Pick up Andrew Nikiforuk’s Saboteurs for a real read into Gwyn Morgan’s “integrity.”

Winner of the 2002 Arthur Ellis Award for Best True Crime

Winner of the W.O. Mitchell City of Calgary Book Prize

Finalist for the 2002 Governor General’s Literary Award for Nonfiction

Finalist for the Wilfred Eggleston Award for Nonfiction

Many more details into Mr. Morgan’s lack of integrity here:

Calgarians named to Order of Canada by Sarah McGinnis, Calgary Herald; With Files From Postmedia News, December 31, 2010

The man behind the creation of Encana and a prominent Calgary poet are among the latest to be named to the prestigious Order of Canada.

Retired Encana CEO Gwyn Morgan and poet Christopher Wiseman are among 54 new appointments to the Order of Canada announced by Gov. Gen. David Johnston on Thursday.

Morgan spearheaded the merger between Alberta Energy and Pan-Canadian Energy which led to the creation of Encana Corporation, a move which has been heralded as the most significant transaction in the history of Canada’s energy sector.

The internationally known business man also saw the natural gas potential of northeastern B.C. before most of his competitors.

Morgan is being recognized as a member of the Order of Canada for his contributions as a business and community leader as well as his philanthropy.

“It’s something very special and something I am very humbled to have, and I am very appreciative,” Morgan told the Herald.

Wiseman has also been named as a member of the Order of Canada for his contributions to the development of creative writing as both a poet and a professor.

Wiseman has published several collections of his poetry, including most recently 36 Cornelian Avenue, which revisits his childhood growing up in Scarborough, England during the Second World War.

He has been a driving force in this province’s literary scene, establishing the creating writing program at the University of Calgary where he taught from 1969 to 1997.

Morgan and Wiseman will be invested at a ceremony sometime next year.

Poet, novelist and publisher Nicole Brossard of Montreal has been named an Officer of the Order of Canada.

Brossard has published more than 30 books including These Our Mothers and Mauve Desert.

She is joined as an Officer by broadcaster Shelagh Rogers from Vancouver, who is honoured for her contributions as a promoter of Canadian culture. Rogers is best known for her work on CBC’s current affairs programs including Morningside and This Morning.

The Order of Canada was established in 1967 by Queen Elizabeth and is regarded as the centrepiece of Canada’s honour system. **Honouring Canada’s rape & pillage status quo protectors?**

“The Order recognizes people in all sectors of Canadian society. Their contributions are varied, yet they have all enriched the lives of others and made a difference to this country,” the Governor General’s release said.

http://www2.canada.com/calgaryherald/news/city/story.html?id=305080fb-e5c4-4e91-9028-510ac9fd60de

Gwyn Morgan – a road to the Order of Canada, When it was announced at the end of December that Gwyn Morgan had been named to the Order of Canada in recognition of his lifetime of work in the Canadian oil and gas industry, it came as no surprise to his longtime friend, Dick Wilson by James Waterman, Mar 11, 2011, Alaska Highway News

When it was announced at the end of December that Gwyn Morgan had been named to the Order of Canada in recognition of his lifetime of work in the Canadian oil and gas industry, it came as no surprise to his longtime friend, Dick Wilson.

“I nominated him,” Wilson said with a laugh. “It’s something that I felt was long overdue.”

Wilson has known Morgan for twenty-four years, ever since Morgan was the Senior Vice President in charge of oil and gas at Alberta Energy, and Wilson had to sit himself down in front of his desk for a “very intimidating” interview. Wilson got the job, eventually becoming the Vice President of Public Affairs at Encana after Morgan led the merger between Alberta Energy and PanCanadian Energy in 2002, consequently creating the Canadian petroleum giant.

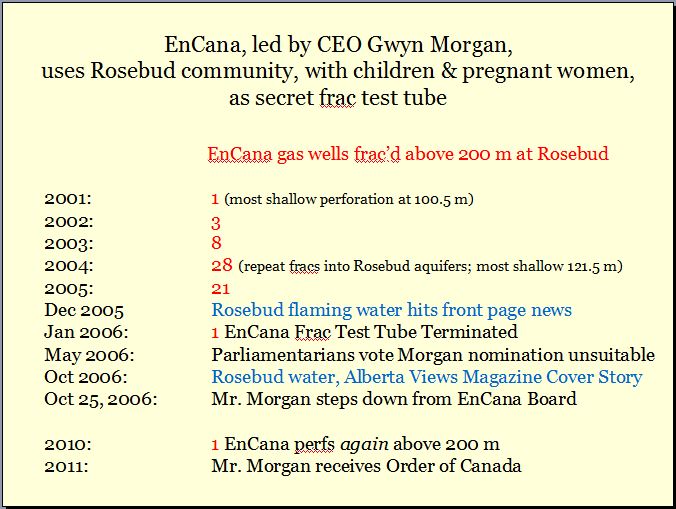

Wilson describes his old friend and colleague using words and phrases like “loyal” and “highly professional” and “extremely ethical.” As he tells anecdotes that attempt to describe Morgan’s character as a businessman, as a philanthropist, and as a champion of the oil and gas industry in Canada, the word that pops up again and again is integrity. **Integrity required to lead a company breaking the law, frac’ing community drinking water supplies in Rosebud Alberta and Pavillion Wyoming? Some integrity!**

It seems that Morgan was born to personify that trait.

The story of his journey toward membership in the Order of Canada began just as so many of these stories do, as the tale of a child from a humble and hardworking Canadian family.

“I was raised on a farm west of a little town called Carstairs, which is northwest of Calgary, just on the edge of the foothills,” said Morgan. “Like a lot of little towns, it was on the rail line between Calgary and Edmonton. And it was a typical little prairie town with the grain elevators. Virtually all of the shops and services that we used were right in the little main street.”

“We worked hard,” he continued. “We had lots of challenges with crop failures and things. But I never could have imagined having better roots. I mean, you learn resiliency. You learn effort. Responsibility. And I had great parents. That was my upbringing.”

“At the very foundation of who I am were the value systems that my parents passed on to me. Integrity. And always being truthful. A sense of morality. All those things. Those are grassroots fundamentals that I’ve always believed you never compromise no matter what. And so if I have a reputation that I treasure most in business and in general, it would be a sense of strong integrity and a sense of fairness that they passed on to me. And through my whole career, fortunately, I never compromised. And it was also, interestingly enough, maybe one of the very leading reasons why the company was successful.”

“Good people want to know that the leadership you have can be trusted and they really care and they’re not just in it for themselves,” Morgan explained. “Those are things that I learned early. And maybe were in some ways the key to what happened later.”

His parents not only taught him the value of hard work and integrity, but his father also happened to gently push him toward his career, which was inevitably a push in the right direction. Morgan only required that gentle push because all he knew early in his university career was that he was a good math and science student. He was not yet certain of a vocation that would allow him to take advantage of his talents until his father suggested engineering.

“And he only knew engineering because he had a little road-building business on the side. And he met some engineers and thought it was a pretty good job,” Morgan said, chuckling. “That was what got me into engineering.”

Morgan laughs when he thinks about his move into engineering, partly because he feels that so many children only dream of taking up the professions that they know, such as doctors or teachers, and so few seem to know the duties of an engineer.

“They should know what engineers do because virtually everything in the world is engineered,” he said. “We’re in the most technological age ever and there isn’t anything in terms of where we live, how we live, where we drive, what we drive, how we fly, how we communicate that isn’t engineered.”

“And they all say, ‘What does an engineer do?'” he adds, chuckling again. “So, there isn’t any more broad and exciting field, but there’s not a TV program about it.”

After completing his engineering degree at the University of Alberta, Morgan took his first step into the oil and gas business. He recalls that at that time all of the Canadian-owned companies were small independents struggling to compete with major companies that had their headquarters beyond our borders. Most of the jobs in his field were with those big foreign-owned operations and so he naturally gravitated towards those opportunities, even though he was eager to help Canada really make its mark in the sector.

“When we had the opportunity to start Alberta Energy Company in 1975,” he said, “my big motivation was that I could be somewhere where we could make decisions at home.”

Morgan was twenty-nine years old, just eight years out of university, a period during which he had always had to report to a head office in the United States as part of his first company job in the industry.

“I was really excited about a Canadian company that would be owned by Canadians,” he said of the creation of Alberta Energy.

Alberta Energy began as a resource company with its hand in a range of areas including petroleum products, pipelining, fertilizer plants and forest products. Morgan was the first man in the fledgling organization’s oil and gas group.

“In April of 1976,” he began, “we were all set and had everything organized and we started a drilling program. A natural gas drilling program. And one of my great memories was we had what we call a spud-in ceremony of the very first well to be drilled by the company. And I had this enormous Canadian flag flying in the wind from the top of this rig.”

“And I just remember sitting there and watching that flag and saying, ‘You know, this is not only the beginning of what we hope will be a successful company, but also symbolic of my own passion about Canadians doing something on their own.'”

It is just one example of a level of patriotism that Wilson characterizes as a “fierce pride in the country.”

“Not just in the country,” he added, “but in the country’s ability and potential. Each region has something different to contribute to the economy, to the social atmosphere, to the culture of the country.”

That is Morgan’s philosophy.

His pride in Canada and its energy sector eventually led him to tackle one of its newest institutions in the early 1980s: the National Energy Program (NEP).

“The National Energy Program goes back to the days of [former Prime Minister] Pierre Trudeau and [former Minister of Finance and Minster of Energy, Mines and Resources] Marc Lalonde, where they were basically out to tax the oil and gas industry in western Canada,” said Wilson. “And it devastated – it devastated – the oil and gas industry to the point of – I don’t know whether it was forty or sixty billion – billion with a b – dollars.”

“Gwyn was at that time the president of the Independent Petroleum Association of Canada, which is now the Canadian Petroleum Association,” Wilson continued. “And he was diligent in efforts to team up with others and dismantle the NEP when the Conservatives came into power.” **A dreadful failure by Morgan et al. Canada would be a much more resilient country, with the NEP.**

Now the oil and gas business in Canada is experiencing an entirely different set of circumstances. It is among the leading industries in the country and provincial governments – particularly in the resource hotbeds of British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan – are striving toward streamlining the regulatory processes and instituting favourable fiscal regimes to promote investment and development. **Translation: Massive deregulation to enable the frac’ing free for all, rape and pillage of communities, lands, aquifers, farms, families, truth, justice and more.**

Wilson feels that Morgan has played a significant role in that change.

“He has been instrumental in, shall we say, helping government better understand the industry,” said Wilson. “Gwyn is never one to shy away from offering an opinion when it’s warranted. I wouldn’t say he’s opinionated, but if he has an issue and he believes strongly about it, he will enunciate it.”

Morgan certainly is not shy about his opinion of the value of the industry.

“I think that one of the things that I tried to do when I was involved in the industry was to help people understand, first of all, how important it is to the country,” he said. “And, second of all, that providing energy for people is a necessary and absolutely noble endeavor. And I think too often in the industry we spend time apologizing for being the oil and gas business. Or companies think, ‘Well, I’m going to go buy five windmills and I’ll talk about the windmills and not the oil and gas.'”

“What I always tried to do was have our people understand that they’re working for a great company, they’re working for a company that they can trust, has a social and environmental responsibility ethic, and in an industry that is providing a very important, crucial service to people. And I think that leaders in industry need to say that more often.”

“I’ve operated and seen operations throughout the world,” he continued, “and I’ll compare our oil sands with what’s going on in the Niger Delta or in government companies in Ecuador any day.”

Morgan eventually became CEO of Alberta Energy, assuming the role vacated by the company’s founder, Dave Mitchell. Mitchell has also been named to the Order of Canada in recognition of his contribution to Canadian life, a fact that makes the honour “even more special” for Morgan.

“Dave and I connected on several different levels,” said Morgan, describing his predecessor as a good and trustworthy man who shared the values that Morgan had inherited from his parents.

However, the duo had their differences as well.

“Dave grew up in a different age,” he continued, “and he had a different perspective on things in terms of where the world was going. He believed the company should be diversified. And I ended up focusing it. But that was also because that was the changing times. At the time when we started Alberta Energy, there was this widespread thought that you shouldn’t just be in one business, like in oil and gas. You should be in a number of businesses.”

Alberta Energy was not as diversified as other companies at the time, preferring to solely concentrate on natural resources, but Morgan was still eager to narrow the focus even further.

“His era was diversification,” Morgan explained. “And it was what everybody thought was right. What I guess I learned from that was that it’s very hard to be really good at a whole bunch of different things, because you lose your focus. Every business is so difficult and so competitive that you better really focus. And when we really focused the company, we grew best.”

Morgan really began to show the strength of an organization with a sharper focus in 2002 when the merger of Alberta Energy and PanCanadian Energy finally created Encana. Not only had he divested the company of its other businesses, but he had also gone from “being the guy that drilled the first well” for Alberta Energy to the man who had built that upstart oil and gas division into an outfit that was big and strong enough to rival any of the largest energy companies in the world.

It was also a moment when his unique leadership skills truly shone.

“A merger of that magnitude – two large companies – is something that gives angst to just about everybody in terms of where are they in the overall picture,” said Wilson. “And he quickly recognized that. So, he issued emails, and I would say virtually daily. I mean, there may have been one or two days when he [was] out, like down in New York with the analysts and things like that. But he would report back on those meetings as soon as he got back. And the funny thing was we still had – because the merger had not been completed legally – we still had to run two companies, right? And so there were two different IT systems. And so everything had to be replicated so that his message went out to all employees at the same time. I mean, he was that sensitive to it.”

It was just one aspect of an overall approach to leadership that Morgan had developed working with Mitchell early in his career with Alberta Energy.

“As a leader, he had a way of giving you responsibility,” said Morgan, discussing the management style of his former mentor. “And it wasn’t very often that Dave would say, ‘You got to do this or you got to do that.’ He would give you advice. He’d have you think about it. But most of the time you knew it was your show and your responsibility. And I learned that from Dave. Because that’s a great, empowering thing.”

Wilson has similar memories of Morgan from when he was hired to join the public affairs department at Alberta Energy.

“He said to me at the time, ‘I don’t like surprises. So, keep me posted. But you’re running the public affairs. Not me.'”

“He recognizes the skills and talents of people,” Wilson continued. “But, more importantly, he allows you to do your job without hovering. He expected you to do your job without hovering.”

According to Wilson, even if Morgan did not expect his staff to always need his input, he did expect his staff to offer their opinion. He recalls a specific occasion when they were producing the annual report. Facing a time crunch and plagued by an inability to make a choice on their own, Wilson and his team decided to let Morgan pick the design. The CEO subsequently chose the one that Wilson had at the bottom of his list. Wilson did not say a word until the report had already been published, and both of the men were sitting together at a fundraising dinner, thankful that the task was finished. Asked why he had not spoken up earlier, Wilson only remarked that he simply felt that it was his job to produce the report that Morgan had chosen.

“He said, ‘Don’t you ever do that again,'” said Wilson. “He said, ‘I didn’t hire you to be a yes-man. I hired you because I value your opinion. I might not have to agree with your opinion, but I value it. You did a disservice to me and you did a disservice to yourself.’ And he said, ‘Don’t ever do that again.’ And he said, ‘Now pass the bread.'”

“But that’s the way the guy was in his leadership,” Wilson continued. “He said what he thought and that’s it. It’s done.”

“When he did the corporate constitution, he wrote it, drafted it, and then sent it to me,” he said, remembering another example of Morgan’s strength as a leader. “And I’d edit it and send it back. And he’d send the next one. And it’s a little longer than the first one. And so when he finally was comfortable with it, what he did is he had his assistant contact different employees at random and invited them to come to a meeting with Gwyn ten days hence. Didn’t say why. Met with them and had them read the constitution – the draft – and then give their spontaneous reaction to it. And that gave him a glimpse of a cross-section of the employees. And I don’t know how many of those he did, but that was also his way of getting right to the audience in terms of the development of the message. It went through many, many more iterations, but then we had a significant launch of a corporate constitution, because that told employees: this is important. Never mind policy manuals that get thrown in desks and all the rest of it. This is what guides you. Period.”

“It was the only employee-corporate constitution that we know of in Canada,” Wilson concluded.

It was also evidence of a management style that Wilson claims was not strictly “top down.”

“In many respects, when the president had to make a decision, he made the decisions,” he explained. “Period. But in other respects: no. Because, again, he recognized the value of inclusion in terms of keeping employees informed and consulted when it affected them.”

Consequently, when Morgan did have to make an executive decision, it was a decision that reflected the sentiments of his employees as well, because they were all on the same page. Wilson insists that Morgan’s attitude and philosophy in that manner created a great culture and a “phenomenal” environment in which to work.

“I had the best PR job in the province of Alberta,” said Wilson. “Because of him and because of his predecessor Dave Mitchell.”

Indeed, Mitchell’s influence is quite visible in Morgan’s work as a leader in business, but also as a leader in philanthropy.

“The one thing maybe I learned from Dave more than anything else,” said Morgan, “is that no matter what one of your people who reports to you is doing, what the job is, what the project is, it’s not just getting the project done well. Or getting the particular activity done well. It’s how do you make it so that that person learns the most from it. Always looking at how to develop. He never stopped thinking about how to develop his people. And I benefited from that greatly.”

Morgan has taken this lesson beyond developing the skills and talents of the people in his company to building the capacity of organizations and communities to which he and Encana have donated their philanthropic dollars.

“We supported virtually every community we operated in, and every community in every country we operated in, and we tried to make a difference in that regard,” said Morgan, noting that Alberta Energy was one of the first members of the Imagine Canada program through which corporations commit to donating one percent of their pre-tax revenue to charity. “But the one fundamental premise that I believed in and which we used in our evaluation of donations and sponsorships was capacity building. We didn’t believe in just giving money away. Just giving money away can in some ways just make people dependent. But if it can help them build capacity, in a learning sense or in some other sense, that was our big measure.”

“And that’s why a lot of our own personal donations focus on education,” he continued, discussing the foundation that he and his wife established after his retirement. “And not just sort of generally giving away to public education, but more in the sense of actually helping people – students – who have great potential, but otherwise couldn’t get there. That makes it harder work, because you have a lot more selection to do. And we do believe that building capacity, whether it be in education or other ways, is the best way you can use philanthropic dollars.”

That is the reason why Encana was so heavily involved in developing and funding oil and gas industry training programs at Northern Lights College, as well as contributing to constructing the Industry Training Centre at the school’s Fort St. John campus. As an early and dominant player in the region, Encana recognized that there were problems stemming from the seasonality of work in boggy areas of muskeg, the lack of industry employment opportunities for residents of the region, and the absence of training programs that would allow locals to join the oil and gas workforce. The programs at Northern Lights College were designed to help address those issues. Morgan attended the official launch of those programs and he was met with praise from the community for Encana’s commitment to promoting year-round industry activity and hiring locally in the region.

“I think the Northern Lights College thing is one of the best things we did,” he said, remembering the warm reception.

Now Morgan is living what he likes to call “Chapter Three” of his life.

“After all those years in the energy business and building a company,” he said, “I wanted to make a complete change. We also made a change in where we live, because we’ve always loved the west coast. And so I made a specific decision not to involve myself anymore in energy.”

That is not to say that he is no longer involved in business, however. Since his retirement from the oil and gas industry, he accepted an invitation to join the board of HSBC, the largest bank in the world, which has its headquarters in London, England. He is the first person from the Americas to assume that position. He is also on the board of one of the biggest engineering companies, SNC-Lavalin.

“I always considered myself sort of a citizen of the world and this is the time for me to be involved even more in that,” he explained.

Morgan describes the honour of joining the Order of Canada as a “wonderful thing.”

“When you live in a country that we’re as fortunate as we are to live in, and you love it as much as I do,” he added, further discussing the recognition, “it’s a very special thing.”

It is also the culmination of a career that Morgan does not speak of in terms of past achievements, but in terms of lessons learned along the way.

“Over the years,” he said, “what was probably most satisfying about my career was that I learned how important it was to build an esprit de corps – a team, a group of people, and a whole company that were passionate about what they did. And that were absolutely proud of the organization they were working for and the leadership that they had.”

Through his experiences with Alberta Energy and Encana, he became a firm believer in the value of learning from mistakes and the power of the innovative creativity of people when they are given the right environment in which to exercise their talents.

Still, he always returns to integrity.

“The source of most dysfunction in the world is misalignment of values and goals and rewards,” said Morgan.

“If you don’t have the value system that guides them – it’s the moral compass – and if they’re not led in such a way that what they’re rewarded for is what you want to happen, then you’ll fail. And that’s why in most countries and in many businesses and in many walks of life, including government, there is a lot of failure.”

Wilson feels it is important that Canadian businessmen of Morgan’s stature are receiving this kind of recognition from their country.

“A lot of the average Canadians do not know their business icons,” he lamented.

“There are people who would go to the end for the world for Gwyn Morgan,” he continued. “I’m one of them. I know many, many people, in the company and outside of the company, that have the deepest of respect for him. He’s probably got his detractors as well, I’m sure. But from my perspective, he’s a very unique dude.”

**

Refer also to: