Red Deer’s poor air quality report sparks government reaction by Darcy Henton, May 1, 2016, Calgary Herald

Last fall’s poor air quality report for Red Deer and other parts of the province was akin to a doctor’s warning that a patient has high blood pressure, says Alberta’s air quality director.

Hamid Namsechi said the problem is serious and cannot be ignored, but it’s not like the sky is falling.

“Right now, the problem isn’t dire,” he said. “Nobody needs to be overly alarmed. This is just a reminder that we need to be more frugal in how much we emit into our airshed.”

The Canadian Ambient Air Quality Standards report released last September warned that the Red Deer area in central Alberta exceeded the limits for national air quality standards, and four other regions of the province were approaching limits.

Namsechi said the warning can’t be ignored and a provincial air quality plan released last week will go a long way to addressing those concerns before they become critical.

“I’m very optimistic we can get ahead of this issue,” he said.

Albertans have to realize there are consequences to their daily lifestyle choices and what they do can have an effect on the air they breathe, he said.

“We need to manage our environmental footprint,” Namsechi said. “We need to live within the environmental budget of our airsheds and watersheds. Everybody needs to be part of the solution.” [Oil and gas companies too, or are they exempt, as usual?]

It’s not just a government or industry problem, he added.

“This problem is here because everybody is a contributor.”

Namsechi said last year’s report wasn’t a huge surprise.

Red Deer actually exceeded national limits three years in a row, and the government and local groups had already been working on a plan for two years to address the problem, he said. [Typical Synergy Alberta – all talk, planning & promises, no action. All to enable the polluters]

Last week, the province gave $250,000 to a local organization for monitoring aimed at identifying the sources of the pollution, and $560,000 for a second air monitoring station in south Red Deer.

Provincially, the government aims to have an air monitoring station in every community of more than 20,000 people.

Namsechi said 20 communities of more than 20,000 already have stations, as well as 14 communities under 20,000. [In true Synergy Alberta/SPOG betrayal and trickery, are the stations all located upwind of the worst offending facilities?] The only communities with a population of more than 20,000 without monitoring stations are Leduc, Lloydminster and Airdrie, and the latter is getting one in 2017.

Alberta has more monitoring stations than any other province in Canada, with nearly 140 — about half operated by industry. [Welcome to Synergy Alberta & SPOG!]

Each station costs about $300,000, plus $100,000 annually to operate.

The province also has portable monitors and a mobile lab.

Air quality management plans are now being developed for the other five zones in the province with the initial focus on the four nearing the national limit — South Saskatchewan River, North Saskatchewan River, Upper Athabasca River and Lower Athabasca River, Namsechi said.

The plans must be completed by September 2017, he added. [Two years of planning done with no pollution reduction, two more years of planning = four years of planning to accomplish nothing. Exactly what the polluting companies want. Why not order the companies to disclose all chemicals used so that Albertans know what toxic chemicals they and their children and livestock, pets are breathing day in, day out, drinking in their contaminated water and order the companies to mitigate their pollution instead of plan & monitor it year in, year out (aka, cover it up)?]

In addition, the Clean Air Strategic Alliance (CASA) has been asked to identify solutions for reducing emissions from smaller sources, called non-point sources, in the Red Deer area that can be applied across the province. [How many years will that take? The solutions are obvious. Order the companies to stop polluting, if they can’t, order the companies shut down! Easy, can start on May 2, 2016, no more planning or identifying needed to clean up Alberta’s poisonous (and very noisy) air]

While most emissions come from point sources such as industry smokestacks, about 25 per cent of emissions come from non-point sources, including vehicles, residences, small businesses and oil and gas facilities, Namsechi said.

[What are you children breathing in Alberta?

Cochrane Interpipeline Gas Plant NW of Calgary, Alberta

Alberta frac sites: Hold your breath all day and night long. ]

CASA executive director Keith Denman said a project team will work over the next year to determine what non-point emission sources are having the biggest effect, and study what’s been done in other jurisdictions to reduce emissions.

“If we come up with recommendations the industry folks, the environmental groups and the health groups are all able to agree on, [Synergy Alberta & SPOG wrecking publich health, again. There is no need for agreement. Order the pollution stopped. Simple. Synergy makes certain that only industry gets what it wants, the rest be damned. Lack of “agreement” of how we’ll continue being poisoned, will ensure that the polluters continue, uninterupted] that makes it much easier for the government to implement,” he said.

Namsechi said the government will tackle large emitters through emission standards that come up for renewal at many industrial facilities over the next two years [Oil and gas companies and their contractors and subcontractors excluded?], while the NDP government’s plan to phase-out all coal-fired electrical generation by 2030 will have a huge positive impact on air quality.

Air quality consultant David Spink said the province is on the right track.

“I don’t want to alarm people, but . . . we know for a fact our air quality shortens some people’s lives.”

He said there’s nothing immediate that can be done [That’s complete hogwash! Pollution reductions could have been ordered years ago or have oil and gas companies threatened to sue under NAFTA and TILMA?] that will change air quality overnight, but it’s an issue that, like high blood pressure, cannot be ignored.

“I think the government is taking it seriously,” [How pathetic is that statement? If this were true, the government would have ordered pollution reductions long ago and stopped with the go nowhere planning and synergizing with the intent to lie and con the poisoned, help the AER deregulate as fast as they can, to enable dramatic increases in the poisoning allowed by industry] he said.

“We’ll just have to see what actions are taken.” [Emphasis added]

Study: US oil field source of global uptick in air pollution by Michael Biesecker & Matthew Brown, April 30th 2016, National Observer

An oil and natural gas field in the western United States is largely responsible for a global uptick of the air pollutant ethane, according to a new study.

The team led by researchers at the University of Michigan found that fossil fuel production at the Bakken Formation in North Dakota and Montana is emitting roughly 2 per cent of the ethane detected in the Earth’s atmosphere.

Along with its chemical cousin methane, ethane is a hydrocarbon that is a significant component of natural gas. Once in the atmosphere, ethane reacts with sunlight to form ozone, which can trigger asthma attacks and other respiratory problems, especially in children and the elderly. Ethane pollution can also harm agricultural crops. Ozone also ranks as the third−largest contributor to human−caused global warming after carbon dioxide and methane.

“We didn’t expect one region to have such a global influence,” said Eric Kort, lead author of the study and an assistant professor of climatic science at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The study was launched after a mountaintop sensor in the European Alps began registering surprising spikes in ethane concentrations in the atmosphere starting in 2010, following decades of declines. The increase, which has continued over the last five years, was noted at the same time new horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing techniques were fueling a boom of oil and gas production from previously inaccessible shale rock formations in the United States.

Searching for the source of the ethane, an aircraft from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2014 sampled air from directly overhead and downwind of drilling rigs in the Bakken region. Those measurements showed ethane emissions far higher than what was being reported to the government by oil and gas companies.

The findings solve an atmospheric mystery — where that extra ethane was coming from, said Colm Sweeney, a study co−author from the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

The researchers said other U.S. oil and gas fields, especially the Eagle Ford in Texas, are also likely contributing to the global rise in ethane concentrations. Ethane gets into the air through leaks from drilling rigs, gas storage facilities and pipelines, as well as from intentional venting and gas burnoffs from extraction operations.

“We need to take these regions into account because it could really be impacting air quality in a way that might matter across North America,” Kort said.

Helping drive the high emission levels from the Bakken has been the oil field’s meteoric growth. Efforts to install and maintain equipment to capture ethane and other volatile gases before they can escape have lagged behind drilling, said North Dakota Environmental Health Chief Dave Glatt.

Glatt’s agency has stepped up enforcement efforts in response. Last year, the state purchased a specialized camera that can detect so−called fugitive gas emissions as they escape from uncontained oil storage tanks, leaky pipelines, processing facilities and other sources.

“You’re able to see what the naked eye can’t and it reveals emissions sources you didn’t know where there,” Glatt said. “It’s a game changer. A lot of the companies thought they were in good shape, and they looked through the camera and saw they weren’t.”

Regulators at the Environmental Protection Agency were reviewing the study’s results. Spokeswoman Laura Allen said Friday that new clean air rules recently announced by the Obama administration to curb climate−warming methane leaks from oil and gas drilling operations should also help address the harmful ethane emissions.

There are other ways ethane gets into the atmosphere — including wildfires and natural seepage from underground gas reserves. But fossil fuel extraction is the dominant source, accounting for roughly 60 to 70 per cent of global emissions, according to a 2013 study from researchers at the University of California. [Emphasis added]

The U.S. oil and gas boom is having global atmospheric consequences, scientists suggest by Chelsea Harvey April 28, 2016, Washington Post

Scientists say they have made a startling discovery about the link between domestic oil and gas development and the world’s levels of atmospheric ethane — a carbon compound that can both damage air quality and contribute to climate change. A new study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters has revealed that the Bakken Shale formation, a region of intensely increasing recent oil production centered in North Dakota and Montana, accounts for about 2 percent of the entire world’s ethane output — and, in fact, may be partly responsible for reversing a decades-long decline in global ethane emissions.

The findings are important for several reasons. First, ethane output can play a big role in local air quality — when it is released into the atmosphere, it interacts with hydrogen and carbon and can cause ozone to form close to the Earth, where it is considered a pollutant that can irritate or damage the lungs.

Ethane is also technically a greenhouse gas, although its lifetime is so short that it is not considered a primary threat to the climate. That said, its presence can help extend the lifespan of methane — a more potent greenhouse gas — in the atmosphere. This, coupled with ethane’s role in the formation of ozone, makes it a significant environmental concern.

From 1987 until about 2009, scientists observed a decreasing trend in global ethane emissions, from 14.3 million metric tons per year to 11.3 million metric tons. But starting in 2009 or 2010, ethane emissions starting rising again — and scientists began to suspect that an increase in shale oil and gas production in the United States was at least partly to blame. The new study’s findings suggest that this may be the case.

The study took place during May 2014. A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) aircraft flew over the Bakken Shale and collected data on airborne ethane and methane, as well as ozone, carbon dioxide and other gases.

“We were interested in understanding the atmospheric impacts of some of these oil and gas fields in the U.S. — particularly oil and gas fields that had a lot of expansion of activities in the last decade,” said Eric Kort, the study’s lead author and an atmospheric science professor at the University of Michigan.

The findings were jarring.

“We found that in order to produce the signals we saw on the plane, it would require emissions in the Bakken to be very large for ethane … equivalent to 2 percent of global emissions, which is a very big number for one small region in the U.S.,” Kort said.

Notably, he said, the team’s observations in the Bakken Shale helped shed some light on the mysterious uptick in global ethane emissions observed over the past few years.

“The Bakken on its own cannot explain the complete turn, but it plays a really large role in the change in the global growth rate,” Kort said.

On a regional level, the researchers pointed out that a deeper investigation into the Bakken emissions impact on ozone formation may be warranted — not only for the purpose of analyzing local air quality but also because current models of the atmosphere have not included the jump in ethane output.

Because the researchers were also measuring other gases during the flyovers — including ozone, carbon dioxide and methane — they were able to make another major discovery. They found that the ratio of ethane to methane produced by the Bakken was much higher than what has been observed in many other shale oil and gas fields in the United States — an observation that could have big implications for future methane assessments, which are important for climate scientists.

In many oil and gas fields, methane is often the primary natural gas present — sometimes accounting for up to 90 percent or more of the gas that is released during extraction. Ethane often tends to be present in smaller proportions. In the Bakken, however, the researchers found that ethane accounted for nearly 50 percent of all the natural gas composition, while methane was closer to 20 percent.

This is important because researchers sometimes use trends in global ethane emissions to make assumptions about the amount of methane that’s being released by fossil fuel-related activities. While it’s possible to measure the total methane concentration in the atmosphere, it’s difficult to say exactly where that methane came from, because there are so many possibilities: thawing permafrost in the Arctic, emissions from landfills and agriculture are just a few examples. But because ethane is primarily emitted as a byproduct of fossil fuel development — and because methane and ethane tend to be emitted together in those cases — researchers sometimes use trends in global ethane emissions to make assumptions about how much of the Earth’s methane output can be attributed to oil and gas development.

When global ethane emissions were declining, for instance, many researchers assumed that overall losses of natural gas during fossil fuel extraction were declining, Kort noted. And when ethane emissions began rising again, it was logical to assume that methane emissions — from oil and gas development, specifically — were also likely on the rise. But as the Bakken study points out, this is not necessarily the case. The new study suggests that the Bakken formation has accounted for much of the global increase in ethane emissions while emitting comparatively low levels of methane simultaneously. And the researchers believe that there are other locations in the United States — the Eagle Ford shale in Texas, for example — where conditions are similar.

“They’ve basically shown here that a single shale can account for most of the ethane increase that you’ve seen in the past year,” said Christian Frankenberg, an environmental science and engineering professor at the California Institute of Technology and a researcher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. (Frankenberg was not involved with this study, although he has collaborated with Kort in the past.)

“This is not to say that there’s no enhanced methane in these areas,” he added. But he pointed out that making an incorrect assumption about the ratio of methane escaping compared to ethane “might easily overestimate the methane increases in these areas.”

And making incorrect assumptions about the methane that’s entering the atmosphere alongside ethane can skew climate scientists’ understanding of where the Earth’s methane emissions are coming from and which sources are the biggest priorities when it comes to managing greenhouse gas emissions.

Thus, while the new study contains striking findings about ethane emissions, it perhaps only deepens the already large and contentious mystery over just how much the U.S. oil and gas boom is contributing to emissions of methane, which is widely regarded to be the second most important greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide.

More broadly, the paper also highlights the immense impact that fossil fuel development in the United States can have on the atmosphere — and how important it is from both an air quality and a climate perspective to closely monitor these activities. As the paper points out, domestic production is already being felt on a global level.

“Ethane globally had been declining from the 80s until about 2009, 2010 … and nobody was really sure why it was increasing in the atmosphere again,” Kort said. “Our measurements showed this one region could explain much of the change in global ethane levels and kind of illustrate the roles these shale plains could play.” [Emphasis added]

The Study:

Fugitive emissions from the Bakken shale illustrate role of shale production in global ethane shift by E. A. Kort, M. L. Smith1, L. T. Murray, A. Gvakharia, A. R. Brandt, J. Peischl, T. B. Ryerson5, C. Sweeney, K. Travis, April 2016, doi: 10.1002/2016GL068703 ©2016 American Geophysical Union

This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record.

Abstract

Ethane is the second most abundant atmospheric hydrocarbon, exerts a strong influence on tropospheric ozone, and reduces the atmosphere’s oxidative capacity. Global observations showed declining ethane abundances from 1984 to 2010, while a regional measurement indicated increasing levels since 2009, with the reason for this subject to speculation.

The Bakken shale is an oil and gas-producing formation centered in North Dakota that experienced a rapid increase in production beginning in 2010. We use airborne data collected over the North Dakota portion of the Bakken shale in 2014 to calculate ethane emissions of 0.23 0.07 (2) Tg/yr, equivalent to 1-3% of total global sources. Emissions of this magnitude impact air quality via concurrent increases in tropospheric ozone. This recently developed large ethane source from one location illustrates the key role of shale oil and gas production in rising global ethane levels.

Key Points:

- The Bakken shale in North Dakota accounted for 1-3% total global ethane emissions in 2014

- These findings highlight the importance of shale production in global atmospheric ethane shift

- These emissions impact air quality and influence interpretations of recent global methane changes [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to:

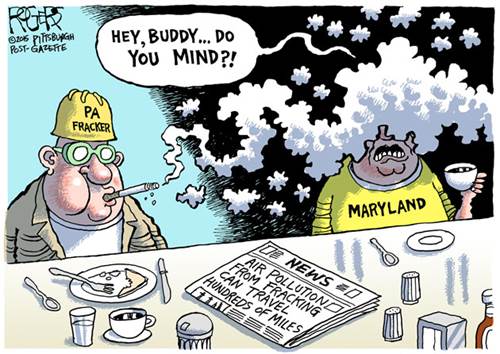

2015 04 30: New Study says Fracking Wells Could Pollute The Air Hundreds Of Miles Away

2015 08 30: Toxic taint: Tests in Alberta industrial heartland reveal air-quality concerns

Bob Willard, Senior advisor at the Alberta Energy Regulator, agreed to speak about current regulations.

David Kattenburg: Why aren’t these things being monitored for in the gases that are coming out from flaring and incineration stacks?

Bob: The long list that you’ve identified would be the responsibility for monitoring of not only the Alberta Energy Regulator, but the Environment department themselves, and I would direct you once again to ESRD for them to identify what their plans are relative to updating those guidelines.

David: I have actually, I’ve tried valiantly I’d say to try to get them to explain to me why they have these guidelines that say all industry MUST conform to these guidelines, and then I said well why does directive 60 of the Alberta Energy Regulator only establish monitoring requirements for sulfur dioxide and he said: “speak to the Alberta Energy Regulator.”

Bob: Um, it is important, and this is something the Energy Regulator does lead, is capturing the metrics of the volumes of material, so we do have good metrics as to the volumetrics.

David: But essentially nothing about the composition of those gases, other than sulfur dioxide.

Bob: A totally accurate composition, I would certainly volunteer that no, we do not have a totally accurate comprehensive information on the flare composition rather, we have it for the uh volumes, but not necessarily for the compositions. ]

2012 ERCB (now AER) lawyer letter to Ernst (in response to repeat requests by Ernst for chemical disclosure of fracturing fluids injected by EnCana into Rosebud drinking water aquifers and in approximately 200 gas wells fractured above the Base of Groundwater Protection around Rosebud.)

“However, the ERCB does not currently require licensees to provide detailed disclosure of the chemical composition of fracturing fluids.”

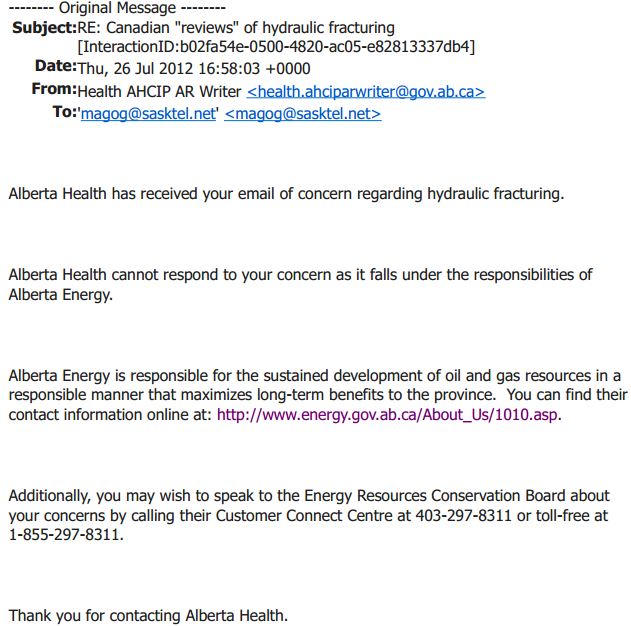

2012 07: Jessica Ernst’s query on frac health harms to the Canadian Council of Academies Frac Review Panel, and federal and provincial agencies on health harms caused by fracing. Alberta Health’s response to Ernst:

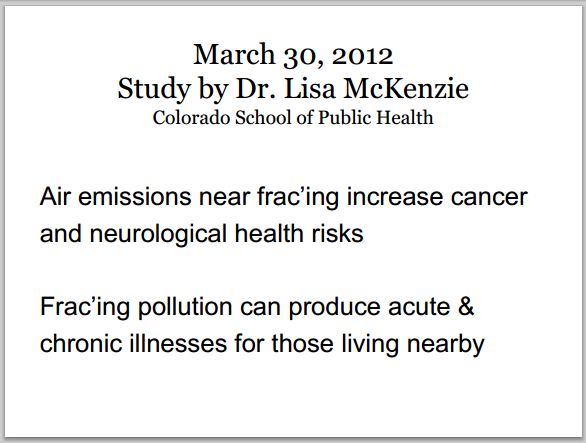

Slide from Ernst presentations