40,000+ cubic metres water gone permanently in ONE frac’

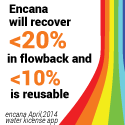

Based on 2014 data, Encana will recover less than 20% of water in frac flow back with less than 10% reusable (likely even less than that, as cleaning up toxic radioactive frac waste water before it can be reused costs money, lots and lots of money.

A proportion (25% to 100%) of the water used in hydraulic fracturing is not recovered, and consequently this water is lost permanently to re-use, which differs from some other water uses in which water can be recovered and processed for re-use.

64% of Alberta wetlands no longer exist

Images above made by Barb Ryan of Frac Central Fox Creek, Alberta, a few years ago. More wetlands have been bulldozed over or dried up by now, thanks to human idiocy and greed.

BC is permitting the same frac insanity as Alberta is, and Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, etc.

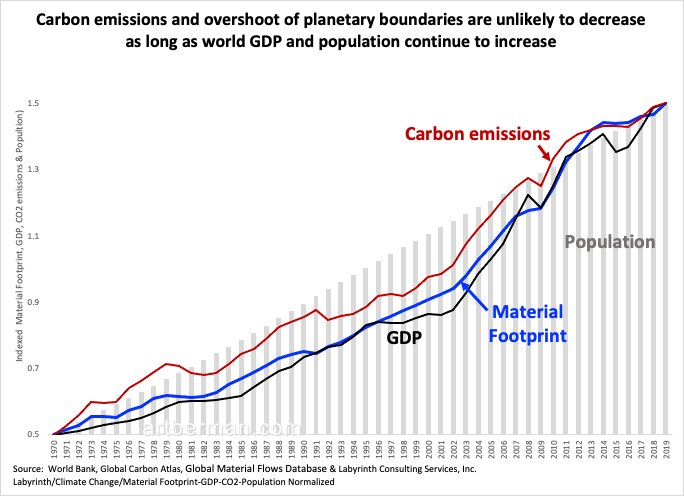

This graph sums up human greed and stupidity best (“net zero” fixes nothing when humans suck earth dry):

Draining the World of Fresh Water, Two recent studies show human activity is drying up the planet’s lakes, rivers and aquifers by Andrew Nikiforuk, April 11, 2024, The Tyee

“When you drink the water, remember the spring.”

— Ancient Chinese proverb

The thirst of humans and our technology for water, according to two important studies, is bottomless and accelerating, even if the precious liquid itself is finite on this planet.

One study shows that human activity has massively altered the world’s flow of surface water and imperilled water cycles critical for life as varied as fish and forests.

The other confirms that in many places on Earth aquifers and groundwater wells are being pumped and mined faster than they can be replenished.

The concept of the technosphere helps to explain the forces in play. U.S. geologist Peter Haff has described the technosphere as a parasitic offshoot of the living Earth, or biosphere. This largely autonomous force, committed to endless consumption![]() which demands ever escalating human baby-making

which demands ever escalating human baby-making![]() , wields a “matrix of technology” that directs the flows of energy, materials, water and waste across the globe. It leaves in its wake enormous streams of pollution: plastic, carbon dioxide, nitrogen and the foulest of water.

, wields a “matrix of technology” that directs the flows of energy, materials, water and waste across the globe. It leaves in its wake enormous streams of pollution: plastic, carbon dioxide, nitrogen and the foulest of water.

Haff observes that “humans have become entrained within the matrix of technology and are now borne along by a supervening dynamics from which they cannot simultaneously escape and survive.”![]() Which is why I think our species is stupid

Which is why I think our species is stupid![]()

But the technosphere grinds on, damming, pumping, mining, harvesting and supporting all manner of artificial environments supposedly on behalf of the world’s eight billion people, who remain largely blind to the vast amounts of water needed to sustain it all. The technosphere respects no limits and unlike previous civilizations holds nothing sacred — not even a mountain watershed.

Before the technosphere began its conquest of the biosphere, surface water and groundwater worked together in one of the world’s most remarkable and faithful marriages.

One is visible in the form of gurgling streams, undulating rivers and lively marshes. The other is invisible yet connected to them all. Surface waters replenish subterranean waters and vice versa. When a civilization abuses one, it trashes the other. Drain the Ogallala Aquifer, for instance, and parts of the Arkansas River simply dry up.

And that’s what these two recent studies clearly document.

Upsetting the freshwater cycle

All life depends on the flow of water. The first study by Finnish researchers used some sophisticated modelling to show changes over time. They found that over a 145-year industrial period, the technosphere and its growing population have dramatically shifted streamflow and soil moisture compared with a pre-industrial baseline (1661-1860). In other words, human pressure on natural water flows turned a fairly stable system into a fragile one.

It has done so with dams (only one-third of the world’s rivers remain free flowing), deforestation, irrigation, city-making and “intensification and homogenization of global water cycle.” As a result, the world is experiencing increases in the severity, frequency and duration of floods and droughts.

Changes in streamflow and soil moisture started to steadily increase after the end of the pre-industrial period and surpassed the upper bounds of pre-industrial variability by the early 20th century.

The Mississippi, Indus and Nile basins, for instance, were among the first regions to show “persistent transgressions” in streamflow variability due to human engineering. Changes in soil moisture occurred in fewer regions and often later than in the case of streamflow, and were most notable in Siberia, South and Southeast Asia and the Congo Basin.

The intensity of irrigation corresponded “with increasing dry streamflow and wet soil moisture deviation frequency” in places such as South Asia, eastern China, the western United States and the Nile Delta. The Aral Sea in Central Asia, formerly the world’s third-largest lake, tells a familiar water parable: the overuse of water for irrigation to grow cotton depleted a great lake, devastated local fisheries, pummelled biodiversity and bred dust storms.

Dramatic shifts in streamflow and soil moisture (the amount of water available for plants) have also resulted in agricultural productivity shocks in South and East Asia, Australia and North Africa.

In sum, the land area experiencing streamflow and soil moisture changes from pre-industrial times has increased by 78 to 94 per cent and 42 to 61 per cent, respectively, over the last 145 years.

The Finnish researchers concluded with an obvious warning. “Committing to ambitious climate action, halting deforestation and respecting environmental flows in water use and management is thus imperative to safeguard the life-supporting functions of freshwater.”![]() Most vital mitigation though, and most never say it: humans need to stop being so fucking selfish, and quit making so many kids; rape religions, political parties and their religion-run courts need to lose their power forcing birth on raped and or unwilling women and girls.

Most vital mitigation though, and most never say it: humans need to stop being so fucking selfish, and quit making so many kids; rape religions, political parties and their religion-run courts need to lose their power forcing birth on raped and or unwilling women and girls.![]()

A logical question follows: Will the technosphere, a leviathan humans have created but don’t consciously guide, allow such a shrinkage of its insatiable ambitions?

The empty wells

Groundwater fills subterranean cracks and gaps in rocks and sediments with fresh water. It accounts for around 30 per cent of all readily available fresh water in the world. About 10 million Canadians depend on it for their drinking water.

A group of researchers from the University of California, Santa Barbara, spent three years collecting and analyzing data on some 1,700 aquifers around the world. That’s how long it took “to make sense of 300 million water level measurements from 1.5 million wells over the past 100 years.”

The researchers found that groundwater is dropping in 71 per cent of the studied aquifers. (Much of the world has little data on groundwater depletion.)

The rate of decline is accelerating the fastest in many arid regions including Southern California, the Great Plains, Saudi Arabia, northern China, Iran and Chile. (Separate studies show that about 45 per cent of 80,000 groundwater wells in the United States show persistent declines since 1940.)

Groundwater levels have dropped by one metre in central Alberta and Saskatchewan too.

The acceleration in groundwater depletion has sped up in the last 20 years compared with rates recorded in the 1980s and 1990s. The worst declines are all taking place in semi-arid geographies transformed by irrigation.

Alberta’s Brutal Water Reckoning

The climate crisis has played a significant role. Depletions in about 90 per cent of aquifers occurred in geographies that have gotten drier over the last 40 years. Global heating causes more surface water to evaporate before it has a chance to seep into the ground and replenish aquifers. Climate change, as recent Tyee articles have noted, also shrinks snowpacks.

Perhaps prompted to provide a word of optimism, the researchers duly emphasized that aquifers have been recharged in a few instances. But in most cases the water didn’t come from conservation but from another water basin. Peter was robbed to pay Paul.

The implications of groundwater extraction are straightforward. Places like Kansas that depend on groundwater for industrial farming will record their smallest wheat production this year since the 1960s. Wherever aquifers have been drained, sinkholes appear, the land subsides and streams and rivers dry up.

What the two studies are telling us is this: water usage by the technosphere has damaged the global water cycle and is now outstripping groundwater capacity. Water and food security are at risk.

One of the key drivers of this water crisis, although not explicitly mentioned in the papers, has been the Jevons paradox. Whenever technologies make the consumption of a resource more efficient, little or no savings are realized because of increased consumption.

Efficient irrigation systems have not conserved water but encouraged the expansion of irrigated land and related technologies, resulting in increased water spending around the world. In northern China, for example, highly efficient water systems have resulted in not a decrease but an increase in water consumption.

With global temperatures poised to rise beyond 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels, the movement of water around the planet will become ever more variable and unreliable.

The more technology cannibalizes the biosphere and tries to manage or commandeer its water flows for the benefit of one species, the more extreme, unpredictable and variable water flows will become.

Our ancestors, who possessed imaginations and lived in a biosphere, had names for monsters: Minotaur, Leviathan, Moloch, Jorogumo, Hydra and Lamashtu.

What name would befit the ever-thirsty technosphere, the mechanical dragon changing the journey of the world’s fresh waters?

Water is in short supply in southern Alberta. Is a massive expansion of irrigation possible? Canada’s biggest irrigation district says farmers will get half the amount they get in a good year by Joel Dryden and Carla Turner, CBC News · Posted: Apr 09, 2024 7:00 AM CDT | Last Updated: 11 hours ago

At an annual general meeting in Lethbridge for the largest irrigation district in Canada, it’s standing room only.

These AGMs for the St. Mary River Irrigation District, located in southern Alberta, are normally sleepy affairs. But this year is different as the province is staring down challenging drought conditions.

What’s expected today is big news for the 200-odd people filing into the room, some wearing jackets bearing the names of their respective operations.

Grant Hunter, United Conservative Party MLA for Taber-Warner, takes a seat in the crowd.

As organizers react to a growing line curling around the corner, event staff clear out removable walls and roll in more chairs.

Still, it’s not enough, and soon, people are leaning on walls at the back of the room. Two farmers slide up and park themselves on a table.

Those who have gathered here are well aware of the difficulties looming over the coming farm year.

The district, responsible for delivering irrigation water to farmers in southern Alberta, launches a PowerPoint presentation to lay out the challenges ahead. An organizer makes a joke about being run out the door by unhappy attendees.

Semi-arid southern Alberta, which relies heavily on irrigation, is expected to be hit with particular challenges — and new data from Environment and Climate Change Canada paints a striking picture of Canada’s Prairies.

The brown area in the photo is very concerning because it means virtually zero to no snowpack in an expanse that extends across the Prairies, said Tricia Stadnyk, a professor and Canada Research Chair in hydrologic modelling with the University of Calgary’s Schulich School of Engineering.

“It’s highly unlikely that we can avoid drought at this point. Because without the snowpack, we don’t have the soil moisture, which means that the ground is dry,” she said.

“That’s going to have a significant impact on agriculture.”

The main event

In the room at the St. Mary River Irrigation District AGM, organizers explain that supply in the area is lower compared with last year, with a dry winter affecting snowpack and reservoir storage. El-Niño-type activity indicates drier and warmer weather ahead.

But the crowd clearly is anxious to learn about one big decision. Around an hour into the meeting, speakers arrive at the main event.

“Before I let you go for coffee, I know what you’ve been waiting for,” said George Lohues, chairman of the district.

Farmers lean forward in their chairs, and the room grows tense.

The district had previously communicated it was possible farmers would be allotted around eight inches of water at the gate — meaning irrigators within the district could use up to eight inches of water per acre for their registered parcels. In a good year, that number is set at 16.

There had been a chance that recent snowfalls would have allowed for an increase in that number. But it’s not to be.

It’ll be eight inches for now. Half of a good year.

And though it will have a significant impact on operations, the room registers the information quietly, and accepts it. It’s no big surprise. They break for coffee and head to the hallways.

David Westwood, general manager of the St. Mary River Irrigation District, explains what has led to the decision.

The district uses forecasts from Alberta Agriculture and Irrigation, pulling together data on storage, snowpack, historical precipitation and irrigated acreage across multiple districts to calculate an estimate for water allocation.

“We wanted to make sure we set an allocation that we feel we could service throughout the season, but obviously not run short of water,” Westwood said.

Michel Camps is one of the farmers who came to the meeting. He had hoped the district would settle on nine or 10 inches. But he understands what led to where they are now.

“These guys don’t set allocations lightly … but they can’t forecast the future. So they gotta go about what they know,” Camps said.

A big impact

His operation, CP Farms, is 30 kilometres east of Lethbridge. He runs it with his wife, Hanneke.

The farm prioritizes potato production above all else, tailoring its operations, rotations and equipment purchases accordingly. Potatoes receive precedence in tasks such as spraying and planting.

What led Camps to potato farming?

“Well, how much time do you have?” he said.

Camps and Hanneke, immigrants from Holland, bought what was at that time a 250-acre potato farm with a substantial bank loan and family funds. Camps’ upbringing in Holland, where his family farm also cultivated potatoes, influenced their focus in Canada.

“We had no idea that the potato industry [in Canada was] gonna balloon to what it is today,” Camps says. Today, 80 per cent of the farm’s potato production — 1,600 acres — goes to the McCain Foods plant, located just down the road.

Irrigation is crucial for this operation. The majority of the crops grown require much more water than what usually comes through natural rainfall in southern Alberta. If the water doesn’t come, CP Farms might as well not grow its crops.

The water allocation set by the St. Mary River Irrigation District is usually not a big deal. But the eight inches presents a new challenge for CP Farms — a challenge this part of the province hasn’t had to deal with since 2001.

Camps said he’ll reallocate water from grain to his high-value crops. Crop insurance requires watering of grains to four inches, so he’ll need to do that before redirecting the rest to the more lucrative potato crops.

The difference between eight and 16 inches on his farm will mean a difference in millions of dollars of revenue.![]() Humans need to stop focusing so much on money and attacking womens’ rights (notably reproductive), and start focusing on reducing stupid practices like frac’ing, enchanced oil recovery, tarsands mining and SAGD, and reducing population, pollution, greed, and selfishness.

Humans need to stop focusing so much on money and attacking womens’ rights (notably reproductive), and start focusing on reducing stupid practices like frac’ing, enchanced oil recovery, tarsands mining and SAGD, and reducing population, pollution, greed, and selfishness.![]()

“That’s the cost to purchase or rent extra water allocation, not even counting that, just a drop in yield and the fact that if we get less water, the quality is not going to be there,” he said.

“It’s going to be a big deal for me and for many of the other farms in the area that have a similar crop mix.”

An eye to expansion

Alberta has the largest irrigated area in Canada, reaching about 690,000 hectares in the province. Of that, 566,000 hectares are in southern Alberta along the South Saskatchewan River Basin (SSRB). The Bow, Oldman and South Saskatchewan sub-basins located within the SSRB have all been closed to new surface water allocations since 2006.

The Red Deer River, Bow River and Oldman River basins, which are part of the SSRB, are part of what the provincial government has called “unprecedented” water-sharing negotiations. Results from those negotiations are due in mid-April.

Though water supplies in southern Alberta are under stress, the province is moving forward with a planned expansion of irrigation.

In 2021, Alberta’s government, the Canada Infrastructure Bank and Alberta’s nine irrigation districts announced they would invest a total of nearly $933 million over seven years in irrigation infrastructure. The move would create 7,300 permanent jobs and 1,400 construction jobs, and contribute up to $477 million to the province’s gross domestic product every year, according to a release.

Saskatchewan, which shares water with Alberta along the South Saskatchewan River Basin, is also set to start construction on a significant irrigation project.

Some of the proposed projects have been anticipated for what seems like forever. Take the Municipal District of Acadia, near the Saskatchewan border. In 2004, the M.D. commissioned a study with support from the provincial and federal governments to examine large-scale farmland irrigation in the municipality.

In 2021, the M.D. signed a memorandum of understanding with the provincial government, the Canadian Infrastructure Bank and the Special Areas Board to again examine the potential for such developments.

“I don’t really know how we get it lost in the weeds all the time. I guess the size of it has always been a bit of a hindrance,” said Scott Heeg, a councillor with the M.D. and a dryland wheat farmer.

For his family farm, such a large-scale irrigation project would mean a lot.

“In my mind, it would mean sustainability for our family farm and the surrounding community as a whole, for all our producers,” Heeg said.

“The population of the area out here is on a steady decline. We need something to sustain the area and keep the people here, and hopefully even grow.”

‘Where’s the water going to come from?’

Alberta’s planned irrigation expansion does raise questions for some.

“That announcement was made shortly after I moved to this province. And I literally did a bit of a head-scratcher, because, OK — where’s the water going to come from?” said Stadnyk, the Canada Research Chair in hydrologic modelling.

At the St. Mary River Irrigation District AGM, a common sentiment was that though Alberta is in a drought cycle, it will move into a wet cycle again. Stadnyk said such a sentiment is fair but doesn’t tell the whole story.

“As a hydrologist, I definitely agree that there’s always a cycle with the water,” Stadnyk said. “But what the science says is that this is one of the regions in the world where we can expect more frequent drought cycles, and longer drought cycles.

“That begs the question about economic viability, right? How long can farmers and irrigators hold out without that water and still be productive and still have a viable business?”

Back at the AGM, Westwood, the irrigation district’s general manager, understands the concerns. With a planned expansion of irrigation, in a drier and hotter future, solutions will need to be put on the table.

But Westwood said the district is confident that even though southern Alberta is on a path to irrigation expansion, it’s being done through infrastructure projects leading to strong water savings.![]() Pfffft. Bullshit, pure Alberta con Bullshit.

Pfffft. Bullshit, pure Alberta con Bullshit.![]()

“We are very confident that we can irrigate the same or more with less water than we have in the past,” Westwood said.

“By converting to underground pipelines, we save on seepage evaporation and spill-out at the end of our systems. That allows us to utilize that water for irrigation. That allows for the expansion.”![]() better to put solar panels over canals, than pipeline water.

better to put solar panels over canals, than pipeline water.![]()

Some of that is already playing out on local farms. Gary Tokariuk, president of the Alberta Sugar Beet Growers, farms about 1,000 acres — half rented, half owned.

“We’re actually using less water than we ever have. We have more acres, but we’re using less water. It’s an economic driver in our area, and you’re not going to have the McCain’s or any of these plants come here if there’s no water for irrigation,” Tokariuk said.

Alberta’s irrigation district managers, meanwhile, have proposed a $5-billion plan for water storage![]() ???

???![]() and conservation in the province’s south. The report brought together 40 organizations to reach its recommendations and focuses on the SSRB.

and conservation in the province’s south. The report brought together 40 organizations to reach its recommendations and focuses on the SSRB.

Margo Redelback of the Alberta Irrigation Districts Association told The Canadian Press that southern Alberta would continue to have enough water, with the exception of “extreme scenarios” in which glaciers no longer feed the basin.![]() Coming faster than most want to know.

Coming faster than most want to know.![]()

But it will probably come at different times of the year, Redelback said, or will drain away as runoff instead of being released slowly by melting ice or snow. Under all scenarios of warming, end-of-summer water flows are projected to be lower.

“It’s really about timing,” Redelback said. “We’re going to have more variable water falling.

“For that reason, there’s large potential storage projects that could be considered.”![]() Dams, including for frac water hoarding, have terrible negative impacts, and ought to never be considered. We are supposed to be smarter now after watching failed dam after failed dam.

Dams, including for frac water hoarding, have terrible negative impacts, and ought to never be considered. We are supposed to be smarter now after watching failed dam after failed dam.![]()

Water from irrigation is provided to more than 40 municipalities and thousands of rural residents in Alberta, while businesses also receive water through the system to support their operations, according to the provincial government.

No easy answers

Stadnyk, the Canada Research Chair in hydrologic modelling with the University of Calgary’s Schulich School of Engineering, says it’s virtually certain that Alberta will no longer have glacier inflow in the future — the only question is when this will occur, whether that’s in 2030 or 2050.![]() Or, 2026

Or, 2026![]()

And though storage is a potential solution to offset seasonality, there will also likely be an overall reduction in streamflow for prairie rivers, she said.

“There is general agreement from the climate models and hydrology on this. We will still have to learn to live with less, and be more efficient with our water use at all times of the year,” she said.

It’s also important to note that pipelines leak, Stadnyk noted, and efficiencies are never as high as textbook efficiencies one may expect to have in the system. Due diligence will be crucial in moving ahead, she said.

“The last thing we would want as a province as a whole is to spend millions of dollars, if not billions, retrofitting for irrigation expansion, only to find that the water isn’t there to fill the canals or the pipes,” she said.

Considering potential trends when it comes to temperature and water supply, Westwood said irrigators would need to start growing responsive crops that potentially could use less water.![]() And, install solar panels to shade and cool them, break the wind, prevent soil from drying out, result in much water need, and produce energy!

And, install solar panels to shade and cool them, break the wind, prevent soil from drying out, result in much water need, and produce energy!![]()

“I think irrigators are [thinking] about that. They’re looking at a lot of on-farm improvements, a lot of ways of looking at growing different varieties of crops that require less water,” he said.

There are a lot of unanswered questions here, and all involved agree it’s a complex and evolving process. Among those who believe more irrigation is possible in southern Alberta, technological efficiency is pointed to as the way forward.

For some, like Stadnyk, it’s clear that technology is advancing and things are becoming more water efficient. But it doesn’t solve every problem.

“I think we’re going to need every ounce of that efficiency just to overcome climate change, and these more frequent and longer droughts,” she said.

“It still begs the question, where is the extra water going to come from? I don’t have a good answer for that.”

This story is part of CBC Calgary’s ongoing series, When In Drought, which explores Alberta’s drought conditions — and how best to handle them. You can find the other stories here.

B.C. doesn’t know where all its groundwater is going. Experts worry as drought looms by Brenna Owen, The Canadian Press, April 10, 2024, Lethbridge Herald

Growing up on a ranch in the Columbia River Valley, water has always been part of Kat Hartwig’s life, and over the years, she’s noticed changes.

Marshy areas her family used for irrigation or watering cattle are dry, wetlands are becoming “crunchy” rather than spongy underfoot, and snowmelt is disappearing more quickly each spring, ushering in the dry summer months, Hartwig says.

Climate science supports her observations, showing that global heating is causing warmer temperatures and increasingly severe droughts in British Columbia.

Hartwig, who advocates for better water policy, and others say drought is exposing cracks in how the province manages water.

Officials don’t always know who is using groundwater it, how much they’re using, or where they’re drawing it from, experts say. There are gaps in mapping and other data that officials need to effectively manage water during times of scarcity.

The province doesn’t keep track of exact usage by most groundwater licence holders, the Ministry of Land, Water and Resource Stewardship confirmed. Rather, the licence sets the maximum amount of water each user can extract.

That’s the case for both domestic and some commercial users,including companies in the forestry, mining, and agricultural sectors, the ministry says.

At the same time, about two-thirds of pre-existing users have yet to even apply for licences since B.C. first began regulating groundwater in 2016.

The B.C. Energy Regulator publishes quarterly water-use reports for the oil and gas sector, and some other licensees may be required to report how much they use. Groundwater users may also be asked to complete a “beneficial use” declaration to show they’re meeting licence terms.

But it’s an incomplete picture of water use throughout the province at a time when signs point to deepening drought.

Hartwig, as well as Oliver Brandes, a lawyer and policy expert at the University of Victoria, and hydrogeologist Mike Wei, who retired from working for the province in 2018, say B.C. lacks sufficient mapping and details on groundwater sources.

B.C.’s minister for land, water and resource stewardship, Nathan Cullen, says drought wasn’t always front of mind for B.C. governments and the public.

“If there were worries (about) water, historically, there was often too much, right?”

Cullen’s fledgling ministry is now tasked with catching up to today’s climate reality and delivering the province’s watershed security strategy, expected sometime this year.

An intentions paper shows priority areas include enhancing monitoring and addressing data gaps.

The B.C.-First Nations Water Table is co-developing the strategy, and Cullen says the province is working to establish additional community-based groups this spring.

Many of those tables involve members of the agricultural sector, he says, pointing to the recent announcement of $80 million in additional funding for the province’s agricultural water infrastructure program to help farmers weather times of drought.

“The scope and scale of the challenges is real to my mind,” Cullen says.

But “standing up what may be dozens and dozens of these community water tables in short order … is very much in the government’s interest,” he says.

“This costs us one way or the other,” the minister adds. “Better water management is a lot cheaper than the management of crisis, similar to forest fire mitigation.”

As executive director of Living Lakes Canada, Hartwig works to build capacity for community-based water monitoring and fill the gaps in provincial data.

“We’re also helping to educate and build a water-literate constituency, so people understand that groundwater is a treasure and not to be wasted,” she says.

There were just two groundwater observation wells in the Columbia Basin when Living Lakes began monitoring in 2017, she says. Today, there are more than 30. Last year they registered some of the lowest water levels, Hartwig adds.

In 2021, Living Lakes launched an open-access hub to bring water-related data from the Columbia region together in one place from sources including local governments, First Nations, community groups and the private sector.

But the experts say it’s just scratching the surface of what’s needed.

‘HALF A CENTURY OF NEGLECT’

B.C. has regulated surface water for more than a century, but before the Water Sustainability Act came into force in 2016, that wasn’t the case for groundwater, says Wei, who helped the province develop the legislation.

Before 2016, he says, landowners could drill next to a stream and pump groundwater, potentially depleting surface water, without provincial knowledge.

That’s changing, but Wei says B.C. is “dealing with half a century of neglect.”

He says B.C. has mapped 1,200 aquifers with about 240 observation wells, most on the South Coast and in the southern Interior.

But much of the mapping is “rudimentary” and monitoring infrastructure inadequate, Wei says. It often doesn’t tell officials how much water is being used, which direction it’s flowing, and what the sustainable supply from an aquifer might be.

Cullen says he “always (wants) more data,” and the province is expanding monitoring sites.

“I think increasingly, there’s an understanding from water users and the general public that we’re into an era where we’re going to have to be a lot more precise and inclusive when we make decisions around water, especially groundwater use.”

B.C. has been working to bring people who use groundwater into the licensing system introduced with the 2016 legislation. The province offered existing users a six-year transition period to obtain a licence with the date recognizing their first use of the groundwater.

The date is crucial because licences showing newer usage are the first to be cut off during water scarcity under the “first in time, first in right” system, says Brandes,who leads the POLIS Water Sustainability Project at the University of Victoria.

Yet the province received just 7,700 applications from some 20,000 existing non-domestic users by the time the transition ended.

Those who didn’t register may face a “rude awakening,” Brandes says.

“In a few places, there is basically not enough water,” ![]() There are too many humans wasting sufficient water supplies and causing water permanent harm (Site C dam a perfect example). Water is not the problem, humans are. As long as humans chase water and work to change it to fit exponential growth of human greed and population, there will be severe water shortages.

There are too many humans wasting sufficient water supplies and causing water permanent harm (Site C dam a perfect example). Water is not the problem, humans are. As long as humans chase water and work to change it to fit exponential growth of human greed and population, there will be severe water shortages.![]() he says. “The people who … weren’t signed up in the transition period are going to be in a tough spot.”

he says. “The people who … weren’t signed up in the transition period are going to be in a tough spot.”

They can still apply for a licence moving forward, but it would no longer reflect when they first began using groundwater, Brandes says.

Cullen says sign-ups came in “dramatically” below what officials had hoped for and what the province needs to manage water.

“It’s difficult to manage if you’re not properly measuring,” the minister says.

“We’re trying to broadly understand the resistance to people getting licensed and to lower (it),” he says, adding things are “trending in the right direction.”

“We’re understanding the full actual nature of it in a much better way than we did, say, five years ago,” he says.

But Brandes says the slow progress and general lack of “vital signs” about water in B.C. led to a “disaster” last summer, when critically low flows in several waterways prompted the province to issue fish protection orders that restricted the irrigation of forage crops in parts of the southern Interior.

The orders cut off several hundred surface and groundwater users and some ranchers resorted to selling livestock as they grappled with the shortage of feed.

Brandes says the province’s handling of the situation contributed to uncertainty, social conflict, and a loss of public trust.

Wei, too, says the orders lacked transparency. “People didn’t know why they were being shut off. Science wasn’t necessarily getting out there.”

He says a lack of proactive investment in understanding water and building capacity to respond to drought leads to “scrambling” in the face of urgent situations, and scrambling is costly, financially and democratically.

“When you don’t have information, it’s not transparent, you erode public confidence in what you, the administrator for the resource, can do.” he says.

“And when you start eroding it, you’re eroding your democratic foundation.”

The conversation in the Interior last summer “went badly,” Cullen says, adding that restrictions are “the last thing” the government wants.

“Coming together is the path forward, and that’s what we’re doing. That’s why we’re having those conversations in 20-plus communities already.”

Hartwig says the work in the Columbia Basin serves as a template and underscores the importance of community-led water monitoring and governance.

The project has uncovered streams that were “over-allocated” with licences, she says, as well as dry areas where government maps indicated high-elevation wetlands.

Yet she says three dozen community-based groups in the Columbia region have been forced to stop their work due to funding cuts in recent years.

“We have a huge amount of attrition of these small, volunteer-based water monitoring groups who are very concerned about their own watersheds,” she says.

“We need those boots on the ground. We need that level of water literacy, and we need them to participate in civil society, right? We can’t have that eroded.

“And that’s not being fortified by the province.”

***

Drought, heat raise risk of repeat of last summer’s record-breaking wildfires by The Canadian Press, April 10, 2024, The Lethbridge Herald

Persistent drought and months of above-average temperatures have raised the risk of a repeat of last year’s record-breaking wildfires.

Federal officials say conditions are already ripe for an early and above-normal fire risk from Quebec all the way to British Columbia in both April and May.

But Michael Norton, the director general of of the Northern Forestry Centre at Natural Resources Canada, says in the spring the main risk factor is humans.

While lightning becomes the main source of wildfires in the summer, most spring wildfires are started accidentally by people.

The 2023 fire season was Canada’s worst ![]() year for wildfires (calling the horrors currently caused by wildfires because of human fossil fuel pollution, greed and over population, a “season” normalizes it, like spring or fall “season.” There is no wildfire “season.” There are wildfires, growing more extreme the more we foul humans pollute and intentionally destroy water.

year for wildfires (calling the horrors currently caused by wildfires because of human fossil fuel pollution, greed and over population, a “season” normalizes it, like spring or fall “season.” There is no wildfire “season.” There are wildfires, growing more extreme the more we foul humans pollute and intentionally destroy water.![]() on record, burning more than 15 million hectares and forcing more than 230,000 people from their homes.

on record, burning more than 15 million hectares and forcing more than 230,000 people from their homes.

In response to a request from Canada’s fire chiefs, Ottawa says it will double the tax credit for volunteer firefighters from $3,000 to $6,000.![]() Insufficient pay, considering fighting wildfires is a deadly job, and extremely hard and toxic.

Insufficient pay, considering fighting wildfires is a deadly job, and extremely hard and toxic.![]()

‘A societal issue’: Drought-plagued Alberta braces for even worse conditions, Province will push ‘water sharing.’ Cities will restrict usage. This year could get drastic by Jason Markusoff, CBC News, Feb 01, 2024

Day after day, the water trucks rolled into the southwest Alberta communities of Cowley, Lundbreck and Beaver Mines. Due to severe drought conditions, that’s how residents and businesses got their water supply between last August and late December.

Those communities normally get water piped in from the nearby Oldman Reservoir. But its water levels became so low that the intake pipes were suddenly sucking in prairie air instead — requiring the desperate (and costly) truck solution.

Engineers have figured out a pumping solution to stop the need for daily trucks, but sometimes they still have to haul when the pipes pick up too much silt and sediment from the parched reservoir’s bed, says David Cox, reeve of the Municipal District of Pincher Creek.

Water issues have become most of what he talks about — with residents facing sharp usage restrictions, with fellow municipal leaders and farm groups, with provincial officials on a now-regular basis.

“Nobody started talking about this issue until we ran out of water and started hauling it,” the reeve tells CBC News. “It’s not just our issue. It’s a big issue for everybody.”

As bad as last year’s drought situation was — water trucks to Cowley, feed crunches for cattle farmers, lawn-sprinklering limits in Calgary — many indications show that this year threatens to be even worse in much of Alberta and the rest of western Canada.

Dry January, February, March…

The Alberta government’s creeping sense of urgency showed up Wednesday. Environment Minister Rebecca Schulz sent a letter to all 25,000 holders of water licenses in Alberta, launching negotiations to get users to reach water sharing agreements.

A provincial “Drought Command Team” — name carries some gravitas, doesn’t it? — will work with major water users in sectors like agriculture and industry to “secure significant and timely reductions,” the minister’s letter states.

A day earlier, Schulz and other top officials held a telephone town hall with a wide range of Albertans from water commissions, local councils, oil companies and the golf course association.

Stacey Smythe, an assistant deputy minister with Alberta Environment, put forth many grim stats.

The Oldman Reservoir west of Fort Macleod is at 28 per cent capacity, compared to a normal range between 62 and 80 per cent around now. St. Mary’s Reservoir is at 15 per cent, when it should be between 41 and 70.

Before freeze-up, Willow Creek near Claresholm logged its lowest monthly flow since 2000. And while northern Alberta watersheds mostly aren’t as bad, up at the town of Peace River the namesake river has also logged its lowest average flow this century.

Those water bodies mostly get recharged from melting mountain snowpack, and the accumulation in this mild, dry winter is lower than last year’s.

“More than agriculture will be impacted if this extreme level of dryness continues,” Smythe said. “The situation is going to impact all of Alberta. It is a societal issue — not an environmental issue.”![]() Bullshit. Big fat frac lie. It is environment, it’s human over population, over pollution, gross greed and waste of energy, water, housing, travel, etc.

Bullshit. Big fat frac lie. It is environment, it’s human over population, over pollution, gross greed and waste of energy, water, housing, travel, etc.![]()

The drought threatens to reach so many parts of society and the economy.

Shortages could force more ranchers to downsize their cattle herds. Some oil and gas companies have begun facing crackdowns on their water use, and more may come as sharing negotiations pick up.

Municipal Affairs Minister Ric McIver was on that town hall call, predicting that trucked-in water will likely be necessary again into 2024. Ditto for urban water restrictions.

In Edmonton, a water treatment pump issue prompted a citywide alert this week to limit business and household water use, including a plea for short showers instead of baths. That could be a dress rehearsal for what much of Alberta, especially in southern communities, could be asked to comply with later this year.

“I have a lawn and a sprinkler and I’m prepared not to turn on that sprinkler all summer, if that’s what’s required ![]() gonna take one hell of a lot more sacrifice than that miserly reduction

gonna take one hell of a lot more sacrifice than that miserly reduction![]() to feed the livestock and the crops and for other people,” McIver told the town hall.

to feed the livestock and the crops and for other people,” McIver told the town hall.

The worst could be prevented by some heavy snow later this winter or the sort of springtime downpour that some rural folk call “trillion-dollar rain.”

But an El Niño system such as this year’s, coupled with the chronic heating effects of climate change, do not bode well, says John Pomeroy, the Canada Research Chair in water resources and climate change.

Groundwater by Kananaskis’ Marmot Creek is at its lowest levels in more than a half-century, he said; and tracking of the Bow River at Calgary last summer showed it lower than ever measured, back to 1911.

The recent chinooks were warm enough to melt snow above the mountain treeline.

“Seeing an alpine melt in January is unprecedented in my experience,” Pomeroy says.

It’s encouraging, the veteran water scientist says, that provincial officials are talking about it seriously early in the year, rather than getting caught off-guard later when (or if) disaster strikes.

Top government officials have thus far avoided drawing links between worsening drought and climate change, given how Premier Danielle Smith and many on her team are uneasy talking ![]() refuse to talk

refuse to talk![]() about climate change and its consequences.

about climate change and its consequences.![]() or they out right lie about it, deny it, corruptly and idiotically serving petroleum polluters and ravagers of water.

or they out right lie about it, deny it, corruptly and idiotically serving petroleum polluters and ravagers of water.![]()

But this could be the sort of crisis year when symptoms become so acute that discussion of causes may appear more secondary.

‘All in this together,’ redux

Smythe, the senior civil servant, echoed some of Schulz’s own rhetoric in saying that, on water, “we’re all in this together. This situation has never been more true than it is today.”

The line echoes something else, too — the message from now-former chief medical officer Dr. Deena Hinshaw in the early stretches of the COVID pandemic. It caused citizens and businesses alike to restrain and compromise their own activities and freedoms for the betterment of the whole.

Those exhortations and orders to reduce and restrict for everyone’s wellbeing will make a comeback if the severe drought scenarios materialize. Schulz and Smith will face pressure to declare a new provincial state of emergency.

During her largely dire presentation on the state of dry Alberta, Smythe also made an optimistic point about the public’s willingness to comply. While Calgary imposed water restrictions, Red Deer didn’t, she noted — but because its residents consume Calgary media, the messages put a dent in that central Alberta city’s water use, too.

Dried-up rivers and parched fields may demand Albertans to all be in this together in 2024, to share, to compromise. That collective spirit didn’t always work so well throughout the pandemic, and our current premier was among those who pushed back — but this time is necessarily different.

Smith leads a government that must steward a public resource we all use, and the consequences could be dire and wide-ranging if the collective fails to do so.

![]()

Refer also to: