Methane emissions from the 2015 Aliso Canyon blowout in Los Angeles, CA by S. Conley, G. Franco, I. Faloona, D. R. Blake, J. Peischl, and T. B. Ryerson, February 25, 2016, Science

DOI: 10.1126/science.aaf2348

Abstract

Single-point failures of the natural gas infrastructure can hamper deliberate methane emission control strategies designed to mitigate climate change. The 23 October 2015 blowout of a well connected to the Aliso Canyon underground storage facility in California resulted in a massive release of natural gas. Analysis of methane (CH4) and ethane (C2H6) data from dozens of plume transects from 13 research aircraft flights between 7 Nov 2015 and 13 Feb 2016 shows atmospheric leak rates of up to 60 metric tonnes of CH4 and 4.5 metric tonnes of C2H6 per hour. At its peak this blowout effectively doubled the CH4 emission rate of the entire Los Angeles Basin, and in total released 97,100 metric tonnes of methane to the atmosphere. [Emphasis added]

SoCalGas fights against reporting amount of massive Porter Ranch gas leak by Mike Reicher, February 21, 2016, Los Angeles Daily News

The Southern California Gas Co. is fighting potential state rules that would require it to report how much methane it lost in the catastrophic leak that spewed greenhouse gases into the air above Porter Ranch.

In a filing with the state Public Utilities Commission last week, an attorney representing the Gas Co. and other utilities argued regulators were stepping outside their bounds in considering the rules and that utilities don’t know how to measure the amount of methane escaping from major leaks.

The state Air Resources Board estimated the broken well at the Gas Co.’s Aliso Canyon storage facility leaked 94,000 metric tons of methane, the same climate impact as roughly 1.7 million passenger cars on the road for a year.

Nonetheless, an attorney representing SoCalGas and other utilities wrote in the filing: “In the event of catastrophic pipeline failures, the joint utilities are not aware of any established methodology that could be used to determine the release of methane,” referring to the volume of gas emitted. [Should those utilities be allowed to store methane then?]

The filing comes after SoCalGas had been paying for a pilot to fly over the Aliso Canyon natural gas storage facility to measure methane released from the once-leaking well. And the company’s chief executive, Dennis Arriola, has repeatedly said the company would, in fact, determine how much gas leaked from the well and would somehow make the environment whole.

“I want to assure the public that we intend to mitigate environmental impacts from the actual natural gas released from the leak,” he said in an earlier statement on the company’s website.

The filing rankled environmentalists, who are watching skeptically as the company plans to compensate for the Aliso Canyon leak’s environmental harm. [Or, get out of legal liability?]

“It’s shameful they would try in public to take a leading position and then at the same time file papers in an obscure filing that totally backtracks on that,” said Tim O’Connor, director of the California oil and gas program at the Environmental Defense Fund.

STATE LAW AT ISSUE

… Pipelines and storage facilities leak regularly, so state lawmakers passed a law in 2014, SB 1371, designed to better track leaks and reduce emissions. While the companies aren’t penalized for leaks, a spike from the Aliso Canyon leak would certainly make SoCalGas look bad. Each May, utilities provide their leak tallies for the previous year.

An administrative law judge in October asked for comments on the format of this year’s reporting form. After the Aliso Canyon leak was discovered, the Environmental Defense Fund and Utility Workers Union of America recommended an additional line-item: “catastrophic failures such as pipeline or storage well failures.” Today, utilities don’t have to report such emissions. The judge included the suggestion in the proposed changes.

SoCalGas, San Diego Gas & Electric Co. and Southwest Gas Corp. filed a joint response Wednesday, asserting that the law was meant to reduce emissions from common equipment malfunctions, not disastrous leaks covered by existing “safety” or “integrity” management plans. In the case of natural gas wells, integrity usually refers to detecting and preventing underground corrosion.

“Adding a specific focus on isolated events stands to distract from that intent, and could lead to reporting of emissions that are outside of the scope of SB 1371,” wrote Melissa Hovsepian, an attorney representing the utilities.

O’Connor from the Environmental Defense Fund disputes that. The bill was intended to “minimize leaks,” he points out, and a leak is defined by federal regulators as “an unintentional escape of gas from the pipeline.” Generally, the utilities are trying to limit the effects of the SB 1371, O’Connor said, by arguing their current business practices governed by existing regulations (such as managing safety), would conflict with SB 1371. Reporting and preventing catastophic leaks might overlap with the intent of other laws, O’Connor said, but they wouldn’t clash.

According to the bill’s text, SB 1371 is meant to advance the goals of “natural gas pipeline safety and integrity; and reducing emissions of greenhouse gases.”

A SoCalGas spokeswoman did not make someone available for an interview Saturday afternoon and, in a written response, did not address the assertions in the regulatory filing. Anne Silva instead said the company still plans to make up for the leak’s environmental impact. [Emphasis added]

What caused nosebleeds in Porter Ranch? New questions emerge by Mike Reicher and Susan Abram, Ingrid Lobet from inewssource contributed, February 8, 2016, Los Angeles Daily News

For weeks after the gas leak began near Porter Ranch, Los Angeles County health officials kept assuring residents that their complaints of headaches, dizziness and nosebleeds were similar to what had happened in a small town in Alabama.

There, residents from unincorporated Eight Mile in Mobile County complained of a rotten egg smell, of the way the foul odor messed with their breathing and their stomachs. Lightning had struck a storage tank holding thousands of tons of mercaptan, a pungent chemical added to natural gas so it can be detected by smell. The odorant seeped into a beaver pond in Eight Mile and years later residents complained of headaches and dizziness.

But the people of Eight Mile never reported nosebleeds. In Porter Ranch, however, a third of 600 households complained of bloody noses, according to the results of a Los Angeles county public health survey released on Monday. What’s more, not all households that reported nosebleeds could smell the mercaptans, according to the report.

Health officials are now raising questions about what caused the bleeding, which they acknowledge is inconsistent with the very few health studies that exist on mercaptans. A better-documented and more hazardous compound found in natural gas — hydrogen sulfide — could explain some of the symptoms, independent experts say. And emerging science shows this dangerous chemical compound could be more abundant than originally thought.

“The high prevalence of reported nosebleeds and low prevalence of reported odor are noteworthy, however, and somewhat inconsistent with expectations,” according to the public health report, which includes results of expanded air monitoring in Porter Ranch. “Additional testing may be warranted to investigate these observations.”

Dr. Mary McIntyre, epidemiologist for the Alabama Department of Public Health, went with a team of experts to Eight Mile in 2012 to report on health complaints from the mercaptan spill.

“No information was provided or indicated by the people who were part of the survey that they were having problems with nosebleeds,” she said.

Of the 204 people in Alabama who responded to the survey, most complained of sore throats, nasal congestion and difficulty breathing. McIntyre said what happened in Alabama should not be compared to Porter Ranch because one was a pure mercaptan spill, the other was a natural gas leak.

“I do not think it’s apples to apples,” she said.

QUESTIONS RAISED

While health officials and Southern California Gas Co. executives have maintained that Porter Ranch residents’ symptoms were the effects of smelling the odorants, some experts are raising other possibilities.

These are “classic symptoms” of exposure to hydrogen sulfide, a well-documented toxic compound, said Michael Jerrett, professor and chairman of the UCLA Department of Environmental Health Sciences.

More serious effects of hydrogen sulfide range from fluid in the lungs to respiratory distress and irregular heartbeat.

Angelo Bellomo, deputy director for health protection at the Los Angeles County Dept. of Public Health, said the nosebleeds could be attributed to nasal irritation from sulfur compounds in general, including hydrogen sulfide and mercaptans.

Hydrogen sulfide, though, has been detected at mostly low levels and very infrequently in Porter Ranch, Gas Co. representatives and air quality officials point out.

One Gas Co. executive said it is highly unlikely that people are smelling hydrogen sulfide.

“Hydrogen sulfide can occur in natural gas, but it is at very low levels and intermittent,” said Gillian Wright, vice president of customer services for SoCalGas, in an earlier interview.

EMERGING SCIENCE

But it may be more abundant in the gas than originally thought, some emerging science indicates. Researchers in Australia discovered that methyl mercaptan, one of the odorants found in Aliso Canyon gas, may convert to hydrogen sulfide under the right circumstances, said Mel Suffet, professor in the UCLA Department of Environmental Health Sciences. While the study is unpublished, Suffet reviewed it as a member of a peer panel.

The anaerobic underground conditions in a former oil field such as Aliso Canyon would be a potential environment for the mercaptan conversion, Suffet said, “that could be one of the causes of hydrogen sulfide.”

While the Gas Co. doesn’t add methyl mercaptan (it uses two other odorants), its suppliers or producers sometimes do, according to spokeswoman Kristine Lloyd. In one January air sample, the Gas Co. measured all three odorants, she said.

Utilities choose mercaptans because they can typically be smelled at lower concentrations than hydrogen sulfide, said Wright, the Gas Co. executive. But the public health survey found only 17 percent of Porter Ranch households reported smelling the odor — with 32 percent reported nosebleeds — so county health officials were puzzled.

Bellamo, from the health department, and state officials from the state Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, weren’t aware of the possible conversion between the two compounds.

FOUND AT LOW LEVELS

In a summary of the air quality findings online, a Gas Co. consultant acknowledged that hydrogen sulfide in the neighborhood exceeded the state standard once, according to air tests, but said the compound was otherwise “below levels of health concern.”

The state standard for health risks from hydrogen sulfide is 30 parts per billion, averaged over one hour of exposure. Initially, the company indicated that results were below the standard, but later made a correction.

While Porter Ranch may be mostly below the state threshold, “it’s entirely possible that levels below that could be causing the symptoms reported,” Jerrett said.

The Gas Co. detected hydrogen sulfide at least 11 times from Oct. 30 through Jan. 13, according to tests compiled by UCLA researchers. The concentration ranged from 3.8 parts per billion to 29.1 parts per billion, except for one instance when it reached 183 parts per billion. In the typical American city’s air, hydrogen sulfide ranges from 0.1 to 0.3 parts per billion, according to the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

The Gas Co. has tried to distance itself from the findings. Harmful sulfur compounds “were not detected in the gas leaking from the well,” Dr. Mary McDaniel of Intrinsik Environmental Sciences wrote in the online summary of health effects. “Therefore, it is unlikely that the detections in air of these sulfur compounds related to the gas leak.”

UNKNOWN EFFECTS

With this logic, Jerrett believes Gas Co. officials have discounted the possibility of hydrogen sulfide exposure. It may not have been consistently measured, he and other experts say, for a variety of reasons.

The gas was likely “pulsing” from underground, Jerrett said, and emitting hydrogen sulfide intermittently, in waves. So tests taken by the well, at a particular moment in time, might not have registered the compound.

“It’s a very volatile, rapidly moving plume,” Jerrett added.

While the hydrogen sulfide could have come from other sources — such as natural emissions from oil and gas operations — it is unlikely at those concentrations, Jerrett said.

Also, the compound breaks down quickly, sometimes before a laboratory has the chance to detect it, said Don Gamiles of Argos Scientific, an independent air testing company that recently started monitoring in Porter Ranch.

A minority of the tests conducted by SoCalGas had very high thresholds for detection — some at 50 parts per billion, much higher than levels considered safe by state regulators. In other words, the compound might not have shown up on those results, even if it was at dangerous levels.

This testing method was “of limited use,” said Sam Atwood, spokesman for the South Coast Air Quality Management District.

For several weeks his agency has been monitoring for hydrogen sulfide in Porter Ranch, using lower detection levels. Officials haven’t detected it above 3 parts per billion, he said, and on many dates it has registered around zero.

But the district wasn’t testing for hydrogen sulfide in the early weeks of the leak, when gas was escaping at a higher rate. If residents were exposed to hydrogen sulfide for weeks or months, the possible health effects are uncertain. Nobody has researched the medium or long-term exposure to humans at low levels of hydrogen sulfide, according to the World Health Organization.

“There just isn’t a lot of evidence where we know what the long-term implications are for people’s health,” Jerrett said. [Emphasis added]

Massive California gas leak unlikely to be repeated in Ontario, ministry says by Paul Morden, January 17, 2016, Sarnia Observer

A leak of natural gas stored underground, on the scale of one that has forced thousands of southern California residents from their homes for months, is unlikely to happen in Lambton County, officials say.

[How do they know if Ministry of Natural Resources doesn’t have records or locations for 23,000 – 30,000 oil and gas wells drilled in Ontario, and can’t or won’t define “high volume hydraulic fracturing?”]

The ground in Sarnia and Lambton County is home to a significant number of salt caverns and depleted wells used by the chemical and energy industry to store natural gas, other hydrocarbons and liquified petrochemicals.

This storage is a largely unseen but significant resource for industry in Sarnia-Lambton, and other regions.

… In Ontario, storage wells are regulated by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry.

“Due to Ontario’s much more stringent regulatory requirements and lower pressures and volumes for storage, an event similar to that in California is extremely unlikely,” [Not reassuring when that’s what they all say, and no one is monitoring or studying the cumulative impacts to storage facilities, caprock, etc from repeat perforating and fracing, earthquakes caused by waste injection and or fracing, casing corrosion, leaks etc ] ministry spokesperson Jolanta Kowalski said in an e-mail.

The ministry regulates storage wells through a national standard setting out requirements for the design, operation, maintenance, safety, monitoring and testing, Kowalski said.

As well as extensive underground storage in Sarnia-Lambton’s Chemical Valley, Dawn-Euphemia Township is home to a large natural gas storage and trading hub owned by Union Gas.

“Not all storage is the same,” said Andrea Stass, a spokesperson for Union Gas.

The underground storage pools Union Gas operates in Dawn-Euphemia are much smaller than those in California, she said.

“They’re shallower, and they operate at a much lower pressure,” Stass said.

“Those things combined, significantly reduce the risk of a similar incident.”

The Union Gas wells in Dawn-Euphemia operate at an average pressure of approximately 1,1,00 to 1,500 pounds per square inch, about half of what’s used at the California wells, Stass said. [What when/if greed induces increased pressure and risks?]

The Union Gas storage wells pipes are encased in four layers of steel and concrete, plus an electrical current runs on the outside of the outermost casing to deter corrosion, she said.

“We have a very rigorous well maintenance program, and that includes regular inspection of all our storage wells,” Stass said.

“If we detect any metal loss or corrosion, we fix that before it becomes an issue.” [That’s what they all say too. How often do energy companies tell the truth?]

Union Gas began developing the Dawn Hub 70 years ago and now has 23 storage pools there.

“We’ve never had an incident,” Stass said.

The Dawn hub is a “significant asset” connected to major supply basins and pipeline systems across North America.

It supports Ontario’s natural gas supply, and is also a market hub where companies buy, sell and trade natural gas, she said.

Dean Edwardson, general manager of the Sarnia-Lambton Environment Association, an organization made up of 20 industrial manufacturers, said underground storage wells are monitored, regulated and maintained.

“The likely of something coming up from those caverns is probably a little more remote than a natural phenomenon,” he said.

In June 2015, Lambton Shores officials declared a localized state of emergency after geysers of natural gas blew out of a creek at the Indian Hills Golf Course.

It was determined to a naturally occurring event, since there were no pipelines in the area, and no other man-made sources for the gas found.

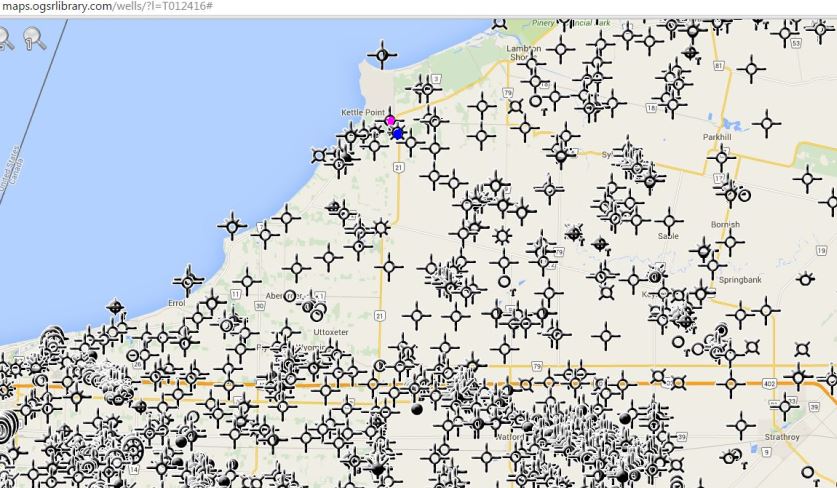

[Honesty Check:

Pink is abandoned energy well near the Indian Hills geysers

Blue is an industry gas well (black are other energy wells)

Was the industry gas well (blue dot) near the Indian Hills gas geysers frac’d or refrac’d, or others nearby frac’d/refrac’d?

End Honesty Check ]

The website of the Ontario Petroleum Institute notes there are 73 active storage caverns in Ontario, using 124 wells with a total storage capacity of 3.5 million cubic metres.

“This kind of infrastructure is obviously an asset, both in terms of product storage and raw material storage,” Edwardson said.

Pembina operates a facility near Corunna on a 1,000-acre underground storage site originally owned by Dow Chemical.

In an application to the province in early 2015, Pembina said it wanted to expand the facility’s storage capacity by converting 11 currently unused salt caverns to hydrocarbon storage within the next 15 years. [To store all that frac’d Ontario “natural” gas the Ontario Government doesn’t want citizens to know about?]

That would increase on-site storage capacity at the facility from 10 caverns to 21, and 826,000 cubic metres to more than 2.2 million cubic metres, the company’s application says. [Emphasis added]

Unlikely in Ontario?

2015 Indian Hills Ontario Gas Eruptions 27 seconds by Jamie Reitknecht

[Refer also to: