Nigel Bankes@NdbYyc1305:

This decision is now available: Altius Royalty v Alberta, https://canlii.ca/t/k3vp2. Good news. It won’t help the coal companies (Cabin Ridge, Atrium, Montem, Northback/Grassy) in their claims to compensation ‘gst GoA. #ableg

Jackie Seidel, PhD@JackieSeidel1:

great. whew.

Alberta Appeal Court dismisses coal company lawsuit alleging expropriation by The Canadian Press, April 4, 2024, Yahoo! News

EDMONTON — Alberta’s top court is dismissing a coal company’s request for compensation over government policies to phase out coal power.

Altius Royalty Corp. was asking for $190 million in compensation, arguing federal and provincial moves to end such generation over climate and health concerns was a type of expropriation.

Altius, which owns the Genesee coal mine that feeds the Genesee power plant, lost in Court of King’s Bench but took its case to the Alberta Court of Appeal.

In its decision released today, the Appeal Court says Altius argued the regulations and agreements that led to the end of coal-fired power gave governments the benefit of lower health-care and environmental costs.

Because that benefit can be assigned a dollar figure, Altius argued that qualifies it to compensated.

But the judges ruled those benefits accrue to the public, not the state.

“Canada’s prediction of the health and environmental benefits resulting from the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions describes benefits to the public, not … an ‘advantage’ flowing to the state,” they wrote.

They found neither Canada nor Alberta received any economic benefit from Altius’ property.

The court found that allowing Altius’ appeal would kneecap the government’s ability to regulate.

“Extending the concept of ‘advantage’ as the appellant suggests could have a tremendous impact on the public purse and legislative decision making,” they write.

“It is questionable whether the application of the common law can, or should, intrude to this extent on decisions made by legislators in the public interest.”

***

In the Court of Appeal of Alberta

Citation: Altius Royalty Corporation v Alberta, 2024 ABCA 105

Date: 20240404

Altius Royalty Corporation, Genesee Royalty Limited Partnership

and Genesee Royalty GP Inc.

Appellants

His Majesty the King in right of Alberta and Attorney General of Canada

Respondents

– and –

Ecojustice Canada Society

Intervener

_______________________________________________________

The Court:

The Honourable Justice Elizabeth Hughes

The Honourable Justice Jolaine Antonio

The Honourable Justice Anne Kirker

_______________________________________________________

The Honourable Justice J. C. Price

Dated the 22nd day of April, 2022

Filed the 8th day of June, 2022

(2022 ABQB 255, Docket: 1801-16746)

_______________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________

Introduction

[1] The appellants own a royalty interest in a coal mine. They claim their interest has been constructively expropriated by the actions of the respondent governments and they are owed compensation. An applications judge and a chambers judge summarily dismissed the appellants’ claims on the basis the test for constructive expropriation had not been met. The appellants appeal, seeking the restoration of their action.

Background facts

[2] The appellants are part of a corporate family (collectively called Altius) holding royalties in mines across Canada. Relevant to this appeal is their 2014 acquisition of royalty interests in the Genesee coal mine. The coal from the mine fuels the Genesee power plant which generates electricity in Alberta.

[3] In 2012, federal regulations established a performance standard for coal-fired power plants. Based on those regulations, the dates at which the three coal-burning units at the Genesee power plant would reach the end of their useful lives were calculated to be in 2039, 2044, and 2055.

[4] After the 2015 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which resulted in the Paris Agreement, the government of Canada amended the regulations to require the performance standard for coal-fired plants to be met no later than 2030. The government of Alberta introduced its Climate Leadership Plan to phase out coal-fired electricity generation emissions by 2030. As part of that plan, Alberta entered into an Off-Coal Agreement with the owners of the Genesee power plant and other coal powered plant owners: the owners of electricity generation plants agreed to end emissions by 2030 and Alberta agreed to make transition payments to them. The appellants are not parties to the Off-Coal Agreement.

[5] In 2018, the appellants filed a statement of claim against the respondents, Canada and Alberta, alleging they had constructively expropriated their royalty interest without compensation. In 2020, the respondents applied to summarily dismiss the action or to have it struck for prematurity. In response, the appellants filed the affidavit of Ben Lewis, sworn September 28, 2020, and cross-applied to further amend their statement of claim.

[6] In January 2021, an applications judge allowed the appellants’ proposed amendments, declined to strike out the claim for prematurity, and summarily dismissed the entire action. After concluding that summary disposition was appropriate and the action was not premature, the applications judge considered the test for constructive expropriation or constructive taking[1] as set out in Canadian Pacific Railway Co v Vancouver (City), 2006 SCC 5, [2006] 1 SCR 227 [CPR], which required (1) an acquisition of a beneficial interest in the property or flowing from it, and (2) removal of all reasonable uses of the property. The applications judge found the first part of the test was not met and granted the respondents’ applications for summary dismissal: Altius Royalty Corporation v Alberta, 2021 ABQB 3.

[7] All parties appealed to a chambers judge.

[8] The chambers judge upheld the applications judge’s decisions regarding prematurity and the amendments to the statement of claim. She also upheld summary dismissal on the basis that the first branch of the two-part test in CPR was not met: Altius Royalty Corporation v Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Alberta, 2022 ABQB 255 [Reasons].

[9] The appellants appeal the chambers judge’s decision on summary dismissal. They allege she erred in (i) stating the test for constructive expropriation and (ii) finding the test for summary dismissal was met.

[10] After the notice of appeal was filed, the parties agreed to stay the appeal process pending the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in Annapolis Group Inc v Halifax Regional Municipality, 2022 SCC 36 [Annapolis] which addressed the issue of constructive expropriation. The Supreme Court rendered its decision in Annapolison October 21, 2022.

Standard of review

[11] The chambers judge’s assessment of the facts, the application of the law to those facts, and the ultimate determination on whether summary resolution is appropriate are all entitled to deference: Weir-Jones Technical Services Incorporated v Purolator Courier Ltd, 2019 ABCA 49 [Weir-Jones] at para 10, citing Hryniak v Mauldin, 2014 SCC 7 at paras 81-84, [2014] 1 SCR 87; Amack v Wishewan, 2015 ABCA 147 at para 27, 602 AR 62.

[12] The test for constructive expropriation, as a question of law, is reviewed on a standard of correctness: Housen v Nikolaisen, 2002 SCC 33 at para 8.

Analysis: constructive expropriation

[13] The chambers judge’s decision to summarily dismiss the appellants’ claim turned on her conclusion that “[t]he first requirement of the test for de facto expropriation has not been and cannot be made out as there has not been an acquisition of a beneficial interest in property or flowing from it”: Reasons at para 77(b). The appellants assert she reached this conclusion in error because a constructive expropriation does not require that the Crown acquire a beneficial interest;the acquisition of an advantage will suffice. Here, they say, the respondent Crowns acquired an advantage.

[14] The appellants largely support their position by citing select passages from Annapolis. However, read as a whole, Annapolis does not assist the appellants.

[15] In Annapolis, the Supreme Court of Canada interpreted CPR. In CPR, the Supreme Court of Canada stated at paragraph 30:

For a de facto taking requiring compensation at common law, two requirements must be met: (1) an acquisition of a beneficial interest in the property or flowing from it, and (2) removal of all reasonable uses of the property [citations omitted].

[16] Regarding the first step, the majority in Annapolis noted the interest acquired by the Crown, according to CPR, could be a beneficial interest in expropriated property, or an interest flowing from the property: Annapolisat para 25. The majority used the expansive term “advantage” to underscore that the focus is not necessarily limited to traditional property interests.

[17] The majority was motivated by the need to retain a distinction between de jure and de facto expropriation. A de jure (or formal) expropriation involves the acquisition of title, while a de facto (or constructive) expropriation involves the acquisition of a proprietary interest without legal title, usually through regulatory action. The Annapolis majority was concerned that if “beneficial interest” were too narrowly defined, the category of de facto or constructive expropriation would be read out of existence: para 39-40. Therefore, it emphasized that “beneficial interest” is not confined to its technical meaning.

[18] In its analysis of the first CPR step, the majority did not otherwise comment on the meaning of “acquiring” an interest “in property”. Importantly, the majority repeatedly stated its intent was not to change the law, but merely to clarify the test developed in line of cases leading to CPR. See, for example, paras 22, 25, 40-41, 44.

[19] To state the obvious, expropriation pertains to property. Without a property interest, there can be no expropriation, whether de jure or constructive. Here, for example, the appellants have taken pains to show their royalty interest is proprietary rather than merely contractual.

[20] The concept of “acquisition” in the CPR/Annapolis test must be understood as pertaining to property. In the words of Annapolis, a constructive expropriation may arise where a “beneficial interest – understood as an advantage – in respect of private property accrues to the state, which may arise where the use of such property is regulated in a manner that permits its enjoyment as a public resource”: at para 4 [emphasis added].

[21] Regardless of how the interest is characterized, there must be some correspondence between the expropriated interest and the acquired interest. The cases of CPR, Manitoba Fisheries Ltd v The Queen, 1978 CanLII 22 (SCC), [1979] 1 SCR 101 [Manitoba Fisheries], The Queen in Right of the Province of British Columbia v Tener, 1985 CanLII 76 (SCC), [1985] 1 SCR 533 [Tener], and Mariner Real Estate Ltd v Nova Scotia (Attorney General), 1999 NSCA 98 [Mariner], all demonstrated such correspondence.

[22] In CPR, the Supreme Court of Canada found noconstructive expropriation of CPR’s land by the City of Vancouver. By way of by-law, the City had imposed a “development freeze” to ensure “the land [would] be used or developed in accordance with [the City’s] vision, without even precluding the historical or current use of the land”. The Court held this was “not the sort of benefit” that could be construed as an expropriation: CPRat para 33. While CPR was prevented from developing the land in certain ways, the City did not acquire any beneficial interest in it as a result.

[23] In Manitoba Fisheries, the Supreme Court of Canada found a constructive expropriation when federal legislation granted a fish export monopoly to a Crown corporation and delegated to it the power to grant licences. When refused a licence, a private fish export company went out of business. The legislation had the effect of depriving the company of its goodwill – a form of intangible property – and transferring it to the monopolistic Crown corporation: p 118. In finding a de facto expropriation had occurred, the Supreme Court emphasized the correspondence between the acquisition and the deprivation, saying the company’s lost goodwill was “the same goodwill” that was “acquired by the federal authority”. In other words, the company was “deprived of property which was acquired by the Crown”: p 110 [emphasis added].

[24] In Tener, the question of constructive expropriation arose against a complex legal and historical backdrop. In short, private owners had been granted mineral rights on lands within a provincial park. New legislation prohibited exploration for or development of minerals in the park. Thus, the owners were deprived of access to the minerals, though they retained title to the minerals. The Crown gained the right to exclude the owners’ exercise of their mineral rights. It did not regain title to the minerals but it effectively recovered part of the interest it had granted to the owners. The lost and gained uses corresponded and were of a sufficiently proprietary nature to ground a constructive taking.

[25] In Mariner, the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal found the provincial Crown did not constructively expropriate privately owned beach property by imposing stringent conservation regulations which prohibited a certain type of development. Cromwell JA (as he then was) affirmed that a de facto taking requires “an acquisition as well as a deprivation”, and that the acquisition be proprietary in nature: para 98 [emphasis in original]. He emphasized that both Tener and Manitoba Fisheries required the acquisition to correspond to the deprivation, noting that in Tener, “the Crown re-acquired in fact, though not in law, the mineral rights”, and in Manitoba Fisheries, “the asset which was, in effect, lost by Manitoba Fisheries was the asset gained, in effect, by the new federal corporation”: at paras 95 and 97.

[26] Regulation that enhances the value of public land does not on its own constitute the acquisition of an interest in land. Cromwell JA concluded at paragraph 99 of Mariner that “for there to be a taking, there must be, in effect… an acquisition of an interest in land and that enhanced value is not such an interest”.

[27] This underscores the principle that “[i]n takings law, only those rights that are proprietary and vested . . . are compensable” (§ 5:8) and that “Canadian law recognizes that governments have the ability to greatly restrict the potential uses of property without triggering a right to compensation” (§ 5:13): K. Horsman and G. Morley, eds., Government Liability: Law and Practice (loose‑leaf). As confirmed in Annapolis, “not every instance of regulating the use of property amounts to a constructive taking”: para 19.

[28] It is thus clear from the Supreme Court of Canada cases, including Annapolis, that for regulatory action to amount to a constructive expropriation, the expropriated interest must be proprietary; the acquired interest need not be a conventional property interest but must be proprietary enough to be capable of “acquisition”; and while the acquired interest need not correspond exactly, as it would in a de jure expropriation, it must flow from or correspond in some way to the expropriated interest: CPR at para 30.

Application to the facts

[29] At issue in this appeal is the first requirement in the CPR/Annapolis test: an acquisition of a beneficial interest in the property or flowing from it, or as stated in Annapolis, an acquisition of an advantage in respect of private property. Here, the appellants assert the advantage flowing to governments is “avoided healthcare and environmental expenses”. They seem to say that because the governments assigned a dollar figure to the healthcare and environmental benefits, the alleged advantage is a proprietary one.

[30] We disagree. “Quantifiable” does not mean “proprietary”.

[31] In its Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement accompanying Regulations Amending the Reduction of Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Coal-fired Generation of Electricity, SOR/2018-263, part of Canada Gazette, Part II, Volume 152, Number 25, Canada predicted the expected reduction in greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the amended regulations over the period 2019 to 2055 would result in $1.3 billion in health and environmental benefits from air quality improvements. The health benefits were not health care cost savings but “measures of improvement in quality of life, resulting from better health.” The environmental benefits consisted of avoided climate change damage including “increased crop yields, reduced surface soiling and improvement in visibility” which were quantified based on their “social cost values” to Canadians.

[32] Canada’s prediction of the health and environmental benefits resulting from the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions describes benefits to the public, not, as expressed by the majority in Annapolis, “an ‘advantage’ flowing to the state”: para 38. From cases decided before Annapolis, in reliance on precedents which Annapolis did not change, courts have concluded that a generalized public benefit cannot constitute an acquisition flowing to the Crown. For example, in Club Pro Adult Entertainment Inc v Ontario (Attorney General) (2006), 27 BLR (4th) 227, 2006 CanLII 42254 (ONSC) at para 82; aff’d 2008 ONCA 158, the court wrote, “[i]t is too far fetched to suggest that the public gets a benefit from [anti-smoking regulations] such that there has been a ‘taking’ by the province”. In Magnum Machine Ltd (Alberta Tactical Rifle Supply) v Canada, 2021 FC 1112 at para 39, the court held achievement of the public purpose behind a regulation was “not an asset the government acquired”.

[33] More importantly, the appellant’s interpretation would unduly broaden the scope of the CPR/Annapolis test.

[34] All government regulation and legislation is intended to be in the public interest. Extending the concept of “advantage” as the appellant suggests could have a tremendous impact on the public purse and legislative decision making. It is questionable whether the application of the common law can, or should, intrude to this extent on decisions made by legislators in the public interest. Even academic commentators who were unsatisfied with the acquisition requirement in the CPR test urged courts to apply the concept of advantage narrowly “so to contain the risk that the financial exposure of public authorities”: Peter Hogg & Wade Wright, Constitutional Law of Canada, 5th Edition (Toronto: Thomson Reuters Canada, 2020) (WL Can) at § 29:8. At its core, “the weighing of social, economic, and political considerations to arrive at a course or principle of action is the proper role of government, not the courts”: R v Imperial Tobacco Ltd, 2011 SCC 42 at para 87.

[35] Cases decided since Annapolis indicate the potential for proliferation of expropriation claims based on an overly broad reading of what constitutes an advantage. For example, in Kalu v His Majesty the King, 2023 ONSC 6623, the plaintiff attempted to bring a constructive expropriation claim on behalf of Ontario residential landlords. She asserted the Residential Tenancies Act, 2006, SO 2006, c 17, permitted “perpetual delay” by the Landlord and Tenant Board, thereby depriving landlords of property while tenants remained in place without paying rent. The plaintiff argued the Crown would receive the following benefits: (i) a reduction in the cost of providing public housing while non-paying tenants remained in place; (ii) reduced spending on public health while fewer people were unhoused; (iii) reduced spending on welfare programs while potential recipients lived rent-free; and (iv) “improved political reputation”. The court held it was plain and obvious the claim could not succeed because, even if it could be argued that certain property rights were limited or even eliminated by the legislation, no property rights were acquired by the Crown. The claim was struck.

[36] The majority in Annapolis expressly held, “not every instance of regulating the use of property amounts to a constructive taking”: para 19. As shown by the authorities discussed in Annapolis and as stated in Mariner, “de facto expropriations are very rare in Canada”: para 83. Under the appellants’ reasoning, they would become frequent if not ubiquitous.

[37] We conclude mere public benefit cannot constitute an interest or advantage acquired by the Crown within the meaning of the first step of the CPR/Annapolistest. Further, a private property advantage could not satisfy this step of the test unless it could be found to correspond to the allegedly expropriated property interest. Applied here, and mirroring the words of Annapolis at paragraph 4, the anticipated health and environmental benefits cannot be understood as advantages in respect of private property accruing to the Crown, resulting in the Crown’s enjoyment of the appellants’ royalty interests as a public resource.

[38] With regard to the respondent Canada, the action at the root of the alleged constructive expropriation was a change to the federal regulatory scheme governing coal-fired power plants. Canada regulated with the intention of advancing important public policy objectives to benefit the public. However, the achievement of the public purpose behind the regulation was not an advantage in respect of private property accruing to the Crown in right of Canada.

[39] Alberta did not take any legislative or regulatory action. It entered into a private agreement with owners of coal-fired electricity generating plants, which provided for voluntary payments by Alberta for capital investments in the electricity generators and the owners’ agreement to cease coal emissions from their plants. The agreement did not remove any property rights or interests from the appellants. The appellants’ loss of royalty payments resulted from the plant owner’s decision to cease operations.

[40] Like Canada, Alberta received no advantage flowing from the appellants’ property. The appellants submit Alberta received benefits of the sort described in Canada’s Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement. But for the same reasons set out above, such public benefits do not satisfy the requirement that the Crown in right of Alberta acquired an advantage resulting from its actions.

[41] The chambers judge did not err in finding the respondents did not acquire an advantage. As the governments acquired nothing, the appellants fail to meet the first requirement of the test set out in CPR and Annapolis.

[42] We need not address the other issues raised by the appellants. The test for summary judgment has been met as the respondents showed that there is no merit and no genuine issue requiring a trial: Weir-Jones at paragraph 47.

[43] Accordingly, we find no reviewable error in the chambers judge’s decision to summarily dismiss the claim.

Conclusion

[44] The appeal is dismissed.

Appeal heard on November 9, 2023

Memorandum filed at Calgary, Alberta

this 4th day of April, 2024

Refer also to:

Another post for you Rob Schwartz!

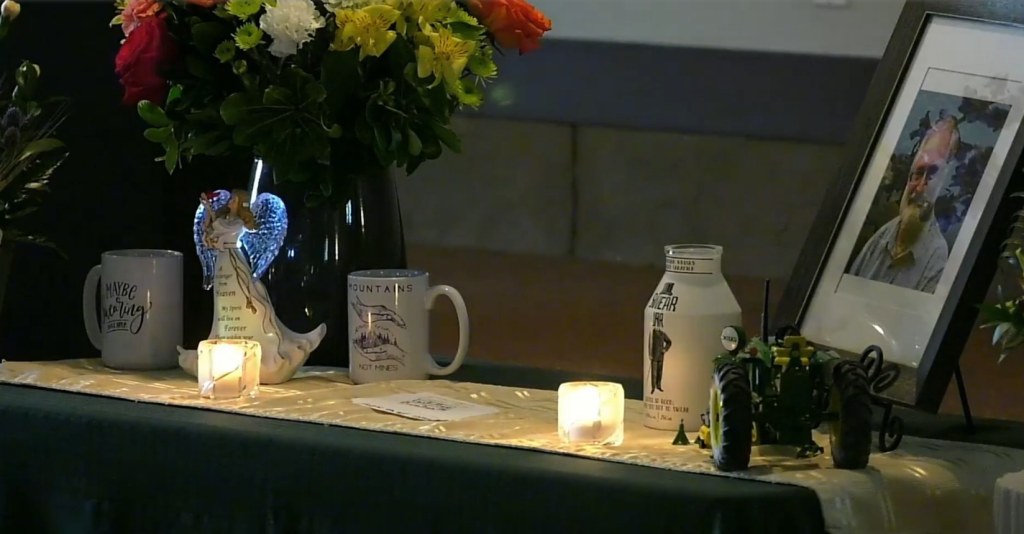

July 2023: Rob’s celebration of life. Note the “Mountains not Mines” mug to the right of the angel. Rob was vehemently opposed to the destruction of Grassy Mountain to enrich an Australian billionaire while destroying drinking water for many Canadians.

“By any responsible account,” Chief Justice Castille wrote, “the exploitation of the Marcellus Shale Formation will produce a detrimental effect on the environment, on the people, their children, and the future generations, and potentially on the public purse, perhaps rivaling the environmental effects of coal extraction.”