That appearance of cooperation, of a contract that unites two unequal parties against the prying eyes of the world, diminishes the women while absolving the men. … It is as if, with their money and influence, Weinstein and his ilk [Encana, Supreme Court of Canada and Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench justices, AER (and ERCB and EUB before it), Alberta Environment, Baytex, Bonavista, Angle/Bellatrix … and their lawyers?] have managed to buy shares in the ownership of reality itself.

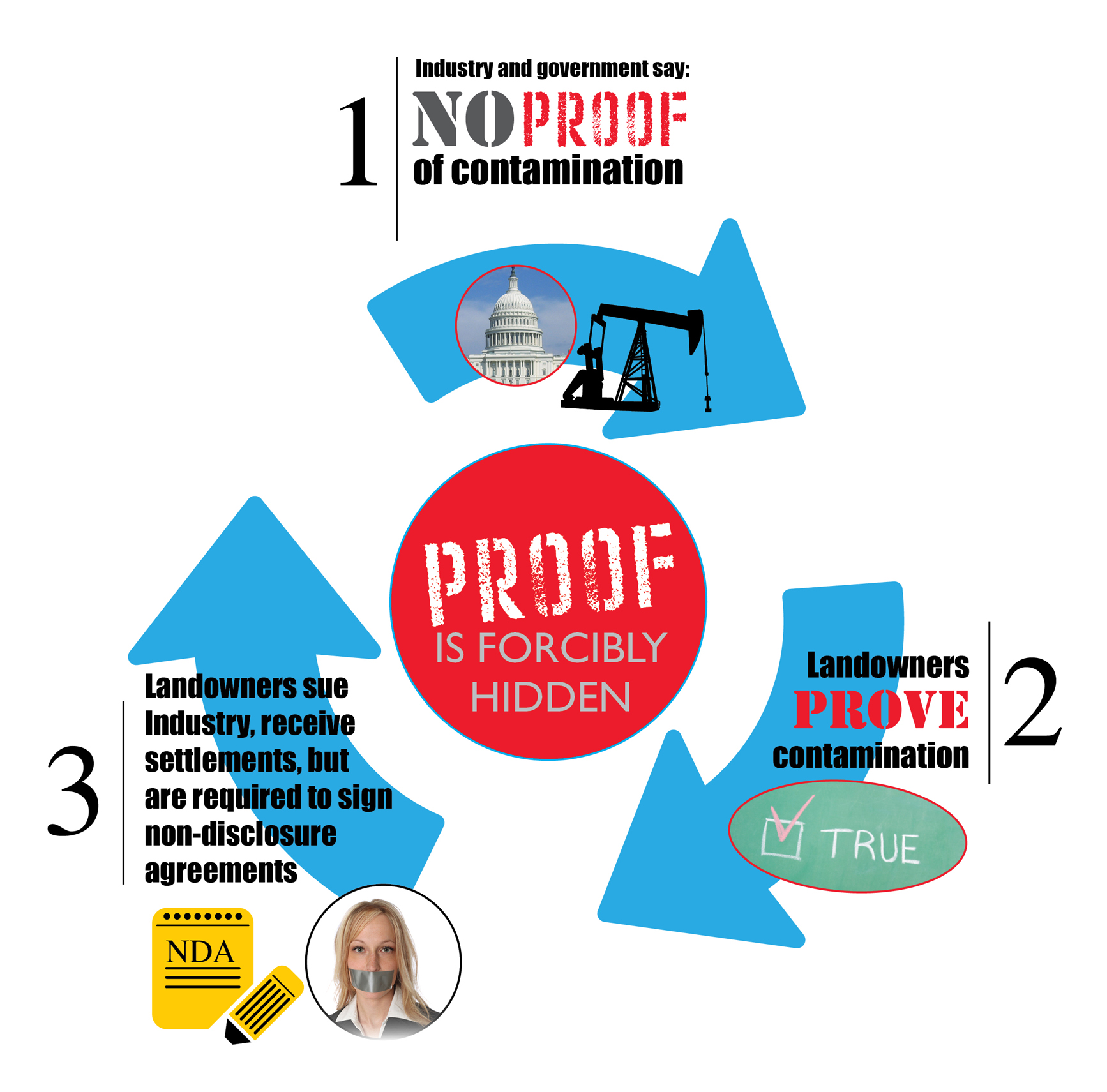

How many gags to cover-up oil and gas industry crimes and pollution have been ordered by judges in Alberta?

In Canada?

A province by province comparison of judicially ordered gags of corporate crimes is needed and would make fascinating study.

***

[Compare to:

2017 03 23: “Judges: a danger to Canadian women”

Lonnie Saken works for Bonavista:

Alberta lawyer Kieth Wilson also settled & gagged the Peace River area families poisoned by Baytex

2016 07 16: The Many Harms of Synergy Pound On: McLeod Lake Indian Band settles and gags, pulls out of lawsuit. BC Hydro: “the details of the (Impacts Benefits Agreement) are confidential.” [What a hideous name: “Impacts Benefits Agreement.” Did a judge, previously a corporate lawyer, came up with that?]

2014 04 04: Energy firms among top political donors in Alberta with Encana giving $30,516.50

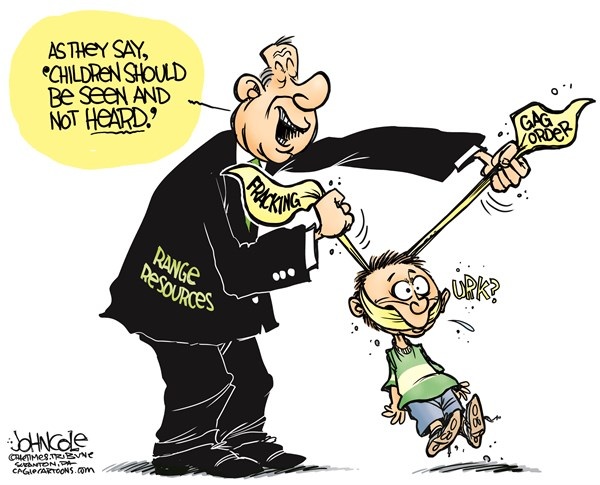

2013 09 03: Baytex Gag Order and Can You Silence a Child? Inside the Hallowich Case

2013 08 09: Fracking ‘silence’ for life: Gag orders on children & censored government data

2013 06 27: Steve Harper’s Gag Orders Sweep While Canadians Sleep

2013 06 09: Drillers Silence Fracking Claims With Sealed Settlements

2013 03 08: Steve Harper Government Gag Order for Scientists?

2012 08 27: Doctors fight “gag orders” over fracking chemicals

2012 07 21: ‘Medical Gag Rule’ Called An Illegal Gift to Gas Drillers

2012 05 12: Silencing Communities: How the Fracking Industry Keeps Its Secrets

2012 03 21: TINY DOSES OF GAS DRILLING CHEMICALS MAY HAVE BIG: HEALTH EFFECTS

2011 01 12: Settlement reached in gas-well incident

While Hanen was able to force various improvements in the plant operations in the 1970s and the 1980s, plant pollutants had seriously eroded both the environmental purity and property value of the ranch by 1990. Convinced that government and industry were working in tandem to ignore and silence her concerns, Hanen filed suit in 1991 against Esso and the Energy Resources Conservation Board of Alberta [since changed by the government to AER] for damages to the ranch’s cattle, soil, air and groundwater. While a settlement was ultimately achieved, the much more difficult task of finding ways of remedying, if not restoring the ranch’s environment is underway through the work of the Restoration Action Committee. There are a number of themes at work in the account given in this paper: the regulatory authority’s failure to regulate; political disinterest in redressing that failure; Esso’s refusal to acknowledge the extent of pollution and their strategy of portraying Hanen as a corporate adversary; the insignificance of the community’s role in the dispute; and perhaps most clearly, the utter lack of coherent management of remediation efforts after the groundwater pollution was confirmed in 1986….

Of course, the first thing that should be done is to immediately prevent any more input of contaminants. If the sources are not shut down, the problem will never be fixed. … [And that sums up the Evil of gag orders: they ensure the problems are never fixed. ]

Weinstein scandal puts nondisclosure agreements in the spotlight, The unfolding Weinstein scandal has sparked criticism that non-disclosure agreements allow powerful companies and individuals to stave off scrutiny and continue abusive practices. Now, there is a move afoot to place clear restrictions on their use by James Rufus, Oct. 23, 2017, LA Times

Harvey Weinstein. Bill O’Reilly. Roger Ailes. Bill Cosby. The Catholic Church.

All were able to skirt years and sometimes decades of allegations of sexual harassment or assault through the use of settlements or contracts that included nondisclosure agreements: legal provisions that swear employees or alleged victims to secrecy.

Those cases — and especially the unfolding Weinstein scandal — have sparked criticism that the agreements allow powerful companies and individuals to stave off scrutiny and continue abusive practices. Now, there is a move afoot to place clear restrictions on their use.

Last week, a group of Weinstein Co. employees, in a letter published by the New Yorker, sought to be released from their signed nondisclosure agreements, or NDAs.

“We ask that the company let us out of our NDAs immediately — and do the same for all former Weinstein Company employees — so we may speak openly, and get to the origins of what happened here, and how,” the unnamed employees wrote.

And just Monday, in an interview in the Financial Times, Zelda Perkins, who worked as Weinstein’s assistant in the London office of Miramax, his former production company, broke a nondisclosure agreement she said she and another worker signed in 1998. [Humanity and the environment would be well served if citizens under gag, especially those ordered gagged by judges and or companies, make their gags public.]

“Unless somebody does this there won’t be a debate about how egregious these agreements are and the amount of duress that victims are put under,” she is quoted as saying in the article, which details how she was allegedly sexually harassed and her co-worker sexually assaulted by Weinstein, who denied the allegations.

These confidentiality agreements have become a ubiquitous legal tool for purposes both controversial and benign, such as protecting trade secrets or confidential financial information.

Nondisclosure clauses in employment contracts and severance agreements prevent employees or former employees from badmouthing their bosses. Generally, as part of a private settlement, one party agrees to drop potential or unresolved legal action in exchange for a payment — and their silence.

The latest high-profile instance of such an agreement surfaced late last week when it was reported that in January, former Fox News anchor O’Reilly paid $32 million in a confidential settlement over a threatened sexual harassment lawsuit.

Cathy Schulman, an Oscar-winning filmmaker who is president of the Women in Film advocacy group, said such deals are part of a “silencing culture” in Hollywood.

“If a person complains about their work culture, what they usually hear is: ‘It’s time to move you to another workforce. Let’s settle this out,’” Schulman said.

“They are asked to make a deal with the devil. They are asked to sign and shut up. And then you plan your exit, I’ve done it myself.”

[Compare to sign and shut up deals in Alberta’s oil patch:

AER’s outside counsel, Glenn Solomon

End Compare: Sign and shut up in Alberta’s oil patch]

But in some cases, signing these secret agreements can benefit an individual victim, even if it allows bad behavior to continue, said Gloria Allred, the high-profile L.A. attorney whose firm has negotiated confidential settlements — and who is representing some of Weinstein’s accusers.

“If she resolves it in a way that’s positive for her and that she feels good about, then that’s what’s most important,” said Allred, who has a reputation for litigating in the press when she feels it’s in her clients’ interest. “And yes, it may mean that others may not know. But should it be mandated that no settlement should be confidential? We don’t think it’s a good idea.” [Think of the money lawyers would not get if gag orders covering-up corporate crimes were illegal! It’s no wonder lawyers and judges pimp and protect them.]

Full Coverage: Harvey Weinstein sexual harassment scandal

Without confidentiality agreements, many companies and high-profile individuals will choose not to settle and instead take their chances in court, which is not right for every victim, she said.

“The alternative is facing years of litigation and the risks inherent to that and the expense inherent to that,” she said. “That’s going to be hard on our clients.” [Legal matters are dreadfully inefficient and wasteful. Intentionally set up that way to ensure lawsuits are impossibly expensive and nasty, and drag on for decades so that harmed citizens are forced to settle and gag?]

In fact, there are already limits on confidentiality agreements, though individuals who sign them may not be aware — a fact that can make NDAs more effective in practice than they might be in theory.

Wayne Outten, a New York employment lawyer and co-founder of the nonprofit Workplace Fairness, said all such agreements, whether in a severance contract or a private settlement, allow victims to report harassment, discrimination and criminal activity to authorities.

“No matter what somebody has signed, they’re free to go to the government,” Outten said. “It’s a matter of public policy.” [But not the public or media? What good will going to the government do? Many governments enable the crimes being covered-up by the gag orders ordered by judges appointed by those corrupt governments!]

For instance, employees can report alleged harassment to the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, crime victims can file reports with the police and corporate whistleblowers can contact the Securities and Exchange Commission.

What’s more, under California law, confidentiality agreements are not enforceable if they are attached to civil settlements involving some potential crimes, including felony sexual assault and child sex abuse.

In such a case, if a victim broke the confidentiality agreement, a court could reject a breach of contract lawsuit. [But more and more courts, including Canada’s Supreme Court, are proving themselves corporate crime enablers. Breach of gag orders ought never be reviewed in any court, especially not in courts that order gag orders or seal evidence of crimes shut! And the harmed citizen still has to come up with masses of time and funding to make it to the point of a court rejecting breach of contract or gag order, with the criminal corporations throwing bankrupting bombs of expensive delays and abusive legal harassment, enabled by the same court!] There’s no law forbidding confidential settlements in matters that don’t rise to the level of a felony, though there may be a push in Sacramento next year to bar such settlements in harassment cases too following the Weinstein scandal.

Still, regardless of various exceptions and even in cases where an agreement might be invalidated by a court, people who sign nondisclosure agreements tend to abide by them. [And that is the cruel abusive impact of gag orders: victims are re-victimized, abused for the duration of their lives, often by the very judges paid to uphold the law!]

“An attorney can say a confidentiality agreement is not enforceable, but a victim might say, ‘I don’t care, I’m not saying anything,’” said Assemblyman Mark Stone (D-Scotts Valley), who authored a 2016 law that added child sex abuse to the list of potential crimes where a confidential civil settlement is not allowed.

Attorneys say many individuals who sign them believe an NDA applies more broadly than it truly does.

“I’ve seen plenty of confidentiality agreements that don’t mention any exceptions whatsoever, whether ones that are agreed to or that the law recognizes,” said Sherman Oaks litigator David Krause-Leemon. “I don’t know if the intent is to create a perception that there are no exceptions, but from a defense point of view you’d be better off if the plaintiff had that perception.”

That can make someone hesitant to speak even when they’re allowed to.

Los Angeles consumer attorney Brian Kabateck said he’s sometimes had trouble getting people who have signed NDAs to testify in court — something such agreements generally must allow.

“They’ll avoid service of the subpoena. They’re terrified,” he said, and with good reason.

Breaking a nondisclosure agreement can be expensive.

The agreements often spell out the financial consequences of a breach, and the recipient of the settlement could have to pay damages that exceed the amount received initially.

Indeed, the agreement that Perkins said she signed in London expressly stated that she will “use all reasonable endeavours to limit the scope of the disclosure as far as possible” in any criminal proceedings, according to legal documents cited in the Financial Times article.

Still, it’s rare for companies to take action when nondisclosure agreements are broken, in part because it would look bad, said Helene Wasserman, a partner at Littler Mendelson, a law firm that specializes in representing companies in employment matters.

“I’ve never had a client say, ‘We know this person breached confidentiality, let’s go after them,’” she said. “I can’t imagine many companies would want that kind of publicity. And those are the cases that would get publicity.”

While such cases are rare, they’re not unheard of.

In one high-profile case, Bill Cosby last year sued one of his accusers for breach of contract, saying she had violated a decade-old nondisclosure agreement by agreeing to be interviewed by local prosecutors in Pennsylvania.

Andrea Constand had sued Cosby in 2005, accusing him of drugging and sexually assaulting her. The two reached a settlement, complete with a confidentiality agreement, the following year. In 2015, after numerous women came forward to accuse Cosby, investigators with the Montgomery County district attorney’s office re-interviewed Constand.

Cosby’s lawyers argued that Constand “had no legal obligation to cooperate with investigators” because she is a Canadian citizen and that her cooperation amounted to a breach of the confidentiality agreement. [It’s no wonder lawyers are detested by so many]

A federal judge threw out that claim, saying a confidentiality agreement that forbids speaking to law enforcement is not enforceable.

But Kabateck said that the fact that Constand was even threatened with a breach of contract suit illustrates why some victims — even when protected by the law — are unwilling to step forward.

“It has a chilling effect,” he said. [Emphasis added]

Above image source: Texas Sharon

More:

New York attorney general launches investigation of Weinstein Co.

George Clooney and Matt Damon explain what and when they knew about Harvey Weinstein’s conduct

38 women have come forward to accuse director James Toback of sexual harassment

UPDATES:

6:15 p.m.: This article was updated with details from a Financial Times article about a nondisclosure agreement signed by a Miramax employee.

A few of the comments:

FoundStar 5 day(s) ago

NDA’s should be outlawed. They are nothing more than payment for burying crimes and misdemeanors. A payola that literally defends the criminal and/or company.

markmcintyre726 5 day(s) ago

One positive thing that’s come out of the Weinstein mess is the spotlight is focused on NDAs. Now let’s see what comes of it.

Criminals, predators and attorneys love the NDA.

Edgemont in reply to InkandQuill 5 day(s) ago

If NDAs crumble to dust, Hollywood will be in a state of absolute panic, not just over sexual matters. This is an industry that hides a lot of secrets on many levels. From major stars, directors, writers and the vast swarm of minions who power the secret machinery. That macho or leading lady star that drives the box office… not what they seem.

There would be millions more than “Hollywood” in panic. You’d find out how virtually every company is hiding all the ways they’ve poisoned, killed, cheated, committed fraud, harassment and on and on with their products, employees and general unsuspecting public.

Harvey Weinstein’s Ex-Assistant Breaks Confidentiality Agreement, Reveals Behind The Curtain by

Zelda Perkins, former assistant to disgraced film producer Harvey Weinstein, is the first of Weinstein’s accusers to break a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) to reveal further details about the alleged sexual harassment she endured.

The NDA is said to have been written up in October 1998, and in Perkins’ case, she claims to have shared a £250,000 settlement with another woman, who also alleges she was sexually assaulted by Weinstein.

In an interview with The Financial Times, Perkins revealed that she violated the NDA to expose the supposed legal secrecy of Weinstein, The Weinstein Company, Miramax and the companies’ legal teams. She also referenced the now-dozens of women who claim to have suffered at the hands of Weinstein, and she doesn’t want that suffering to be in vain.

Perkins is also aware that she may yet still face legal ramifications for breaking the NDA.

“I want to publicly break my non-disclosure agreement,” she told the FT. “Unless somebody does this there won’t be a debate about how egregious these agreements are and the amount of duress that victims are put under. My entire world fell in because I thought the law was there to protect those who abided by it. I discovered that it had nothing to do with right and wrong and everything to do with money and power.”

Perkins was one of the original Weinstein accusers in the bombshell New York Times article, but due to the NDA she couldn’t reveal any details of her specific case.

Now “free” to tell her story, Perkins alleges that Weinstein repeatedly sexually harassed her while working for Miramax out of the London office. She claims the first incident took place when Weinstein allegedly asked her to give him a massage while he was wearing only his underwear (a disturbingly similar allegation of many other women in this case). She says she declined.

Ranging from A-list actors to young up-and-comers, women of all stripes have emerged to accuse 65-year-old Weinstein, substantiating the supposed “open secret” of his behaviour towards women.

So far, at least 52 women have made accusations, and their tales each have elements in common. Weinstein, through his representative, has denied all accusations of non-consensual sex.

“This was his behaviour on every occasion I was alone with him,” she said. “I often had to wake him up in the hotel in the mornings and he would try to pull me into bed.”

When a colleague was allegedly assaulted in 1998, Perkins says she reached her breaking point, and the pair sought legal counsel.

“She was white as a sheet and shaking and in a very bad emotional state,” said Perkins. “She told me something terrible had happened. She was in shock and crying and finding it very hard to talk. I was furious, deeply upset and very shocked. I said, ‘We need to go to the police’ … but she was too distressed.” [What good would the police do? They too often further abuse victims to protect abusers, just at they do those harmed by oil and gas companies]

They were advised by lawyers to seek a settlement claim, and the negotiation began shortly afterwards. [Is there no limit to how abuse-enabling and abusive the legal/judicial industry is?]

Her signed NDA contains many clauses, which Perkins believes were designed to control her future behaviour. In her FT interview, she also alludes to Weinstein’s legal team and its function as a protective web around him so he could avoid consequences for his alleged behaviour.

One such clause was written in case she was asked to provide testimony about Weinstein or his business. If that hypothetical situation arose and “any criminal legal process” involving Weinstein or Miramax required her to give evidence, she would have to give 48 hours’ notice to a Weinstein lawyer “before making any disclosure.”

She claims she spent days being interrogated at the offices of Weinstein’s London lawyers — including a 12-hour Q&A session — in order to compose the NDA.

“I was pretty broken after the negotiation process,” she said. “I want to call into question the legitimacy of agreements where the inequality of power is so stark and relies on money rather than morality.”

Perkins admits she wasn’t allowed to keep a copy of her NDA, as part of the agreement. [!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Is disbarment needed of the lawyers involved?] She only has possession of a few pages, which were viewed by the FT.

She originally had grander plans to bring down Weinstein by publicly exposing his behaviour, but the lawyers were “reluctant.”

“They said words to the effect of, ‘They are not going to take your word against his with no evidence,’” she recalled. “I was very upset because the whole point was that we had to stop him by exposing his behaviour. I was warned that he and his lawyers would try to destroy my credibility if I went to court. They told me he would try to destroy me and my family.”

The FT reports that Weinstein, through a representative, denied Perkins’ accusations.

“The FT did not provide the identity of any individuals making these assertions,” said the spokesperson. “Any allegations of non-consensual sex are unequivocally denied by Mr. Weinstein. Mr. Weinstein has further confirmed that there were never any acts of retaliation against any women for refusing his advances.”

Weinstein is currently the subject of criminal investigations in Los Angeles, New York City and in the U.K. [Emphasis added]

The Devastating Sadness of Harvey Weinstein Purchasing His Alleged Victims’ Stories by Katy Waldman, October 11, 2017, The Slate

It took two comprehensive and chilling news reports, one from the New York Times and another from the New Yorker, to expose the truth about Harvey Weinstein. Before last Thursday, the film titan’s alleged sexual predations were an open secret to some, a flash in the peripheral vision of others.

Now accusations are pouring out from Hollywood stars and aspiring actresses and those who worked for Weinstein’s production company. This is the sound of a decades-long silence broken, of a raft of confidentiality clauses being torn apart.

[The same also needs to happen to the decades of confidentiality agreements covering-up oil and gas industry crimes and harms to public health, families, children, communities, infrastructure, wildlife, fish, environment, etc, especially the gags ordered by judges/courts.]

As Ronan Farrow explained in the New Yorker, “Weinstein and his associates used nondisclosure agreements, monetary payoffs, and legal threats to suppress [his accusers’] myriad stories.” Farrow’s piece quoted one female Weinstein Company employee anonymously, as “her lawyer advised her that she could be exposed to hundreds of thousands of dollars in lawsuits for violating the nondisclosure agreement attached to her employment contract.”

The Times reported that Weinstein himself also reached at least eight settlement agreements, with his accusers typically getting between $80,000 and $150,000 in return for their silence. Rose McGowan received a $100,000 payment in 1997, Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey wrote in the Times, “after an episode in a hotel room during the Sundance Film Festival. The $100,000 settlement was ‘not to be construed as an admission’ by Mr. Weinstein, but intended to ‘avoid litigation and buy peace,’ according to the legal document.”

Weinstein succeeded in purchasing “peace” with confidentiality agreements, at least for a time. There is a case to be made that such deals are beneficial to victims. As Vox writes, “a ban on confidentiality clauses in settlement agreements [could] reduce the size of payouts,” as defendants are likely willing to part with more money to settle claims on the sly. [Is the dirty money worth it?] But in the case of Weinstein and other powerful alleged abusers, these contracts become yet another tool to exploit those who’ve already been exploited. “It felt like David versus Goliath,” one former employee told the New Yorker about Weinstein’s legal maneuvers in the 1990s.

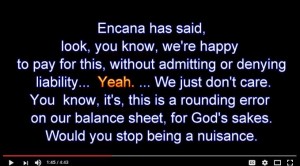

“The guy with all the money and the power flexing his muscle and quashing the allegations and getting rid of them.” [Like Encana? Like AER? Like Alberta Environment? Like the Supreme Court of Canada smearing Ernst to get rid of her damning documented evidence and protect law-violating oil companies via the AER?]

In deciding whether to accept a settlement with a prominent alleged harasser or abuser, women must choose between surrendering their stories (perhaps thereby perpetuating a cycle of abuse) and receiving no compensation for their suffering (and perhaps augmenting that suffering as the abuser retaliates). There is something devastatingly sad about this binary. What’s moral about a pact that predicates receiving justice on stifling your ability to describe the crime? [Perhaps the cure is to jail judges and lawyers that prepare and order gags and settlements, and jail judges who lie & defame citizens that are seeking justice for regulators covering-up corporate crimes? Currently, lawyers and judges engaging in these horrific and abusive practices get enormously rewarded and promoted instead.]

Literature is loud with ghoulish stories about women whose voices get stolen: Echo helplessly repeating others’ words; the princess Philomela, raped by the king of Thrace, who then cuts out her tongue to ensure her silence. There’s also Hans Christian Andersen’s tale of a sea hag ripping out a mermaid’s voice, an exchange that allows the maiden to walk on land and dance with the prince. This transaction makes the heroine look complicit in her own silencing, even though the power dynamics were always in the villain’s favor. [Like judges trying to publicly make victims of sexual assault complicit? And then there’s “knees together” ex judge Robin Camp.]

For men like Weinstein, R. Kelly, Bill O’Reilly, and Bill Cosby—just to name a few of the high-profile figures who’ve profited from nondisclosure agreements—gag orders brush a layer of volition over what is essentially intimidation. They create a self-serving tableau in which victims, rather than simply receiving restitution, are forced to barter for it. [Because legal systems around the world are so corrupt, controlled by abusers, including corporate polluters, with judges themselves arrogantly and nastily re-victimizing victims?]

That appearance of cooperation, of a contract that unites two unequal parties against the prying eyes of the world, diminishes the women while absolving the men. In signing a settlement agreement, a victim is coerced into a pose that compromises the public perception of her victimhood even as she cedes control of her narrative to unfriendly hands. It is as if, with their money and influence, Weinstein and his ilk have managed to buy shares in the ownership of reality itself. Meanwhile, the women they target must weigh the value of tending to their own lives against what is to be gained from protecting each other.

Law Firm that Silenced Harvey Weinstein Accusers also Involved in SIVs that Tanked Citigroup by Pam Martens and Russ Martens, October 24, 2017, Wall Street on Parade

Matthew Garrahan dropped a bigger bombshell in the Financial Times yesterday than even he realizes. Garrahan named the law firm that had crafted a gag order in 1998 to silence two women from ever speaking about their encounters with Harvey Weinstein. One woman, Zelda Perkins, was an assistant to Weinstein in London and charged him with egregious sexual harassment. The other unnamed female colleague charged Weinstein with sexual assault. The two were paid $125,000 each and given an iron-clad gag order. The terms of the gag order were so confidential that the women were not even allowed to have a full copy of what they had agreed to, just a summary of some of its terms.

The law firm representing Weinstein with the settlements and gag orders (officially called non-disclosure agreements) was Allen & Overy – the London derivatives powerhouse that also signed off on the Structured Investment Vehicles (SIVs) that played a significant role in helping to blow up Citigroup in 2008, resulting in the largest taxpayer bailout of a bank in financial history.

In 2007, according to Standard & Poor’s Structured Finance research reports, Citigroup was managing the following Structured Investment Vehicles that were incorporated in the Cayman Islands and not consolidated on Citigroup’s balance sheet: Centauri Corp., Beta Finance Corp., Sedna Finance Corp., Five Finance Corp., and Dorada Corp. In addition, according to press reports, Citigroup had created two more SIVs in 2006: Zela Finance Corp. and Vetra Finance Corp. The SIVs contained approximately $80 billion of mostly toxic debt, much of which ended up back on Citigroup’s balance sheet. Allen & Overy was the London counsel to Citigroup on these SIVs.

You don’t have to take our word for this. One of Allen & Overy’s own lawyers actually bragged on the law firm’s website about the key role it played in the “fascinating time” of the financial crisis – the most devastating economic collapse since the Great Depression that left millions of Americans out of work and foreclosure notices on their front door.

Elizabeth Collett described at the time on Allen & Overy’s website that 2007 summer and fall of financial hell as follows:

“The summer of 2007 was a fascinating time for those of us involved in the structured credit markets. Since I joined A&O’s derivatives and structured finance group as an associate in 2004 the capital markets had been growing very fast. With the onset of the credit crunch, however, our work changed from advising investment banks setting up complex finance structures to focusing on how existing structures would be affected by reduced liquidity and falling asset values.

“Structured Investment Vehicles (SIVs) were particularly hit hard given that they rely on constant funding and high credit ratings (which were, in part, reliant on the value of their assets). At its peak, the SIV market was worth around $400 billion (held by 30 vehicles), so it was not long before concern arose that these vehicles might start selling billions of dollars of assets into an already volatile market. In the early Autumn of 2007 the US Treasury called in a number of the biggest US investment banks and asked them to come up with a solution to the problem. Citibank, the largest of them, and the market leader in terms of managing SIVs, took on the challenge. Given A&O’s wealth of experience in advising on SIVs and, in particular, as Citibank’s English counsel on all the SIVs managed by them, we were the natural choice to advise and were therefore the first to be instructed.

“Although by the time the transaction ended there were six law firms (A&O being the only English law advisers), three structuring banks and an investment manager involved, I was fortunate enough to see the deal progress from the beginning. What came out of Citibank’s proposals, developed with our advice, was the Master Liquidity Enhancement Conduit (MLEC or, as the press dubbed it, the ‘Super-SIV’). I was the lead associate in the A&O team, working with five partners and a number of other associates. I was involved at every stage including co-ordinating the A&O team, drafting parts of the term sheet, participating in conference calls to brainstorm the structure, reviewing and commenting on transaction documents and preparing draft agreements. Over the following two months the media coverage of the transaction gathered momentum (unsurprisingly since it was intended as a $100 billion solution to the SIV crisis) until there were almost daily reports on its progress in the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal. It was fascinating to be working on such a high profile and politically sensitive transaction, and the media attention highlighted the fact that Allen & Overy is at the very forefront of the legal world in capital markets.”

The Master Liquidity Enhancement Conduit never made it off the ground as major Wall Street firms saw it for what it was – a not so subtle effort to bail out Citigroup by getting big Wall Street firms to chip in.

What actually saved Citigroup was a gun to the head of the taxpayer. Before it was all over, the U.S. Treasury pumped $45 billion in capital into Citigroup; the government guaranteed over $300 billion of Citigroup’s assets; the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) guaranteed $5.75 billion of its senior unsecured debt and $26 billion of its commercial paper and interbank deposits; and the Federal Reserve secretly sluiced $2.5 trillion, cumulatively, in almost zero-interest loans to Citigroup.

And here’s the really sad part: to this day no one knows why Citigroup was worth saving. Its serial violations have continued since its bailout, including a felony count to which it admitted in 2015 related to its participation in a cartel to rig the foreign exchange market.

As for the legal cunning of Allen & Overy, the Financial Times describes its gag order for Zelda Perkins in the Weinstein matter as follows:

“There are plenty of clauses in it to direct and curtail her future behaviour, including if she were ever asked to provide testimony. One says that if ‘any criminal legal process’ involving Harvey Weinstein or Miramax requires her to give evidence, she will give 48 hours notice to Mark Mansell, a lawyer at Allen & Overy, ‘before making any disclosure’.

“In the event her evidence is required, ‘you [she] will use all reasonable endeavours to limit the scope of the disclosure as far as possible’, the agreement says, adding that she will agree to give ‘reasonable assistance’ to Miramax ‘if it elects to contest such process’.

According to the Financial Times, this gag order was signed in 1998. It buried for the past 19 years a claim of sexual assault by Harvey Weinstein – a charge that rightfully belonged with the police.

At the peak of the financial crisis, Citigroup was trading as a 99 cent stock. Its shareholders lost the vast majority of their money and then the company did a 1-for-10 reverse split, leaving shareholders with 100 shares for every 1,000 shares they had previously owned.

Today, the Weinstein Company is struggling to financially survive; its Board is under a cloud; its reputation is in tatters; multiple investigations are underway. The Weinstein Company is where Citigroup was in 2008. Is it just possible that neither received wise counsel from Allen & Overy?

[Emphasis added]

***

Last two slides of Ernst Presentation to UNANIMA, UN Church Centre, New York City, October 1, 2011, at celebration for receiving International Woman of Courage Award

***

In Ernst vs AER, did the Supreme Court of Canada intentionally publish Rosalie Abella’s lie of AER finding Ernst to be a “vexatious litigant” and repeat it in the summary the court sent to media because Ernst has publicly stated gag orders on drinking water pollution by oil and gas companies must be made illegal and that she will not settle and gag the law violations by Encana, Alberta Environment and AER?

Supreme Court of Canada definition of Vexatious Litigant: A citizen diligently providing documented evidence of corporate crimes to an energy regulator to protect the public interest and public health.