Appointment of Russ Brown extends Harper’s influence on Supreme Court by Sean Fine, July 27, 2015, The Globe and Mail

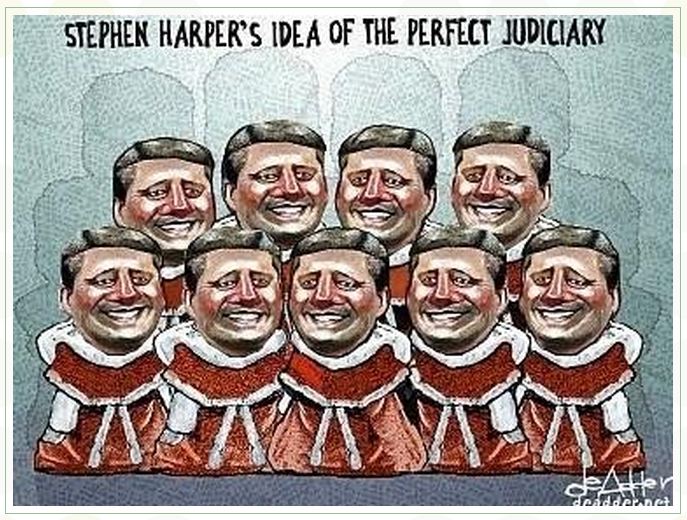

Prime Minister Stephen Harper has named Russ Brown, a conservative judge from Alberta, to the Supreme Court of Canada – the third appointment in 15 months to the country’s most powerful court without parliamentary involvement.

In his early 50s, Justice Brown gives Mr. Harper the possibility of a quarter-century of influence on the court. Some see him as a future chief justice when Alberta-born Beverley McLachlin reaches the mandatory retirement age of 75 in four years.

With a doctorate in juridical science from the University of Toronto, Justice Brown has been fast-tracked by the Conservative government. He was associate dean of the University of Alberta law school when the government appointed him in February, 2013, along with another rising conservative star, lawyer Thomas Wakeling, to the Court of Queen’s Bench. Just 13 months later, the two were promoted again to Alberta’s top court, the Court of Appeal.

The married father of two is a former member of the advisory board of a conservative legal group in Alberta, the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms. Its website says its core views include a belief in “economic liberty,” including property rights as part of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms – which has never been accepted by the Supreme Court. It also says equality before the law means “special privileges for none,” which also runs counter to the Supreme Court’s view that the Charter’s equality clause is primarily for individuals from historically disadvantaged groups and its second part permits affirmative action for the disadvantaged.

“Current events remind us that the notion of limited government – particularly as it pertains to freedom of conscience and freedom of expression – can never be taken for granted in Canada,” Justice Brown said in a website endorsement of the JCCF and its executive director, John Carpay, a former candidate for the Wildrose Party in Alberta.

His endorsement appeared to have been removed from the website Monday evening.

***

[The endorsements before they were changed on Monday, July 27, 2015:

Endorsements

“This is a critical time in Canada, and we need to draw attention to the erosion of freedom in Canada, particularly on campus. It’s good to have the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms there to ensure the rights of all students are upheld.”

– Andrea Mrozek, Executive Director, Institute of Family and Marriage Canada

“John Carpay’s fight for the individual liberties of Canadians is of the utmost importance and should be supported by all those who care about the future of Freedom.” –

– Michel Kelly-Gagnon, President and CEO, Montreal Economic Institute

“I have great confidence in John Carpay’s leadership abilities to build the new Justice Center for Constitutional Freedoms into a formidable organization to defend Canadians’ right to free speech against censorship, especially in universities.”

– Clive Seligman, President, Society for Academic Freedom and Scholarship

“For many years, Canada has desperately needed an organization to properly defend freedom of speech. At long last, we have just that: the Justice Centre and its talented leader, John Carpay.”

– Michael Taube, columnist and former speechwriter for P.M. Stephen Harper

“John Carpay has an impressive track record of commitment to the constitutional rights of Canadians, and with his leadership I am confident that the Justice Centre will be successful in achieving its goals. A free society will always need to be defended against those who wish to limit the rights which we enjoy. The Justice Centre brings another voice for freedom to the Canadian scene, and we can never have too many of those.”

– Matt Bufton, Executive Director, Institute for Liberal Studies

“Current events remind us that the notion of limited government – particularly as it pertains to freedom of conscience and freedom of expression – can never be taken for granted in Canada. More help is needed to preserve these rights. Because John Carpay has a demonstrated record of effective advocacy in just such matters, I expect that the Justice Institute will quickly

join the ranks of Canada’s most important watchdogs.”

– Dr. Russell Brown, Faculty of Law, University of Alberta

“Free speech is the most important freedom. All of our other freedoms, such as freedom or religion and the right to vote, depend on it. Canada desperately needs the Justice Centre’s commitment to free speech, and Canadians of all political stripes should support it.”

– Ezra Levant, author, columnist and free speech activist

“Free association and free speech are the foundation of democracy. Without them, accountable government is not possible. Far too many Canadians assume these rights are protected when in fact they are being eroded. It’s urgent that Canadians support groups and leaders that go beyond the usual platitudes and begin to meaningfully champion these principles that are fundamental to the human spirit. John Carpay’s leadership and contribution on these important issues is unassailable.”

– Troy Lanigan, President and CEO, Canadian Taxpayers Federation

“John Carpay is one of this country’s stoutest defenders of our individual liberties.”

– Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, Macdonald-Laurier Institute

“The Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms is a new and welcome institution, especially dedicated to the defence of free speech at universities. At first thought this is a curious idea, as free thought and speech is of the essence of the university ideal. Unhappily political correctitude can on too many occasions subvert this ideal, and a watchdog is needed to defend those students and even professors who cannot afford to defend themselves. Founder John Carpay has a demonstrated, vigorous and successful track record in this regard.”

– Gordon Gibson, Senior Fellow, Fraser Institute

The Endorsements after they were changed on July 27, 2015

*** ]

Justice Brown could not be reached for comment. …

Deborah Hatch, Past President of the Criminal Trial Lawyers’ Association in Alberta, said the appointment is welcomed by both the defence and Crown prosecutors.

“I have appeared many times before Justice Brown and have always been impressed by his thoughtfulness, his keen intellect, his sense of fairness and restraint, and his respect for and understanding of judicial discretion,” she said in an email. “He is definitely worthy of a position as important to a parliamentary democracy as a seat on the Supreme Court of Canada.”

An Alberta source said he has the respect of other judges for being a hard-working, excellent judge with a strong personality. “Nobody’s going to push him around down there,” the source said of Ottawa. “He’s a good guy but he’s strong.”

A criminal defence lawyer, Brian Hurley, said his impression of Justice Brown is that he is a balanced, thoughtful, academically minded judge. “The left-wing defence lawyers I know breathed a sigh of relief,” expecting a more right-wing judge to be chosen.

The Prime Minister’s announcement does not say whether Justice Brown is bilingual – though Canada does not require that of its Supreme Court judges.

By convention, the appointment was to be made from a Western province. Some in Saskatchewan hoped that province would be tapped because it has been decades since the last judge from Saskatchewan, Emmett Hall, retired from the Supreme Court in 1973.

Justice Brown served as the thesis supervisor for John Rooke, Associate Chief Justice of the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench, when as a sitting judge he obtained his master’s from the University of Alberta. Justice Rooke had political connections to the Harper government, and the experience would have helped Justice Brown earn the government’s trust.

Mr. Harper promised to bring in parliamentary hearings for new appointees to the Supreme Court – and he did, in 2006, for Justice Marshall Rothstein of Manitoba, his first appointee. But after The Globe and Mail revealed his secret short list of candidates from which he made the failed appointment of Justice Marc Nadon in 2013 (the Supreme Court said Justice Nadon lacked the legal qualifications to join), the government cancelled the hearings and Parliament’s involvement in the selection process. Since then, justices Clément Gascon and Suzanne Côté from Quebec and now Justice Brown have been chosen without parliamentary involvement.

Justice Brown’s specialty is economic loss in tort law. He replaces Justice Rothstein, a conservative member of the court who specialized in commercial law. The replacement will not alter the balance between conservative and liberal members of the court. Mr. Harper has appointed all but two members of the nine-person court. [Emphasis added]

One of the commentss:

Alceste 5 hours ago

1. Mr. Justice Rothstein, Stephen Harper’s first appointment in 2006, and a distinctly conservative Supreme Court Justice reaches retirement age in December this year – after the federal election. He chose to retire 4 months early – before the election. This is unprecedented in Canada, but done fairly often in the US.

2. The tradition (not the law) is for two SCC justices from the 4 Western provinces, by rotation. At the moment, we have McLaughlin from British Columbia and the retiring Rothstein from Manitoba – who had replaced John Major from Alberta (1992 to 2005). As the article points out, the last Saskatchewan SCC justice was Emmett Hall, who retired in 1973. It was clearly Saskatchewan’s turn. Harper has broken tradition to appoint another justice from Alberta.

3. Russ Brown was fast-tracked from the University of Alberta to trial judge to court of appeal to Supreme Court of Canada in 2 years and 5 months.

4. As the article states, while a law professor, Brown was a member of the advisory board of the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms. The Centre has only ever intervened in two legal cases, both in support of Trinity Western University in its disputes with the Law Societies of Ontario and Nova Scotia. (both actual hearings took place a year after Brown had ceased being a member.)

Not a promising appointment.

Supreme Court unfair to Harper government, new Ontario justice says by Sean Fine, July 26, 2015, The Globe and Mail

The newest judge on Ontario’s top court has an explanation for the Conservative government’s well-known losing streak at the Supreme Court of Canada: The court’s reasoning process is unfair, making it almost impossible for the federal government to defend its laws, such as those involving assisted suicide, prostitution and the war on drugs.

Ontario Court of Appeal Justice Bradley Miller, whose appointment was announced last month, is part of Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s vanguard on the bench – a leading dissenter, along with fellow appeal-court Justice Grant Huscroft, from much of what Canada’s judges have said and done under the 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

… Justice Miller and Justice Huscroft offer an approach that is more deferential to government than is currently the norm on Canadian courts. If over time they are able to point the court in a new direction, judges will become less likely to strike down laws in which broad moral issues are at stake; government would be given more respect as the authority to decide such issues.

Justice Miller also brings a passionate voice for freedom of religion, arguing that the right to morally disapprove of gay marriage is vital to freedom of conscience. Justice David Brown, appointed to the appeal court last December, makes a similar argument.

But Justice Miller’s most important effect on the law could be on the interpretation of the right to life, liberty and security in Section 7 of the Charter of Rights. This was the section used by the Supreme Court to strike down a ban on assisted suicide this year and prostitution laws (2013), and to reject the government’s attempt to close Insite, a Vancouver clinic where illegal drug users shoot up in the presence of nurses (2011).

A judicial “blind spot” explains the government’s losing streak in those three cases, Justice Miller said in his published work as a law professor. (As a lawyer, he represented the Christian Legal Fellowship in arguing at the British Columbia Supreme Court against physician-assisted suicide.)

Canadian judges have become blind to certain kinds of harm – harm to important principles and harm to culture, he said. They understood such broad social harms in the 1990s, when the Supreme Court allowed criminal laws on hate speech and pornography to stand, he said.

A bit of background on the Charter is necessary to understand Justice Miller’s argument that the court’s approach to Section 7 is unfair to government.

The Charter’s very first section allows government to put “reasonable limits” on rights, if it can show that the limits are justified “in a free and democratic society.” But the court has never allowed an infringement of the Section 7 right to life, liberty and security to stand. The reason is to be found in the wording of Section 7: Any limits have to be in accordance with “the principles of fundamental justice.” It would be illogical to say a government could violate a principle of fundamental justice in a free and democratic society.

The result, according to Justice Miller, is a drastically unfair approach.

“The Court remains entirely focused on the rights-holder,” such as a sex-trade worker, he wrote in an essay last year published on a British constitutional blog. “Justice and justification are to be considered from one side only. All other considerations are to be postponed to the second stage [Section 1] that never comes.”

Thus, he says, it is “profoundly difficult” for the federal government “to articulate the reasoning behind much criminal legislation.” Courts do not perceive the harm done by removing the prohibition against intentional killing in the assisted suicide case, he said in a 2012 interview with Cardus, a Christian think tank with offices in Canada and the United States.

He underlined that point in an interview with Western Law Alumni Magazine two years ago, explaining the success of Vancouver lawyer Joseph Arvay, who represented the individuals seeking the right to a doctor’s help in ending a life.

“Joe’s success – and he does this better than anyone – depends on persuading the court that his client’s personal drama is of the utmost significance, and that those persons who will be stripped of the law’s protection in order to accommodate Joe’s clients just don’t matter all that much.” (Mr. Arvay said at the time that he tries to show it isn’t necessary to trounce his clients’ rights to protect the rights of others.)

Carissima Mathen, a law professor at the University of Ottawa, offered another perspective on the courts’ approach to life, liberty and security. “Arguments extending beyond the right holder are certainly considered,” she said in an e-mail. “They just come up earlier in the process, when thinking about ‘fundamental justice,’ which is really Section 7’s core guarantee.”

She added that in the prostitution, assisted suicide and supervised-injection cases, the law’s impact was severe. “If you have horrific suffering or risk of death on one side, you’re going to need really strong arguments on the other. And it’s probably true that symbolic purposes (such as simply promoting a certain moral vision) are not going to make the cut. But I think that is actually a strength, and not a weakness, of the Charter.”

Justice Miller is a proponent of “natural law” – the idea that universal, unchanging moral principles are inherently human, and form the true underpinnings of law. Iain Benson, a lecturer visiting his law school at the University of British Columbia, introduced him to the philosophy and gave him a book by Canadian philosopher George Grant called English-Speaking Justice. (Justice Miller went on to obtain a doctorate in law at Oxford under a leading natural-law philosopher, John Finnis.)

The George Grant book described the contemporary West as having “lost our confidence in speaking about what is good for human beings,” Mr. Benson said in an interview from France, where he lives. “He actually refers to it as ‘the terrifying darkness that has fallen on contemporary justice.’” Justice Miller, he added, offers “a set of insights that the system desperately needs.”

On gay marriage, Justice Miller’s main themes come together – that government has the right and duty to protect society from harm to its natural moral principles.

“Natural is code for Catholic values with Brad,” in which sex between same-sex individuals is seen as unnatural, or sinful, University of Toronto law and philosophy professor David Dyzenhaus said.

Justice Miller says government is obliged to protect marriage between a man and a woman. “In the same way that government is obligated to steward the political community’s forests, fresh water and other resources, it is obligated to identify the morally valuable aspects of a national culture and its morally valuable institutions and to preserve them from one generation to the next,” he wrote in a 2011 paper, “Sexual Orientation and the Legal Regulation of Marriage.”

“There would seem to be no reason why this obligation to protect a political community’s cultural property should not extend to protecting a morally valuable concept and culture of marriage.” [Emphasis added]

Some comments to the above article:

Nick Wright 2 hours ago

This was to be expected.

Harper poisoned our Senate by appointing greedy, self-seeking people to undermine it in the eyes of the public, and robbing it of its “sober second thought” function by co-opting it as a political arm of his PMO.

He poisoned our electoral system by changing the voting and election spending rules to favour his party, and by taking away Elections Canada’s ability to investigate his party’s election dirty tricks.

He poisoned our criminal justice system by legislating revenge over rehabilitation, and by putting more people in the criminal training school for longer periods of time.

Now he is poisoning our judiciary by establishing fundamentalist evangelical Christian morality as the basis for interpreting our constitution, and by appointing judges who believe that the government of the day has the power to legislate public morality on that narrow basis.

It will take a long time to undo the harm he and his primitives have done–if it can be undone at all; there are no guarantees. The first step in recovery, however, is to remove the source of the poison. October can’t come quickly enough.

iski99 1 hour ago

Thanks for saying it so well.

Harper has taken all that is wrong with the American system and imported it.

It came from Ottawa 18 minutes ago

Amen

…

sepchris 2 hours ago

I do not understand why the self-styled ‘Christian’ right feels so threatened by the Supreme Court standing up for the rights of all Canadians that they have to go to such lengths to prevent it. As a Christian myself, I feel my job is to be the best human being I can possibly be, and since this is a full-time job, I don’t have time to worry about how others are behaving, nor the energy to stand in judgement of their life choices.

Profundis 1 hour ago

May I say, “Amen.”

Nick Wright 48 minutes ago

Well said, and thanks.

Profundis 1 hour ago

I was interested in the newly-appointed Justice Miller’s reasoning, at least for the sake of argument — now having read it twice, I’m stunned by how weak and narrow it truly is.

No, we are not bound in 21st century society by George Grant’s view of “natural” law, especially since great philosophers through the centuries have disagreed about its definition and even its very existence. People who use the word “natural” tend to mean “traditional” and they tend to be conservative.

And no, the insecurity and distaste that some citizens or even many feel for marriage in the gay community is hardly a matter to be protected or sanctioned by law; neither is it remotely equivalent to the very real and hateful prejudice that community endures still. I suppose, in the end, the views of this Harper appointee are disappointing but not surprising.

It came from Ottawa 13 minutes ago

It gets worse the more I read about this Harper appointee. Well past time to heave Steve.

noremacnai1 3 hours ago

From the dates of some of his opinion papers this guy has been applying to become a conservative judicial appointment for some time. Harper bought his stuff. Now if he wants to go to the Supreme court he needs two things, (1) continuing conservative government, and (2) some opportunities to fall on his sword, while on the Court of Appeal, on behalf of that portion of “natural” law that the PCs like. What’s going to be interesting seeing how he splits hairs when “hard to articulate” natural law comes up against what the PCs are promoting. His whole approach is that a national government with a majority should be able to cherry pick its attempts to preserve “natural” while resolutely ignoring natural law when the political grease goes the other way. Like for instance, stewardship of the environment. It will be hard to show how the “law” is supposed to preserve “natural” order when “natural” order is discarded by political whim. In the meantime, there he is saying that a discussion of the constitution should be allowed to be inarticulate.

Thierry 1 hour ago

You must be kidding. A Harper appointed judge licks the boots of the guy who appointed him and that makes the news.

Maybe the SCC justices rule against the Cons because they take seriously their role in upholding the law for all Canadians.

OldITGeek 3 hours ago

Another Harper guy complaining that the Harper appointees are mean to Harper.

Jimbo5 1 hour ago

I call hogwash on the opinions of these two judges. If governments, and not just the Harper government, were more responsive to the direction of the broader society and tackled problems head on with applicable legislation they might not run afoul of the Supreme Court. The SC decisions that have gone against the Harper government are saying loud and clear “You’re decisions are running years behind where the bulk of society has moved on gay marriage, assisted suicide, Insite drug injection, First Nations, etc.

petpieve 45 minutes ago

How can a secular country like Canada be expected to tolerate judges who can’t seem to separate church and state. When a judge has convinced himself that he knows absolutely what is right and what is not and what is natural, how can he possibly judge in an open-minded, unbiased way. Imagine, just to get my point, if a judge was appointed who happened to be personally fond of Sharia Law and wasn’t able to set his personal preferences aside while judging. Could we be expected to tolerate that as well?

antoine111 18 minutes ago

God deliver us from Harpo and Harpo’s opinionated antediluvian appointees.

Stephen Harper’s courts: How the judiciary has been remade by Sean Fine, July 24, 2015, The Globe and Mail

The judge looked down at the full-bearded young man who sat relaxed and smiling before him. Omar Khadr, a former teenage terrorist, was in a Canadian courtroom for the first time.

Years earlier, through various channels, the judge had lobbied Prime Minister Stephen Harper for a promotion – and got one. Part of his new job was assigning cases, sometimes to himself. Now, in 2013, the case before him involved an individual in whom Mr. Harper had expressed an emphatic interest. In the end, Associate Chief Justice John Rooke of the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench ruled for the government and against Mr. Khadr, deciding he had been convicted as an adult, not a juvenile.

No one, including Mr. Khadr’s defence lawyer, said the judge was in any way biased or unfair. But some familiar with the judge’s lobbying said the appearance was unfortunate – that justice must also be seen to be fair.

The Rooke episode is one glimpse of a much bigger, untold story.

… “Dripping blue ink into a red pot,” is how one Alberta Conservative who has been involved in the appointment process described it. In the public glare of Parliament, the Conservatives have passed dozens of crime laws that reduced judges’ power to decide on a sentence. Behind closed doors, the government has engaged in an effort unprecedented since 1982, when the Charter of Rights and Freedoms took effect: to appoint judges most likely to accept that loss of discretion – the little-noticed half of Mr. Harper’s project to toughen Canadian law.

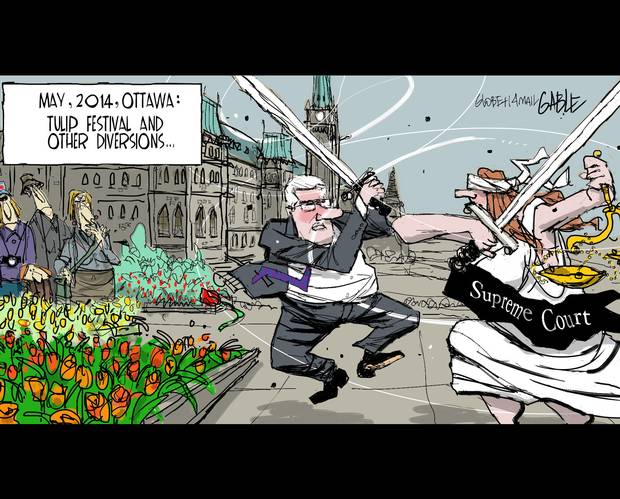

Mr. Harper’s battles with the Supreme Court are well known. The court has struck down or softened several of his crime laws. When the Prime Minister named an outspoken conservative, Marc Nadon, to the Supreme Court in 2013, the court itself declared Justice Nadon ineligible. Mr. Harper would go on to publicly assail the integrity of Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, turning an institutional dispute into a very personal battle – another Canadian first.

But while those public conflicts were playing out, the government was quietly transforming the lower courts. The Conservative government has now named about 600 of the 840 full-time federally appointed judges, or nearly three in every four judges on provincial superior courts, appeal courts, the Federal Court and Tax Court.

These are the courts that, at the appeal level, decide how the government’s crime crackdown is to be implemented. At the trial level, they decide high-profile cases like Mr. Khadr’s. In constitutional cases, they rule on what are called social and legislative facts – anything that establishes the real-world context in which a law plays out, such as whether prostitution laws endanger sex workers. Higher courts, including the Supreme Court, do not change these facts, unless they view them as wildly wrong. Constitutional rulings depend on these facts.

The judges, who can serve until they are 75, may be sitting long after other governments have come along and rewritten the laws. They also are a farm team or development system for the Supreme Court. They are Mr. Harper’s enduring legacy.

In the course of this transformation, entire categories of potential candidates, such as criminal defence lawyers, have been neglected; prosecutors and business attorneys have been favoured.

So cumbersome is the system of political scrutiny that vacancies hit record-high levels last year. And sometimes, critics say, judges and politicians, even cabinet ministers, have come into close contact in the appointment process, raising questions about neutrality and fairness.

Underlying the appointments issue is a covert culture war over who gets to define Canadian values, Parliament or the courts, and what political party puts the most indelible imprint on the nation’s character.

The rules in the appointments system are few, and all previous governments have used the bench to reward party faithful. But Mr. Harper is the first Prime Minister to be a critic of the Charter, and early on he told Parliament that he wanted to choose judges who would support his [irrational and contrary to facts] crackdown on crime.

The Globe spent months exploring the secret world of appointments to understand the extent of the changes and how the government set out to identify candidates who share its view of the judiciary’s proper role. We spoke to dozens of key players – political insiders, members of judicial screening committees, academics, judges and former judges – often on a condition of anonymity, so they could talk freely.

Neither Mr. Harper nor his justice minister, Peter MacKay, would grant an interview.

Chopping at the living-tree doctrine

The appointments system has five steps, four of them political. The first – screening committees spread across the country – is intended to be neutral and independent. Its members originally consisted of lawyers nominated by law societies, bar associations, provincial governments and the federal government, and a provincial chief justice or other judge. In 2006, the Conservative government added a police representative, and took away the judge’s vote – ensuring that federal appointees had the voting majority on the committees.

Next, cabinet ministers responsible for patronage appointments in their regions make recommendations, chosen from the committees’ lists, to the justice minister. The minister’s judicial affairs adviser scrutinizes those picks, and the minister sends his choice to the Prime Minister’s Office for review. Finally, cabinet decides.

Long before he became prime minister, Mr. Harper made it clear that he objected to the judiciary this system produced, and that the deck was stacked against his [anti-charter] view of constitutional rights. A Liberal prime minister, Pierre Trudeau, was the driving force behind the Charter. He made the first Supreme Court appointments of the Charter era, choosing liberal judges such as Brian Dickson and Bertha Wilson, who were determined that the Charter would make a difference in Canadians’ lives.

Gay rights were a flashpoint. In 2003, as Canadian courts began to legalize gay marriage, Mr. Harper, then opposition leader, hired Ian Brodie as his assistant chief of staff. Mr. Brodie, at the time a political scientist at the University of Western Ontario, had just published a book in which he decried “judicial supremacy” – the notion that Supreme Court judges had usurped the role of Parliament.

Originalism holds that constitutions mean what their drafters said they meant, and don’t change with the times [Or used to keep fascist, racist, cruel-spirited, misogynistic dictators (that appoint believers/promoter of originalism into positions of power) happy?]

At Western, Mr. Brodie teamed up with Grant Huscroft, a young law professor who would go on to organize conferences, write articles and edit books to give life to U.S.-style “originalism,” which holds that constitutions mean what their drafters said they meant, and don’t change with the times. This is the philosophy of Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, the most conservative U.S. Supreme Court justices.

That year, Mr. Harper made a daring accusation, based on originalism, in the House of Commons. The Charter’s framers deliberately did not protect gays and lesbians in the equality clause, he said. Therefore, the Supreme Court, which had read such protection into the Charter back in 1995, had violated the Constitution, he argued. And now, in 2003, that decision had become the legal foundation for gay marriage. “I would point out that an amendment to the Constitution by the courts is not a power of the courts under our Constitution,” he said.

Mr. Harper was challenging a status quo rooted in modern women’s rights. In 1928, the Supreme Court ruled that women could not be appointed to the Senate because they were not “persons” – they did not vote or run for office in 1867, when the country’s founding Constitution was written. But the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in England said on appeal that the Constitution should be seen as a “living tree capable of growth and expansion within its natural limits.” Women were indeed persons, because constitutional interpretation changed with the times.

The living-tree idea has been at the heart of Charter legal rulings since the beginning: It has not been a matter of dispute on Canadian courts. The Supreme Court has rejected originalism in several rulings, including the landmark same-sex marriage case of 2004.

But to Mr. Harper and his circle, the living tree means rule by judges. “We have in very significant measure ceased to be our own rulers,” Conservative MP Vic Toews told a pro-life group in Winnipeg in 2004, after quoting from a book by conservative U.S. jurist Robert Bork.

[Is Vic Toews (Vic Toews gets the patronage appointment he waited his whole life for) credible (Vic Toews: Election-law violator becomes top lawmaker) after the illegal stunts he’s pulled?]

Two years later, Mr. Toews became the first justice minister in the new Conservative government. He quickly revamped the appointments process, giving the government its voting majority on the screening committees. A furor erupted. The country’s chief justices complained that judicial independence was at risk.

Mr. Harper did not back down. He got to his feet in the House of Commons and said something no prime minister in the Charter era had ever said publicly. He declared that his government wished to appoint judges who saw the world in a certain way – that is, those who would be tough on crime.

“We want to make sure that we are bringing forward laws to make sure we crack down on crime and make our streets and communities safer,” he said on Feb. 14, 2007. “We want to make sure that our selection of judges is in correspondence with those objectives.”

But even with voting control on the screening committees, the Conservative government’s choices were constrained. There were few proponents of originalism like the Americans’ Justice Scalia, who dissented bitterly from last month’s landmark gay-marriage ruling and as late as 2003 supported a state’s right to criminalize homosexual sex. There was nothing like the Federalist Society, a grassroots national movement in the U.S. that encourages young lawyers to promote conservative views and support the doctrine of original intent. There was no single defining political issue like abortion. In the U.S., judicial conservatism is much more about activism – judges trying to roll back precedents such as Roe v. Wade, which established women’s right to abortion on demand, or to reject gun controls, or limit affirmative action policies.

In Canada, judicial conservatism tends to mean judges who accept the wishes of legislators – judges who defer to Parliament’s primary role as lawmaker and are reluctant to find fault with a government’s choices. Judges who know their place.

Finding reliable judges

The key to the Conservative strategy is identifying prospects with the right views. The Prime Minister has eyes and ears across Canada.

These belong to the cabinet members responsible for dispensing patronage appointments (known as political ministers). They use their local contacts, such as party fundraisers (or “bagmen”) to identify lawyers, academics and sitting judges who fit their specifications, and recommend them to the justice minister. Appointments under the Liberals, worked in much the same way: A cabinet minister opened the door.

“You always have to have a champion,” a Conservative from Alberta explained. “Nobody gets appointed without somebody walking them through, in one way or another.”

In Ontario, the political ministers are Joe Oliver in Toronto, Pierre Poilievre in Ottawa, Diane Finley in the southwest and Greg Rickford in the north. Mr. MacKay is the political minister in Nova Scotia. Defence Minister Jason Kenney and Health Minister Rona Ambrose are the political ministers in Alberta. Some political ministers are more intent on identifying conservative-minded candidates for the bench than others. (Strangely, three leading criminal defence lawyers have been appointed on Mr. MacKay’s home turf. What he supported in his own backyard he did not foster in the rest of the country.)

Mr. Kenney has a political office in Calgary separate from his constituency office, with separate full-time staff. Both he and Ms. Ambrose need to sign off on each candidate either one recommends for a judicial appointment, another Alberta source said. “The person has to make it by both Jason and Rona. They both have a veto. In Calgary, there’s generally a respect on Rona’s part for Jason’s picks and vice-versa.”

Mr. Kenney and Ms. Ambrose are not lawyers. They ask their contacts to recommend candidates.

“It’s not, ‘Is this person going to be tough on crime?’ ” the first Alberta source said. “It’s, ‘Can you recommend this person, are they reliable?’ There’s a little bit of code in there.” Reliability means being both right-of-centre and competent – a two-level filter.

Reliability has a more nuanced meaning, too, according to an appeal court judge, not in Alberta, who follows judicial appointments closely: judges who are technically minded and stick to precedent, who won’t “play with the rules or make new rules.”

Finding reliably conservative judges is a challenge. In Alberta, roughly one-third of federal judicial appointees are not right-of-centre, the first source said, but are chosen for being competent and not left-of-centre. The ideological requirement is not a litmus test around a single issue, but around a general worldview involving a lack of sympathy for minority causes or convicted criminals – which some Conservatives see as the demarcation line between right and left.

“You either see a criminal as a victim of society or as someone who needs to pay his debt to society,” the source said. “One’s a little bit to the left, one’s a little bit to the right. You don’t always get that right either when you pick. People sometimes surprise you when they get up there and have no boss other than their own conscience.”

This either-or view of sentencing incenses legal observers such as Allan Wachowich, a retired chief justice of the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench. Mr. Wachowich, a long-ago Liberal “bagman” by his own description, was a Liberal appointee who was named associate chief justice by a Progressive Conservative prime minister, Brian Mulroney. (His champion was cabinet member Don Mazankowski, but he didn’t know until Mr. Mulroney told him, he said. He told the prime minister jokingly that it was all part of a “Polish conspiracy.”) “You have to treat every case as an individual case,” Mr. Wachowich said in an interview. “Is there any hope of redemption? Is there a prison where he isn’t going to be influenced by hard-core criminals? You’ve got to sit there and listen and contemplate, and give it a weekend sometimes.”

About four years ago, at a time when judges had begun striking down Conservative laws on crime and drugs, political ministers such as Mr. Kenney and Ms. Ambrose came under increased pressure to choose judges who would defer to legislators.

“Deference became a buzzword when a number of laws were being struck down, mostly for Charter violations,” said former Conservative MP Brent Rathgeber, now an Independent.

As one of the few lawyers in the Alberta caucus from 2008 to 2013, he was sometimes consulted on appointments by a political minister. “The PMO decided it would be better if we had a judiciary more deferential to Parliament’s authority.” [And Pro-Fascist Anti-Charter?]

In at least one case in Alberta, Mr. Kenney and Ms. Ambrose personally checked out a new candidate for the bench, according to a source familiar with the process. The candidate first attended a series of get-to-know-you breakfasts and lunches with Conservative Party insiders, before a chat with the two ministers, and was ultimately named to the Court of Queen’s Bench, the province’s top trial court, the source said.

There are no written rules prohibiting such contacts between prospective judges and cabinet members or other politicians. A Conservative, who did not confirm that the meeting took place, said there would be nothing wrong if it did, because the appointments are for life and mistakes can’t be undone.

But mention of the meeting often brings a shocked reaction from lawyers and judges, who view it as compromising independence. Peter Russell, a political science professor emeritus at the University of Toronto and a leading expert on judicial appointments, explained the sense of shock.

“Yes, the public should be concerned about partisan interviews of prospective candidates for judicial appointment,” Prof. Russell said. Such interviews mean that, in Canada, “appointments to the highest trial courts and courts of appeal in the province remain open to blatant partisan political favouritism in selecting judges – something most provinces and most countries in the liberal democratic world have reduced or eliminated.”

Both Mr. Kenney and Ms. Ambrose refused to speak to The Globe for this story.

They would not confirm or deny that they interviewed a candidate for the Court of Queen’s Bench. An Alberta source said the appointment process is a matter of practice and tradition. “It’s not even really written down anywhere.”

‘Interested in a promotion? Play with us’

The government’s strategy is to change the judges at the same time as it toughens the Criminal Code. And sitting judges have a record that can be monitored.

Former prosecutor Kevin Phillips of Ottawa had barely taken his seat as a provincially appointed judge in the fall of 2013 when his fellow judges began rebelling openly against a new law. The victim surcharge, a financial penalty used to subsidize victim services, had just become mandatory; even the poorest criminals would have to pay. Judges in several provinces refused to force them. In Edmonton and Vancouver, some judges allowed 50 or even 99 years to pay. In Montreal, a judge found a way to make the surcharge $1.50. An Ottawa judge ruled the law unconstitutional without even giving the government a chance to defend it.

The surcharge was typical of the government’s crime laws: It removed discretion from judges, with a mandatory minimum penalty. It took from criminals and gave to victims.

Instead of joining the rebels, Justice Phillips, a police chief’s son, turned against them. Thwarting the will of Parliament is a “recipe for arbitrariness,” he said in a ruling released eight weeks after he joined the Ontario Court of Justice in Brockville, and “arbitrariness is antithetical to the rule of law.”

His stay on that court didn’t last long: On April 13, four months after Justice Phillips took his public stand, Mr. MacKay announced his promotion to the Ontario Superior Court, the top trial court in the province.

This is not to imply that Justice Phillips is less than fair-minded. As a prosecutor, he received high praise for his fairness from criminal defence lawyers in Ottawa interviewed for this story. But his appointment sent a message to judges on lower courts – those appointed by the provinces. As a veteran lawyer in Toronto put it, “ ‘You’re interested in a promotion to the Superior Court? Play with us.’ ”

A provincial court judge in Western Canada, speaking not about Justice Phillips but generally, says he is concerned that some judges have a “career plan” that involves a promotion.

“I worry that some judges hear the footsteps,” he said. “They read the headline in The Globe and Mail before it’s written, and maybe, just maybe, they temper their judgment as a result. As soon as you get to that stage, the integrity of the system crumbles. But do I think that happens? Yes, I do think it happens.”

The judge, the PM and the promotion

Some judges make their case for promotion directly to politicians – despite a Canadian tradition that usually keeps judges and legislators apart to ensure that the system appears to be, and is, neutral.

On three separate occasions when he was still a Conservative MP, Mr. Rathgeber says judges came to him. “I can tell you of one Court of Queen’s Bench judge and a couple of Provincial Court judges who were seeking elevation to the Court of Appeal and Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench,” he said. “The judge would tell me why they thought they were not a good fit on the Court of Queen’s Bench trial division and why their skill set might be better doing appellate [work] at the Court of Appeal. And if there’s anything I can do to help that occur.”

Some in the legal community view aggressive lobbying by sitting judges as unseemly. Sometimes it backfires. Other times, though, it is rewarded – as appears to be the case with Justice Rooke.

In 2009, the judge on the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench lobbied the Prime Minister through channels for the job of chief justice, multiple sources told The Globe. He put together a dossier on his record. Jim Prentice, then the federal environment minister, spoke to Mr. Harper on Justice Rooke’s behalf. Justice Rooke and Mr. Prentice had been “little Clarkies” – party workers who had supported Progressive Conservative leader Joe Clark decades earlier.

Justice Rooke also reached out personally to well-regarded figures in the legal community who tend to be consulted by the Conservative government in judicial appointments, an Alberta Conservative said.

Some of Justice Rooke’s colleagues resented his lobbying, believing that Neil Wittmann of Calgary, then the associate chief justice, deserved to be chief justice. Justice Myra Bielby, the senior judge in Edmonton, would probably then become associate chief justice. According to a 100-year-old tradition – never broken – if a chief justice was appointed from Calgary, the associate chief was chosen from Edmonton, and vice-versa.

A committee of his colleagues on the bench approached Justice Rooke about a rumour he had even met personally with Mr. Harper. (The Prime Minister appoints chief and associate chief justices.) In the Canadian system, such a meeting would have been seen as irresponsible, and the committee’s approach was a sign that the judges were alarmed by the prospect. Justice Rooke vehemently denied that the meeting took place, which the judges accepted.

But some made known who they felt should be chief and associate chief. “There were a lot of ‘bank shots’ [from Justice Rooke’s colleagues] to make sure that for an appointment like that, you have the right person, because the system has to work,” the source said. To make a bank shot is to have someone else send your message – “you get the justice minister [of Alberta] to make a call, you get the chief of staff to make a call, you get three or four senior lawyers to make a call.”

Mr. Harper named Justice Wittmann, who joined the bench as a Liberal appointment, as chief justice. Then, despite the century-old tradition, he chose Justice Rooke as associate chief. The government later promoted Justice Bielby to fill the first vacancy on the Court of Appeal.

In 2013, Justice Rooke took on the Khadr case. On the day of the hearing, Mr. Harper publicly stated his support for the most severe punishment possible. Politicians rarely comment on cases before a court because it may look like an improper attempt to influence a judge. Still, Justice Rooke said his ruling in favour of the Canadian government – to treat Mr. Khadr as an adult – was a straightforward matter of statutory interpretation.

Six months later, the Alberta Court of Appeal overturned the ruling in a 3-0 vote. Among the three were two Conservative appointees, including Justice Bielby. This spring, the Supreme Court also ruled in Mr. Khadr’s favour – adding insult by deliberating for just a half-hour.

No one has suggested that Justice Rooke was unfair, or that there was a quid pro quo for his appointment as associate chief justice. Dennis Edney, an Edmonton lawyer who represented Mr. Khadr, said he found the judge “attentive and fair in his dealings with me and my representations. That is all I ask.”

To some Conservatives, the appointment of Neil Wittmann ahead of John Rooke showed that ability matters more than politics in Conservative appointments. “It’s a very, very good example to show where skill and talent and colleagues’ confidence trumped political bias,” a party source said.

But to outside observers, when judges lobby for promotions, they undermine the appearance – and perhaps the reality – of judicial independence.

“If you’re starting to get into a lobbying process, are you not then beholden to those who make the appointment?” said John Martland, a former president of the Alberta Law Society, speaking generally.

The Globe contacted Associate Chief Justice Rooke through his assistant and asked if he wanted to correct any facts or provide comments. Diana Lowe, his executive counsel, replied that judges speak only through their judgments and a response would not be appropriate.

In an ironic postscript to these events, the federal government went before the Alberta Court of Appeal in May to block Mr. Khadr’s release on bail. A single judge heard the case – Justice Bielby.

Mr. Khadr is now free on bail.

Tapping a ‘very small pool’

Because there is rarely a straight line from what an appointing government expects to how a judge actually rules, the Conservative strategy is designed to reduce uncertainty, using broad categories as a convenient shortcut to predicting the ideological orientation of candidates for the bench.

Criminal defence lawyers are underrepresented, according to a Globe and Mail review of all appointment notices since 1984. Academics are, as well, with some notable exceptions. So, too, is anyone who has a senior role in a group with the word “reform” in its title. (One such group is – or was – the Law Reform Commission of Canada, later known as the Law Commission of Canada; in the Conservative government’s first year in power, it scrapped the organization.)

Business lawyers are favoured. Prosecutors are favoured.

Judges appointed by Progressive Conservative prime ministers Mulroney and Kim Campbell look very much like judges appointed by Liberal prime ministers Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin, apart from the underlying political affiliations. They appointed more criminal defence lawyers than prosecutors. They did not shy away from academics, either. And Mr. Mulroney chose leading liberals such as Louise Arbour and Rosalie Abella in Ontario, and Morris Fish in Quebec; Liberal governments later named them to the Supreme Court.

The current Conservative government has appointed few judges in the past nine years who have liberal reformist credentials. Three judges it named to the Ontario Court of Appeal since late in 2012 represented groups arguing against gay marriage at the Supreme Court in 2004. As of this winter, it has appointed 48 prosecutors, compared with 12 lawyers who did primarily criminal defence work, and 10 academics.

Conservatives say the system is no more ideological today than it was under the Liberals. “I can’t see the difference,” a Conservative said. “When someone is a committed federal Liberal and has worked for the party for 30 years and gets to be of a certain age and a certain standing where some political heavyweights recommend them [for the bench], it’s because they’re ideologically framed by working for the party.”

But David Dyzenhaus, a University of Toronto law and philosophy professor, says he is deeply worried by the pattern of appointments.

“It’s very clear that it’s almost impossible for a judge who comes from the political centre or to the left to be appointed,” he said. “Which means that the appointment of judges is from a very small pool of lawyers. That invariably means people of considerable ability are being passed over. The quality of the bench is going to be lower. It will invariably take its toll on the Canadian legal order.”

How to evade ‘lefties’

The screening committees set minimum standards for the selection of judges. Across the country there are 17 such judicial advisory committees (JACs), as they are known, and they are the only stage of the appointment process whose rules are public.

Until 2006, the committees had three choices when presented with a candidate: highly recommend, recommend or not recommended. Mr. Toews changed that, however, stripping out the first option; now committees can only recommend, or not.

The loss of the highly recommended category “removes a lot of the committee’s ability to express to the minister its view as to who really should be appointed to these positions,” said Frank Walwyn, a Toronto business lawyer appointed by the Ontario government to the screening committee in the Greater Toronto Area.

Of the 665 applicants in 2013-14, the committee recommended 300, or nearly one in every two. Of those 300, the government anointed a chosen few – 66 judges, or roughly one in five of the recommended group. Under the last year of the old rules, 2005-6, the committees “highly recommended” 76 applicants; if a government wished, it could find enough highly recommended judges to fill all the vacancies.

In practice, despite the changes that put federal government appointees in the voting majority, the committee members tend to seek common ground. “What I’ve found is that consensus really is the order of the day,” Mr. Walwyn said. “If you have a number of people saying this person is not balanced either in the prosecution or defence of individuals, the committee will take that very seriously.”

From the Conservative government’s perspective, the committees sometimes stand in the way of the judges it wishes to appoint. So the government has taken deliberate steps to evade the committees, at least in Alberta, a local source said. It has a kind of express lane to bypass the need for a committee recommendation: choosing from judges already serving on the Provincial Court, a lower level of court appointed by the province. (The committees comment on these judges, but make no recommendation.) These tended to be right-of-centre judges with a known track record.

The advisory committees “were not letting through tough-on-crime candidates because they wanted some lefties to be appointed,” the source said. “Liberal judges had control of the screening committees. One of the ways [the government] could get around this is if you were already appointed to another court, the screening committee could not block you; they could only comment.” In this fashion, a Provincial Court judge, Brian O’Ferrall, made an unusual leap straight to Alberta’s highest court, the Court of Appeal, in 2011. Several others went to the Court of Queen’s Bench.

This is not against the rules. The appointments system has wide discretion.

The next steps: recommendations from the political ministers, then the judicial affairs adviser checking out the candidates. One such adviser, Carl Dholandas, was a former member of the national Progressive Conservative Party executive who served as executive assistant to Nigel Wright when he was chief of staff in the PMO. The justice ministry declined to make him available for an interview. He left the post early this year, and the ministry would not even reveal the name of the new adviser. (It’s Lucille Collard, who was an official at the Federal Court of Appeal.)

After the Justice Minister’s recommendation goes to the PMO, an appointments adviser, Katherine Valcov-Kwiatkowski, screens the candidates yet again, before a name makes it to a cabinet vote.

This unwieldy process has slowed the system. Chief justices grew restive at the high numbers of vacancies on their courts: at record levels last year – more than 50 open seats. That number plummeted to 14 in June, with an avalanche of appointments before the official start of the federal election campaign. Quebec Court of Appeal judges were stretched so thin last fall that Chief Justice Nicole Duval Hesler asked Superior Court chief justice François Rolland if she could borrow some judges on an ad hoc basis, a source said. Chief justice Rolland said no.

In his annual public address in September, chief justice Rolland complained that one of the vacancies on his court went back to August, 2013, and four others to April, 2014. Civil trials expected to take longer than 25 days must be booked four years in advance, he said. He jokingly asked if anyone could get Justice Minister MacKay on the phone, because he had tried and failed. The judge has now retired.

One seat that was filled: In 2013, an opening on the Manitoba Court of Queen’s Bench went to former justice minister Vic Toews.

The judge who doesn’t like Canadian law

It is easy to see why Mr. Harper would be a fan of Grant Huscroft, Ian Brodie’s friend and co-editor, and why the Conservative government named the Western law professor to Ontario’s highest court, effective in January. (Mr. Brodie, now at the University of Calgary, tweeted his congratulations.)

In his published work, Mr. Huscroft has rejected virtually everything at the heart of the Canadian constitutional order. He is opposed to judges reviewing rights claims under the Charter – an important part of his job. He believes it’s undemocratic and judges are no better than anyone else at deciding whether a law is consistent with the rights commitments of the Charter. He has made the same point as Mr. Harper on gay rights and the Charter – that the framers deliberately did not protect gay rights. He has written that democracies do not “grossly violate rights,” but put “thoughtful” limits on them.

Wil Waluchow, a legal philosopher at McMaster University who strongly disagrees with Mr. Huscroft’s originalism, describes him as open-minded and respectful of different viewpoints. “He may fight against the mainstream to some extent, but I don’t think it will be in a way that is disrespectful or dishonest,” Prof. Waluchow said. “I respect Grant an enormous amount.”

Prof. Dyzenhaus, who co-edited a 2009 book of essays with Mr. Huscroft, is also familiar with his work, and has a somewhat different view. “He’s an attractive choice for Stephen Harper because he shares with Harper an antipathy for entrenched bills of rights and the way of interpreting those rights that Canadian judges have developed for 30 years,” Prof. Dyzenhaus said by phone from Cambridge University, where he is the Arthur Goodhart Visiting Professor of Legal Science.

So why does Mr. Huscroft want to be a judge? In Canada, unlike in the U.S., there is no public review of the federal appointments of new judges in which that question could be asked. Or this one: How can he stay true to his principles while respecting precedent?

Mr. Huscroft declined multiple requests for an interview. But Prof. Dyzenhaus believes Mr. Huscroft hopes to bring change from within.

“If I’m right that he thinks large chunks of the Canadian legal system are illegitimate, one reason for taking office is he wants to get involved in a kind of damage-limitation exercise. So to the extent he can, he will try to prune the living tree.” [Kill the rights of Canadians?]

The constitutional romance

Constitutional romantics assume the worst of elected legislators and the best of judges,” Mr. Huscroft has written. For nearly 10 years, the Conservative government has been dripping blue ink into a red pot – attempting to expunge, bit by bit, the country’s 30-year romance with the Charter, and with judges who go out of their way to be the guarantor of rights.

The moves have produced mixed results. The government is up against a culture of unanimity; when Liberal and Conservative appointees sit down together, they tend to find common ground. It also faces a tradition of judicial independence, as some Conservative-appointed judges have demonstrated in striking down tough-on-crime legislation. “This, irrespective of who appointed you, is always the dominant culture,” one appeal court judge said.

There is no strong evidence, in a statistical sense, of more severe criminal sentencing. But there are other areas of the judicial system where the effects can be seen. Perhaps the clearest sign of change is on the Federal Court. Refugees whose claims are rejected by the immigration board can ask this court to review their case. The review is not automatic, and Conservative appointees on the Federal Court agreed to a review in just 10 per cent of cases, compared with 17.6 per cent for Liberal appointees, a study found. David Near, a former judicial affairs adviser for the Conservatives, accepted 2.5 per cent of requests for judicial review he heard on the Federal Court. In 2013, he was appointed to the Federal Court of Appeal.

As an election approaches that will be fought in part on security from terrorism and crime, the Prime Minister and his cabinet continue their determined effort to reshape the judiciary. In June, they promoted Justice Bradley Miller, another former Western professor and proponent of originalism, to the Ontario Appeal Court. He opposes gay marriage and asks whether the Supreme Court has lost its moral centre. Business lawyers were again prominent, criminal defence lawyers scarce.

Mr. MacKay’s office has given only one answer when The Globe has asked questions over the past eight months about individual appointments and the judicial appointments process: “All judicial appointments are based on merit and legal excellence and on recommendations made by the 17 Judicial Advisory Committees across Canada.” [Is MacKay trustworthy, integral or believable (Legacy of lies)?]

Sean Fine is The Globe and Mail’s justice reporter.

Stephen Harper’s most unfortunate appointments, Nearly a decade of appointing people to positions of power has left Stephen Harper with a number of unfortunate associations by Aaron Wherry, July 2, 2015, McLeans

Arthur Porter, detained in Panama while he fought extradition to face fraud charges in Canada, died yesterday at the age of 59. He had reportedly been suffering from lung cancer.

Porter was the chief executive officer of the McGill University Health Centre from 2004 to 2011, but was accused of being involved in bribery related to the construction of the hospital. In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper appointed Porter to the Security Intelligence Review Committee, the independent body that oversees the Canadian Security Intelligence Service. In 2010, he was appointed to chair the committee, but the next year he resigned from SIRC after the National Post questioned his dealings with an international lobbyist. (In 2013, it was revealed that Bloc Québécois leader Gilles Duceppe had questioned Porter’s appointment in a letter to the Prime Minister.)

It stands to reason that anyone responsible for the appointment of hundreds of people will eventually end up being associated with someone who does something unbecoming. But after nearly 10 years as Prime Minister, Stephen Harper is now tied to a rogues gallery of appointees.

Dean Del Mastro

Appointment: Parliamentary secretary to the Prime Minister, May 2011 to September 2013

Trouble: Last month, Del Mastro was sentenced to one month in prison and four months of house arrest after being found guilty of exceeding the election spending limit in 2008 and submitting a false document.

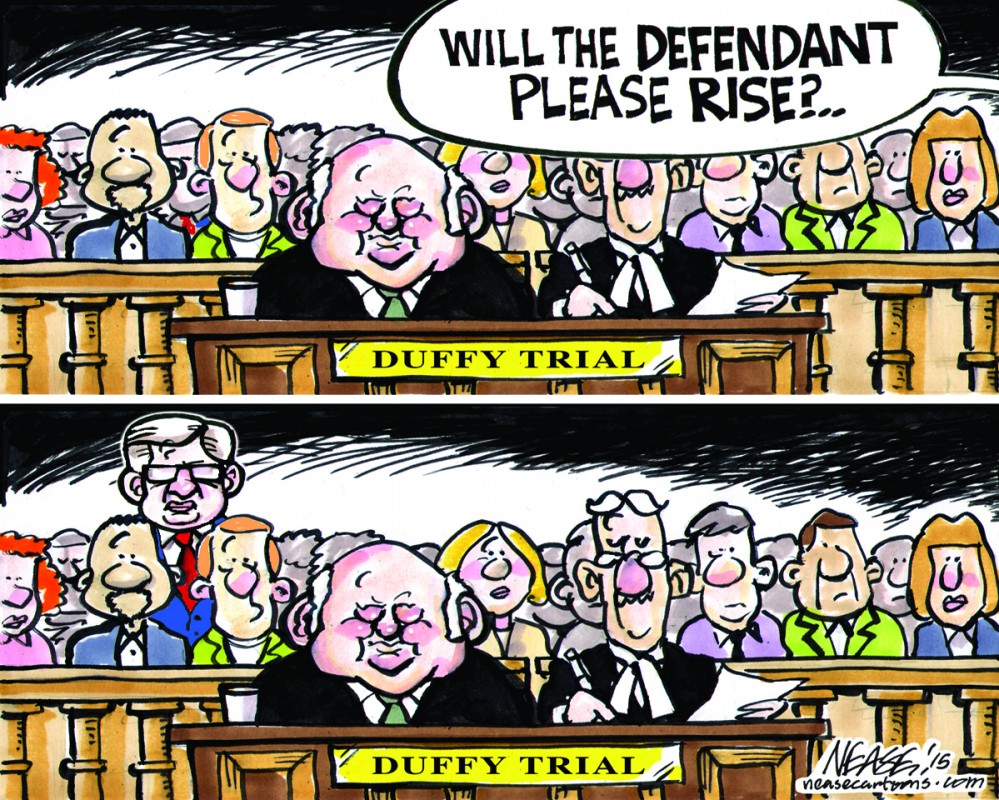

Mike Duffy

Appointment: Senator for Prince Edward Island

Trouble: Currently on trial for 31 charges, including fraud and breach of trust, related to expenses and contracts claimed as a senator. Suspended from the Senate in November 2013.

Pamela Wallin

Appointment: Senator for Saskatchewan

Trouble: At last report, Wallin was being investigated by the RCMP for expenses she claimed as a senator. Suspended from the Senate in November 2013.

Patrick Brazeau

Appointment: Senator for Quebec

Trouble: Charged in March with fraud and breach of trust for expenses claimed as a senator, Brazeau is also on trial for charges of assault and sexual assault. He has also been charged with assault, uttering death threats, cocaine possession and breaching bail conditions as a result of an April 2014 incident. He was suspended from the Senate in November 2013.

Marc Nadon

Appointment: Supreme Court justice

Trouble: After Nadon had been nominated and sworn in, the Supreme Court ruled in March 2014 that Nadon was not qualified to fill one of the seats designated for Quebec on the high court. The affair later culminated in an unusual public dispute between the government and the chief justice.

Bruce Carson

Appointment: Adviser to the Prime Minister’s Office

Trouble: Currently facing charges of improper lobbying and influence peddling.

Nigel Wright

Appointment: Chief of staff to the Prime Minister, September 2010 to May 2013

Trouble: Well-regarded when he was chosen to oversee the Prime Minister’s Office, Wright resigned in May 2013 after it was revealed he had given $90,000 to Mike Duffy to cover the senator’s disputed expenses.

Peter Penashue

Appointment: Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs, May 2011 to March 2013

Trouble: Admitted in March 2013 that his campaign in 2011 had accepted ineligible donations and resigned his cabinet portfolio and his seat. Ran in the resulting by-election, but lost. Earlier this year, the official agent for Penashue’s campaign was charged with violating the Elections Act.

Don Meredith

Appointment: Senator for Ontario

Trouble: Previously questioned about his education credentials, Meredith’s treatment of staff is currently being investigated by the Senate and he was expelled from the Conservative caucus last month after the Toronto Star reported allegations that the senator had had a sexual relationship with a teen girl. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to a brief Ernst vs Encana chronology:

2001: Encana begins a secret experimental shallow fracturing natural gas project arond Rosebud, without consulting with the community or landowners in violation of EUB (now AER) Directive (then Guide) 56.

June 2003: Encana’s first un-attenuated compressor installed about 900 metres from Ernst’s home, without consulting her about it, in violation of Guide 56. The noise was like a jet engine taking off, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Encana continues to violate Ernst’s legal right to quiet enjoyment of her home and land.

February 14, 2004: Encana perforated and on March 2, 2004 illegally hydraulically fractured directly and secretly into the drinking water aquifers that supplies the Hamlet of Rosebud, the Ernst water well and others, and diverted fresh drinking water without the required permit under the Water Act.

April 21 2006: Prime Minister Harper nominates Encana’s Gwyn Morgan as first Chairperson of the Public Appointments Commission

December 3, 2007: Ernst files Statement of Claim in Drumheller Court of

Queen’s Bench

December 3, 2008: Ernst serves the required legal papers on Encana, ERCB, Alberta Environment, Kevin Pilger, Neil McCrank and Jim Reid.

October 24, 2009: Prime Minister Harper announces the appointment of Neil Wittmann as Chief Justice of Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta

April 27, 2011: Ernst goes public with her lawsuit

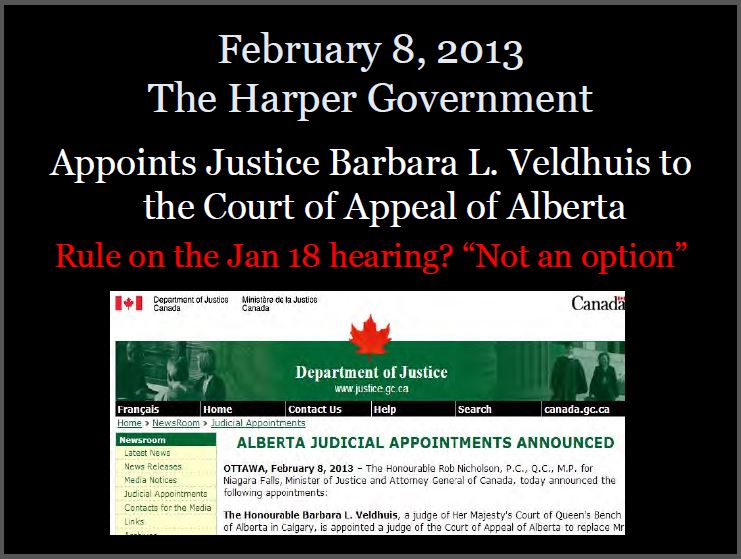

June 24, 2011: Harper Government appoints Barbara Veldhuis to Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta

April 26, 2012: First Ernst vs Encana hearing in Drumheller Court of Queen’s Bench. Justice Veldhuis requests shorter statement of claim and volunteers to be case manager.

October 1, 2012: Defendants demand the Ernst case is moved out of its rightful jurisdiction to Calgary during a case management call with Justice Veldhuis (moving the case was not on the agenda). Lawyer representing the Alberta Government:

“It clearly tips in favour of the defendants’ position, that it ought to be in Calgary and not in Drumheller.”

Justice Veldhuis advised that according to Chief Justice Wittmann, the case is to be heard in Drumheller. Encana lawyer advised they will not drive to Drumheller. The case is subsequently moved to Calgary by Justice Wittmann.

January 18, 2013: Second court hearing heard by Justice Veldhuis in Calgary. The court room is packed, not enough seats, some attendees were directed to an incorrect room, some left because they were unable to get a seat.

February 8, 2013: Harper Government promotes Justice Veldhuis to Alberta Court of Appeal. In a subsequent case management phone call, Ernst’s lawyers asked if Justice Veldhuis would rule on what she had heard in court a few weeks earlier. They were dumbfounded to be told that this was “not an option.”

February 15, 2013: In a case management call with Justice Veldhuis, it was relayed that Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench Neil Wittmann volunteered to take over the case. The other option offered was for the three defendants and plaintiff to come to agreement on a new judge which would have been a long drawn out, expensive and unjust process for Ernst.

April 13, 2013: Alberta Government appoints Encana/Cenovus/Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers multi-year Executive Gerard Protti to Chair the new Alberta Energy Regulator (100% funded by industry and now controls all of Alberta’s fresh water), previously the ERCB.

September 19, 2013: Justice Wittmann’s ruling on the hearing he did not hear, gives the ERCB (now AER) complete immunity, even for violating Ernst’s Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms; rules there is no evidence that Ernst is a terrorist.

September 15, 2014: The Alberta Court of Appeal denied Ernst’s appeal, ruling [Ruling later removed from Alberta Courts. Click here for the ruling] that the AER cannot be sued by citizens – not even if it breaches (Harper’s despised) Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

April 30, 2015: The Supreme Court of Canada agrees to hear the Ernst vs AER appeal.

July 27, 2015: Deadline for all Attorney Generals, provincially and federally, to give notice of intent to intervene in the Ernst hearing at the Supreme Court. Will Harper intervene? Will the new NDP Alberta government? ]