The recent Supreme Court ruling on Jessica Ernst in her case against the Alberta Energy Regulator demonstrates once again that Canada’s myopic legal system can easily lose sight of justice.

The matter is not as complicated as the legal jargon that surrounds the ruling like some overgrown bush.

Once you prune away the mumbo jumbo (the legal system has yet to adopt English as its preferred language), the Supreme Court of Canada decided that a statutory immunity clause protected an allegedly abusive regulator from a Charter claim.

As a result, any quasi-judicial regulator in the country could trample any citizen armed with damaging information about its performance, and abrogate their freedom of expression. Or worse.

All they need do to get away with such democracy-killing behaviour is pull out an immunity clause that says, in essence, the Supreme Court says we’re above the law, and we can behave badly.

Writing in one of the nation’s top legal blogs, Sossin found that the Supreme Court not only missed the whole point of the case, but probably damaged the Charter of Rights and Freedoms to boot.

“In my view, the premise the Court accepts in Ernst, that a statutory immunity clause can bar a Charter claim, is flawed,” he wrote. “The availability of Charter damages… cannot be precluded by an act either of a provincial legislature or of Parliament…”

Sossin, a lawyer and political scientist, knows what he is talking about: he has worked as litigation lawyer with Borden & Elliot, served as a law clerk to the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, and is now the dean of Osgoode Law School.

He wasn’t alone. The national magazine of the Canadian Bar Association also noted that the decision had “raised a lot of eyebrows.”

But there’s much more wrong with the decision as an open public letter by Ernst herself explains.

In the split ruling, one of the Supreme Court judges, Rosalie Abella, said the regulator found Ernst a “vexatious litigant,” though no regulator in Alberta has ever described Ernst as such.

The term has dark legal implications. “It is a serious finding when a court declares a claimant to be a ‘vexatious litigant,’ resulting in the claimant being restricted or having no further access to the courts,” writes Ernst.

Alberta Chief Justice Neil Wittmann, who serves as case management judge for Ernst’s ongoing lawsuit, recently described vexatious litigants as “those who persistently exploit and abuse the processes of the court in order to achieve some improper purpose or obtain some advantage.”

Wittmann adds that vexatious litigants typically want “to punish or wear the other side down through the expense of responding to persistent, fruitless applications.”

Donald Trump, for example, has a history of behaving like “a vexatious litigant.”

But that’s not a fair description of Ernst, who had never filed a lawsuit until an alleged combination of corporate and government negligence filled her well water with explosive levels of methane.

A decade-long ordeal

But to really appreciate Sossin’s comments and the contents of Ernst’s public letter, it is necessary to review some disturbing history.

In 2007, Ernst, then still an oil patch consultant with her own thriving business, sued the Alberta government, Encana and the Alberta Energy Regulator for alleged negligence over the contamination of local aquifers during a period of intense and shallow fracking of coal seams near her home in central Alberta.

She did not take the decision lightly.

But when the government failed repeatedly to uphold the law, Ernst saw no other recourse but to exercise her civic duties.

As an ordinary citizen, she thought that she had a duty to protect groundwater, a critical public resource, from further contamination. She also thought her lawsuit might help to end the mistreatment of landowners in areas of intensive hydraulic fracturing.

Democracies fail when their citizens fail to correct the state’s injustices or those of the marketplace.

Between 2003 and 2008, more than 100 Alberta landowners lost or reported damage to their water wells as the industry “carpet bombed” farming communities highly dependent on groundwater with more than 10,000 fracked gas wells in coal seams.

Most of the impacted landowners had unpleasant or adversarial encounters with the energy regulator or the Alberta government. I know: I interviewed many of them over half a dozen years.

The regulator largely insisted that the contamination was “natural” or that landowners didn’t know how to maintain their water wells properly.

But that wasn’t the truth. The regulator, largely funded by oil and gas industry (and now chaired by a former energy lobbyist), simply allowed an industry to experiment with a brute force technology with impunity.

Energy regulators have behaved just as crudely in Australia, Pennsylvania, Wyoming, Colorado and Texas.

In Canada, only one person had the courage and financial wherewithal to sue the parties she felt responsible, and that was Ernst.

Since then, her lawsuit in the petro state of Alberta has crawled along like a prairie snail, because that’s how money and power best defeat challenges to the abuse of a state’s powers.

Alberta’s courts eventually ruled that Ernst could sue the government, which had an immunity clause against civil action, but not the regulator, which was also protected by an immunity clause passed by the legislature. Go figure out that legal contradiction.

But Ernst reckoned that the regulator had done the greatest harm to the public trust, and that immunity clauses didn’t cover breaches of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

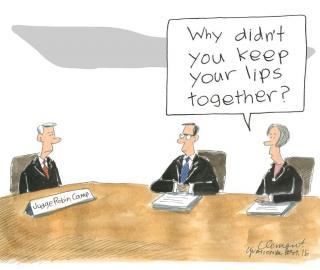

That breach was shocking: the public record shows that the regulator branded her a security threat and stopped all communication with her in 2005.

Six months later, a lawyer with the board declared during a taped interview that the organization didn’t appreciate Ernst’s public criticisms.

The board lawyer also warned Ernst, in front of a witness, that Ernst’s humiliating public discussion of the board’s actions must cease if they were ever going to address her concerns.

That’s when Ernst decided to sue the regulator. When rulings in Alberta courts prevented that from happening, she decided to take her case to the Supreme Court in 2014.

The whole higher court adventure took more than two years.

After her lawyers made their arguments in 2016, Ernst then waited an entire year for a decision that avoided the simple question at hand: can a regulatory body get away with trashing the nation’s Charter by abusing a citizen and then claim legal immunity?

In the split ruling, four judges upheld the Alberta’s court rulings and avoided the constitutionality of immunity clauses altogether.

Four judges led by McLachlin dissented and said the rights of citizens under the Charter should come first.

And one, Justice Rosalie Abella, went off on a legal tangent that supported the champions of the immunity clause.

‘Vexatious’?

In his brilliant dissection of this decision, Sossin concluded the court got most things wrong.

For starters, he wrote, “A suit for Charter damages is not the same as a suit for civil damages, and the Court’s desire to frame the former as a species of the latter (rather than as part of the spectrum of remedies for Charter beaches per se) leads the majority of the Court, in my view, down a problematic path.”

His conclusion is damning: “It is important to recall what is at issue in Ernst. The case is not about whether the Charter was breached, or, if so, whether Charter damages are appropriate — rather, this case is about whether a claimant should have a chance to prove her allegations of a Charter breach warranting damages as a remedy, and whether a statute can bar her from having such an opportunity. In my view, by upholding the validity of a statute to bar a Charter remedy, this first judgment of 2017 has damaging potential to erode the enforcement of Charter rights.”

Meanwhile, Ernst submitted her letter to Canada’s chief justice on the separate ruling of Abella, a highly regarded jurist.

In her ruling, Abella characterizes Ernst a “vexatious litigant” and attributes the description to the regulator: “When the Board made the decision to stop communicating with Ernst, in essence finding her to be a vexatious litigant, it was exercising its discretionary authority under its enabling legislation.”

But the label doesn’t fit Ernst at all or accurately reflect the facts of the case.

In 2004, when Ernst began dealing with the regulator, she wasn’t suing anybody. “I was a landowner suffering endless sleepless nights because of Encana’s many unattenuated compressors near my home. I was the subject of lies and bullying by the company and regulator,” she writes in her letter to McLachlin.

Ernst, whose lawsuit against Encana still hasn’t made it to trial after 10 years, wrote that she tried to get the regulator “to engage honestly and respectfully with me and others impacted in my community, to enforce the regulations and appropriately address Encana’s non-compliances. I studied Encana’s noise assessments and the regulator’s deregulation; I documented their fraudulent and outright misrepresentations. Many in my community raised concerns. When we asked Encana if there was fracking in our community, we were told no (two years later, I found out Encana had already by that time repeatedly fractured into our drinking water aquifers).

“I was not a ‘litigant’ at that time, so it was impossible for me to be a ‘vexatious’ one.”

Four judges made no mention of the legal slur, while four dissenting judges, including the chief justice, found that Abella’s comments weren’t grounded in the facts, either. “We see no basis for our colleague’s characterization,” they wrote.

Ernst has respectfully asked that Abella’s statements be retracted or corrected for three important reasons.

“1) The two defendants remaining in my lawsuit may attempt to use Justice Abella’s statements against me;

“2) Justice Abella’s statements could prejudice future judges against me; and

“3) I continue to live with escalating harmful energy industry impacts, where the regulator — with no public interest in their mandate since 2013 — has established they are punitive towards me, and may also attempt to use Justice Abella’s statements against me.”

Ernst has now waited a decade to present her evidence on corporate contamination of groundwater and government negligence in the courts of Canada. To date, she has spent more than $350,000 seeking accountability with no end in sight.

No court has yet reviewed or heard a scintilla of evidence.

Just imagine how long Ernst might have to wait for the highest court in the land to correct “a false and seriously damaging” characterization in a ruling — let alone undo the damage of a ruling that effectively erodes the nation’s freedoms.