All fracked up: A debut memoir wrestles with toxic masculinity in the oil fields, Michael Patrick F. Smith’s ‘The Good Hand’ offers sharp observations on North Dakota’s extraction industry by Jason Christian, Feb. 17, 2021, High Country News

Courtesy Penguin Randomhouse The Good Hand

Michael Patrick F. Smith

464 pages, hardcover: $29

Viking, 2021

During the Great Recession, one rare economic exception was Williston, North Dakota, in the heart of the Bakken oil patch, where a fracking boom drew thousands of jobseekers. Fast-food joints paid up to $15 an hour, while oilfield hands could earn $200 a day. Prices skyrocketed. The population more than doubled within five years, causing a housing shortage that forced newcomers to sleep in tents, cars or flophouses. Or they piled into trailers corralled together, the notorious “man camps,” a term evoking fistfights, overdoses and sexual abuse. Crime rates soared. The region was overrun.

Set in and around Williston in 2013, Michael Patrick F. Smith’s debut memoir, The Good Hand, critiques the damaging effects of toxic masculinity on women, families and on men themselves, together with the personal, social and environmental costs of oil and gas extraction. In the oil fields, men like Smith perform dangerous, backbreaking labor, but they also enact a kind of relentless white masculine posturing that punishes any sign of difference or weakness. In immersing himself in their world, Smith excavates the devastating masculine tropes in his own family life. In the end, though, he can’t shake his own affection for these damaged, sometimes violent, men, whose respect he craves despite himself.

The Good Hand skillfully braids together scenes of life in Williston — in the oil fields, in the bars, at the three-bedroom townhouse Smith shares with 11 others — with historical dives into the region’s Indigenous and settler-colonial history, and with troubled memories of the terror his abusive father inflicted on his family.

Smith is a musician who cut his teeth on Sam Shepard’s plays and the music of Woody Guthrie and Ramblin’ Jack Elliot. In Brooklyn, his home for several years, Smith worked various gigs to sustain his artistic endeavors as a folksinger, actor and playwright. But he didn’t go to Williston to entertain or to make art. He came to make money as a “swamper,” clocking 15-hour days helping set up and tear down oil rigs. The work turns out to be less about filling his bank account than salving childhood wounds. “My dad never taught me how to do anything,” writes Smith. “He didn’t know how to do much himself. This was part of my obsession with becoming a good hand. I wanted to become a person who knew how to work, who knew how to accomplish tasks, who could get things done.”

In time, Smith does become “a good hand,” a quasi-spiritual concept as he defines it: “A person who does honest work to the best of their ability every day and who offers that work to the world as a living prayer.”

Few people achieve this distinction, in Smith’s estimation. It’s not necessarily the domain of men; Smith’s sister, for example, earns the title as a dedicated nurse. But bound up with his reverence for hard work is Smith’s mythologizing of the men who do it. Smith connects the men he meets on oil rigs to men on battlefields, such as his great-uncles (“true WWII heroes”) and his father, a paratrooper during the Korean War.

“I lusted for that kind of action,” Smith writes, “I thought that if I went through what he went through I would gain not just insight into his life but respect for him, too.” Though working on an oil field is a far cry from facing open combat, Smith finds that during his nine months in the oil patch, he is able to inhabit a counterfactual reality. He follows the road not taken, becoming, like a method actor, one kind of hardworking man.

But assimilation comes with costs. For the first few months, Smith is the butt of every joke. Co-workers threaten to arrange for him to suffer a terrible “accident” after he’s exposed for having voted for Barack Obama. Smith finds himself compromising his values every second of the day, in a world that discourages asking questions about other men’s pasts.

What’s more, he blurs the line between bearing witness to, and becoming complicit in, other men’s disturbing actions. Smith chastises himself for enjoying “the company of unabashed bigots,” remaining mostly silent around “their casual, constant, continuing faucet drip of racism,” including when his landlord lies to a Black family about a room’s availability.

Smith’s eventual attempts to address his own racist complicity are weak, coming long after, and at a safe distance from, the world of oil rigs and rough men: He recalls marching in a Black Lives Matter protest after the police murdered Freddie Gray as a profound experience that leads him to “process the racism in my own heart, born of my own complicity, willful ignorance, and shame.”

But ultimately, it’s a muddled experience. Smith returns to New York calling himself a “loose collection of bad habits.” The romantic trappings the author succumbs to by elevating his newfound, if short-lived, brotherhood above its worst instincts overshadow many of his early critiques of masculine trauma. “Even though I’m not a lifer,” Smith concedes, “all of these men are my tribe.”

Refer also to:

2018: Death in the oilfields, From 2008 through 2017, 1,566 workers perished trying to extract oil and gas in America. About as many U.S. troops died fighting in Afghanistan during that period

Parker Waldridge had worked in the Oklahoma oilfields since he was 16 and acquired the traits that make a good driller: fortitude, intellect and a healthy respect for the power of a runaway gas well.

And so, when Waldridge’s wife, Dianna, heard there had been an accident on a rig he was working near Quinton, in the southeastern corner of the state, last January 22, she tried to stay calm. Parker, an independent contractor hired as a well site consultant, was obsessed with safety and had not once expressed fear about a job during their 34-year marriage, she told herself.

Still, on the four-hour drive to Quinton from their home in Crescent, north of Oklahoma City, dread began to creep in. Dianna had learned before leaving that Parker was among five men missing after an explosion on Patterson Rig 219, operated by Houston-based Patterson-UTI. At a church in Quinton, she sat with her four grown daughters, a son-in-law and the other workers’ families, awaiting confirmation of what everyone there suspected: the men weren’t coming back. They would have to be identified through dental records.

Drilling is an inherently dangerous undertaking, with a fatality rate nearly five times that of all industries in the United States combined in 2014, the last year such rates on oil and gas extraction were published by the government. Production pressures — and the temptation to cut corners — intensify during boom times, as America is experiencing now due to a rush of fossil-fuel exports.

The work of coaxing oil and gas from thousands of feet underground is performed in biting cold and breathtaking heat by stoics like Parker Waldridge, who burned to death at 60 in a driller’s cabin, known as a doghouse, atop the floor of Rig 219.

“It is a macho world,” said Frank Parker, a safety consultant in Magnolia, Texas, who has studied the industry and its workers for more than 50 years. “They get up in the morning and eat nails for breakfast. We need those people to do that kind of work. We’ve just got to find a way not to kill them.”

From 2008 through 2017, 1,566 workers died from injuries in the oil-and-gas drilling industry and related fields, according to data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s almost exactly the number of U.S. troops who were killed in Afghanistan during the same period.

From 2008 through October 25 of this year, the department’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration cited companies in the extraction industry for 10,873 violations, a Center for Public Integrity analysis of OSHA data found. Sixty-four percent of the violations were classified by the agency as “serious,” meaning inspectors found hazards likely to result in “death or serious physical harm.” Another 3 percent were classified as “repeated,” meaning the company previously had been cited for the hazard, or “willful,” indicating “purposeful disregard” for the law or “plain indifference to employee safety.”

During that period, OSHA investigated 552 accidents resulting in the death of at least one worker. Among these were 11 accidents involving Patterson-UTI; OSHA found violations in 10.

Initial penalties in the 552 accidents averaged $16,813, but later were reduced, on average, by 30 percent. (OSHA often cuts fines in exchange for quick settlements and hazard abatement). Some violations are still being contested by employers. Others were dropped by OSHA after negotiations with companies.

The number of workers exposed to death, injury and illness in the upstream portion of the oil and gas industry — exploration and production — is growing, especially in the frenetic Permian Basin of West Texas and southeastern New Mexico. At the beginning of December, according to figures from oilfield services firm Baker Hughes, the basin accounted for more than half of the nation’s operating drilling rigs — 489 in all.

In Texas, oil and gas extraction firms employ 2,400 more people than they did a year ago. But the real job growth has come in support activities: As of October, companies employed 170,600 derrick operators, rotary drill operators and other workers — 50,000 more positions than at the start of the decade. This puts more workers in the path of bone-crushing machinery, explosive gases and cancer-causing chemicals.

Asked how OSHA is responding, a Labor Department spokesman wrote in an email that enforcement crackdowns, centered on the oil and gas industry, are under way in five regions of the country. (The one covering Texas, Oklahoma and New Mexico officially lapsed in October but OSHA inspectors are operating as if it were still in effect, the spokesman wrote.)

Nonetheless, the upstream industry is exempt from key OSHA rules that apply to other industries. It does not have to comply, for example, with the process safety management standard, which requires that refineries, chemical plants and other high-hazard operations adopt procedures to prevent fires, explosions and chemical leaks.

OSHA decided not to include upstream in the original standard in 1992 because it had proposed a rule specifically aimed at drilling. That rule was killed by the White House, whose occupant at the time, George H.W. Bush, had run his own oil company in Texas before entering politics. Unnerved by a catastrophic blast at a Texas fertilizer plant in 2013, then-President Barack Obama ordered OSHA to begin the process of updating the rule. The agency sought, among other things, to bring upstream into the fold.

The response was chilly. The International Association of Drilling Contractors said the removal of the exemption would do “little to improve safety,” impose “unnecessary regulatory burdens and ultimately … result in Americans being put out of work.” The exemption stayed.

David Michaels, who led OSHA at the time, said he met regularly with upstream leaders and they were not universally opposed to more regulation. Still, trade groups such as the American Petroleum Institute argued for the status quo, pointing to the industry’s relatively low injury rate. Michaels didn’t buy it.

“They have a low injury rate because they often don’t report their injuries,” he said in a recent interview. “They have a very high fatality rate, so it’s simply not possible they have a low injury rate.”

In a written statement, institute spokesman Reid Porter said, “API members strictly adhere to OSHA recordable injury reporting and other regulatory reporting requirements.” ![]() Who in their right mind believes what API says?

Who in their right mind believes what API says?![]() He wrote that injury rates within the upstream industry are decreasing and that the process safety management standard “may not apply well to upstream activities.” The Labor Department spokesman did not respond to a question on the standard.

He wrote that injury rates within the upstream industry are decreasing and that the process safety management standard “may not apply well to upstream activities.” The Labor Department spokesman did not respond to a question on the standard.

The numbers, whatever they are, don’t convey the warlike brutality inflicted in the oilfields when something goes wrong. On August 31, 2017, 38-year-old Juan Vicente De La Rosa was working on a platform above a wellhead in Midland County, Texas, when a cable snapped, freeing heavy blocks that struck De La Rosa and killed him almost instantly.

A photograph of the accident scene released by the Midland County Sheriff’s Office under a public-records request shows De La Rosa’s body on the ground, face up. His eyes are shut, his mouth agape. His blue shirt is smeared with what appears to be oil or grease. His left foot is bent outward at a 90-degree angle. His right lower pant leg is shredded.

“I tried CPR but could not get him going,” a co-worker told sheriff’s investigators. “He had a real slow pulse and then none.”

De La Rosa worked for a well-servicing company called Big Lake Services LLC. Big Lake was hired by the owner and operator of the well, Pioneer Natural Resources USA, a major player on the Texas side of the Permian. A lawsuit filed against both firms by the mothers of De La Rosa’s children alleges the Pioneer representative at the site — the “company man,” in industry parlance — acknowledged to investigators “he had been told that the severed cable was in need of repair.”

OSHA cited Big Lake for a single violation and proposed a $12,805 fine, which the company is contesting. It did not cite Pioneer. Pioneer and Big Lake representatives did not respond to requests for comment on the lawsuit; both denied the plaintiffs’ allegations in court filings.

‘This could have been prevented’

Traumatic injuries like those that killed Parker Waldridge and Juan De La Rosa aren’t the only existential hazards upstream workers face. Toxic gases — notably hydrogen sulfide, a component of crude oil that carries a distinctive rotten-egg odor — can be just as lethal.

It was hydrogen sulfide, also known as H2S, that took the life of Gregory Claxton, an Iraq War veteran and the father of a 3-year-old boy, in Montague County, Texas, on February 14, 2015. Claxton, 29, was a crude hauler for Twin Eagle Transport LLC of Houston. Twin Eagle was a contractor for EOG Resources, a large exploration and production company also based in Houston.

Claxton moved oil by truck from a battery of storage tanks at EOG’s Cooper B Unit, near the unincorporated town of Forestburg, to a pipeline in Wichita Falls some 70 miles away. It was part of his job to dip a bottle on a rope, known as a thief, into the tanks to collect a sample so the oil’s consistency, or specific gravity, could be ascertained. (The lighter the oil, the more it is worth). He also was to measure the oil’s depth and temperature to calculate the volume in the tank.

On the morning of his death, Claxton climbed onto a catwalk above a tank holding crude from Well 1H. Opening the hatch, he was hit with a wave of H2S. He died so suddenly that his body was found upright, as if frozen in place. After performing an autopsy, a pathologist with the Dallas County medical examiner’s office listed the cause of death as “Toxic effects of hydrogen sulfide.”

Gregory’s parents, Randall and Shellye Claxton of Nocona, Texas, have settled a lawsuit against Twin Eagle but are still fighting EOG in court. EOG posted no H2S warning signs at the Cooper B Unit, they claim, and Gregory was given no respiratory protection. Had EOG alerted Twin Eagle to the presence of the deadly gas, Shellye believes, Twin Eagle — lacking the proper safety equipment — would have turned down the job.

“He was a Marine,” she said of her son. “He went to Iraq twice. He was willing to lay down his life for his country, and I just don’t want him to have died in vain. I know these accidents happen, but this could have been prevented.”

An EOG spokesman declined to comment; in a court filing, the company denied the allegations in the pending lawsuit. Twin Eagle did not respond to requests for comment but, in a court document, also denied the allegations before reaching a settlement with the Claxtons.

Randall, who was hauling crude for Twin Eagle from a different location the day Gregory died, left the oil business after the accident. Now a long-distance truck driver, he said there is a culture of denial on H2S that extends to the Texas Railroad Commission — which, despite its name, regulates oil and gas drilling in the state. “I’ve got a lot of friends who work in the oilfield,” Randall said. “Every one of them told me there is no H2S in Montague County. They’ve been lied to.”

In an email to the Center for Public Integrity, Railroad Commission spokeswoman Ramona Nye wrote that agency inspectors conducted tests at the Cooper B tank battery on February 19, 2015 — five days after the accident that killed Gregory Claxton. Pulling air into a test tube from a catwalk above the tank Claxton was gauging, the inspectors found “no H2S levels above 2 parts per million,” she wrote, and tests on April 10 of that year picked up no evidence of the gas. Nye added that “there are no H2S-designated fields in Montague County” — that is, no fields with H2S levels of 100 ppm or above. Such designations by the state require operators to provide worker training, post warning signs and implement safety and security measures. ![]() I do not believe her. The Texas “regulator” is about as trustworthy, honest, reliable as AER and Encana – not one bit. Companies are souring sweet formations around the world with their relentless foul greed, injecting mountains of untreated surface water for frac’ing and enhanced oil recovery. Encana lied to its neighbours, volunteer fire fighters and the Rockyford community (neighbouring Rosebud) about one of its sour facilities, posting it as sweet, and selling it as sweet. The life threatening scam was reported to AER, which of course, did nothing but deflect and protect Encana.

I do not believe her. The Texas “regulator” is about as trustworthy, honest, reliable as AER and Encana – not one bit. Companies are souring sweet formations around the world with their relentless foul greed, injecting mountains of untreated surface water for frac’ing and enhanced oil recovery. Encana lied to its neighbours, volunteer fire fighters and the Rockyford community (neighbouring Rosebud) about one of its sour facilities, posting it as sweet, and selling it as sweet. The life threatening scam was reported to AER, which of course, did nothing but deflect and protect Encana.![]()

***

A little H2S reality check:

Sour Gas damages the brain, even at very low levels:

1. Exposure to levels below 10 ppm permanently damage the human brain

2. Harm from levels below 10 ppm by Worksafe Alberta

3. Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) LOW LEVEL HEALTH HARM WARNINGS:

Sour Gas Concentration (ppm)/Symptoms/Effects

0.01-1.5 ppm/Odor threshold (when rotten egg smell is first noticeable to some). …

2-5 ppm/Prolonged exposure may cause nausea, tearing of the eyes, headaches or loss of sleep. Airway problems (bronchial constriction) in some asthma patients.

End a little H2S reality check.

***

Frank Parker, the safety consultant, said that by the time the Railroad Commission did its initial testing on February 19, the hydrogen sulfide levels just beyond the hatch of the tank would have dropped precipitously. “It’s going to disperse within a few minutes” after the hatch is opened, he said.

OSHA says it takes at least 700 ppm of the gas to cause “rapid unconsciousness [and] ‘knockdown’ or immediate collapse within 1 to 2 breaths,” as apparently happened with Claxton. “There’s a great inconsistency between a two-part-per-million hydrogen sulfide reading and somebody dying from acute overexposure,” Parker said. “It does not look to me like the Railroad Commission is trying to find out what really happened.”

In an interview at Shellye and Randall Claxton’s house in November, James York, a family friend and longtime oilfield worker now preparing wells for production in the Permian, called Nye’s statement “bull—-.” York speaks from experience. He recalled working at a tank battery just north of Nocona around 2000 when H2S “pegged my monitor out,” meaning the concentration was at least 100 ppm. He fled.

Why would a regulatory agency insist there was no problem in Montague County?

“They don’t want to document it, because once they document it these companies will have to put procedures in place,” York said. “That will cost them money they don’t want to spend.”

Asked to comment, Nye wrote: “Any operator found to be in violation of RRC rules [governing H2S] faces enforcement action by the Commission.” During the 2018 fiscal year, which ended August 31, the commission took 19 such actions statewide. Ten resulted in collective fines of $47,610; the other nine are pending or were dismissed.

But if a field isn’t designated “sour” — imbued with potentially dangerous levels of the gas — there are no H2S rules to violate.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, documented nine worker deaths nationwide during tank gauging between 2010 and 2014. These were likely due, NIOSH said, not to H2S but to inhalation of hydrocarbon gases or vapors or to asphyxiation by breathing oxygen-depleted air.

The research agency issued alerts in March 2015 and February 2016. The warnings led to an American Petroleum Institute standard urging (but not requiring) operators to find automated ways to measure and sample crude in tanks, so workers wouldn’t have to open the hatches. The Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management adopted a rule along these lines in 2016 for companies drilling on federal lands.

The NIOSH alerts came too late for Gregory Claxton. They might not have helped even if they’d come sooner. And other insidious threats lurk in the oilfields, in part because of the upstream industry’s regulatory exceptionalism. The industry, for example, is exempt from a 1987 OSHA rule designed to strictly limit exposure to benzene![]() which is associated with sperm aneuploidy and U.S. Centers for Disease Control found at dangerous levels in frac workers’ urine

which is associated with sperm aneuploidy and U.S. Centers for Disease Control found at dangerous levels in frac workers’ urine![]() , a highly volatile, carcinogenic component of crude oil. Instead, it is subject to a far more lenient limit, dating to OSHA’s creation in 1971.

, a highly volatile, carcinogenic component of crude oil. Instead, it is subject to a far more lenient limit, dating to OSHA’s creation in 1971.

Benzene is often released during “flowback” operations at well sites in which hydraulic-fracturing fluids and volatile hydrocarbons are collected at the surface and sent to tanks or pits. The OSHA exposure limit for benzene in industries such as oil refining is one part per million averaged over an eight-hour workday. The short-term limit is 5 ppm over any 15-minute period. For upstream companies, the eight-hour ceiling is 10 ppm and there is no short-term limit at all.

In a 2014 paper, NIOSH researchers reported finding benzene spikes above 200 ppm during sampling of flowback operations in Colorado and Wyoming. That’s enough to cause symptoms such as dizziness, headaches, tremors, confusion, rapid or irregular heartbeat and unconsciousness.

Co-author Max Kiefer, now retired, said the spikes suggest the flowback process is not well-controlled and that higher full-shift exposures may be occurring, even though the limited study did not find benzene levels above 1 ppm over a 12-hour workday. If the more restrictive benzene rule applied to the upstream industry, Kiefer said, “It’s likely the industry would have taken action to reduce exposures.” In a statement, API’s Porter wrote that companies had “taken steps since [the NIOSH] findings to mitigate this risk.”

A number of upstream leaders belong to the National Service, Transmission, Exploration & Production Safety Network, a government-industry collaboration that covers 20 oil- and gas-producing states. The network helps spread the word about oilfield hazards such as lung-damaging silica dust, generated by the large-scale use of sand to hold open fissures in underground rock formations during fracking.

In his statement to the Center, the Labor Department spokesman wrote that “OSHA is routinely in touch with employers in the oil and gas industry to improve health and safety.” He pointed to a safety conference in Houston, co-sponsored by the department, that drew about 1,200 people in early December.

In Shellye Claxton’s view, however, there is no substitute for the strict policing of companies bent on making as much money as quickly as possible.

“There are little things they can do” to enhance safety, she said, “but they don’t want to spend the extra dollars.”

‘Rogue corporate entity’

At 6 a.m. on January 22, Parker Waldridge reported for work at well 1H-9 on the Pryor Trust 0718 gas lease in Pittsburg County, Oklahoma. As is typical, a tangle of companies was involved in the drilling of the L-shaped well, which had reached 13,435 feet. The lease holder was Red Mountain Energy LLC; the well operator, Red Mountain Operating LLC. The latter hired Patterson-UTI as the drilling contractor. Waldridge, an independent contractor, was working for a project-management firm called Crescent Consulting LLC.

Within hours of Waldridge’s arrival on site, he and four others would be dead, burned beyond recognition in the 1H-9 doghouse. It was the deadliest drilling accident in the U.S. since the Deepwater Horizon rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, killing 11 workers.

A fact sheet issued by the U.S. Chemical Safety Board, which is investigating the Pryor Trust blowout, presents the following timeline:

At 6:48 p.m. on January 21, the Patterson-UTI crew began removing drill pipe from the well bore — an operation known as “tripping” — so the drill bit could be changed. A heavy fluid known as drilling mud was pumped into the well to fill the void created by the removal of the pipe. Shortly after midnight, the crew pumped a weighted cap known as a “pill” — consisting of a claylike mineral called barite and meant to keep gas from invading the well and creating a blowout risk — to about 7,000 feet, near the bend in the “L.”

The tripping operation resumed, and by 6:10 a.m. on the 22nd as Waldridge’s shift began, the crew had removed the drill bit and other components from the bottom of the hole.

Unbeknownst to the workers, gas had, in fact, entered the well during tripping. The well was equipped with a blowout preventer, but key parts of that device — blocks of steel known as “blind rams” — did not fully close. A towering, hissing fire erupted at 8:36 a.m. and was not extinguished until 4 p.m.

After an investigation, OSHA cited Patterson-UTI in July for six violations and proposed fines totaling $73,909; Patterson is contesting the citations. The agency cited Crescent Consulting for four violations and proposed fines totaling $36,586. It, too, is contesting. No citations were issued to either Red Mountain Energy or Red Mountain Operating.

Meanwhile, Parker Waldridge’s wife, Dianna, has filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against Patterson-UTI, Red Mountain Energy, Red Mountain Operating, Crescent Consulting and mud-supplier National Oilwell Varco LP. The lawsuit calls Patterson a “rogue corporate entity” and accuses it of “a cascade of errors and multiple departures from safe drilling practices,” including failing to take countermeasures against “underbalanced” tripping, when pressure in the hole is greater than it is on the surface. This can allow gas to migrate into the vertical section of the well.

The lawsuit cites deposition testimony from Patterson-UTI employees and internal company documents showing that the day crew on January 22 inherited “a ticking time bomb.” Documents show, for example, that the machine that operated the balky blind rams on the well’s blowout preventer “was improperly maintained and in a state of severe disrepair,” the lawsuit says. It adds that an email warning to this effect — with a skull-and-crossbones graphic — was sent at least two days before the blowout to the Patterson-UTI rig manager and superintendent. The former testified that he never saw the email but agreed it “should have been taken seriously,” and the latter “did not remember if he looked at it.”

Patterson-UTI is one of the biggest drilling operators in the country, accounting for 15 percent of the active rigs in the U.S. as of late November. Its corporate culture was laid bare three years ago, when it settled a discrimination case with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for $14.5 million.

A lawsuit brought against Patterson-UTI by the EEOC on behalf of some 1,000 employees alleged the company “engaged in a nationwide pattern or practice of discrimination based on race and national origin on its drilling rigs,” assigning minority workers to the lowest-level jobs and disciplining, demoting or firing them disproportionately. Depositions associated with that lawsuit paint a grim picture of the work environment for people of color; one Native American driller, who kept a diary, testified that a supervisor regularly called him a “f—— Indian” and asked if he was “drunk” or “high.”

The Waldridge lawsuit accuses the company of having “the second worst worker fatality rate among its peers in the industry,” accounting for the deaths of at least 50 workers since 1999.

In a written statement, Patterson-UTI said that “while we have no intention of litigating this in the press, it is important to note that Red Mountain was the lease holder and operator of the well, which was drilled under its direction, supervision and control. Red Mountain was also responsible for the well’s design and drilling program.” The company said it disagrees with OSHA’s findings and the “gross mischaracterizations” in the lawsuit and has “dramatically reduced workplace incident rates and significantly increased overall employee safety” in recent years.

Of the EEOC case, the company said, “Rather than pursuing costly litigation to dispute past claims, Patterson-UTI chose to work with the EEOC to institute additional human resources best practices and to enter into a no-fault settlement …. The Company is committed to providing a work environment for all employees that is inclusive, respectful and supportive.”

A spokeswoman for Red Mountain Energy issued the following statement on behalf of company president Tony Say: “Safe, responsible operations are the top priority at every Red Mountain Energy well. Our deepest sympathies go out to those affected by this tragedy. We are confident the legal process will exonerate our company.” ![]() I am too, and not because the company is innocent.

I am too, and not because the company is innocent.![]()

A Crescent Consulting official did not respond to requests for comment, though the company denied responsibility for the accident in court pleadings. A spokesman for National Oilwell Varco wrote in an email that the firm “denies all liability concerning the tragedy that occurred [on] Patterson Rig #219.”

During a recent interview in Oklahoma City, Dianna Waldridge and one of her lawyers, Michael Lyons of Dallas, spoke at length about the Pryor Trust accident and its aftermath. Lyons said there was “a climate and a culture” of carelessness at Patterson-UTI, which made “terrible mistakes” on Rig 219.

“It all starts in a boardroom many miles away,” he said. “I don’t blame the men who, unfortunately, died in this tragedy or were out there working. It’s not their fault they were improperly trained and improperly supervised.”

Dianna, who still works cattle and grows wheat on the 320-acre ranch she and her husband bought a quarter-century ago, struggled to maintain her composure during the interview.

“I’ve lost the man that I love, that I wanted to grow old with,” she said, her voice halting. “Not having him will affect me forever.”

The anguish caused by the Pryor Trust blowout extends beyond the dead workers’ families. In a September deposition for the Waldridge case, Sheriff Timothy Turner of Haskell County, Oklahoma — which adjoins Pittsburg County and is home to many oilfield workers — testified that the accident is a frequent topic of conversation among residents of southeastern Oklahoma.

“Every time there’s an incident with a Patterson rig now, it’s ‘Patterson killed those guys.’ … They believe that the person who oversaw that rig should be in jail,” Turner said.

“He murdered five people. That’s their belief.” ![]() Mine too.

Mine too.![]()

***

To balance some of that toxic masculinity, Andrew Nikiforuk’s Slick Water:

2016: Note to Ernst’s ex legal team from citizen in Missouri

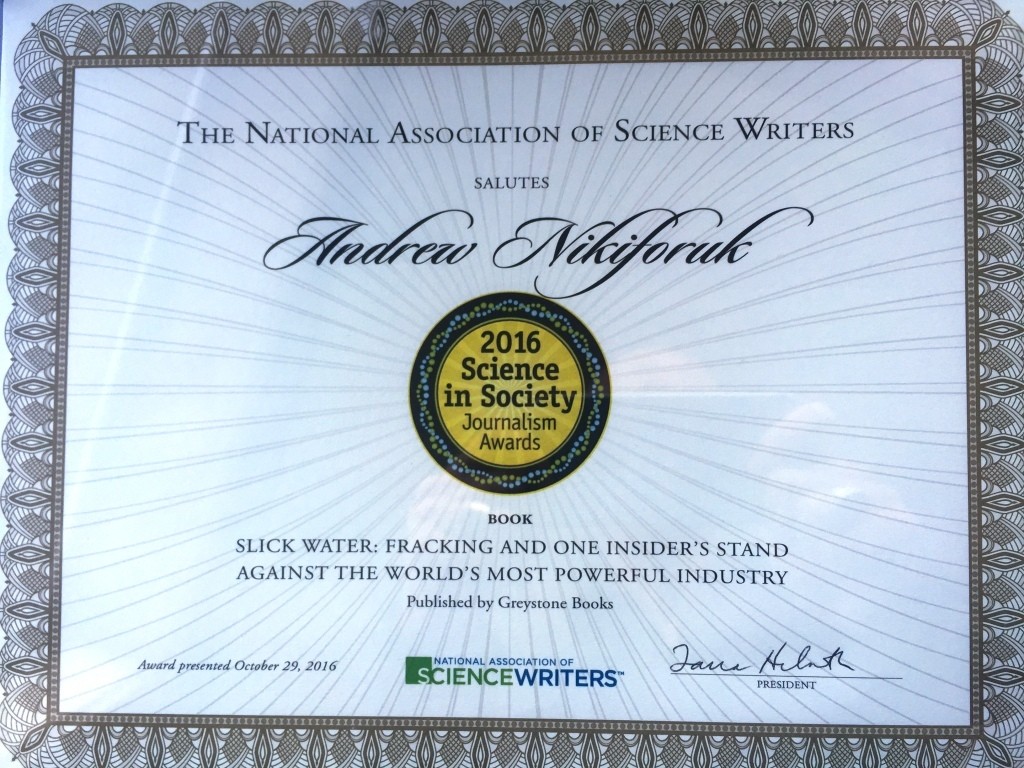

Mr. Nikiforuk’s acceptance speech:

To San Antonio/National Association of Science Writers

Thank you for this great honor and for inviting me to San Antonio.

In Canada it would be difficult to fill a bus full of science writers—it is reassuring that you can still fill a entire ballroom here in the United States.

The founder of Pakistan once said that there are two powers in the world; one is the sword and other is the pen. But that there is a third power stronger than both, that of women.

So I would like to thank first my Hebredian wife, Doreen Docherty for her continued support and in making my writing possible.

Second, I’d to thank the other woman in my life: Jessica Ernst. She is a scientist and she has worked in Alberta’s oil patch for 20 years. It took her nearly a decade to trust me with her story. Prickly. Fiercely brilliant. Combative. Wedded to evidence. Uncompromising. Meticulous. Pain in the ass. That’s Ernst.

As such Slick Water is really a story about the courage of women—and that courage differs from that of men: it is civil, persistent, strategic and selfless.

Ernst’s story is dramatic. During a messy resource boom Encana, then one of her clients, fracked into a shallow aquifer in her community near Calgary, Alberta and clearly broke the law. Ernst then caught regulators behaving badly and covering up the deed. She has now spent 9 years pursuing justice and accountability in Canada’s byzantine court system.

So I want to thank the Science In Society judges in particular for recognizing her courage and strength of character. Such people can and do change the world.

Let me add a word on the dysfunctional technology of hydraulic fracturing. Politicians and the media often portray more technology as solutions to our problems. But as many science writers know, the thoughtless deployment of previous technologies has multiplied our problems. We have a word for this predicament: complexity.

Industry swore that its cracking rock technology was safe and proven, but science now tells a different story. Brute force combined with ignorance (and that’s how one executive described the technology) has authored thousands of earthquakes from British Columbia to Texas. It has called forth clouds of migrating methane in the Four Corner states. The science is complicated but clear: cracking rock with fluids is a chaotic activity and no computer model can predict where those fractures will go. The regulatory record shows that they often go out of zone; extend into water; and rattle existing oil and gas wells, and these rattled wells are leaking more methane.

The French philosopher Jacques Ellul spoke eloquently about technology and its increasingly dominant role in our lives decades ago. He thought that whenever we abdicate our responsibilities to uphold truly human values and whenever we limit ourselves to leading a trivial existence in a technological society with the sole objective of adapting to more technologies and material comforts, we turn our backs on justice and the human spirit.

My deep thanks to the National Association of Science Writers for shining a light on that spirit tonight.