.

Dusseault, M. B. 2003. Some Recommendations Relating to Alberta Heavy Oil. Report prepared for the Alberta Department of Energy.

Dusterhoff, Dale, G. Wilson, and K. Newman. 2002. Field Study on the use of Cement Pulsation to Control Gas Migration Paper presented to the Society of Petroleum Engineers Inc.

EnCana. 2005. Recycling Frac Fluid Pilot Investigation into Water Based Frac Fluid Use in Drilling Fluids Associated with Shallow Gas Wells on the Suffield Block. PTAC 2005 Water Efficiency and Innovation Forum, June 23, Calgary. Previously available at: http://www.ptac.org/env/dl/envf0502p07.pdf

EnCana. 2001. 02/06-04-27-22-W4M CBM completion data on file at Alberta’s Groundwater Centre; most shallow at 100.5m

EnCana. 2001. 02/06-04-27-22-W4M CBM drilling and fracturing data on file at the ERCB

EnCana. 2003. 00/05-14-27-22-W4M CBM completion data on file at Alberta’s Groundwater Centre, most shallow at 121.5m.

EnCana. 2004. 00/05-14-27-22-W4M CBM drilling and fracturing data on file at the ERCB

EnCana. 2005. 00/02-23-43-28-W4M CBM drilling and fracturing data on file at the ERCB severe lost circulation

EnCana. 2005. 02/02-23-43-28-W4M CBM drilling and fracturing data on file at the ERCB severe lost circulation

EnCana. Advertising brochure on the company website www.encana.com September 19, 2011. Quick Info: Hydraulic Fracturing.

Environmental Protection Agency. December, 1987. EPA Report to Congress: Management of Wastes from the Exploration, Development, and Production of Crude Oil, Natural Gas, and Geothermal Energy Volume 1 of 3 Oil and Gas, EPA/530-SW-88-003, December 1987.

Environmental Protection Agency. June, 2004. Public Comment and Response Summary for the Study of the Potential Impacts of Hydraulic Fracturing of Coalbed Methane Wells On Underground Sources of Drinking Water.

Environmental Protection Agency. January 13, 2011. Range Resources Imminent and Substantial Endangerment Order, Parker County, TX Administrative Record Against Range Resources Corporation and Range Production Company

Environmental Protection Agency. December 2011. Draft Investigation of Groundwater Contamination near Pavillion, Wyoming. EPA 600/R-00/000. Office of Research and Development.

ERCB (EUB) Statistical Series 57, 98/99. Field Surveillance April 1998/March 1999. Provincial Summaries.

ERCB (EUB). April 6, 1999. General Bulletin GB 99-06. Application of stable carbon isotope ratio measurements to the investigations of gas migration and surface casing vent flow sour detection.

ERCB (EUB) A listing of some shallow fracture communication events in Alberta Date unknown, but prior to 2006.

ERCB (EUB) Directive 027. January 31, 2006. Shallow Fracturing Operations-Interim Controls, Restricted Operations, and Technical Review. [Original Directive no longer available on the regulator’s website after I went public with the damning quotes in it. It was replaced with a version that did not include the quotes in this brief. The original was uploaded to this website for the public interest.]

ERCB (EUB) Decision 2006-102. EnCana Corporation Applications for Licences for 15 Wells A Pipeline and a Compressor Addition Wimborne and Twining Fields.

ERCB. January 28, 2011. Unconventional Gas Regulatory Framework—Jurisdictional Review by the Alberta Energy and Utilities Board Report 2011-A.

ERCB. October 11, 2011. Alberta’s Unconventional Oil & Natural Gas, Answering Your Questions About Our Energy Resources Package

ERCB. October 11, 2011. Alberta’s Unconventional Oil & Natural Gas, Answering Your Questions About Our Energy Resources Presentation

Ernst v. EnCana, the Alberta Energy Resources Conservation Board and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Alberta. Amended on April 21, 2011. Court File No. 0702-00120.

Fakete, J. and R. Penty. Environment Canada to study hydraulic fracturing PostMedia News and Calgary Herald, September 21, 2011

Gunter, W. January, 2003. Climate change solutions may be found in coalbed methane recovery. Climate Change Central Newsletter 5. The Canadian Government removed this from the Internet; previously available at http://www.climatechangecentral.com/info_centre/C3Views/default.asp

Hanel, Joe. December, 2005. COGCC seeks aid in dealing with wells. State Agency to ask Legislature for $800K in emergency funding. The Durango Herald.

Hawes, C. January 20, 2011. More methane found in Parker County water WFAA

Hutchinson Response Project, March 2001

Hydrogeological Consultants Ltd. January, 2005. EnCana Corporation. Redland Area. NE10-027-22-W4M. Sean Kenny Site Investigation. File No.: 04:510.

HR 7231 IH, 110th Congress 2nd Session. In the House of Representatives, September 29, 2008

Ibrahim, Mariam. July 7, 2010. Calmar residents know the drill as company works to cap abandoned well The Edmonton Journal. Previously available at http://www.edmontonjournal.com/calmar+residents+know+drill+company+works+abandoned+well/5067796/story.html

IEA Greenhouse Gas R & D Programme (IEA GHG) 2nd Wellbore Integrity Workshop, 2006/12, September, 2006.

Ingraffea, T. December, 2011 in New Brunswick. On shale gas well placement in Penobsquis

Kusnetz, N. December 28, 2011. Oh, Canada’s Become a Home for Record Fracking Propublica

Legal Environmental Assistance Foundation, Inc. (LEAF) and Ruben and Cynthia McMillan petition to the EPA regarding water well contamination in Alabama from CBM, 1995

Legere, Laura. May 18, 2011. DEP fines Chesapeake $1.1 million for fire, contamination incidents

Legere, Laura. December 31, 2011. EPA: Dimock water supplies ‘merit further investigation’ In The Times Tribute.

Legere, L. January 9, 2012. DEP: Cabot drilling caused methane in Lenox water wells The Times Tribune

Lemay, T.G., and Konhauser, K.O. September, 2006. Water Chemistry of Coalbed Methane Reservoirs. ERCB. EUB/AGS Special Report 081.

Mavroudis, Damien. 2001. Downhole Environmental Risks Associated with Drilling and Well Completion Practices in the Cooper/Eromanga Basins Department of Primary Resources and Industries South Australia. Report Book 2001-00009.

Maxxam Analytical Labs. 2006. Environmental Services Solutions. Coalbed Methane Operations, Baseline Water-Well Testing Issue No. sol-050e.

Myers, T. 2009. Groundwater management and coal bed methane development in the Powder River Basin of Montana. J. Hydrology. Vol. 368, Issues 1-4, 30 April 2009. pp 178-193. ISSN 0022-1694

Journal Homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhydrol

Muehlenbachs, K. November 14, 2011. Identifying the Sources of Fugitive Methane Associated with Shale Gas Development. Presentation in Washington, USA: Resources for the Future. Managing the Risks of Shale Gas: Identifying a Pathway toward Responsible Development

National Energy Board, November 2009 A Primer for Understanding Canadian Shale Gas – Energy Briefing Note

Natural Resources Canada. January, 2006. Results to the Information Request by Ken Ruben to Natural Resources Canada under the Access to Information Act.

Newman, K., A. Wojtanowicz, and B.C. Gahan. 2001. Cement pulsation improves gas well cementing –Statistical Data Included. World Oil.

New Mexico Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department. Generalized Record of Ground Water Impact Sites

Nikiforuk, A. December 19, 2011. Fracking Contamination “Will Get Worse”: Alberta Expert The Tyee

Ohio Department of Natural Resources. September 1, 2008. Report on the Investigation of the Natural Gas Invasion of Aquifers in Bainbridge Township of Geauga County, Ohio.

Oilfield Review. Winter 2003/2004. A Safety Net for Controlling Lost Circulation.

Oilweek Magazine, Canada’s Oil and Gas Authority. 2006 Guide to Drilling Fluids. March, 2006.

Oilweek Magazine, Canada’s Oil and Gas Authority. 2008 Guide to Drilling Fluids. March, 2008.

Osborn, S.G, A. Vengosh, N. R. Warner, and R. B. Jackson Methane contamination of drinking water accompanying gas-well drilling and hydraulic fracturing In Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences. Published online before print May 9, 2011, doi:10.1073/pnas.1100682108PNAS May 17, 2011 vol. 108no. 20 8172-8176. Approved April 14, 2011 (received for review January 13, 2011)

Pennsylvania Geological Survey. Other Geological Hazards. Methane Gas.

Petroleum Services Association of Canada. Mud list. 2005. Drilling Product Listing for Potential Toxicity Information. As usual, after I went public with it, indusry’s toxic chemical list was removed from public access. I uploaded it here: https://ernstversusencana.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/PSAC-mudlist-chemicals-HISTORICAL.pdf

Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. Bureau of Oil and Gas Management. October 2009. Stray Natural Gas Migration Associated with Oil and Gas Wells. Draft Report – Tab 10/28/09

Pennsylvania Dept. of Environmental Protection Press Release April 4, 2010 DEP Takes Aggressive Action Against Cabot Oil & Gas Corp to Enforce Environmental Laws Protect Public in Susquehanna County; Suspends Review of Cabot’s New Drilling Permit Applications Orders Company to Plug Wells Install Residential Water Systems Pay $240,000 in Fines

Pennsylvania Dept. of Environmental Protection Notice of Violation, Gas Migration Investigation, Lennox Twp. Susquehanna County. September 19, 2011.

PRNewswire. September 17, 2011. DEP Monitors Stray Gas Remediation in Bradford County; Requires Chesapeake to Eliminate Gas Migration SOURCE Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection

Lustgarten, Abrahm. July 31, 2009 Water Problems From Drilling Are More Frequent Than PA Officials Said. In Propublica.

Rosenberg International Forum on Water Policy. February, 2007. Report of the Rosenberg International Forum on Water Policy to the Ministry of Environment, Province of Alberta. University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources

Ryan, C. December, 2008. Alberta Environment Standard for Baseline Water Well Testing for CBM Operations, Science Review Panel Final Report prepared for Alberta Environment by Dr. Cathy Ryan, University of Calgary. Panel: A. Blyth, B. Mayer, C. Mendoza, K. Muehlenbachs.

Schmitz, Ron, P. Carlson, M. D. Watson, and B. P. Erno. 1993. Husky Oil’s Gas Migration Research Effort – an Update.

Standing Committee on Energy, the Environment and Natural Resources. November, 2005. Water in the West: Under Pressure Fourth Interim Report.

Stein, D., T.J. Griffin Jr., and D. Dusterhoft. 2003. Cement Pulsation Reduces Remedial Cementing Costs. In GasTIPS Winter 2003.

Sumi, Lisa. 2005. Our Drinking Water at Risk. What EPA and the Oil and Gas Industry Don’t’ Want Us to Know About Hydraulic Fracturing. Oil and Gas Accountability Project (a project of Earthworks).

Szatkowski, B., Whittaker, S., Johnston, B., Sikstrom, C., and K. Muehlenbachs, 2001. Identifying the source of dissolved hydrocarbons in aquifers using stable carbon isotopes. G-Chem Environmental Ltd., Imperial Oil Resources Ltd., and the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta.

Texas Groundwater Protection Committee. July, 2007. Joint Groundwater Monitoring and Contamination Report – 2006. SFR-056/06. Published and distributed by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

The Endocrine Disruption Exchange. 2008. Analysis of Chemicals Used in Oil & Natural Gas Develoment in Five Western States

Thyne, Geoffery. 2008. Review of Phase II Hydrogeological Study Prepared for Garfield County.

Thyne, Geoffery. 2008. Summary of PI and PII Hydrogeological Characterization Studies – Mann Creek Area, Garfield County, Colorado.

Toxics Targeting. September, 2009. Bixby Hill Rd FOIP and Court Documents.

Urbina, I. The New York Times, August 3, 2011. DRILLING DOWN, One Tainted Water Well, and Concern There May Be More

US Environmental Protection Agency. 2004. Evaluation of Impacts to Underground Sources of Drinking Water by Hydraulic Fracturing of Underground Coalbed Methane Reservoirs

US Geological Survey. January, 2006. Methane in West Virginia Ground Water. Fact Sheet 2006-3011.

U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2007-5085. Natural Gases in Ground Water near Tioga Junction, Tioga County, North-Central Pennsylvania-Occurrence and Use of Isotopes to Determine Origins, 2005.

Watson, T.L. and Bachu, S. 2009. Evaluation of the Potential for Gas and CO2 Leakage Along Wellbores. SPE Drill & Compl 24 (1): 115-126. SPE-106817-PA.

Weyer, Udo. February, 2006. Hydrogeology of shallow and deep seated groundwater flow systems. Basic principals of regional groundwater flow. WDA Consultants Inc., Calgary, Alberta

Williams, B. May 4, 2011. Press Release Calmar Homeowners Suing Town of Calmar and Aztec Home Sales Inc over Leaking Wells

Wills, J. 2000. A Survey of Offshoe Oilfield Drilling Wasters and Disposal Techniques to Reduce the Ecological Impact of Sea Dumping. M.Inst.Pet., for Ekologicheskaya Vahkta Sakhalina (Sakhalin Environment Watch.

Wright, K. 1993. Fouled water leads to court in High Country News, April 19, 1993

Zhang, Y., Person, M.A., Merino E., and M. Szpakiewcz. May, 2003. Evaluation of hydrologic and biogeochemical controls on soluble benzene migration within the Uinta Basin using computer models and field sampling. AAPG Annual Convention. Salt Lake City, Utah.