After the study was submitted for publication:

DICKINSON, N.D. (AP) … The oil boom initially was met by an “organic workforce” of western North Dakotans with experience in oil field jobs elsewhere, but as the economy reeled from the Great Recession, thousands of people flocked to the Bakken oil field from other states and even other countries to fill high-wage jobs, Sanford said.

Technological advances for combining horizontal drilling and fracking — injecting high-pressure mixtures of water, sand and chemicals into rocks — made capturing the oil locked deep underground possible.

“People came by planes, trains and automobiles, every way possible from everywhere for the opportunity for work,” Council President Ron Ness said. “They were upside down on their mortgage, their life or whatever, and they could reset in North Dakota.”

But the 2015 downturn, coronavirus pandemic and other recent shocks probably led workers back to their home states, especially if moving meant returning to warmer and bigger cities, Sanford said.

Workforce issues have become “very acute” in the last 10 months, Ness said.

Ness estimated there are roughly 2,500 jobs available in an oil field producing about 1.1 million barrels per day. Employers don’t advertise for every individual job opening, but post once or twice for many open positions, he said.

An immigration law firm told Ness that Uniting for Ukraine would fit well for North Dakota given its Ukrainian heritage, similar climate and agrarian people, he said. …

***

2024 01 18: Extreme cold weather causing oil spills in North Dakota; 60 reports over past week

***

How an oil boom in North Dakota led to a boom in evictions, New study links surge of oil workers to long-term residents losing their homes by Siri Chilukuri Environmental Justice Fellow, Jan 19, 2024, Grist

This story was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

The sign that welcomes people into Williston, North Dakota, has an inscription at the bottom: “Boomtown, USA.” It’s one way of characterizing the now infamous oil boom that doubled the city’s population between 2010 and 2020, with an influx of workers eager to get to the oilfields. All those newcomers led to another boom: an increase in evictions.

New research from Princeton University sheds light on the relationship between fracking and evictions, finding that in Williams County, the surrounding area of Williston, eviction filings rose from 0.002 percent in 2010 to over 7 percent by 2019. In the same time period, fracked oil in the area grew from 300,000 barrels of oil a month to 7½ million barrels a month.

Williston is not alone. Other research backs up the connection between fracking and evictions, since the industry often draws an influx of new, temporary residents to places like Midland, Texas, or Lycoming County, Pennsylvania. This is because fracking often leads to a plethora of high-paying jobs. In the meantime, long-time residents aren’t always able to access the wealth that these areas produce and are left to bear out the consequences long after the boom is over.

“Renters are almost invariably going to lose out in this equation,” said Carl Gershenson, lead author and director of Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

Existing residents can often be displaced because landlords can charge short-term renters exorbitant rates instead of the relatively affordable prices that long-term renters pay for the same property, according to Gershenson.

“A savvy landlord realizes that a lot of these people are coming for the season,” said Gershenson. “So it’s very common to, say, switch over a place that had been on an annual lease to monthly leases. And now you’re renting out rooms instead of a whole house. In some cases, you can fit 10 or 12 people, you know, into a house that was renting out to one family.”

He also notes that not only do evictions displace residents, but can be a destabilizing force for the people that have experienced them.

“Evictions are not just the consequence of poverty, but really are one of the leading causes of poverty,” said Gershenson.

People who have experienced evictions often also experience mental and physical health issues more than their peers who have never been evicted.

Another hurdle to overcome is that smaller municipalities aren’t often equipped to handle the influx, or the developers that follow rapid population increases. So things like long-term planning fall by the wayside as cities and towns try to cope with the immediate increased needs for municipal services.

“It’s an investment in terms of not only hard infrastructure, like pipes, and electrical and roads, but also human infrastructure, things like law enforcement, things like emergency services, things like social services,” said William Caraher, associate professor of history and American Indian studies at the University of North Dakota.

Caraher also noted that initially, the large presence of man camps, or temporary housing for oilfield workers, posed a problem for community members who did not want the negative stigma associated with the drug use and other issues that arrived with the camps. In response, many cities and towns in this area allowed more development to occur, so that workers could live in a form of permanent housing. But now those places are left with hastily built and overpriced housing.

There are ways to combat displacement, though, and one solution that Caraher points to are increased protections for tenants, which could help keep eviction rates low.

Caraher noted that despite the fact that people in the community did attempt to secure more housing and tenants rights, the pace of the boom was ultimately too much to accommodate lower-income, longer-term residents.

Another option that Gershenson points to is something called a community-benefits agreement, wherein residents can work with companies to determine how any economic development can help long-time residents alongside any new employees drawn to the area for work.

“I think it’s fair that the community captures some of those profits to invest into affordable housing,” he said.

There needs to be better options, said Caraher, to accommodate both workers and communities in boomtowns.

Housing in the U.S. falls between two extremes, either short-term hotels or forever homes, he said. “This kind of gray area in between isn’t ever well established as to how it should operate,”

***

The study:

Fracking Evictions: Housing Instability in a Fossil Fuel Boomtown by Carl Gershenson, Olivia Jin, Jacob Haas and Matthew Desmond, Published online: 04 Dec 2023

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2023.2286640

Abstract

In 2019, North Dakota accounted for 11% of American oil production. Rural counties like Williams County, ND experienced rapid in-migration of oilfield workers and, consequently, acute housing shortages. Williams County provides an excellent opportunity to study the relationship between commodity booms and housing instability because its housing market is tied so tightly to the production of a single commodity. While fracking is often presented as an economic boon to these communities, we show that Williams County has experienced “rural gentrification,” in which long-term residents are displaced by higher-income workers linked to the oilfields. To explore housing instability in an oil boomtown, this project links oil production statistics with evictions data and individual-level address histories. By showing how housing instability increased during the oil boom, this study contributes to our understanding of how rural communities are affected by extractive industry and how housing markets respond to rapid economic changes.

Keywords:

Breakthroughs in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) technology revolutionized global energy markets by allowing the United States to exploit vast, previously inaccessible oil and gas deposits. Political forces lined up behind unconventional oil and gas production because it promised to solve three problems at once: the dependence of the United States and its allies on fossil fuels from the Middle East; deindustrialization and depopulation of America’s Rust Belt and rural communities (cf. Mayer, Malin, et al. Citation2018); and the (debated) promise ![]() disgustingly fed by NGOs lying for frac’ers like law violating Chesapeake, in exchange for multi milllion dollar donations, e.g. Sierra Club

disgustingly fed by NGOs lying for frac’ers like law violating Chesapeake, in exchange for multi milllion dollar donations, e.g. Sierra Club![]() of a climate friendly “bridge fuel” as the world transitions from coal power to renewables. Of course, the resulting fossil fuel boom also promised incredible profits for oilfield service companies, energy companies, and owners of land sitting above energy-rich shale formations.

of a climate friendly “bridge fuel” as the world transitions from coal power to renewables. Of course, the resulting fossil fuel boom also promised incredible profits for oilfield service companies, energy companies, and owners of land sitting above energy-rich shale formations.

Lined up against these powerful geopolitical and macroeconomic forces were thousands of county supervisors, town councils, and landowners who have had to decide whether, and on what terms, to allow oil and gas production into their local communities (Dokshin Citation2016; Jerolmack Citation2021; Jerolmack and Walker Citation2018; Malin Citation2014; Schafft, Borlu, and Glenna Citation2013). In an idealized version of deliberative politics, residents and policymakers would attempt to weigh the environmental and social harms of fracking against the economic benefits they believed would flow into their community.

In practice, however, aggressive tactics by oil and gas companies can fracture communities attempting to reach consensus on these issues (Willow and Wylie Citation2014). Attitudes toward the oil and gas industry often determines how residents feel about allowing fracking into their communities rather than vice versa (Mayer Citation2016). Due to the number of factors in play, even geographically proximate communities can reach different decisions (Dokshin Citation2016, Citation2020).

While fracking debates often revolve around an “economic growth versus the environment” framing, how specific harms and gains will be distributed among community members is equally important. In this article, we consider how fossil fuel production contributes to housing instability among residents of boomtowns through a process of “rural gentrification” (Sherman Citation2021). In particular, we examine the prevalence of court-issued evictions, a leading cause of housing insecurity. Aggregate statistics showing rapid increases of wealth and income in boomtowns may obscure the loss of housing stability among lower- and fixed-income renters.

Before the oil boom took off, North Dakota had an eviction filing rate of 0.002% in 2010, dramatically lower than the national rate of 9.4% (Gromis et al. Citation2022). While North Dakota’s eviction rates were kept low by affordable rents, the state’s weak landlord-tenant laws meant that its residents were vulnerable should the affordability of local rental markets decrease suddenly (Schmidt Citation2016). For example, in North Dakota a landlord can file an eviction against a tenant as soon as three days after a missed rent payment. The law also allows a court summons to be served only three days before an eviction hearing, which makes it difficult for a tenant to obtain legal advice or to rearrange their schedule so as to be present at court (Legal Services Corporation Citation2021). While seemingly minor, these technical aspects of the law are associated with higher eviction rates (Gromis et al. Citation2022).

These legal conditions left the residents of Williams County vulnerable to eviction after rents began to increase along with oil production.

The consequences of evictions for these communities’ long-term health are significant. Housing security is increasingly being recognized as a fundamental determinant of rural community vitality (Cook et al. Citation2009) and individual health outcomes (Cutts et al. Citation2022; Desmond and Kimbro Citation2015; Hatch and Yun Citation2020). Evictions may amplify harms linked to fracking (Beleche and Cintina Citation2018; Jayasundara et al. Citation2018; Opsal, Luzbetak, and O’Connor Shelley Citation2021), such as adverse birth outcomes (Himmelstein and Desmond Citation2021), crime (Gomory and Desmond 2023; Semenza et al. Citation2021), sexually transmitted infections (Niccolai, Blankenship, and Keene Citation2019), and poor general health (Desmond and Kimbro Citation2015). In other cases, evictions may negate the positive effects of fracking by leading to job loss (Desmond and Gershenson Citation2016) or by draining local fiscal capacity (National Low Income Housing Coalition Citation2020).

In short, if the arrival of oil and gas workers disrupts local housing markets, lower-income renters in these communities will become more vulnerable to eviction. In order to assess the effects of a commodity boom on renters, this study focuses on evictions in Williams County, North Dakota. Williams County, located in the northwest corner of the state, was primarily an agricultural community until major oil discoveries in the 1950s began to shift the county’s economic base. The county’s population grew during North Dakota’s first oil boom, which ended in the mid-1980s (State Historical Society of North Dakota Citation2013). The arrival of unconventional oil extraction technologies opened up the Bakken Shale Formation to even more intensive oil production, kicking off a second extraction boom. The largest town in Williams County is Williston, which saw its population double during this boom. Served by Amtrak and an international airport, this otherwise isolated town grew from 14,700 in 2010 to over 29,000 in 2020. Even so, this figure likely undercounts the town’s true population due to the difficulty of counting the many workers drawn to the oil fields who may stay for only a season or find shelter in informal “man camps” (Caraher et al. Citation2017).

Williams County and Williston are ideal sites for a study of the link between commodity booms and housing instability not only because we possess quality administrative data on evictions, but also because of its relative isolation. Unlike other boomtowns in the Marcellus, Barnett, and Permian Basin shale formations, nearly the entirety of observed demographic and economic trends in Williams County can be attributed to the oil boom. We find that William’s eviction filing rates rose from nearly non-existent to greater than 7% over the course of the fracking boom. The majority of those affected by housing instability had residential histories in Williston, suggesting that long-term residents of the area were displaced by the arrival of oilfield workers.

The Political Economy of Natural Resource Production

…

Thinking on the long-term economic consequences of fossil fuel extraction has long centered on theories of the “Resource Curse,” which posits that high returns on resource extraction will crowd out investments in more sustainable forms of economic growth. While much evidence for the Resource Curse is derived from cross-national comparisons of the diversified economies of industrialized nations to the stagnant economies of underdeveloped petrostates (van der Ploeg Citation2011; Sachs and Warner Citation2001), American fossil fuel booms have provided economists the opportunity to assess this thesis in the American context. While these studies often find that resource production results in higher wages and more jobs without destroying productivity in other tradeable sectors (Allcott and Keniston Citation2018; cf. Mayer, Olson-Hazboun, et al. Citation2018), they also find that when the boom gives way to bust, employment and wages drop at a faster rate than they rose during the boom (Black, McKinnish, and Sanders Citation2005). As a result, employment rates and per capita incomes may be lower than they would have been had the boom not occurred (Jacobsen and Parker Citation2016).

Fossil fuel extraction may provide short-term boosts to the local economy, but it is not a formula for long-term prosperity.

Struggling communities may be willing accept slow long-term growth tomorrow in exchange for an economic boom today. However, it is worth noting that many economic studies on this topic focus on topline economic figures while largely ignoring the distribution of costs and benefits across socioeconomic identities due to fossil fuel extraction (Schafft, Brasier, and Hesse Citation2019). This stands in sharp contrast to accounts produced by sociologists and others, which show that commodity booms often exacerbate existing social inequalities (Fernando and Cooley Citation2016; Griswold Citation2018; Jerolmack Citation2021; Malin, Ryder, and Lyra Citation2019), even driving low-income residents into homelessness (Schafft et al. Citation2018).

… Oil and gas production does little to reverse “human capital flight” from rural counties, suggesting that the fracking boom has not improved these counties’ long-term prospects (Mayer, Malin, et al. Citation2018).

Oil and gas production may also undermine the agricultural sector in these communities (Malin and DeMaster Citation2016), weakening their resilience after the boom turns to bust.

Historical treatments of fossil fuel production in the United States also emphasize that the majority of the value created by fossil fuel production flows to non-local owners and investors, often leaving producer communities poor relative to the rest of the country (Gaventa Citation1982; Stoll Citation2017). Stoll (Citation2017) describes how the coal industry followed a logic of enclosure, essentially proletarianizing Appalachia’s peasant class by making it impossible for Appalachians to remain as independent smallholders who could live off hunting, foraging, and farming in the region’s food rich hollows. Coal mining may have been a high wage occupation for decades, but the influx of external capital into Central Appalachia is nonetheless why so many of its residents became wage laborers in the first place. Now, as mechanization and the energy transition cause coal production in Appalachia to plummet, the region lags the rest of the United States in the majority of indicators of health and human development (Housing Assistance Council Citation2020).

The Distributional Consequences of Commodity Booms

For all of the disagreement in the literature, most research does conclude that unconventional oil and gas production tends to create high-wage jobs in the communities that host expanded production (Munasib and Rickman Citation2015; Weber Citation2012). But demand for field workers notoriously outstrips the ability of local communities to supply labor, meaning that boom communities experience rapid population growth. Which existing residents gain and which residents lose from this influx of highly paid workers?

The harms and benefits created by oil booms are distributed unequally across regions, localities, and socioeconomic identities (Schafft, Brasier, and Hesse Citation2019). Regionally, residents of communities on the periphery of oil booms see themselves as living in a “Goldilocks Zone”: They are close enough to benefit from economic spillover, but far off enough to avoid social and environmental harms (Junod et al. Citation2018). Within a locality, there is an important spatial element to whether landowners benefit on net from oil production. Unlike renters, landowners stand to reap large monetary rewards if geological chance is in their favor: Oil companies may purchase mineral rights or offer large leasing fees to those whose land they need.

One study of property values in fracking communities found that homes closest to well pads tend to lose value if the fracking rig is visible from the home or if the home relies on groundwater (and thus its drinking water may become polluted).

However, homes a little further from wells see a small positive effect on home values due to leasing fees, especially after the initial drilling has been completed. The sweet spot here is to be close enough to benefit from lease payments but far enough to be unbothered by light, noise, and water pollution (Muehlenbachs, Spiller, and Timmins Citation2015).

In sharp contrast to landowners, almost all renters are positioned to lose from the arrival of the oil and gas industry. So many non-local workers are drawn to boomtowns that even the proliferation of temporary workforce housing establishments (informally known as “man camps”) cannot meet demand for housing. (Caraher et al. Citation2017). One econometric working paper finds a small but significant increase in mean rents in Pennsylvania’s fracking-friendly Marcellus counties as opposed to those of New York, where fracking was banned (Muehlenbachs et al. Citation2015; see also Williamson and Kolb Citation2011). While the median effect size is small, they estimate fracking to have caused a $250/month rent increase in around ten percent of in-sample census tracts.

Qualitative accounts of housing markets in boomtowns, however, document much more severe increases in rent. As early into the boom as 2010, locals reported that motels had no vacancies and some two-bedroom apartments had seen monthly rents triple to $1,000 (Lindholm Citation2010). A field hand in Williston reported being fortunate to pay “$450 a month for a mattress on the floor of a living room, which I shared with four other migrant men in a small townhouse packed with as many as 12 people” (Smith Citation2021). The North Dakota Man Camp Project documents over fifty man camps in the Bakken oil patch (Caraher et al. Citation2017). These man camps range in quality and formality, from prefabricated barracks in company towns to illegal encampments of RVs. However, demand for RVs and mobile homes in formalized man camps is so high that rents can hit $2,000 a month (Caraher et al. Citation2017, 270).![]() Similar greed-fed insanity in bitumen capital, Ft Mac, Alberta

Similar greed-fed insanity in bitumen capital, Ft Mac, Alberta![]()

Rising rents are documented in other fossil fuel production communities. A journalist documented rents rising by 12 percent a month in Southwestern Pennsylvania due to the arrival of migrant workers coming to work the Marcellus shale (Griswold Citation2018, 154). Meanwhile in northern Pennsylvania, a resident reported being unable to find housing because landlords “only rent to the gas company because they can charge per head… [They] shove five or six guys into [an apartment] and charge $300 a head… They don’t like to rent to families” (Schafft et al. Citation2018, 521). Across the country in South Texas, a city council member and his family were evicted from their long-time home, where they had paid $550 a month. The landlord then put the home back on the market at the rate of $125 per man per week, with a sign out front reading “Oil Field Guys—Welder—Pipe Liners (Guys Only).” The landlord said the home could hold up to 12 men (MacCormack Citation2011).

Inflation in these areas is not limited to rents. Any increase in the cost of living can put stress on people on fixed income such as retirees, people on disability or those receiving other kinds of government benefits (Ryser and Halseth Citation2011; Schafft et al. Citation2018). If local wages cannot keep up with rising costs of living, then very few existing residents stand to benefit from a commodity boom. Economists argue that “backward linkages” from the fossil fuel sector to other sectors of the local economy are the largest source of positive welfare for existing residents of fossil fuel communities, but they also note that this effect is generally small and “is conditioned on the policies of resource projects as well as the availability of local markets for goods and services” (Cust and Poelhekke Citation2015, emphasis mine). For example, fast food workers in Williston command considerably higher wages than they do elsewhere, but the price of fast food is similarly inflated (Little Citation2014).

Indeed, even oilfield workers report that the high cost of living can prevent them from accumulating significant savings despite high oilfield wages (Smith Citation2021).

Goods in rural boom areas are prone to inflation because their relative isolation makes it difficult to increase the supply. Housing costs are especially vulnerable to boom-induced inflation. First, the housing supply is notably inelastic, especially in smaller, isolated communities that are unable to support a dedicated construction industry. Construction costs in these communities start high, and they only increase as the price of labor and land go up in response to the local boom economy. On top of these costs, developers may be hesitant to invest in new construction when it is unclear what the real estate market will look like after the bust, when incomes fall and outmigration begins (Fernando and Cooley Citation2016, 426). While temporary workforce housing would provide a relief valve for some of this excess demand, man camps are often prohibited by local ordinances due to their unsavory reputations ![]() notably drugs, and workers raping local women and kids

notably drugs, and workers raping local women and kids![]() (Caraher et al. Citation2017).

(Caraher et al. Citation2017).

For all of these reasons, the rental housing supply cannot keep up with demand generated by waves of incoming oilfield workers, whose presence is attested to in part by the volume of oil produced in the county.

H1: Increased Oil Production Will Lead to Increased Eviction Counts in Williams County, N.D

Furthermore, we expect that the rise in market rents is responsible for the linkage between oil production and eviction rates, although some of the rise may be attributable to (for example) an increase in lease violations associated with the influx of young, male oilfield workers.Footnote1 As rents skyrocket in Williams County, where renters enjoy few renter protections, we predict that evictions will rise apace.

H2: The Effect of Increased Oil Production on Eviction Counts is Mediated by Median Rent and the Size of the Local Renter Population

Finally, we expect these evictions to primarily affect longer-term residents. Because migrants to the town generally work in the oil fields and receive the highest salaries, dislocation is expected to be highest among existing residents, who are the most likely to rely on fixed incomes (Ryser and Halseth Citation2011) or earn wages from non-fracking occupations. While “backward linkages” (Cust and Poelhekke Citation2015) from the fossil fuel sector to other sectors exist (Little Citation2014), they will be too weak to counteract the rising cost of living.

H3: Evictions Increased among Residents with Residential Histories in Williston, N.D

We now turn to the data we will use to evaluate the effects of the fracking boom on housing instability in Williams County and Williston, North Dakota.

…

Results

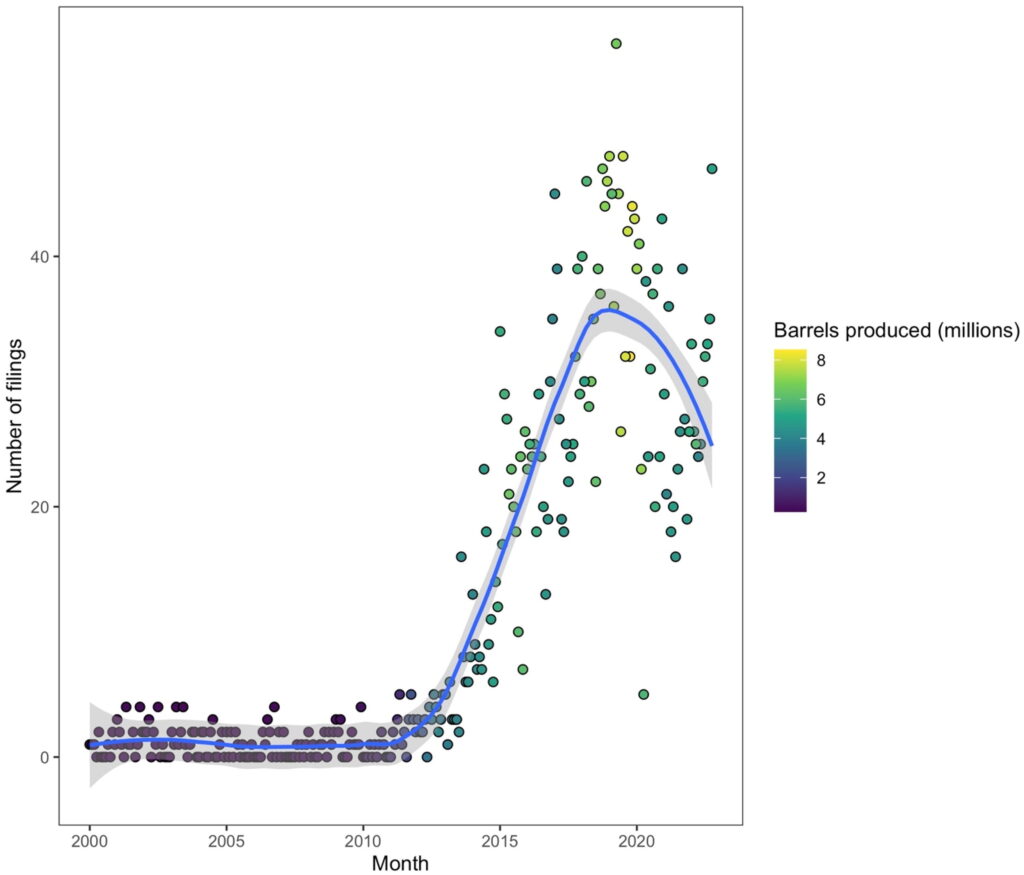

In , we plot eviction filing counts in Williams County by month. The color of points indicates the number of barrels of oil produced in Williams County. shows a clear association between the rise of oil production and eviction filings in Williams County. Landlords filed evictions at a stable rate of 1–2 a month from 2000 to 2010, before filings began to climb steadily to an average of 21 a month by 2015 and 42 a month by 2019. Over this same period, oil production in Williams County climbed from 300,000 barrels a month in 2000 to over 5.9 million barrels a month in 2015 and 7.5 million barrels a month in 2019. As

shows, Williston’s eviction rate began to climb at the same time as Williams County’s oil production.

Figure 1. Monthly evictions in Williams County increased dramatically with oil production.

Both evictions and oil production peaked in 2019, because the COVID-19 pandemic decreased demand for oil products at the same time as an aggressive federal response prevented millions of evictions nationwide.

…

Discussion

The above findings demonstrate that boomtowns like Williston, N.D. experience severe housing stress. Furthermore, the people most likely to suffer from housing instability are those residents whose incomes did not keep pace with the rising cost of living. How generalizable are these findings? We selected Williston because it is a boomtown for which we were able to find high quality timeseries for evictions data. While qualitative accounts of other rural fracking communities suggest that they also experience elevated eviction rates, the data do not exist for us to study this relationship quantitatively.

…

Tenant protections can have profound effects on eviction filing rates (Nelson et al. Citation2021; Sabbeth Citation2022). North Dakotans could particularly benefit from simply increasing the time that a landlord must wait between first notifying tenants of intent to evict and actually filing that eviction, a reform that has been shown to substantially reduce filing rates (Gromis et al. Citation2022). Tenant protections are even more potent when reinforced by programs that give tenants formal representation in courts (Engler Citation2010; Sandefur Citation2015; Seron et al. Citation2001) or which give tenants more information about their rights (Golio et al. Citation2022). However, creating the kind of social service infrastructure necessary for tenants to defend their rights takes concerted effort: Nonprofit expenditures lag in many rural areas (Shapiro Citation2021) and tenant-oriented groups are especially sparse in towns like Williston that previously experienced little housing insecurity (Kneebone and Underriner Citation2022).

Tenant protections are necessary but insufficient to keep eviction filings rare. Small towns and rural areas can improve local housing stability not just by making it easier to build housing, but by making it easier to build affordable housing. The negative effects of exclusionary zoning on the housing supply are often thought of as a suburban problem, but even small towns and rural areas make it hard to build manufactured housing, which is the largest private source of affordable housing in much of the country (Sullivan Citation2018).

Many communities on the Bakken have passed ordinances meant to block the establishment of man camps (Caraher et al. Citation2017), which diverts worker demand for housing into local rental markets instead.

Small towns must also be willing to fund and site subsidized housing, which is among the most effective means of ensuring housing stability (Preston and Reina Citation2021). For renters who already have a home or are unable to find a spot in subsidized housing, direct financial support is an effective shield from displacement (Aiken et al. Citation2022; Hepburn et al. Citation2021). However, housing is so expensive in Williston that the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program is ineffective. The Housing Authority of the City of Williston is authorized to lease only 110 units through HCVs, but the Authority’s budget turns out to be the greater constraint. Due to the high cost of housing, the Authority runs up against its budgetary capacity once 50% of those vouchers are in use (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Citation2023).

Subsidized housing and direct housing support are expensive, but governments can fund them by capturing the profits of extractive industry through means like severance taxes. Notably, Pennsylvania (at the heart of the eastern fracking boom) does not collect severance taxes, and so does nothing to make residents whole who experience the harms of fracking. While a lucky few Pennsylvanians become “shaleonaires,” many more suffer harms from fracking without any compensatory gains. ![]() This unuust unfairness is used to great advantage by frac’ers to divide and conquer communities they invade.

This unuust unfairness is used to great advantage by frac’ers to divide and conquer communities they invade.![]() Communities must negotiate rental support for low- and fixed-income renters in order to ensure the community as a whole benefits from its mineral resources.

Communities must negotiate rental support for low- and fixed-income renters in order to ensure the community as a whole benefits from its mineral resources.![]() Which frac’ers make sure never happens.

Which frac’ers make sure never happens.![]()

Conclusion

The fracking boom may be winding down![]() or are frac’d wells played out because of industry’s greed? Refer below to Art Berman’s post for details

or are frac’d wells played out because of industry’s greed? Refer below to Art Berman’s post for details![]() , but unconventional oil and gas extraction is likely to continue for decades. At the same time, new boomtowns may arise where minerals necessary for the energy transition are located. The Biden administration’s use of industrial policy to onshore supply chains will have dramatic effects on the geography of jobs in this country. Tiny communities adjacent to rare earth metals, such as those in the desert on the California-Nevada border, may experience housing dynamics similar to those that have occurred in Williston. Meanwhile, mining companies are preparing to dramatically expand copper and lithium production, sometimes in conjunction with geothermal drilling projects that use hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques similar to those used in unconventional oil and gas extraction.

, but unconventional oil and gas extraction is likely to continue for decades. At the same time, new boomtowns may arise where minerals necessary for the energy transition are located. The Biden administration’s use of industrial policy to onshore supply chains will have dramatic effects on the geography of jobs in this country. Tiny communities adjacent to rare earth metals, such as those in the desert on the California-Nevada border, may experience housing dynamics similar to those that have occurred in Williston. Meanwhile, mining companies are preparing to dramatically expand copper and lithium production, sometimes in conjunction with geothermal drilling projects that use hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques similar to those used in unconventional oil and gas extraction.![]() In Canada too

In Canada too![]() Even towns aiming to transition from coal to nuclear may experience acute housing pressures (Bleizeffer Citation2022). These industries will be vital to the decarbonization of the economy, and so it is imperative that resource extraction be able to proceed in as just and equitable manner as possible (Malin, Ryder, and Lyra Citation2019).

Even towns aiming to transition from coal to nuclear may experience acute housing pressures (Bleizeffer Citation2022). These industries will be vital to the decarbonization of the economy, and so it is imperative that resource extraction be able to proceed in as just and equitable manner as possible (Malin, Ryder, and Lyra Citation2019).

The lesson from the fracking boom is clear: Rural towns that welcome extractive industries must adopt tenant protections that are more commonly associated with big cities. Rural towns should also seek to redirect some amount of profits from resource extraction to budgeting for rental support and other housing subsidies.

However, as scholars like Malin and DeMaster (Citation2016) and Jerolmack (Citation2021) detail in their studies of oil producing regions in Pennsylvania, communities are at a structural disadvantage vis-à-vis large corporations when it comes to negotiating the terms of extraction. Individuals deciding whether to allow fracking on their land can easily choose to forego direct benefits by blocking drilling on their property, yet as individuals they have no ability to avoid the negative externalities of extractive activity in their community. Unable to control the decisions of their neighbors, residents of these communities are inclined to grant corporate agents access to their land (Malin Citation2014). Policymakers and residents of new boomtowns should take care to negotiate community benefits before land agents come and before the exact geographic distribution of harms and benefits is made clear.

Communities will only benefit as a whole from resource extraction if they can negotiate as if they were behind a Rawlsian veil of ignorance.

These findings also highlight something of a paradox: Where is the best place to situate extractive industries? From a strict fiscal perspective, populated areas are ideal. While most localities that engaged in fracking report that revenues exceed costs, “local governments in highly rural regions experiencing large-scale growth have faced the greatest challenges” (Newell and Raimi Citation2018). Populated areas have the lowest transportation costs, more elastic housing supplies, better infrastructure, and thus a greater ability overall to use revenues to adjust to changing economic conditions.

But of course, extractive activities in populated areas create graver environmental justice concerns: there are simply more people who will be exposed to pollution and who may see their properties permanently scarred.

Above photos of some of the frac invaded and poisoned in NEBC, Canada

Resource extraction creates tradeoffs between the higher environmental costs of operating in populated areas and the higher economic costs of operating in isolated areas. This tradeoff cannot be eliminated, but its impacts can be planned for and attenuated by local policymakers. If we have to extract resources in populated areas, extra care should ![]() But never is because the rich and their industries always win and groundwater, environment and public health always loses

But never is because the rich and their industries always win and groundwater, environment and public health always loses![]() be given to environmental protections. If we have to extract resources in isolated areas, local policymakers need to plan for tenant protections, housing supply, and rental support before the population boom arrives.

be given to environmental protections. If we have to extract resources in isolated areas, local policymakers need to plan for tenant protections, housing supply, and rental support before the population boom arrives. ![]() But never do

But never do![]() Given the demand for resources that will accompany the energy transition, the number of both kinds of sites will likely grow in the future.

Given the demand for resources that will accompany the energy transition, the number of both kinds of sites will likely grow in the future.

…

Refer also to:

2024: Art Berman: Beginning of the End for the Permian (and Bakken and Eagle Ford …)

2015: Thank Fracking: Business licence for Fox Creek hotel goes up 133,233 per cent