Is a client’s right to freedom of thought and expression (eg posting articles, comments about a legal system inaccessible for nearly all civil Canadians, bad behaviour by judges and lawyers, etc) a valid reason for lawyers to quit a lawsuit? White supremacy certainly isn’t.

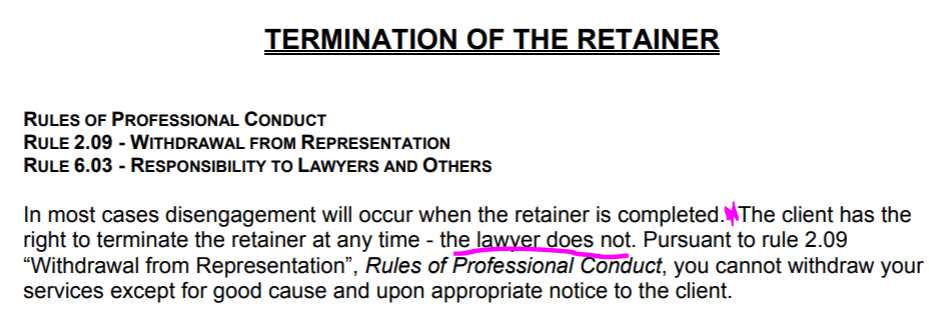

Law Society Ontario Rule 2.09, withdrawal from representation:

Les avocats de Jessica Ernst l`abandonnent French translation of Andrew Nikiforuk’s article ongoing, time permitting, by Amis du Richelieu

Another Setback in Landmark Fracking Case as Lawyers Pull Out, Jessica Ernst’s 12-year legal battle over water contamination no nearer resolution by Andrew Nikiforuk, August 8, 2019, The Tyee.ca

Andrew Nikiforuk’s book on the Ernst case, Slick Water, won a Science in Society Journalism Award from the U.S. National Association of Science Writers in 2016.

Jessica Ernst has spent 12 years and $400,000 pursuing a lawsuit against the Alberta fracking industry and its regulator.

Now her Ontario lawyer has let go most of his staff and given up the case.

“I was shocked and felt terribly betrayed,” said Ernst. “The legal system doesn’t want ordinary people in it. They don’t want citizens who will not gag and settle out of court for money so corporations and government can continue their abuse.”

In 2007, Ernst, then an oil patch consultant with her own thriving business, sued the Alberta government, Alberta’s energy regulator and Encana. She alleged her well water had been contaminated by Encana’s fracking and government agencies had failed to investigate the problems.

For more than a decade the case has been bogged down by legal wrangling, legal posturing and constant delays. Three different judges have been involved.The Tyee is supported by readers like you Join us and grow independent media in Canada

The process included a two-year detour to the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled that Ernst could not sue the regulator because it is given immunity by provincial legislation. The lawsuits against the provincial government and Encana remain before the courts.

And still no evidence has been heard on the actual merits of the case.

Ernst was represented by high-profile lawyer Murray Klippenstein. He told The Tyee in an email that “major changes in the political climate of the legal profession in Ontario” made it “no longer feasible for me to continue my law firm. That was heartbreaking to me, for many reasons.”

Klippenstein is fighting against a recently adopted Law Society of Ontario statement of principles that obliges law firms to “promote equality, diversity and inclusion” and perform annual “inclusion self-assessments.”

Lawyers “will increasingly be judged more on the basis of ideology, skin colour and sex chromosomes than by their competence, skills, effort and professional contributions” under the rule, he argued.

However, advocates for the new rules say criticism from Klippenstein and others showed how badly they are needed.

Legal scholar Joshua Sealy-Harrington argued that the “forceful opposition” showed the insufficient awareness of systemic discrimination in Canadian legal practice, which has been detailed time and time and time and timeagain.

Klippenstein also offered another reason for quitting the case, saying in an email to The Tyee that he “had increasing concerns about Ms. Ernst’s views about the viability of her own lawsuit, in particular because of Ms. Ernst’s highly and increasingly critical views of the legal system, and of the lawyers that were a part of that system, to the point where I thought it was simply no longer viable for us to represent her going forward.”

Ernst said she fully explained her critical views to Klippenstein in 2007 as she vetted potential lawyers. Those views have never changed, she added.

“Murray warned me in 2007 that I would need to spend a million dollars and give up 10 to 12 years of my life, to maybe win a few thousand dollars,” said Ernst.

She said Klippenstein told her that lawsuits like hers were usually settled with a payment and a non-disclosure agreement that silences the person who had sued “because our legal system is set up to make that happen.”

Ernst said she had always been clear that she would not accept a non-disclosure agreement. The issue of contaminated water goes beyond one household or community and the public needs to be aware, she said.

Ernst said Klippenstein also warned her that the courts might order her to pay the legal costs of Encana and the other defendants even if she won the lawsuit.

“I would have to also pay the legal costs of the defendants even if I win but win less than what the defendants offer me to gag,” she said. “Who wouldn’t be bitter?”

Ernst’s lawsuit claims fracking contaminated the water supply at her homestead near Rosebud, about 110 kilometres east of Calgary. Research has shown fracking, in which companies blast water, chemicals and sand underground to crack rock formations and allow methane to flow, can result in groundwater contamination.

The suit alleges that Encana was negligent in the fracking of shallow coal seams; that the regulator breached Ernst’s freedoms under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and that Alberta Environment performed a problem-plagued investigation in bad faith.

Even before the lawsuit was launched, Ernst was locked in conflict with the Energy Resources Conservation Board, now the Alberta Energy Regulator. In November 2005, the regulator sent Ernst a letter saying it had told its staff to “avoid any further contact” with her on the grounds that she had criticized the board and made “criminal threats.”

But in June 2006 Rick McKee, then chief counsel for the regulator, admitted in a taped interview (Liberal MLA David Swann was a witness) that Ernst never presented a security threat to the organization.

She also sued the regulator for violating her charter rights by falsely branding her a “criminal threat” in 2005.

The Supreme Court of Canada split ruling on Ernst’s right to sue the energy regulator included a claim by Justice Rosalie Abella that the regulator found Ernst to be a “vexatious litigant,” though no regulator in Alberta has ever described Ernst as such. Four of the other justices commented on Abella’s claim, noting, “We see no basis for our colleague’s characterization.”

But Ernst has been unsuccessful in having the statement corrected in the judgment, noting it could be used against her in future hearings. The Canadian Judicial Council informed Ernst that it has no policy for correcting errors and that only the Supreme Court can amend or review reasons for its decisions.

Some legal scholars criticized the Supreme Court decision and said it weakened the Charter of Rights and Freedoms by allowing governments to place regulators above the law.

Ernst learned Klippenstein was withdrawing from the case last fall, but didn’t share the information until recently. She was waiting until the law firm surrendered control of her website, she said. The website is an archive of her lawsuit as well as a record of the political, legal and ecological impacts of the brute force technology of fracking.

The Tyee asked Klippenstein why the case has floundered in the justice system for nearly a dozen years.

“Ms. Ernst’s case was and is an enormously ambitious undertaking, involving numerous highly-complex scientific and legal issues, against a number of very powerful, very well-resourced, and very determined opponents,” he said. “We all knew that from the beginning, and we all knew that it would be an incredibly difficult and lengthy and time-consuming effort to undertake it, and a seriously uphill battle all the way.”

Klippenstein said he advised Ernst that she now has three options: she can transfer the case to another lawyer; continue with the lawsuit by representing herself; or let Klippenstein wind down the lawsuit “in a way that is most advantageous or least disadvantageous to you.”

Ernst said that she has rejected the third option.

“I have always been public and open about my case. But since I have no lawyers, I can’t disclose to The Tyee as much as I would like about my next steps,” she said. “I need to keep those options to myself.”

Ernst is philosophical about the latest setback.

“I am a lot less bitter now than I was when I started my lawsuit in 2007,” she said. “I have a wild sense of humour. What I have learned is that Canada’s legal system is a farce.”

“We don’t have a justice system, but a legal system designed to serve the interests of the powerful and to employ judges and lawyers.”

An Ernst chronology

Jessica’s Ernst’s lawsuit against Alberta’s fracking industry and its regulators provides a blunt view of how slow and protracted Canada’s legal system has become.

May 1, 1998: Ernst moves to a small rural property in Rosebud, Alberta. Her well produces soft, high-quality water. Water tests state “Gas Present: No.”

2001: Encana begins an experimental shallow fracturing natural gas project around Rosebud, without consulting with the community or landowners in violation of the Alberta energy regulator’s requirements.

Feb. 14, 2004: Encana drilled and later hydraulically fractured in the drinking water aquifers supplying Ernst, a dozen families and the Hamlet of Rosebud.

January 2005: An explosion at the Rosebud water tower seriously injured a Wheatland County worker. It was reported that an investigation determined the explosion was apparently caused by “an accumulation of gases.”

Nov. 24, 2005: The energy regulator (then the Energy Resources Conservation Board, now the Alberta Energy Regulator) sends a letter to Ernst. It brands her criticisms of the regulator as a “criminal threat” and says it ceases all communication with her.

Dec. 6, 2005: Ernst sends a letter seeking clarification on the regulator’s decision to cut off communication. It is returned unopened.

June 8, 2006: Regulator lawyer Rick McKee questions Ernst in a recorded conversation with a witness. McKee admits that the regulator never saw her as “a criminal threat,” but as an unwelcome critic. He also asks Ernst what it will take to get her to leave Alberta. Ernst replies she will gladly leave Alberta as soon as the regulator starts to do its job.

December 2007: Ernst hires lawyer Murray Klippenstein and files a $33-million lawsuit against Encana, the Alberta environment ministry and the Energy Resources Conservation Board alleging groundwater contamination was caused by the shallow fracking of coalbed methane wells in central Alberta.

Feb. 12, 2009: RCMP officers arrive at Ernst’s home without warrants to ask questions.

Oct. 24, 2009: Prime minister Stephen Harper announces the appointment of Neil Wittmann as new Alberta chief justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench.

July 19, 2010: The U.S. Congress investigates fracking practices, including the impact on drinking water. Encana is one of the companies questioned.

June 24, 2011: The Harper government appoints Barbara Veldhuis to the Court of Queen’s Bench.

Oct. 1, 2011: UNANIMA International, a U.S. NGO, presents Ernst with a Woman of Courage award in New York City.

April 26, 2012: The first hearing on the lawsuit takes place in the Court of Queen’s Bench in Drumheller. Justice Veldhuis requests a shorter statement of claim and volunteers as case manager. Energy regulator lawyer Glenn Solomon asks that the original statement of claim be removed from the court and public record. The request is denied.

Oct. 1, 2012: Defendants apply to have the case moved to Calgary during a case management call with Justice Veldhuis. Justice Wittmann later accepts the application to move the case to Calgary.

December 2012: In its legal brief filed with the court, the energy regulator changes its 2005 accusation that Ernst posed a “criminal threat” and described her as being an “eco-terrorist.”

Jan. 18, 2013: A second court hearing takes place in Calgary, where the courtroom is packed. Ernst refused to accept the change of venue and attends the Drumheller Court House with a witness. Encana does not argue to have the case struck, though the company website states that the case has no merit.

Feb. 8, 2013: The Harper government promotes Justice Veldhuis to the Alberta Court of Appeal. She advises that ruling on arguments in the Ernst case is “not an option.”

Feb. 15, 2013: During a case management call, Justice Veldhuis says Justice Wittmann has volunteered to take over the case.

Sept. 19, 2013: Justice Wittmann, despite not having presided over the original hearing, rules Ernst has a valid Charter of Rights and Freedoms claim but that the regulator is protected by legislation giving it immunity from civil litigation. He dismisses the regulator’s claim that Ernst is an “eco-terrorist” due to “the total absence of evidence.” He denies the Alberta government’s attempts to get the word “contamination” removed from Ernst’s statement of claim.

January 13, 2014: During a case management call, Justice Wittmann grants the Alberta government another chance to try to get Ernst’s case thrown out (at great cost of time and money to her). The hearing is set for April 16, 2014, and the case is moved back to Drumheller, where by law, it belongs.

Feb. 18, 2014: The Alberta government files a brief to strike the lawsuit against it. It argues the government has no duty of care to landowners and immunity. The motion comes three years after the lawsuit was launched.

March 18, 2014: Ernst responds to the government. Her lawyers argue that the approach taken by Alberta Environment is an abuse of process.

April 16, 2014: Drumheller Court of Queen’s Bench hears the Alberta government’s application to be removed from the Ernst case. Justice Wittmann orders document exchange between Ernst and Encana.

Sept. 15, 2014: The Alberta Court of Appeal rules that Alberta’s energy regulator cannot be sued by citizens even if it breaches constitutional rights.

Nov. 10, 2014: Chief Justice Wittmann rules that Alberta Environment can be sued. He orders Alberta Environment to pay Ernst “triple costs,” still less than the legal cost of protecting her case from having been thrown out.

Nov. 13, 2014: Ernst’s lawyers appeal the ruling on the regulator’s immunity to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Jan. 30, 2015: The Alberta government finally files its statement of defence.

Nov. 4, 2015: The Hamlet of Rosebud sends a petition to the Supreme Court of Canada arguing the energy regulator should not be exempt from lawsuits over Charter violations. It is rejected and not included in the docket. On a different case a letter from the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers is accepted.

Jan. 12, 2016: Supreme Court of Canada hears the case.

Jan. 13, 2017: In a split decision the Supreme Court of Canada rules that Ernst cannot sue the regulator.

Jan. 17, 2017: Chief Justice Neil Wittmann announces his retirement and recommends that the parties choose a replacement case management judge together. Ernst instructs her lawyers to write, “Our client believes that case management is not in her interest and therefore requests that the matter no longer be subject to case management… Our client also does not believe that it is appropriate for the parties to play a role in selecting a case management judge.”

Jan. 27, 2017: Encana and Alberta Environment provide their preferred judges to replace Justice Wittmann. Justice Eamon, one of their preferred judges, becomes the new case management judge.

March 29, 2017: The court orders case management to continue.

Aug. 26, 2018: Klippenstein and Wanless resign from the case.

June 30, 2019: Ernst announces that her lawyers have dropped her landmark case. To date, Encana still has not disclosed key records to Ernst, as required by Alberta’s Rules of Court and ordered by Justice Wittmann in July 2014

Email sent to Ernst from Republic of Ireland responding to above article:

Hi Jessica

Good to see your still strong.

The establishment don’t know what to do with you. It’s clear from the comments that your story is well known now. Your credibility with the public is growing every year. It’s clear your operating in the public interest. I hope new lawyers step up.

Regards

Ed

Comments in The Tyee to Nikiforuk’s article: