A tiny sampling of men in positions of power since I began speaking out about frac harms:

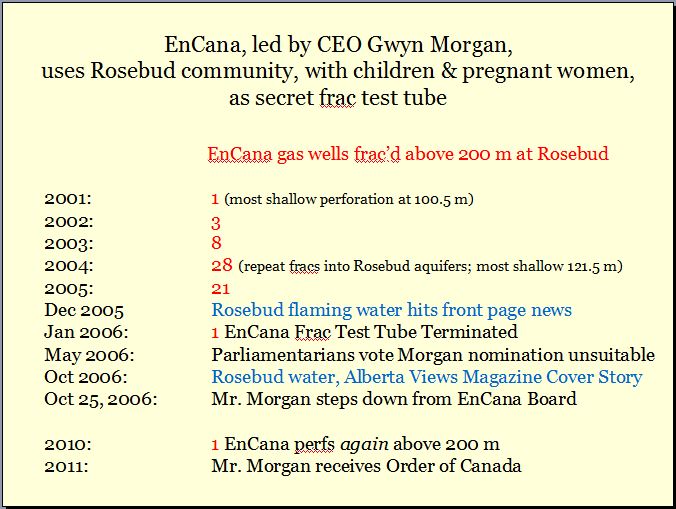

Gwyn Morgan was CEO of Encana (now Ovintiv) and led the company to rape Rosebud’s fresh water aquifers that supply my community and me with drinking water. His abuses to us were well rewarded:

Jim Reid, manager at AER (then EUB) when the regulator violated (in writing) my charter rights, trying to terrify me silent and make me stop asking for regulation of Encana’s crimes, judging me (without any evidence, trial, hearing or due process) a criminal, copying Alberta’s Attorney General and the RCMP (who later trespassed on my private property, two men against one frac’d woman, trying to terrify me into dropping my lawsuit against AER, Encana and the Alberta gov’t, and into submissive silence).

David DeGagne, manager at AER, bullied and tried to intimidate me while refusing to regulate law-violating Encana, and enabled the company’s fraudulent noise studies at Rosebud.

Neil McCrank, lawyer and head of the AER when the regulator let Encana and Gwyn Morgan frac (rape) Rosebud’s aquifers and refused my registered mail, treated me – a frac-harmed Canadian scientist seeking regulation from the regulator – like garbage.

Rick McKee, lawyer at AER, under instructions from Neil McCrank, continued to bully and tried to control me, a solitary frac’d woman, to protect Encana and AER’s status quo (law violations and rape and pillage of Alberta’s drinking water and communities for corporate and Gwyn Morgan’s profit).

Peter Watson, Deputy Minister Environment at the time (now head of the national energy regulator), angrily ordering me not to talk about his ministry covering-up Encana’s crimes! Read all about it in Andrew Nikiforuk’s Slick Water.

Tom McGee, a slimy (in many more ways than one) PR person at AER inappropriately touching me without my consent, slithering his body up mine in a public meeting in Cochrane, Alberta, on frac’ing, where a landowner (a male lawyer), publicly stated – in tears – he was unable to get baseline testing for his water well before frac’ing.

Angry Alberta men, cowardly in groups, dropping in at my private residence threatening me (and stressing my dogs) to shut up (speaking out and to media is only allowed by men they said but they were all too chicken to say peep), after Encana violated Alberta privacy laws, handing out a map in a public meeting, showing the location of my residence, and my name.

Murray Klippenstein and Cory Wanless, previously my lawyers, men I put my faith and trust in to serve my frac’d water and the public interest, violating the rules of their profession, abruptly quitting my case (and blaming me), while not quitting other cases they took on years after taking on mine, prejudicing me and my case, lying to me in writing, refusing to return to me that which is mine and which I paid them one hell of a lot of money for, with Klippenstein blaming me for his nastiness after he failed trying to stifle me, including in an Affidavit filed in court and shared with the defendants.![]()

Women are harmed every day by invisible men, When men harm women, we obscure their role. Instead, we blame women for the injustice that happens to them by Rebecca Solnit, March 19, 2021, The Guardian

The alleged murderer of eight people, six of whom were Asian American women, reportedly said that he was trying to “eliminate temptation”. It’s as if he thought others were responsible for his inner life, as though the horrific act of taking others’ lives rather than learning some form of self-control was appropriate. This aspect of a crime that was also horrifically racist reflects a culture in which men and the society at large blame women for men’s behavior and the things men do to women. The idea of women as temptresses goes back to the Old Testament and is heavily stressed in white evangelical Christianity; the victims were workers and others present in massage parlors; the killer was reportedly on his way to shoot up Florida’s porn industry when he was apprehended.

This week an older friend recounted her attempts in the 1970s to open a domestic-violence shelter in a community whose men didn’t believe domestic violence was an issue there and when she convinced them it was, told her, but “what if it’s the women’s fault”. And last week a male friend of mine posted an anti-feminist screed blaming young women for New York governor Andrew Cuomo’s travails, as though they should suck it up when he violated clear and longstanding workplace rules, as though they and not he had the responsibility to protect his career and reputation.

Sometimes men are written out of the story altogether. Since the pandemic began there have been torrents of stories about how women’s careers have been crushed or they have left their jobs altogether because they’re doing the lioness’s share of domestic labor , especially child-rearing, in heterosexual households. In February of this year, NPR opened a story with the assertion that this work has “landed on the shoulders of women” as if that workload had fallen from the sky rather than been shoved there by spouses. I have yet to see an article about a man’s career that’s flourishing because he’s dumped on his wife, or focusing on how he’s shirking the work.

Informal responses often blame women in these situations for their spouses and recommend they leave without addressing that divorce often leads to poverty for women and children, and of course, unequal workloads at home can undermine a woman’s chances at financial success and independence. Behind all this is a storytelling problem. The familiar narratives about murder, rape, domestic violence, harassment, unwanted pregnancy, poverty in single-female-parent households, and a host of other phenomena portray these things as somehow happening to women and write men out of the story altogether, absolve them of responsibility – or turn them into “she made him do it” narratives. Thus have we treated a lot of things that men do to women or men and women do together as women’s problems that women need to solve, either by being amazing and heroic and enduring beyond all reason, or by fixing men, or by magically choosing impossible lives beyond the reach of harm and inequality. Not only the housework and the childcare, but what men do becomes women’s work.

Rachel Louise Snyder in No Visible Bruises, her 2019 book on domestic violence, noted that the framework is often “why didn’t she leave?” rather than “why was he violent?” Young women affected by street harassment and menace routinely get told to limit their freedoms and change their behavior, as though male menace and violence was just some immutable force, like weather, not something that can and should change. And sure enough in the wake of Sarah Everard’s alleged kidnapping and murder by a policeman a few weeks ago, the Metropolitan police went knocking on doors and telling women in south London not to go out alone.

When it comes to abortion, unwanted pregnancies are routinely portrayed as something irresponsible women got themselves into and that conservatives in the US and many other countries want to punish them for trying to get out of. (You get the impression from anti-abortion narratives that these women are both the Whore of Babylon when it comes to sexual activity and the Virgin Mary when it comes to conception.) Though people who want to be pregnant may get pregnant on their own, with a sperm bank or donor, unwanted pregnancies are pretty much 100% the result of sex involving someone who, to put it simply, put his sperm where it was likely to meet an egg in a uterus. Two people were involved, but too often only one will be recognized if the pregnancy ends in abortion.

Katha Pollitt noted in her 2015 book on abortion that 16% of women have experienced “reproductive coercion” in which a male partner uses threats or violence to override their reproductive choice and 9% have experienced “‘birth control sabotage’, a male partner who disposed of her pills, poked holes in condoms, or prevented her from getting contraception”. One of the arguments for why abortion should be an unrestricted right is: violations resulting in conception needs to be counterbalanced by choices over consequences.

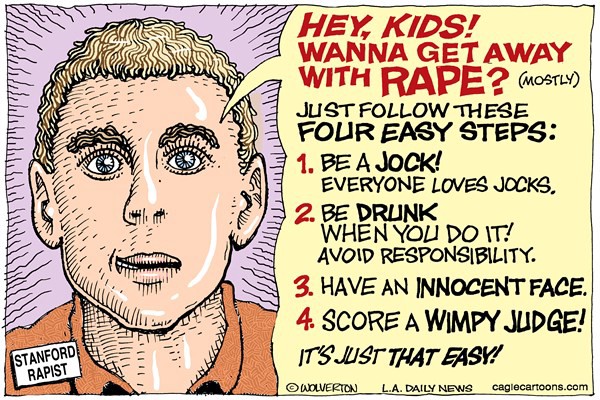

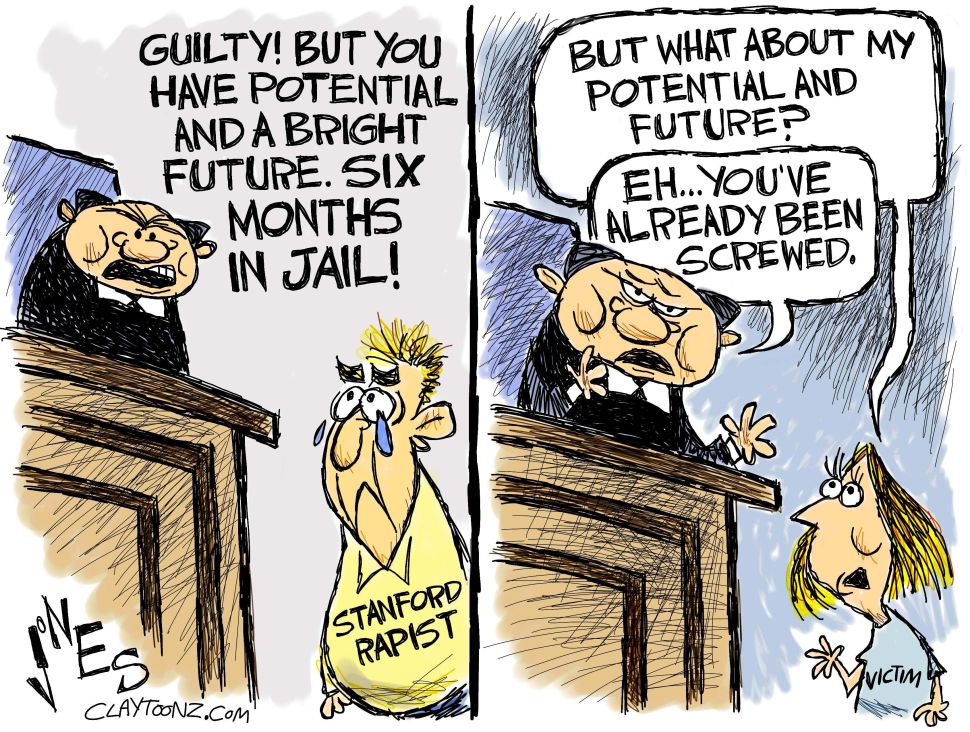

And of course anti-abortion laws with rape exemptions require pregnant people to prove they were raped, an onerous, intrusive, protracted process that often fails anyway, while Pollitt points out how many unwanted pregnancies result from violations of bodily self-determination that falls short of legal definitions of rape. Rape itself is a crime in which the victim rather than the perpetrator is often held responsible. In her stunning memoir Know My Name, Chanel Miller writes about all the ways she was blamed for being, while unconscious, sexually assaulted by a stranger – “the Stanford swimmer rapist”. Likewise, the legal consequences of his actions were framed as things she was inflicting on him.

When Tulane University reported in 2018 that 40% of female and 18% of male students had been sexually assaulted, almost nothing was said about the fact that this meant that they not only had a campus populated by victims, but by perpetrators. In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put out a chart warning women that alcohol consumption could result in being raped, impregnated, battered or infected with an STD, as though alcohol itself could and would do all these things, and women alone were responsible for preventing them. Once again men were extracted from narratives in which they are the protagonists.

There are more subtle forms of blaming the victim, including all the ways that people impacted by abusive and discriminatory situations are portrayed as disruptive or demanding at one end of the spectrum and mentally ill at the other. This happens, of course, when those in charge of the status quo decide to protect it rather than those it harms and marginalizes, a decision that makes reporting harm or marginalization likely to lead to more of same.

Ruchika Tulshyan and Jodi-Ann Burey wrote in February: “Impostor syndrome directs our view toward fixing women at work instead of fixing the places where women work.” That is the diagnosis is too often “has subjective feelings of not being deserving or qualified” when it should be “works in a place that treats her as undeserving or unqualified”. The headline of a 7 March related story shows how this plays out: “Google advised mental health care when workers complained about racism and sexism” and describes how employees making those complaints were pushed out, the people who gave them grounds to complain apparently left unchecked.

Writing perpetrators out of all these narratives means that while the narratives pretend to have concern for victims, victims are not who they’re protecting. Perpetrators are, both as individuals and as a class. This is a problem and even a crisis in all of the situations I’ve described, but in the bloodbath in Georgia it was deadly: a young man learned from his Southern Baptist subculture that sex was a sin and women were temptresses and seductresses, held them responsible for his inner life, and punished them with death.

- RebeccaSolnit is a US Guardian columnist. She is also the author of Men Explain Things to Me and The Mother of All Questions. Her most recent book is Recollections of My Nonexistence

Refer also to:

Cartoon below: “If only things had happened this way.”