I expect Zionist-led pro-genocide, anti-Indigenous provincial and federal gov’ts (e.g. BC, Alberta, SK, Ontario, Harper’s Pierre Picklehead-led CPC, Quebec etc.) won’t honour or abide by this ruling but it’s a relief to see something just and fair come out of our secretive Zionist pro-genocide, anti-Black, anti-Palestinian supreme court of Canada (that knowingly lied in their ruling in Ernst vs AER and treated our constitution, me and my case like shit).![]()

Cindy Blackstock@cblackst:

Supreme Court says Indigenous children win! Now governments need to honour it!

@profamirattaran:

Massive win for the Indigenous.

Humiliation for greedy Quebec, who never should have sued.

Bottom line: federalism must bow to the s. 35 constitutional rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. I love it.

Supreme Court of Canada @SCC_eng Feb 9, 2024:

The Court has dismissed the AGQ’s appeal and allowed the AGC’s appeal in Reference re An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families. It ruled that the federal act was constitutional. Read our plain-language summary here: https://scc-csc.ca/case-dossier/c

Gib van Ert@gibvanert:

Reading this today, I think of the decades of work by Indigenous peoples campaigning for an international declaration of their rights, and the years of further work to achieve recognition of the UNDRIP in BC and federal law. Much more work lays ahead. But…

Mark Warner@MAAWLAW:

Was the decision based on UNDRIP or Section 35 of the Charter?

@gibvanert:

Both but UNDRIP much more prominent. …

Mark Warner@MAAWLAW:

OK. I will need to read it. I think there are some recent BC mining decisions that made a more direct link, but if the SCC here is pointing to an actual statute passed by Parliament “inspired” by UNDRIP that seems different to me at first glance.

Mark Warner@MAAWLAW Sept 27, 2023:

“The #Gitxaala nation claimed the lack of consultation for #mining rights on its lands was inconsistent with the Constitution and both the BC govt’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

“The provincial government, however, told the court that BC’s adoption of the UN’s declaration didn’t actually bring it into law that could be enforced in court, but only set out the government’s” commitment to reconciliation.”

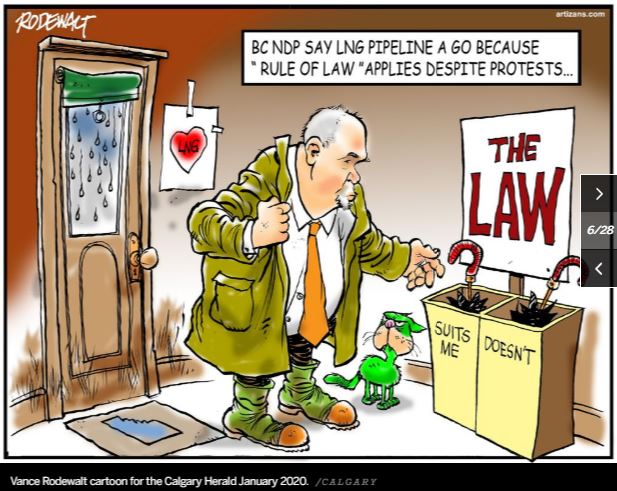

![]() “Commitment” – there’s that magical word again, used by gov’ts, regulators, companies, etc. to con us and escape everything.

“Commitment” – there’s that magical word again, used by gov’ts, regulators, companies, etc. to con us and escape everything.![]()

“Justice Alan Ross [said] the case was… ‘the first judicial consideration of the legal effect of BC’s Declaration Act. He found that the First Nations were not entitled to any court-granted relief under the UN declaration or B.C.’s legislation that adopted it.” #compliance

Supreme Court declares Indigenous child welfare law constitutional, High court dismisses Quebec’s challenge to the legislation by Brett Forester, CBC News, Feb 09, 2024

…

The high court sided with the Canadian government in a decision rendered Friday morning, reversing a Quebec Court of Appeal decision to declare the law partly unconstitutional.

“The act as a whole is constitutionally valid,” the court concluded.

“Developed in co-operation with Indigenous Peoples, the act represents a significant step forward on the path to reconciliation.”

Bill C-92, An Act Respecting First Nations, Métis and Inuit Children Youth and Families, became law in 2019. It affirms Indigenous nations have jurisdiction over child and family services and outlines national minimum standards of care.

…

The entire nine-judge bench heard the case, though retired![]() What bullshit reporting is this? Russ Brown stepped down in 2023 in disgrace because of his alleged drunken hanky panky in the USA being investigated by the self regulator of judges, Canada’s judicial council

What bullshit reporting is this? Russ Brown stepped down in 2023 in disgrace because of his alleged drunken hanky panky in the USA being investigated by the self regulator of judges, Canada’s judicial council![]() justice Russell Brown didn’t participate in its final disposition. The reasons are authored by the court as a whole and not any one judge.

justice Russell Brown didn’t participate in its final disposition. The reasons are authored by the court as a whole and not any one judge.

NigelBankes@NdbYyc1305:

Premiers Moe and Smith might want to read today’s SCC Reference decision [97]: “It is trite law that Parliament can bind the Crown in right of the provinces [so long as it acts] within areas of federal jurisdiction.”

The Supreme Court hits a home run on reconciliation, On the division of powers, on reconciliation, and on arguments about ‘constitutional architecture’ by Emmett Macfarlane, Feb 10, 2024, Declarations of Invalidity

Never let it be said that I only ever criticize the Supreme Court.

Yesterday, in a landmark decision, the Court upheld federal legislation giving (that is, returning) effective control over children’s welfare to Indigenous Peoples. It did so while writing as “The Court” rather than authorship of particular judges, something that sometimes signals the importance of a decision.

The Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families establishes national standards and principles in the context of ensuring the provision of culturally appropriate child and family services across Canada. This is a commitment, the Court recognized, that flows from the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and is grounded in the right to self-government under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 (although the Court declined to elaborate on the precise scope of section 35 with respect to self-government authority over child welfare).

But the law was subject to a challenge by the Government of Quebec, by way of a reference to its Court of Appeal. Quebec argued that the law was an intrusion into provincial jurisdiction, and that it was an affront to the “constitutional architecture” because it stood as a unilateral amendment of the Constitution (a deeply ironic assertion given that province’s recent forays into actually and unconstitutionally asserting the power to unilaterally amend the Constitution).

The Court of Appeal partially adopted some of Quebec’s arguments by determining that while much of the law was constitutionally valid, the provisions that provide Indigenous peoples priority over provincial laws relating to child and family services were invalid because they would not be “federal laws enacted under s. 91 and subject to the doctrine of federal paramountcy, but rather Aboriginal laws that serve Aboriginal imperatives.” (see para. 35, citing para. 540 of the QCCA opinion).

Thankfully, the Supreme Court disagreed, upholding the Act in its entirety. It characterized the pith and substance of the Act as seeking to protect “the well-being of Indigenous children, youth and families by promoting the delivery of culturally appropriate child and family services and, in so doing, advances the process of reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples” (para. 41). As such, the Act “falls squarely” within the federal Parliament’s authority under section 91(24) (“Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians”) (para. 93).

The Court, consistent with longstanding division of powers jurisprudence, recognized the overlapping spheres of authority that often result in the modern context, finding that the imposition of national standards by the federal level within its sphere authority did not obliterate provincial authority over child and family services generally. The federal government is free to impose national standards within its area of authority, and the double aspect doctrine allows for “concurrent application” of federal and provincial legislation in relation to specific policies and facts (para. 98). In fact, the Court found the federal law consistent with the need for cooperative efforts between both levels of government to advance reconciliation and ensure child welfare in the Indigenous context (para. 99). The law does not eliminate or remove the provincial role, even with respect to Indigenous children, let alone its own inherent jurisdiction. But the national standards do apply to the provincies.

The Court also rejected the claim by Quebec that the legislation illegitimately sought to establish a new Indigenous right under section 35. (Here, I appreciated the Court’s statement that “Only s. 44 provides for the possibility of unilateral amendments [to the Constitution of Canada] by Parliament” – implicitly affirming that provinces cannot unilaterally amend the national constitution; please, someone challenge Quebec’s Bill 96 and Bill 4!). And of course, it found that that’s not what the federal law does; it simply affirms – in an ordinary statute, not a purported constitutional amendment – its understanding of section 35 and the right to self-government (para. 107-110).

Finally, the Court also rejected the argument that the federal incorporation of Indigenous laws somehow constituted an alteration to the constitutional architecture. Instead, the Court pointed out that this sort of incorporation by reference is relatively common and a valid practice. Federal paramountcy applies where such valid laws come into conflict with otherwise valid provincial law.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of this decision. If the federal government had lost, it would not only have been a serious blow to an important aspect of of Indigenous self-government and rights, it would have also been a serious blow to the broader effort at reconciliation.

This is because in the absence of our ability to enact major constitutional reform, this sort of federal legislative “devolution” of authority and jurisdiction to Indigenous governments is likely the best path forward to upholding and protecting a sphere of meaningful sovereignty for Indigenous peoples. It is consistent with an approach to ‘treaty federalism’ that would finally, over time, remove the colonial imposition of federal oversight and recognize Indigenous laws over wide spheres of policy, from family law to land use to education, etc.

The Court recognized that legislative reconciliation was a valid and possibly more efficient path than the more complex, expensive, and dramatically slower options of modern treaty negotiations or constitutional litigation. But it is also an (imperfect) alternative to formal amendment to recognize Indigenous sovereignty or, perhaps eventually, an ‘Aboriginal order of government’.

The Quebec challenge, if successful, would have introduced a dramatic barrier to an efficient model for advancing reconciliation. And there was a valid reason to worry that the Court might have opted for a more “cooperative federalism” approach that prevents this sort of positive federal action (action, which followed, it is worth noting, consultation with Indigenous communities), by asserting that provinces needed to approve or also legislate in order to recognize Indigenous self-government over child welfare. Thankfully, the Court instead recognized federal authority to effectively devolve its own jurisdiction in a more direct and efficient manner.

The rejection of the ‘constitutional architecture’ arguments were also beneficial for hopefully dampening future attempts at recourse to that nebulous concept for challenging legislative acts. It is, as I have written at length, an ambiguous and largely unhelpful concept for constitutional adjudication.

In short, the Court offered a definitive, clear, coherent, and straightforward statement on the division of powers and reconciliation that should be applauded for both its logic and the ultimate outcome. A good day for the Court indeed.

![]()

Refer also to:

Art above by Indigenous scholar and law prof, Val Napoleon

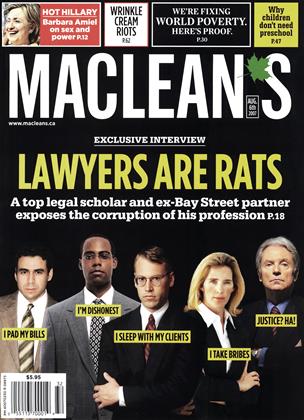

… The whole question of the values behind the rules of the legal system is not on the whole of great interest to law schools or the legal profession. And there’s an additional point: lawyers are taught to manipulate the rules…. ![]() Many politicians are lawyers; lawyers become judges.

Many politicians are lawyers; lawyers become judges.![]()

If you’re taught how to manipulate rules, you lose respect for them, and that leads to a kind of arrogance: I’m bigger than the rules, I’m not the average man on the street who needs to be law-abiding because I know how to get around the rules. And there may be just a touch of the more common form of arrogance, too, which is “I’m smarter than they are, they’ll never catch me.”

… The disciplinary process of the law societies in this country is deeply flawed.

… I think Canada really has to get its act together. Look at the reforms in the U.K., which woke up some years ago to this problem and [adopted] quite sweeping reforms that largely removed self-regulation from the legal profession.

Why in heaven the same sort of reforms are not under consideration in this country I do not know, except that self-regulation is regarded with quasi-religious fervour. … ![]() Canada’s judges are also self-regulated, as is the oil, gas and frac industry

Canada’s judges are also self-regulated, as is the oil, gas and frac industry![]()