Preliminary Field Studies on Worker Exposures to Volatile Chemicals during Oil and Gas Extraction Flowback and Production Testing Operations by Eric J. Esswein, MSPH, CIH, John Snawder, PhD, DABT, Bradley King, MPH, CIH, Michael Breitenstein, BS, and Marissa Alexander-Scott, DVM, MS, MPH, August 21, 2014, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

This blog describes NIOSH evaluations of worker exposures to specific chemicals during oil and gas extraction flowback and production testing activities. These activities occur after well stimulation and are necessary to bring the well into production. Included are descriptions of initial exposure assessments, findings, and recommendations to reduce worker exposures to potential hazards. Further details about these assessments can be read in a recently published peer-reviewed journal article, “Evaluation of Some Potential Chemical Exposure Risks during Flowback Operations in Unconventional Oil and Gas Extraction: Preliminary Results”.[i]

Flowback refers to process fluids that return from the well bore and are collected on the surface after hydraulic fracturing. In addition to the mixture originally injected, returning process fluids can contain a number of naturally occurring materials originating from within the earth, including hydrocarbons such as benzene. After separation, flowback fluids are typically stored temporarily in tanks or surface impoundments (lined pits, ponds) and recovered oil is pumped to production tanks, which are fixed systems at the well pad.

NIOSH exposure assessments included short-term and full-shift personal breathing zone and area air sampling for exposures to benzene and other hydrocarbons using standard methods and analyses listed in the NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods.[ii] Real-time, direct reading instruments were also used to characterize peak and short-term exposures to workers and various workplace areas for volatile organic compounds, benzene, carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide, and flammable/explosive atmospheres. We conducted biological monitoring by collecting pre- and post-shift urine samples from flowback workers to evaluate exposure to benzene. Benzene metabolites found in a worker’s urine indicate some level of exposure during the work shift. Benzene is an exposure concern because the Department of Health and Human Services’ National Toxicology Program has determined that it is a known carcinogen (i.e., can cause cancer).[iii] The International Agency for Cancer Research and the EPA have also determined that benzene is carcinogenic to humans.[iv,v]

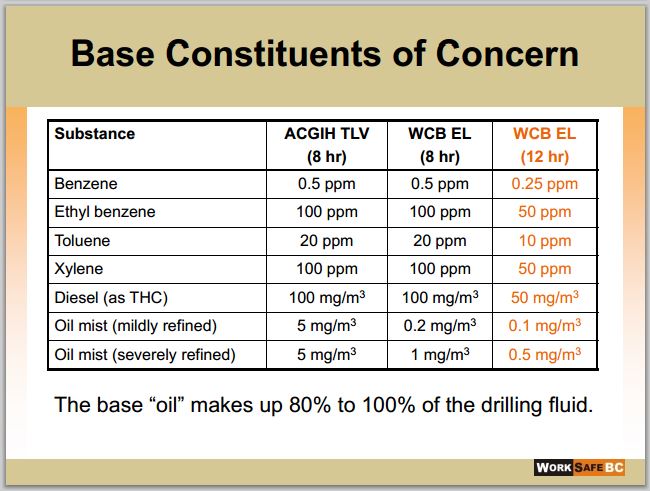

Workers gauging tanks can be exposed to higher than recommended levels of benzene. The average full-shift time-weighted average (TWA) personal breathing zone benzene exposure (± 1 standard deviation) for workers gauging flowback or production tanks (n=17) was 0.25 ± 0.16 parts per million (ppm). Fifteen of these 17 samples exceeded the NIOSH recommended exposure limit (REL) of 0.1 ppm (0.32 mg/m3)[vi]. (This REL is a quantitative value based primarily on analytical limits of detection. NIOSH recommends that occupational exposures to carcinogens be limited to the lowest feasible concentration). Because the flowback technicians’ work shifts were 12 hours, a reduction factor of 0.5 was calculated to modify the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) threshold limit value for benzene from 0.5 ppm to 0.25 ppm. Two of 17 samples met or exceeded the ACGIH unadjusted value of 0.5 ppm value; six of 17 exceeded the adjusted value of 0.25 ppm.[vii] Task-based personal breathing zone samples for benzene collected during tank gauging on flowback tanks exceeded the NIOSH short-term exposure limit (STEL) for benzene (1 ppm as a 15-minute TWA).[ii] At several sites, direct-reading instrumentation measurements detected peak benzene concentrations at open hatches exceeding 200 ppm.

The average full-shift personal breathing zone benzene exposures (± 1 standard deviation) for workers not gauging tanks (n=18) was 0.04 ± 0.03 ppm. The difference in mean personal breathing zone benzene exposures between those who gauged tanks and those who did not was statistically significant. Seventeen of the 18 samples were below the REL as a full-shift TWA for those not gauging tanks. None of the 35 full-shift personal breathing zone sampling results exceeded the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) permissible exposure limit for benzene of 1 ppm for general industry (29 CFR 1910.1028External Web Site Icon) or 10 ppm for the oil and gas drilling, production, and servicing operations sector exempt from the benzene standard (29 CFR 1910.1000 Table Z-2External Web Site Icon).[viii] Exposures to other measured hydrocarbons (e.g., toluene, ethyl benzene, and xylenes) did not exceed any established occupational exposure limits.

For the biological monitoring, we used s-phenyl mercapturic acid, a specific metabolite of benzene that can be measured in urine. We compared the results to the ACGIH Biological Exposure Index (BEI) for occupational benzene exposure.[iii] The benzene BEI represents the concentration of metabolites most likely to be observed in specimens collected from healthy workers exposed to the ACGIH TLV of 0.5 ppm. None of the biological monitoring samples were found to exceed the ACGIH BEI.

Direct reading instruments identified instances of short-term flammable atmosphere measurements as high as 40% of the lower explosive limit (LEL) adjacent to separators and flowback tanks; in general, a concentration of 10–20% of the LEL is considered a risk for fires and is the typical alarm settings for direct reading personal and fixed flammable gas monitors.

Preliminary Conclusions

These findings suggest that benzene exposure can exceed the NIOSH REL and STEL and present an occupational exposure risk during certain flowback work activities. Based on these preliminary studies, primary point sources of worker exposures to hydrocarbon vapor emissions are opening thief hatches and gauging tanks; additional exposures may occur due to fugitive emissions from equipment in other areas in the flowback process (e.g., chokes, separators, piping, and valves), particularly while performing maintenance on these items. The NIOSH research found that airborne concentrations of hydrocarbons, in general, and benzene, specifically, varied considerably during flowback and can be unpredictable, indicating that a conservative approach to protecting workers from exposure is warranted. Hydrocarbon emissions during flowback operations also showed the potential to generate flammable and explosive concentrations depending on time and where measurements were made, and the volume of hydrocarbon emissions produced.

Recommendations for Protecting Workers

Based on workplace observations at the sites visited, NIOSH researchers identified a number of general recommendations to reduce the potential for occupational exposure:

Develop alternative tank gauging procedures so workers do not have to routinely open hatches on the tops of the tanks and manually gauge the level of liquid.

Develop dedicated sampling ports, other than the thief hatches, that minimize workers’ exposures to volatile organic compound emissions while manually tank gauging.

Provide worker training to ensure flowback technicians understand the hazards of exposure to benzene and other hydrocarbons and the importance of monitoring atmospheric conditions for LEL concentrations.

Limit the time spent in proximity to hydrocarbon sources. [What are harmed families to do, forced against their will (and often fed lies about how “perfectly safe” the industry is), to live with frac pollution in their homes and businesses?]

Monitor workers to determine their exposure to benzene and other contaminants.

Establish a controlled perimeter (similar to the high pressure zone established during hydraulic fracturing) around flowback tanks. Limit entry and require that any portable tents or sunshades remain outside and upwind of the controlled area.

Provide workers with calibrated portable flammable gas monitors with alarms at appropriate levels. The actions to be taken if the alarm sounds should be defined before the detector system is put into use.

Use appropriate respiratory protection in areas where potentially high concentrations of hydrocarbons can occur as an interim measure until engineering controls are implemented. Note that OSHA regulations (29 CFR 1910.134External Web Site Icon) require a comprehensive respiratory protection program be established when respirators are used in the workplace.4

Use appropriate impermeable gloves to protect against dermal exposures during work around flowback and production tanks and when transferring process fluids.

New study shows gas workers could be exposed to dangerous levels of benzene by Susan Phillips, August 28, 2014, State Impact

A new study out this month reveals unconventional oil and natural gas workers could be exposed to dangerous levels of benzene, putting them at a higher risk for blood cancers like leukemia. Benzene is a known carcinogen that is present in fracking flowback water. It’s also found in gasoline, cigarette smoke and in chemical manufacturing. As a known carcinogen, benzene exposures in the workplace are limited by federal regulations under OSHA. But some oil and gas production activities are exempt from those standards.

The National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety (NIOSH) worked with industry to measure chemical exposures of workers who monitor flowback fluid at well sites in Colorado and Wyoming. A summary of the peer-reviewed article was published online this month on a CDC website. In several cases benzene exposures were found to be above safe levels.

The study is unusual in that it did not simply rely on air samples. The researchers also took urine samples from workers, linking the exposure to absorption of the toxin in their bodies. One of the limits of the study includes the small sample size, only six sites in two states.

Dr. Bernard Goldstein from the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health says the study is the first of its kind. Goldstein did not contribute to the study’s research, but he has conducted his own research on benzene. And he’s treated patients exposed to the carcinogen.

“These workers are at higher risk for leukemia,” said Goldstein. “The longer, the more frequently they do this, the more likely they are to get leukemia particularly if the levels are high.”

The study looked at workers who use a gauge to measure the amount of flowback water that returns after a frack job is initiated. A spokeswoman for NIOSH says none of their studies draw any conclusions about exposures to nearby residents, but focus specifically on workers.

But Dr. Goldstein says it shows that there could be potential risks to residents as well.

“We’re not acting in a way to protect the public who are at high risk,” said Goldstein.

… A spokeswoman for an industry group says there is always room for improvement if toxic exposures exist.

“[The study represents] a small sample size,” said Katie Brown with the group Energy In Depth. “It is limited in that respect. I think that’s the whole reason for this partnership is to study it and see how [drillers] can improve.”

Authors of the NIOSH benzene study said that more research with larger sample sizes should be done, especially since there was so much variation in the levels observed at different times and well sites. The researchers also listed a number of recommendations for industry to take to reduce benzene levels on the job site. These include changing tank gauging procedures, training workers, limiting exposure times, carrying gas monitors, using respiratory and hand protection, and monitoring exposure levels. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to:

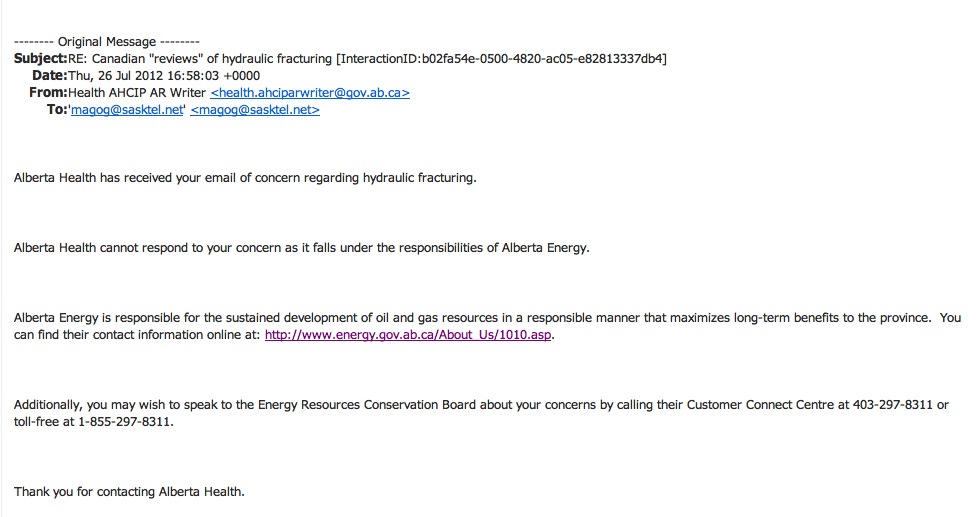

Alberta Health deflects Ernst’s concerns about health harm from fracing, and recommends she contact the “no duty of care” regulator and “no duty of care” Alberta government:

Frac’ing could threaten air quality, workers’ and public health, University of Maryland report says

THE SHALE GAS REVOLUTION FROM THE VIEWPOINT OF A FORMER INDUSTRY INSIDER

Four Fatalities Linked to Used Fracking Fluid Exposure During ‘Flowback,’ NIOSH Reports

B.C. horse breeder recounts fracking sour gas leak scare caused by Encana

Imperial Oil wants Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench to dismiss Bilozer lawsuit over pollution claim

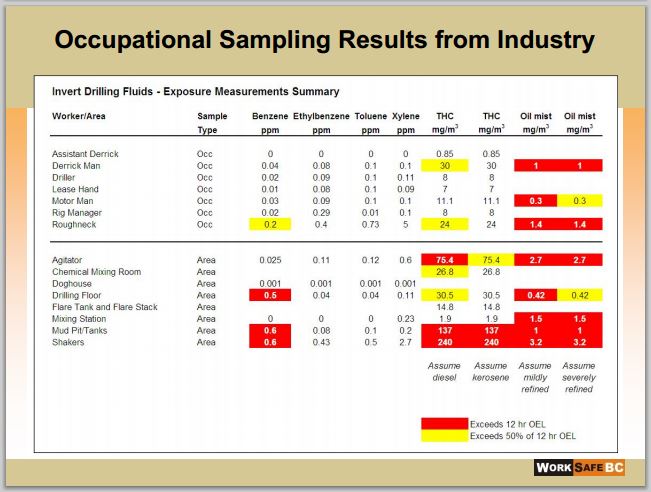

Slides below from presentation by Geoffrey A. Clark and Colin Murray WorkSafeBC: