“To let this go on for 10 or 15 years and these people still have no water except for a few bottles delivered once a week is just not right.”

![]() In 2006, in the Legislature, Premier of Alberta Ralph Klein promised frac-harmed families permanent safe alternate water but some, eg the Campbells and Zimmermans, never received any and those at Rosebud had their delivered water cut off in 2008 – I expect ordered so by Encana/Ovintiv because 1) the company is a nasty lying, law-violating thug and 2) the deliveries made Ovintiv look too guilty.

In 2006, in the Legislature, Premier of Alberta Ralph Klein promised frac-harmed families permanent safe alternate water but some, eg the Campbells and Zimmermans, never received any and those at Rosebud had their delivered water cut off in 2008 – I expect ordered so by Encana/Ovintiv because 1) the company is a nasty lying, law-violating thug and 2) the deliveries made Ovintiv look too guilty.![]()

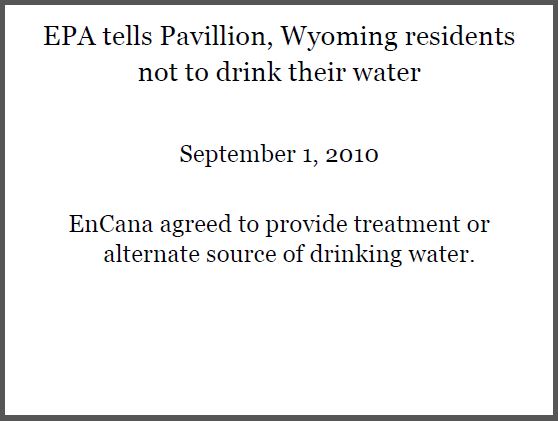

Thirty years after faulty gas wells and unlined holding ponds began contaminating groundwater, residents of Pavillion, Wyoming, still can’t drink the water by WORC, Feb 24, 2020

Sue Spencer, a hydrogeologist based in Laramie, Wyo, looks down from a sandy bluff on a two-football-field-sized swath of cleared land that designates a capped natural gas well. Two men in unmarked blue coveralls and white hard-hats stand near the edge of the site. She has no idea whether this is one of the wells that’s been contaminating the East Pavillion, Wyo. water supply, or if it’s just a well that’s been under-performing. She has no way of knowing whether simply capping the well will stop methane from leaking into the groundwater aquifer, or not.

“The people that were there sampling wouldn’t even speak to us,” Spencer said. “There’s this veil of secrecy about everything they do.”

Secrecy comes standard in the oil and gas industry. It’s enabled by state and federal policies that allow companies to hide details around hydraulic fracturing. For the residents of Pavillion, the culture of concealment around fracking makes a bad situation much worse.

“Back in 2013, Jeff Locker (a Pavillion-area farmer) showed up at our office in Laramie with three giant boxes full of documents and water quality data reports, and he wanted us to help him figure out what was going on with his well, “ Spencer said. “He’d been having problems with his well since 1992 [but] nobody was listening to him.”

Locker had his water tested in the late 1980’s when he financed his ranch. The tests indicated he had high-quality water. Four years later, his water quality degraded by a factor of 10.

The degradation of water quality falls in line with a surge in gas development in the Pavillion gas field throughout the 1990’s. Then, in the 2000’s, the density of wells went from one well per 160 acres to four. Currently, the Pavillion gas field has 169 wells.

Those wells are drilled into the Wind River Formation, a complicated sequence of sandstones and channel deposits that are layered on top of each other. The formation is about 3,500 feet thick. Without an impermeable layer to stop gas migration between the gas production zone and the drinking water aquifers, gas wells need to be constructed in a way to protect shallow groundwater wells. Well casings must be filled with concrete down below the bottom of the deepest possible water supply. Any gaps between the casing and drill bore allows gas to move freely up the open casing and out into the water-bearing layers, contaminating not only those layers, but all of the layers above as it makes its way to the surface.

According to a study done by the Wyoming Oil and Gas Commission on gas wells in the Pavillion area, 52% of the 169 wells have incomplete casings. Any number of those wells may be leaking methane into groundwater aquifers like the one the Locker family uses for drinking water. And without more complete scientific study, there’s no way to tell how much contamination is happening.

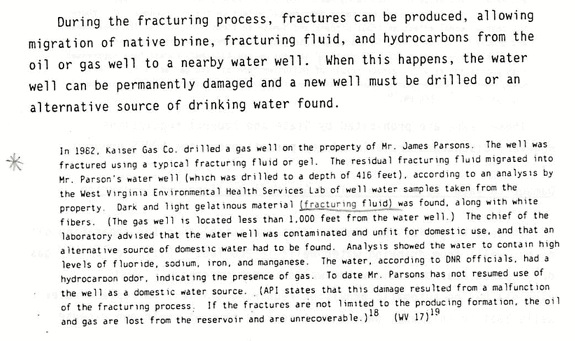

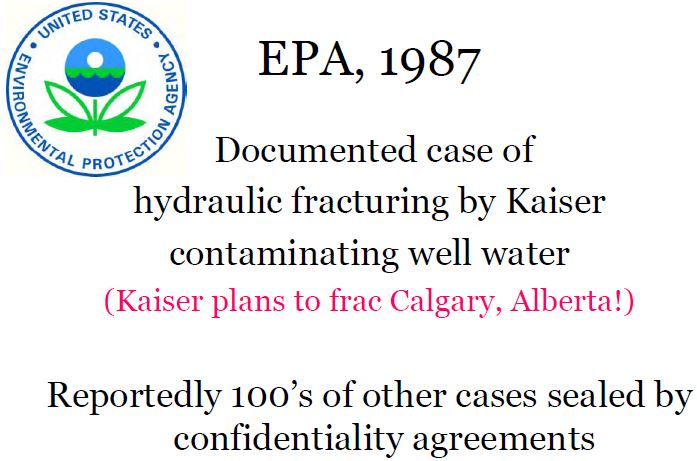

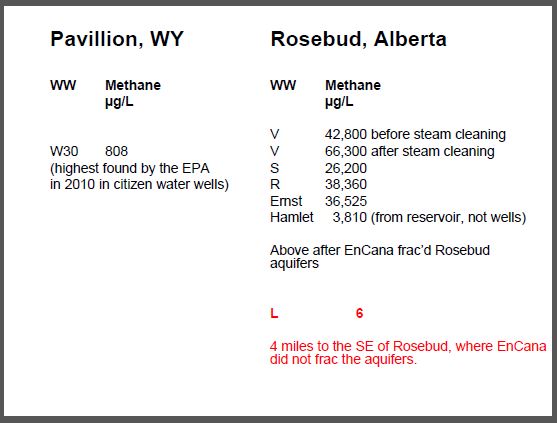

A complicating factor came in 2011 when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released a draft report that found benzene and other chemicals used in the fracking process in a 700-foot-deep freshwater aquifer far above gas-production depth. The draft report, which was never released as a final version, was the first documented evidence of fracking-related water contamination. ![]() No, there were others before that including, but not limited to: by Encana/Ovintiv’s own records in 2005 in Rosebud, Alberta followed by regulator testing of contaminated water wells and monitoring wells drilled there in 2007 (some of the chemicals found were benzene, toluene, Tert-butyl alcohol, hexavalent chromium, dangerous concentrations of methane, some ethane, and more), isotopic fingerprinting of the gases in contaminated water at Rosebud, Ponoka and Westaskiwin by Tilley and Muehlenbachs, published and presented in Cambridge UK in 2011 (even the oil and gas industry’s biggest lobby group in Canada, CAPP, and company CEOs in testimony to Parliamentary Committee admit frac’ing contaminated Rosebud’s water); in Terry Township, Bradford Co, PA in 2009; in numerous counties in PA in 2011; in West Virginia in 1987 and many other cases detailed in Andrew Nikiforuk’s Slick Water.

No, there were others before that including, but not limited to: by Encana/Ovintiv’s own records in 2005 in Rosebud, Alberta followed by regulator testing of contaminated water wells and monitoring wells drilled there in 2007 (some of the chemicals found were benzene, toluene, Tert-butyl alcohol, hexavalent chromium, dangerous concentrations of methane, some ethane, and more), isotopic fingerprinting of the gases in contaminated water at Rosebud, Ponoka and Westaskiwin by Tilley and Muehlenbachs, published and presented in Cambridge UK in 2011 (even the oil and gas industry’s biggest lobby group in Canada, CAPP, and company CEOs in testimony to Parliamentary Committee admit frac’ing contaminated Rosebud’s water); in Terry Township, Bradford Co, PA in 2009; in numerous counties in PA in 2011; in West Virginia in 1987 and many other cases detailed in Andrew Nikiforuk’s Slick Water.![]()

“The oil industry went nuts,” Spencer said. “It was right as the gas boom was starting, and [the oil lobby] was just like, ‘you can’t say that groundwater was impacted by the fracking industry.’”

Amid the backlash, the EPA caved to pressure from Encana and the state of Wyoming, allowing the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) to take over the investigation. Under DEQ, the contamination investigation was reduced to a palatability study. No new monitoring wells have been drilled, and the state of Wyoming is pushing EPA to plug their two monitoring wells. Without more monitoring, the complicated hydrogeology of the Wind River Formation can’t be fully understood, including what the real cause of the contamination of Pavillion residents’ drinking water.

“The science is just pathetic,” Spencer said of the way DEQ has begun using samples from drinking water wells, instead of drilling scientific monitoring wells.

“It just died at the mere mention of fracking, which isn’t as much of the problem as these improperly constructed gas wells.”

While not admitting that there’s a problem, Encana, the gas company that owns the wells, has been delivering water to some of the affected farmers and ranchers. This duplicity shields them from having to find a real solution, such as simply drilling a new municipal water well a few miles outside of the gas field and pumping water in. This type of solution isn’t unprecedented, nor is it particularly expensive in the scope of Wyoming water projects.

Unfortunately, in the efforts to cover up the fracking contamination, Wyoming has enabled the industry to avoid fixing problems it’s caused through bad practices, and left residents without clean water.

“As a geologist, it’s really frustrating to see how it’s played out” Spencer said. “It’s clear to me that the reason that not much is happening here is political pressure. Everyone in Wyoming knows that groundwater is probably our most important resource. To let this go on for 10 or 15 years and these people still have no water except for a few bottles delivered once a week is just not right.”

Refer also to:

Compare Encana/Ovintiv’s methane contamination at Pavillion to Rosebud:

2016: How creative will frac fraud get? Wyoming regulator dumps frac blame on nature, copy cats Alberta regulators, government, Research Council (now Alberta Innovates), ignores red flag indicators of petroleum industry contamination, ignores that Encana frac’d drinking water aquifers like Encana did at Rosebud

The researchers found instances of water bubbling up at well sites and complicating oil and gas production. ![]() At Rosebud, Encana’s own investigation found fresh water gushing into Encana/Ovintiv’s gas well illegally frac’d into the community’s drinking water aquifers at a rate of 8,000 litres a day, ruining the gas well and resources at that well, quickly followed by contaminated water wells across the community, including some running dry. AER looked the other way, instead of enforcing the laws in place at the time to prevent such harm and waste.

At Rosebud, Encana’s own investigation found fresh water gushing into Encana/Ovintiv’s gas well illegally frac’d into the community’s drinking water aquifers at a rate of 8,000 litres a day, ruining the gas well and resources at that well, quickly followed by contaminated water wells across the community, including some running dry. AER looked the other way, instead of enforcing the laws in place at the time to prevent such harm and waste.![]() “One of the reasons this is important is that it shows ways that fracking fluids can migrate upward to water wells much faster than people had thought,” Jackson said.

“One of the reasons this is important is that it shows ways that fracking fluids can migrate upward to water wells much faster than people had thought,” Jackson said.

… “Decades of activities at Pavillion have put people at risk,” Jackson said.

… “We’ve shown clear evidence of contamination to the aquifer itself,” Jackson said.

Slides above from Ernst presentations

“The way I read the EPA report, the surface casings were too short and that the cementing was inadequate and then they fracked at very shallow depths. It’s almost negligence,” says [isotopic fingerprint expert] 67-year-old [Karlis] Muehlenbachs….

![]() Encana frac’d much more shallow at Rosebud, including directly into the community’s drinking water aquifers.

Encana frac’d much more shallow at Rosebud, including directly into the community’s drinking water aquifers.![]()

“They’ll frack each well up to 20 times. Each time the pressure will shudder and bang the pipes in the wellbore. The cement is hard and the steel is soft. If you do it all the time you are going to break bonds and cause leaks. It’s a real major issue.”…

Whenever methane leaks from one well into a neighboring wellsite, “industry says let’s fix the leaks,” says Muehlenbachs. “But as soon as the leaks enter groundwater, everyone abandons the same logic and technology and says it can’t happen and the denials come out.

In Alberta, it’s almost a religious belief that gas leaks can’t contaminate groundwater.”… Asked if Alberta’s oil patch regulator or B.C.’s Oil and Gas Commission had approached one of the world’s leading experts on how to fingerprint leaking gases from gas formations, Muehlenbachs replied quickly. “No,” said Muehlenbachs. “No one pays any attention to me. The Alberta regulators are only interested in optimizing production.”