Emails just in from Ireland as I finished this post:

1.

That’s unrealistic guilt Jessica.We build our campaign on your shoulders. You saved us when you filled the Rainbow that night. There’s bans on fracking all over the place because of you. Remember how hard it was to get you into Dail. They thought you were a terrorist. I remember Senator Joe O Reilly apologising to me afterwards and saying that your were welcome back any time. Last week we finally got a formal policy statement stating that Ireland will not import fracked gas.

That campaign started when you were back celebrating our ban. We couldn’t stop campaigning because you never did.

That policy statement included a statement saying that Ireland will work with international partners to promote the phasing out of fracking at the international level.

Now we’re going global.

We’re one decision away from the Irish government raising a resolution asking the U.N. to call for a global ban on fracking.

You have a way of getting people to take action they otherwise probably wouldn’t.

Don’t feel bad about losing a battle. All of us together are going to change everything.

That weight your feeling isn’t failure Jessica. It’s the weight of all of us standing on your shoulders.

You can now let that case go. It’s done it’s job. Focus on your success.

We look forward to the day we can all meet again. Regards

On Mon 24 May 2021, 18:12 Jessica Ernst wrote:

Thank you… your words are so kind, and ease my grief.

I feel I failed the world. It’s an awful feeling.

all my best to you… love jessica

2.

Today you were very much in our hearts at the launch of the report on Human Rights and fracking from Galway and Eddie mentioned you as being so important to our campaign. We are petitioning the Irish Govt to call for a Global ban on fracking. … Enjoy the rain!! Looking forward to walking in Glenfanre Woods with you soon again. Lots of love,

Fracking not compatible with human rights law, says Irish study, A new report from NUIG’s Centre for Human Rights calls on the State to use its weight at the UN to push for a global ban on fracking by thejournal.ie May 24, 2021

The extraction of gas through fracking goes against international human rights law, according to a new study by Irish researchers.

Fracking is a process for extracting gas by drilling into shale rock and injecting pressurised water, sand and various chemicals to force out the gas.

The report, prepared by human rights law students at NUI Galway’s Centre for Human Rights, argues that fracking must be banned worldwide as the dangers posed by the extractive process cannot be offset by merely regulating the process.

The NUIG report points to a significant body of scientific evidence that outlines the danger posed by the industry to health, water, air, farmland soils and the general economic vitality of communities where the industry is established.

In the US, for example, the industry is linked to various health impacts, while a recent study from Cornell University found that rising levels of methane – a potent greenhouse gas – is linked to emissions from the fracking industry.

In Ireland, a 2017 study from the Environmental Protection Agency found that the practice has the potential to damage human and environmental health.

Therefore, the NUIG report argues, fracking is incompatible with countries’ legal obligations to protect, respect and fulfil basic human rights including the right to life, health, water and a healthy environment.

Calls for strong voice at UN

As the Republic of Ireland has become one of the first countries in the world to ban fracking, the NUIG law students are calling on the State to sponsor a UN General Assembly resolution for a global ban on fracking. The students have drafted the wording for a resolution and sent it to the Minister for Foreign Affairs Simon Coveney to consider.

Bridget Geoghegan, one of the report’s authors, said that the proposed resolution outlines that fracking is an “inherently harmful extraction process that has global impacts no matter where it is conducted”.

“No amount of regulation can adequately address all the problems that fracking causes,” she said, adding that the proposed resolution is in line with principles outlined in the State’s new policy statement on fracked gas imports.

Last week, the Minister for the Environment Eamon Ryan released a policy statement outlining a moratorium on the development of fracked gas importation pending the findings of a State review on security of energy supplies.

Introducing a ban on the importation of fracked gas was one of the climate policies in the Programme for Government following pressure from Green Party members and grassroots environmental groups, Ryan said.

The policy statement sets out the Government’s commitment to work with international partners to “promote the phasing out of fracking at an international level within the wider context of the phasing out of fossil fuel extraction”.

The NUIG report was officially launched at an event this evening featuring speakers from affected communities in the US and Namibia, as well as guests from Fermanagh, a county with large deposits of shale rock.

Fracking is yet to be banned in Northern Ireland and there are currently live licence applications for exploratory drilling in the Lough Allen area.

The Department for the Economy recently put out a tender for a research project to examine the “economic, societal and environmental impacts of future onshore petroleum exploration and production”

The study includes an examination of unconventional oil and gas (UOG) production, under which the practice of fracking would fall.

The study was commissioned soon after a cross-party motion unanimously passed in the Northern Ireland Executive in October 2020 that called for legislation to be introduced to ban any new licensing for oil and gas exploration.

International Human Rights Impacts of Fracking Report by Rowan Hickie and Bridget Geoghegan, LLM candidates, May 2021, The Irish Centre for Human Rights, NUI Galway

Notes

The authors of this report are LLM candidates in International Human Rights Law at the Irish Centre for Human Rights (ICHR), NUI Galway. Rowan Hickie holds a Bachelor of Arts Honors degree and Juris Doctor degree from the University of Alberta, Canada. Bridget Geoghegan holds a Bachelor of Civil Law degree from NUI Galway.

This report has been prepared in collaboration with Safety Before LNG, Love Leitrim and

Letterbreen and Mullaghdun Partnership (LAMP) as part of the work of the Human Rights

Law Clinic at the Irish Centre for Human Rights, NUI Galway.

This report is a revised version of a report prepared for LAMP, examining the human rights impacts of fracking and the obligations which the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland hold in regard to fracking. This report has been revised to be more widely applicable to all States Parties to the human rights treaties discussed.

The ICHR at the School of Law, National University of Ireland Galway, is Ireland’s principal academic human rights institute. The ICHR undertakes human rights teaching, research, publications, and training, and contributes to human rights policy development nationally and internationally. The Human Rights Law Clinic at the ICHR was launched in 2019 and is directed by Dr Maeve O’ Rourke. The Clinic introduces students to ‘movement lawyering’ and enables students to contribute their skills to community-based movements for social change. In preparing this report, the authors received assistance and feedback from Dr. Maeve O’Rourke, Pearce Clancy, Johnny McElligott, Eddie Mitchell, and Dianne Little. We are thankful for the expertise and insightful feedback shared with us for the purpose of writing this report.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of this report and all opinions and any errors are their own.

Executive Summary

Climate change poses a major threat to our planet. This reality has been recognized by the

United Nations and broader international legal community.1

Unconventional oil and gas extraction, including processes such as hydraulic fracturing, pose a significant threat to human rights through both their contribution to climate change and their procedures’ impacts on surrounding communities. Academics, researchers and medical professionals have stressed that ‘the evidence clearly demonstrates that the processes of fracking contribute substantially to anthropogenic harm, including climate change and global warming, and involve massive violations of a range of substantive and procedural human rights and the rights of nature.’2 The Concerned Health Professionals of New York and Physicians for Social Responsibility in their 7th Edition of the Compendium of Scientific, Medical and Media Findings Demonstrating Risks and Harms of Fracking (Unconventional Gas and Oil Extraction) (hereinafter the ‘Compendium’) conclude that ‘a significant body of evidence has emerged to demonstrate that these activities are dangerous in ways that cannot be mitigated through regulation.’3

Human rights impacted by fracking and its contribution to climate change include, but are not necessarily limited to, the right to life, the right to health, the right to water, the right to food, the right to housing, the right to access to information, the right to public participation, the right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, with violations of these rights having disproportionate impacts on marginalized and vulnerable communities and groups.

These human rights are contained in numerous international and regional human rights

instruments and treaties, to which many States are party, including Ireland.4 These international human rights instruments include:

• The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR);5

• The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR);6

• The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC);7

• The United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination

against Women (CEDAW);8

• The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD);9

and

• The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

(ICERD).10

In addition to the treaties mentioned above, the European Convention on Human Rights

(ECHR)11 similarly enumerates human rights obligations, binding on a number of all Council of Europe member states.

United Nations treaty bodies, special rapporteurs and civil society organizations have

recognized and noted the negative impacts that fracking and climate change pose to the human rights contained within these instruments. Once a State has ratified the above mentioned

international and regional human rights instruments, it is bound by its obligations thereunder to respect, protect and ensure these international human rights are met.

As reflected in the content of this report, it is difficult to see how a State can propose and utilize fracking operations without breaching its international and regional human rights obligations.

As a result, it is recommended that States:

• Refrain from implementing fracking practices, and in accordance with the CEDAW

Committee’s 2019 recommendation to the United Kingdom, introduce a

comprehensive and complete ban on fracking;12

• Prohibit the expansion of polluting and environmentally destructive types of fossil fuel

extraction, including oil and gas produced from fracking, as per the recommendation of

the Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment;13 and

• Commit to attaining and upholding the highest standards of the rights to life, health,

water and food, and ensure that no State or private initiatives disproportionately impact

these rights.

… As will be demonstrated, unconventional oil and gas exploration (hereinafter referred to as ‘fracking’) impacts a wide array of human rights, including the right to life, health, water, food, housing, access to information, public participation, a safe, clean and healthy environment, with human rights violations often disproportionately impacting marginalized individuals and communities such as women, children and persons living in poverty.

States, in making a determination of whether to implement fracking, should be made aware of the impacts that the exploration for, exploitation of and use of fossil fuels will have not only on their environments, but also on their people and their obligations under international agreements and treaties to which they are party. Further, as the impacts of climate change and fracking and the resulting pollution do not respect State boundaries, States must be aware of the implications their fracking practices may have on not only their citizens, but also on citizens of other States. In particular, contamination of water, air pollution and the emission of greenhouse gases can contribute to and pose a risk to human rights in neighbouring States and on the environment globally. …

1.2 What are the Risks of Fracking?

Fracking poses severe risks to the environment and to human health and wellbeing through both the physical procedures involved in and associated with the act of fracking, but also in the carbon emissions that result from the fossil fuels that the fracking process creates.

As noted by the Concerned Health Professionals of New York and Physicians for Social

Responsibility in their 7th Edition of the Compendium of Scientific, Medical and Media

Findings Demonstrating Risks and Harms of Fracking (Unconventional Gas and Oil

Extraction)22 (hereinafter the ‘Compendium’), fracking can result in devastating environmental impacts such as water contamination, air pollution, earthquakes and radioactive contamination.23

The storage of contaminated waste waters and the potential for these waters to leak and

contaminate ground water are one of the environmental issues associated with fracking.24 Air pollution surrounding fracking infrastructure in the United States was found to have high levels of toxic pollutants, including ‘carcinogen benzene and the chemical precursors of ground-level ozone (smog)’, which cause severe environmental damage and risks to human health.25 In addition to the environmental damage and risks that fracking poses, there are also severe risks to human health and well-being

… In addition to the public health impacts of fracking, the Compendium further finds that fracking itself is a ‘dangerous process with innate engineering problems that include uncontrolled and unpredictable fracturing, induced earthquakes, and well casing failures that worsen with age and lead to water contamination and fugitive emissions.’ … From fracking’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, to the immediate impacts fracking has on the surrounding community, fracking poses severe risks to the human rights of persons immediately surrounding fracking operations and around the world.

1.3 What are International Human Rights?

There are several international treaties that are relevant in assessing the international human rights impacts of fracking. International environmental treaties such as the Paris Agreement are also of relevance to the discussion of States’ obligations to combat climate change and secure human rights. As noted by the Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, David Boyd: ‘Human rights obligations are reinforced by international environmental law, as States are obliged to ensure that polluting activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause serious harm to the environment or peoples of other States or to areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.’30 …

2. International Human Rights Obligations

… Fracking poses a threat to human rights through both its contribution to climate change and its own direct impacts on surrounding communities. As the Compendium notes, ‘the evidence clearly demonstrates that the processes of fracking contribute substantially to anthropogenic harm, including climate change and global warming, and involve massive violations of a range of substantive and procedural human rights and the rights of nature.’39

2.1 Right to Life

The right to life is one of the most widely recognized rights in international human rights law.40 The right to life protects against State action or inaction which poses risk to the life of persons. As the Human Rights Committee notes, State obligations in relation to the right to life include protecting against ‘reasonably foreseeable threats and life-threatening situations that can result in loss of life.’41 States may violate the right to life by exposing individuals to a real risk of the deprivation of life, even if the risk does not result in an actual loss of life.42 States have an obligation to take appropriate measures to ‘address the general conditions in society that may give rise to direct threats to life or prevent individuals from enjoying their right to life with dignity.’43 Thus, States may violate the right to life through not only deprivation of life, but also the deprivation of the right to life with dignity. ![]() It’s humiliating to live without adequate safe water. Bathing and house cleaning is rationed. I no longer allow visitors because my frac’d home is no longer clean, neither am I. Social events are usually declined because they require bathing, which requires hauling water which I often do not have the energy for (it’s at minimum, a two hour process; sometimes hours longer if there is a long line up – frac trucks take forever to fill).

It’s humiliating to live without adequate safe water. Bathing and house cleaning is rationed. I no longer allow visitors because my frac’d home is no longer clean, neither am I. Social events are usually declined because they require bathing, which requires hauling water which I often do not have the energy for (it’s at minimum, a two hour process; sometimes hours longer if there is a long line up – frac trucks take forever to fill).

Think of all that potable water we the people pay for (frac’ers usually get it for free), intentionally contaminated with toxic chemicals, then injected, much of it lost to life on earth forever.![]()

…

2.1.2 The impact of fracking on the right to life

As will be discussed in greater detail below, fracking poses significant public health risks to

the communities and individuals surrounding the fracking operations, but also a significant risk through its contribution to the larger issue of climate change. The end product of fracking, natural gas, is not a climate-friendly fuel.62 In addition to the end product of natural gas, the process of fracking results in large amounts of methane emissions escaping during the fracking process. Methane is ‘a powerful greenhouse gas that traps 86 times more heat than carbon dioxide over a 20-year time frame.’63 Methane released during the fracking process is largely referred to as fugitive emissions, and can occur during the drilling, storage and ancillary processes.64

Climate change, as noted by various human rights and international bodies, poses a grave risk to the planet, and States, pursuant to their obligations to ensure the right to life, must take action to combat the degradation of the environment in order to protect the right to life and the right to life with dignity.

2.2 Right to Health

The right to health has been described as a fundamental human right, ‘indispensable for the exercise of other human rights.’65 Pursuant to the right to health, everyone is ‘entitled to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health conducive to living a life in dignity.’66 …

2.2.2 The impact of fracking on the right to health

Fracking poses a risk to the right to health on two fronts. First, in its contribution to climate change, and second in regard to the impacts fracking has on the immediate and surrounding community. …

In 2019, the Permanent People’s Tribunal (PPT), a tribunal which examines serious and

systemic violations of human rights committed by States or private groups or organizations, issued an advisory opinion on ‘Human Rights, Fracking and Climate Change’. After hearing from various civil society organizations on the impact of fracking on human rights, the PPT issued an advisory opinion, ultimately calling for a global ban on fracking.88 The Tribunal found that the evidence provided made clear that the fracking industry has violated both substantive and procedural human rights law, where the techniques utilized in fracking breaching international human rights obligations ‘especially the right to health, by attacking all the components of natural ecosystems that can reach their destruction and therefore result in an ecocide; and threaten the enjoyment of all human rights of the present and future generations through its direct contribution to climate change.’ 89 As the impacts are felt by the ‘populations closest to the places of exploitation, they also often violate procedural human rights protected by international law, especially the rights of access to information and participation in decision-making; and also, frequently, they violate the environmental impact assessment obligations, and rights of human rights defenders.’90

Accordingly, the Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment recommended that developed States may demonstrate leadership in the area of human rights and the environment through ‘Prohibiting the expansion of the most polluting and environmentally destructive types of fossil fuel extraction, including oil and gas produced from hydraulic fracturing (fracking), oil sands, the Arctic or ultra-deepwater.’91 …

2.3 Right to Water

Water is essential for communities and ecosystems. It supports not only life systems, but also cultural and economic activities and is accordingly essential for the enjoyment of other human rights. The right to water is recognized in CEDAW, 93 CRC, 94 and CRPD.95 In 20120 the UN UN General Assembly affirmed in resolution 64/292 that ‘safe and clean drinking water and sanitation is a human right, essential for the full enjoyment of life and all other human rights’.96 The right to water has been further affirmed as constituting a human right by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in General Comment No. 15, in which the right to water was described as ‘fundamental for life and health’97 and ‘a prerequisite for the realization of other human rights’.98 Further, the Committee emphasized that the right to water entitles everyone to ‘sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic uses.’99

![]() Frac’d Water Interlude

Frac’d Water Interlude

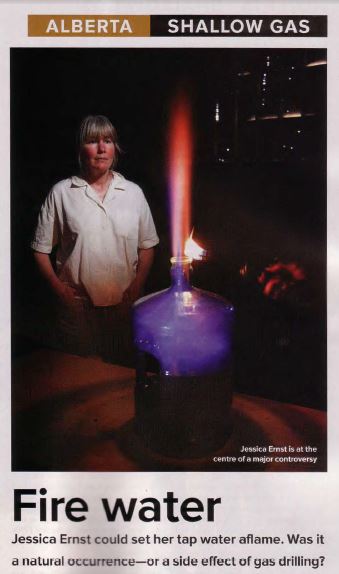

My water in 2006, photo by Colin Smith. At the time, industry, regulators and even NGOs claimed frac’ing was perfectly safe, good for the environment, and would never contaminate water. Fast forward a few years and industry not only admits frac’ing (coalseam gas needs more frac’ing than from other formations) contaminates drinking water aquifers, it admits so in huge full page ad in the Calgary Herald!

2011: Australian Petroleum Association: Coal seam damage to water inevitable

The coal seam gas industry has conceded that extraction will inevitably contaminate aquifers. “Drilling will, to varying degrees, impact on adjoining aquifers,” said the spokesman, Ross Dunn. “The intent of saying that is to make it clear that we have never shied away from the fact that there will be impacts on aquifers,” Mr Dunn said.

2014: Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers: Coal bed methane operations contaminate water resources from full page ad in The Calgary Herald

End frac’d water interlude![]()

2.3.1 The right to water recognised by international treaties and instruments

Access to safe and clean water directly impacts various human rights, as recognized by treaty bodies such as CESCR, in which the Committee recognizing the importance of access to water for the purposes of agriculture and the right to adequate food.100 The Committee has further linked the importance of water in relation to human dignity, life and health and in ensuring the sustainability of water supplies to ensure the right to water for future generations.101

The right to water does not merely require access to water, but also access to clean water. States must ensure that ‘natural water resources are protected from contamination by harmful substances’102 and that water must be ‘free from micro-organisms, chemical substances, and radiological hazards that constitute a threat to a person’s health.’103 Contaminated water poses severe risks to the lives and health of those dependent on it and has been noted to exacerbate existing poverty in communities. 104

States, in meeting their obligation to ensure the right to water, are required to take deliberate, concrete and targeted steps. Such steps may include (but are not limited to) the following:

• Prohibiting interference with the right to water through ‘unlawfully diminishing or

polluting water’;105

• Preventing third parties (such as corporations) from ‘interfering in any way with the enjoyment of the right to water’;106 ![]() Try telling that to Canadian authorities/water/energy regulators.

Try telling that to Canadian authorities/water/energy regulators.![]()

• Adopting strategies to ‘reduce depletion of water resources, through unsustainable

extraction’;107

• Reducing and eliminating pollution of watersheds by harmful chemicals;108 and

• Ensuring that proposed developments ‘do not interfere with access to adequate

water’.109

States must take all necessary measures to ‘safeguard persons within their jurisdiction from infringements of the right to water by third parties’. This includes enacting and enforcing legislation to ‘prevent the contamination and inequitable extraction of water.’ Failure to do so amounts to a violation of the State’s obligations. 110

Further, in order for States to comply with their international obligations regarding the right to water, States must refrain from interfering with the right of water in other countries.111 States must refrain from engaging in actions that interfere ‘directly or indirectly, with the enjoyment of the right to water in other countries.’112 States must ensure that activities undertaken within their own jurisdiction do not impact of the ability of another State to realize the right to water for persons within its jurisdiction.113

The UN Special Rapporteur on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation, has also remarked upon States’ obligations to protect and promote the right to water. The Special Rapporteur emphasized that States, in entering into agreements regarding trade and investment, must ensure such agreements do not ‘limit or hinder a country’s capacity to ensure the full realisation of the human rights to water and sanitation.’114 In order to meet their obligations, States must ensure close monitoring and regulation of the use and any contamination of water from industry.115 …

2.3.2 The impact of fracking on the right to water

Fracking is a water-intensive activity that poses a risk to water resources by compromising the uantity (accessibility and affordability) as well as the quality of water available to affected communities. In fracking, as with other extractive activities, water is a key area of concern given the detrimental impacts fracking can have on this essential resource.123

Water depletion is an issue where the availability of a sufficient and continuous water supply is undermined. Fracking is a water intensive activity that poses a risk to many already over-utilized water resources. The International Energy Agency estimates that each fracking well may need anywhere between a few thousand to 20,000 cubic meters of water (between 1 million and 5 million gallons).124 For example, in 2010, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimated that an annual 70 to 140 billion gallons of water were used to fracture just 35,000 wells in the United States.125 The Compendium notes that ‘In Arkansas, researchers found that water withdrawals for fracking operations deplete streams used for drinking water and recreation’126 and ‘the volume of water used for fracking U.S. oil wells has more than doubled since 2016’.127

The right to water is also impacted by contamination, with the fracking process presenting several ways in which water may be contaminated. The fracking fluid injected underground contains chemicals, many of which are toxic. The potential for fracking and other extractive processes to contaminate water sources and supplies has been heavily reported on by various UN Special Rapporteurs.

The Special Rapporteur on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation, noted that ‘Both wells and pits are very likely to have ecological impacts, including the pollution of groundwater aquifers and contamination of drinking water.128 In his 2012 report,129 the special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes examined the adverse effects of unsound management of hazardous substances in extractive industries. In examining fracking, the Special Rapporteur noted that the excess water from oil or gas production and drilling luids ‘constitute hazardous wastes’130 and that sometimes this excess water is disposed of by either reinjecting it back into the oil and gas reservoir, disposed of in waste ponds or ‘dumped directly into streams or oceans.’131

The water used in fracking procedures often contains toxic substances, which can end up being released into the surface water during the extraction, transport, storage and waste disposal stages of fracking.132 The storage of wastewater and other waste materials may also result in the contamination of water systems through spills, leaks or floods.133 The Special Rapporteur cautioned that such unintended releases of contaminated wastewater can be expected to increase due to an ‘anticipated increase in the frequency and intensity of storms in the future, due to climate change.’134

According to the Compendium ‘more than 1,000 chemicals that are confirmed ingredients in fracking fluid, an estimated 100 are known endocrine disruptors, acting as reproductive and developmental toxicants, and at least 48 are potentially carcinogenic.’135

Statistical analysis by Physicians, Scientists, and Engineers for Healthy Energy (PSE) of the scientific literature available from 2009 to 2015 demonstrates that 69 per cent of original research studies on water quality found potential for, or actual evidence of, fracking-associated water contamination.136 These chemicals can migrate into underground water supplies and active or abandoned wells, which may serve as conduits carrying fracking fluids from deep underground into aquifers near the surface.137 Leaks and spills of drilling fluids, whether of chemicals used in fracking, wastewater or other substances, provide a further route for contamination. The Compendium notes a ‘2020 survey of groundwater wells in Kern County, California found widespread contamination with wastewater chemicals, including salts, that had leached from both surface pits and underground injection wells.’138 It is also highted in the Compendium that ‘A 2017 study found that spills of fracking fluids and fracking wastewater are common, documenting 6,678 significant spills occurring over a period of nine years in four states alone.’139

…

3.2 Article 8: Right to respect for private and family life

Article 8 provides that ‘everyone has the right to respect for his private ![]() During the early years I lived frac’d after I began trying to warn people about the harms of frac’ing, all my official mail arrived opened – for years, notably mail from regulators, gov’t and the FOIP office; my home was broken into with nothing stolen, not even two piles of cash – I was on my way for a New York and Michigan speaking tour, with my attic hatch left open

During the early years I lived frac’d after I began trying to warn people about the harms of frac’ing, all my official mail arrived opened – for years, notably mail from regulators, gov’t and the FOIP office; my home was broken into with nothing stolen, not even two piles of cash – I was on my way for a New York and Michigan speaking tour, with my attic hatch left open![]() and family life, his home and his correspondence’.322 This right may not be interfered with ‘except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.’323 The Court has interpreted the right broadly to include both respect for the quality of family life as well as the enjoyment of the home as living space.324 Breaches of the right to the home as living space are not confined to interferences such as unauthorised entry, but may also result from intangible sources such as noise, emissions, smells or other similar forms of interference.325 Furthermore, the Court has tended to interpret the notions of private and family life and home as being closely interconnected, and, for example, in one case it referred to the notion of ‘private sphere’326 or in another case ‘living space’.327

and family life, his home and his correspondence’.322 This right may not be interfered with ‘except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.’323 The Court has interpreted the right broadly to include both respect for the quality of family life as well as the enjoyment of the home as living space.324 Breaches of the right to the home as living space are not confined to interferences such as unauthorised entry, but may also result from intangible sources such as noise, emissions, smells or other similar forms of interference.325 Furthermore, the Court has tended to interpret the notions of private and family life and home as being closely interconnected, and, for example, in one case it referred to the notion of ‘private sphere’326 or in another case ‘living space’.327

Environmental damage comes into play if such damage affects private and family life or the home. As is the case for Article 2 on the right to life, State obligations are not limited to

protection against interference by public authorities but include obligations to take positive steps to secure the right. Moreover, the obligation does not only apply to State activities causing environmental harm, but to activities of private parties as well.328 …

In light of the environmental and health impacts posed by fracking, academics have

emphasized that fracking operations, whether exploratory or extractive, should ‘be subject to detailed environmental impact assessment and health impact assessment procedures sensitive to the human rights implications of the proposed operation.’344 ![]() Investors and banks will kill frac’ing long before that ever happens in Caveman Canada.

Investors and banks will kill frac’ing long before that ever happens in Caveman Canada.![]()

… [Lots more to read in the report]

4. Conclusion & Recommendations

Fracking, through its emission of greenhouse gases and contribution to climate change and the immediate environmental, social and public health impacts it causes for surrounding communities, poses numerous threats to the enjoyment and exercise of human rights. As

underlined in this report, the human rights impacted include the right to life, the right to health, the right to water, the right to food, the right to housing, the right to access to information, the right to public participation, the right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, with violations of these rights having disproportionate impacts on marginalized and vulnerable communities and groups.

In light of the abundant evidence demonstrating how international and regional human rights are and will be infringed by fracking, it is difficult to see how a State can propose and utilize fracking operations without breaching its international and regional human rights obligations.

As a result, we recommend that States:

• Refrain from implementing fracking practices, and in accordance with the CEDAW Committee’s 2019 recommendation to the United Kingdom, introduce a comprehensive and complete ban on fracking;363

• Prohibit the expansion of polluting and environmentally destructive types of fossil fuel

extraction, including oil and gas produced from fracking, as per the recommendation of the Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment; 364 and

• Commit to attaining and upholding the highest standards of the rights to life, health,

water and food, and ensure that no State or private initiatives disproportionately impact

these or other collective and individual rights.

Refer also to:

2019: Contaminated Life: The true cost and human rights impacts of unconventional gas

2019: Overview of International Human Rights Court Recommending Worldwide Frac Ban