The anatomy of a protest: Moncton sociologist digs into Rexton shale gas protests, Moncton woman probes anti-shale gas activities in Kent County for sociology thesis in Ottawa by Jennifer Sweet, CBC News, Jan 18, 2020

55 comments

It’s not often New Brunswickers unite around an issue across linguistic and cultural lines.

A sociologist from the University of Ottawa says that’s why she was so intrigued by anti-shale gas demonstrations in the province between 2010 and 2016.

At the time, exploration was taking place and being planned in a few parts of the province.

At the height of protests in Kent County, dozens of people were arrested and [stripped (clearly obvious in photo below)] RCMP vehicles were set on fire by Police (ordered by Steve Harper?), to discredit Canadian citizens opposed to be poisoned by frac’ing??] after police moved to enforce an injunction against a blockade by people protesting against shale gas exploration work.

Marie-Hélène Eddie, who is originally from Moncton, was studying in Ottawa in October 2013. She followed events in the news when Indigenous protesters and RCMP clashed violently in Rexton.

She decided to study the protest movement for her doctoral thesis at the University of Ottawa, which was published last month.

The thesis focuses on three groups — Mi’kmaq, Acadians and anglophones — and how they mobilized against development of the shale gas industry.

Protests all over the province

Eddie had the impression the protest movement was being led by First Nations people in Kent County.

One of the first discoveries she made in her research was that this was not the case.

“It was happening all over the province, not just in Kent County. It was happening in Fredericton mainly and in other regions as well.”

In Kent County, however, Eddie discovered that the first group to organize was Acadian — Notre Environnement, Notre Choix — based in Saint-Louis. In English, the group is called, Our Environment, Our Choice.

They were followed closely, said Eddie, by an anglophone group called Upriver Environmental Watch, near Rexton.

Indigenous people actually joined the fight “months, if not years later,” she said.

Media coverage having a role

Eddie speculated this staggered entry may have been related to media coverage.

“Different groups can have different access to the media,” she said.

French-language journalists in the province tend to be “very eager” to support the Acadian community, while Indigenous people “essentially have no media supporting them.”

She documented some differences in coverage among news outlets.

Eddie analyzed 296 articles from various news outlets.

She found articles in Irving-owned publications gave precedence to voices in favour of shale gas development 53 per cent of the time. The rate was 24 per cent for articles in non-Irving-owned publications.

Brunswick News reports cited industry sources first 30 per cent of the time. The rate in articles by other publishers was eight per cent.

“Irving media had coverage that was more biased towards the industry and towards shale gas development,” she said.

“It’s important to research that, to see that, to discuss that and to ensure that in New Brunswick we have a variety of media with a variety of ownerships — which we don’t presently have.”

Eddie was quick to add that some of the differences in coverage were “subtle” and she didn’t think there was any “malice” involved.

“The journalists themselves I really think tried to do their job as well as they could,” she said. “That was very apparent in the interviews.”

The journalistic resources on the ground in different parts of the province probably also had an impact, said Eddie.

For example, the French media more frequently have a journalist that is assigned to Kent County than the English media

“When you’re covering, for example, the Rexton protest from Fredericton, it can become difficult to get people to give you interviews over the phone. … It can be difficult to get the resources to travel to Kent County regularly. So it affects your capacity as a journalist to create relationships with the people on the ground and get the scoop and know what’s going on.”

Finding common ground

Eddie was initially planning to focus on the way linguistic minorities mobilize or organize beyond linguistic issues. But she had to rethink her theoretical framework to account for the broader participation.

“I kept thinking, well, are anglophones really a minority? They clearly are not a minority the same way that First Nations are. They don’t have the same barriers, the same issues.”

As she dug deeper, it became obvious that many of the people involved in the movement actually had a lot in common. [Ya, we don’t want to be poisoned by frac’ing! We know our regulators and courts will never serve frac-harmed Canadians justice or remedy.]

For one thing, supporters of the movement predominantly lived in rural areas, where exploration and potential shale gas development would take place.

And in Kent County, where she focused her research, anglophone residents had very similar socio-economic status to Acadians and Indigenous people. They were relatively poor and had relatively low levels of formal education.

“It really seemed that all three groups actually were very disadvantaged compared to the rest of New Brunswick or the rest of Canada.”

LISTEN AT LINK: Information Morning – MonctonA PhD student looked at the opposition to shale gas development in New Brunswick and how the news media covered it. Marie-Helene Eddie made the shale gas protests the subject of her doctoral thesis at the University of Ottawa. 14:30 Min.

She was blown away at how protest leaders were able to overcome these apparent barriers to get people involved.

“I still kind of get shivers thinking about it sometimes. … They were very aware of their audience — being people who can sometimes be intimidated by the government, or people who may think that it’s impossible that they’ll succeed in the fight or people, in some cases, who didn’t know how to read very well.”

Community meetings and information sessions were held where different aspects of the issue were explained, like the meaning of a moratorium, for example, the amount of water needed for shale gas exploration and exploitation, the known risks and the findings of the latest studies.

“Just informing people — not telling them what to think, but getting them the facts that they needed to decide by themself what they thought about shale gas.”

At the provincial level, Eddie said, the protest movement built momentum and unity through the formation of an umbrella group— The New Brunswick Anti-Shale Gas Alliance — and the designation of single anglophone and francophone spokespersons — Jim Emberger and Denise Melanson.

Support never approached unanimity, said Eddie, but the movement still proved effective.

“It was a dividing issue and it’s hard to tell how much the groups had an impact on public opinion.”

With files from Information Morning Moncton

Refer also to:

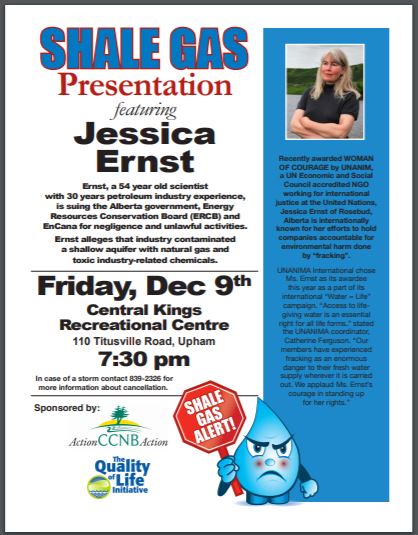

2011: Scientist in N.B. to tell hydro-fracking story

One of the country’s biggest critics to hydraulic fracking is in New Brunswick for two days to speak to people concerned about shale gas exploration.

Jessica Ernst, a scientist, said she believes hydro-fracking in her Alberta community polluted her well with methane gas and other chemicals.

“I began getting a terrible rash, I had irritated eyes after bathing,” she said.

Ernst is suing the province, its energy conservation board and EnCana for $33 million. She said all the parties were negligent and she wants New Brunswickers to know about the risks.

“Even with a methane detector in my home, if the detector went off, most likely I would blow up before I got to the door because it just takes a light switch or a spark to ignite,” she told CBC News.

“I don’t want to live with that.”

Provincial Environment Minister Margaret-Ann Blaney said she vows to learn from the mistakes of other provinces before hydro-fracking happens in New Brunswick.

She said she will implement the toughest regulations in the country.

“If we can’t do it responsibly and safely and absolutely protect our drinking water and the environment, ensuring the safety of all of that, then we’re not going to do it,” Blaney said.

Ernst is skeptical.

“If they cannot get EnCana to heed the regulations and the laws in place to protect ground water in Alberta, you’re not going to have a chance of getting the companies to do that here,” Ernst said.

That’s what Stephanie Merrill with the Conservation Council of New Brunswick worries about.

“It’s one thing to do your homework and put in place regulations to help minimize your impacts,” Merrill said.

“But this industry has inherent risk and impacts that you can’t regulate away.”

Merrill said the province needs to be upfront about the potential impacts of hydro-fracking on water, air quality and on their health.

“It doesn’t matter how far down the seismic program or even how far down the exploratory drilling or the hydraulic fracturing has taken place,” Ernst said.

“We can put a stop to this.”

Ernst will be speaking in Upham on Friday and Memramcook on Saturday.

2011 12 10 Jessica Ernst at Memramcook with Florian Levesque New Brunswick

2011 12 09 Jessica Ernst Presentation at Upham New Brunswick