Have you been impacted by fracking? We want to hear from you. Fill out our fracking impact survey and we’ll be in touch.

Excellent photos, video and links to all parts (with many more visuals) at link:

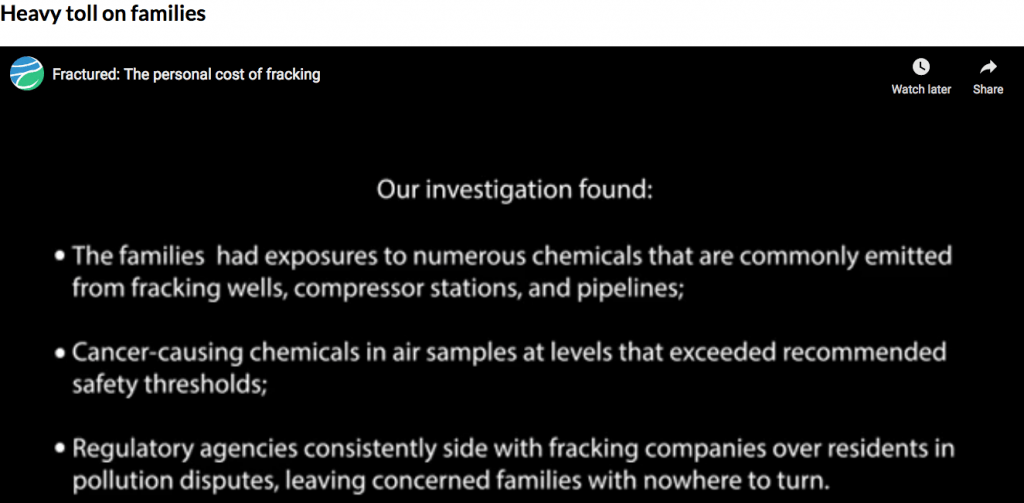

EHN.org scientific investigation finds western Pennsylvania families near fracking are exposed to harmful chemicals, and regulations fail to protect communities’ mental, physical, and social health by Environmental Health News (EHN) Staff, Mar 1, 2021.

It’s been 12 years since fracking reshaped the American energy landscape and much of the Pennsylvania countryside.

And despite years of damning studies and shocking headlines about the industry’s impact—primarily on the state’s poor and rural families—people that live amongst wellpads remain in the dark about what this proximity is doing to their health and the health of their families. A two-year investigation by EHN set out to close some of those gaps by measuring chemical exposures in residents’ air, water, and bodies.

In the summer of 2019, we collected air, water, and urine samples from five nonsmoking southwestern Pennsylvania households. All of the households included at least one child. Three households were in Washington County within two miles of numerous fracking wells, pipelines, and compressor stations. Two households were in Westmoreland County, at least five miles away from the nearest active fracking well.

Over a 9-week period we collected a total of 59 urine samples, 39 air samples, and 13 water samples. Scientists at the University of Missouri analyzed the samples using the best available technology to look for 40 of the chemicals most commonly found in emissions from fracking sites (based on other air and water monitoring studies).

Heavy toll on families

This was a small pilot study, so we aren’t able to draw any sweeping scientific conclusions from our findings. Instead, we hope our findings will provide a snapshot of environmental exposures in southwestern Pennsylvania families and help pave the way for additional research.

We found chemicals like benzene and butylcyclohexane in drinking water and air samples, and breakdown products for chemicals like ethylbenzene, styrene, and toluene in the bodies of children living near fracking wells at levels up to 91 times as high as the average American and substantially higher than levels seen in the average adult cigarette smoker.

The chemicals we found in the air and water—and inside of people’s bodies—are linked to a wide range of harmful health impacts, from skin and respiratory irritation to organ damage and increased cancer risk. But these stories are about more than a list of hard-to-pronounce chemicals. They’re about a single father on disability who fears these exposures are causing his son’s illness but can’t afford to move; a family that did move to escape a school surrounded by well pads, but found themselves living next to a new set of wells and still being exposed; and quiet rural lifestyles once defined by idyllic farms, rolling hills, and fresh air now overwhelmed by heavy truck traffic, heavy industry, and communities at odds over whether to protest that loss or try and cash in by leasing their mineral rights.

Fractured: Join us 1p ET on Monday, March 1 for a webinar with reporter Kristina Marusic

Far-reaching impacts

In the U.S., fracking has become a flashpoint in national debates about climate change and America’s energy future. In Pennsylvania, study after study after study has found that state lawmakers who support pro-fracking legislation have received vast amounts of money from the industry, while polls show that a majority of Pennsylvania residents oppose fracking. Meanwhile, financial analysts fret about the industry’s massive debt overhang and uncertain future, especially post-COVID-19.

While financial analysts, policymakers, and massive corporations squabble over the finer points of the fracking debate, families living amidst the wells day in and day out live in constant fear about what the industry might cost them—if they had another child, would they need to worry about birth defects? Are these exposures increasing their kids’ cancer risk? Would it be safer to move to a place far away from all of this, even if it would also mean being far from their extended families, friends, and communities? And even if they could move, how far would they have to go to feel safe?

EHN’s analysis also found unexpected exposures even in families that live further away from fracking wells in Westmoreland County, proving that in southwestern Pennsylvania, we really are all sharing the same airshed—and that exposure impacts from the oil and gas industry’s emissions likely extend far beyond just the people living right next door to well pads.

Environmental Health News is an award-winning nonpartisan organization dedicated to driving science into public discussion and policy. Read the 4-part series below, and listen to an interview with reporter Kristina Marusic about the science and investigation.

Our urine tests of five families in and near fracking country found biomarkers for hazardous fracking chemicals in children at levels far higher than those seen in the average American.

The pervasiveness of the industry in rural America leads to mental health issues including anxiety and depression among residents, and opens hard-to-heal rifts in communities.

Distrustful of doctors, fracking companies and state agencies, residents are getting few answers to their pleas for help.

Part 1: Harmful chemicals and unknowns haunt Pennsylvanians surrounded by fracking

… Scenery Hill is in Washington County, the most heavily fracked county in Pennsylvania, with about 1,584 wells in its 861 square miles….

August 19, 2019, was a typical day for Gunnar—he played drums, took the dog outside, and argued and joked with his siblings. But unbeknownst to him and his family, Gunnar had a number of harmful chemicals coursing through his body.

A urine sample taken from Gunnar that day contained 11 harmful industrial chemicals, including benzene, toluene, naphthalene, and lesser-known chemicals linked to a range of health effects including respiratory and gastrointestinal problems, skin and eye irritation, organ damage, reproductive harm, and increased cancer risk.

These chemicals are found in things like gasoline, pesticides, industrial solvents and glues, varnishes, paints, car exhaust, industrial emissions, and tobacco smoke. They’re also commonly detected in air emissions from fracking wells.

… Biomarkers (also referred to as breakdown products or metabolites) for harmful chemicals like ethylbenzene, styrene, and toluene in the bodies of southwestern Pennsylvanians at levels significantly higher than the average American. For example, we found a biomarker for toluene in a 9 year-old boy living near fracking wells at a level 91 times as high as the level seen in the average American ![]() Toluene damages the brain, notably in children. After Encana/Ovintiv illegally frac’d my community’s drinking water aquifers, with blessings and cover-up by our politicians and regulators, testing found toluene, naphthalene, benzene, chromium, barium, strontium, and more.

Toluene damages the brain, notably in children. After Encana/Ovintiv illegally frac’d my community’s drinking water aquifers, with blessings and cover-up by our politicians and regulators, testing found toluene, naphthalene, benzene, chromium, barium, strontium, and more.![]()

Families that live closer to fracking wells had higher levels of chemicals like 1,2,3-trimethylbenzene, 2-heptanone, and naphthalene in their urine than families that live further away. Exposure to these compounds is linked to skin, eye, and respiratory issues, gastrointestinal illness, liver problems, neurological issues, immune system and kidney damage, developmental issues, hormone disruption, and increased cancer risk. …

A few years ago, when drilling began simultaneously at three of the fracking well pads within a few miles of the Bower-Bjornson home, Gunnar frequently got nosebleeds that lasted up to 20 minutes and drained all the color from his face. Sometimes he’d cough up blood clots afterwards. ![]() I suffered the same, and was often woken up at night by soaking my pillow with a nose bleed. The coughing of the clots afterwards is horrid.

I suffered the same, and was often woken up at night by soaking my pillow with a nose bleed. The coughing of the clots afterwards is horrid.![]() Once, he recalled, this happened at school and he asked his teacher not to tell his mom about it, knowing it worried her. …

Once, he recalled, this happened at school and he asked his teacher not to tell his mom about it, knowing it worried her. …

We found harmful chemicals in Lois’s urine samples, too—on July 23, 2019, her sample contained the highest level of naphthalene detected in our study. There isn’t any national data available to compare her level against, but the level of naphthalene detected in Lois’s urine sample that day was more than 15 times higher than the median level we detected in other southwestern Pennsylvania residents.

… “When we do air samples and we do urine samples we don’t usually find naphthalene unless there’s an industrial source releasing naphthalene very close by,” Wilma Subra, an environmental scientist and founder of the environmental consulting firm the Subra Company, told EHN. Through her firm, Subra has spent decades conducting studies similar to EHN’s in communities facing toxic exposures. …

A line of fracking wastewater trucks in Moundsville, West Virginia (Credit: Ted Auch, FracTracker Alliance, 2019)

… Last year, it was discovered that a municipal sewage plant in nearby Belle Vernon was unknowingly accepting and releasing untreated fracking leachate from a nearby landfill containing high levels of chlorides, barium, and radium at higher levels than federal drinking water standards allow into the Mon—one of many similar instances across the state.

At the beginning of the summer of 2019, EHN collected water samples from three locations in the Bower-Bjornson’s family’s home: The reverse osmosis-filtered kitchen tap, the bathtub faucet, and the outside hose spigot. We found detectable levels of 20 of the 40 chemicals commonly used in fracking that we looked for in samples from at least one of those locations, including benzene, which is known to increase cancer risk, and naphthalene, which is listed as “possibly carcinogenic to humans” by the EPA.

… The Bower-Bjornsons had 5.83 micrograms per liter of naphthalene in their water—nearly 12 times as high as Vermont’s health advisory limit. Tri-County Joint Municipal Authority declined to comment on these findings.

Lois, who has been tracking the kids’ symptoms since the drilling began, said that seeing these test results confirmed what she already feared.

“[Fracking] just completely encompasses us,” she said. “It’s not like we can look to our right or left and say it’s not there. And everywhere that they go, school or wherever, it’s there too.”

… The fracking process typically involves as many as 1,000 chemicals including solvents, surfactants, detergents, and biocides, and air monitoring studies have detected more than 100 chemicals in air emissions from the sites, including benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, and mercury. A 2019 study found that air pollution from fracking wells specifically killed an estimated 20 people in Pennsylvania from 2010-2017, and that higher-than-average levels of air pollution can be detected as far as six miles downwind of a well pad.

During the summer of 2019 when EHN collected urine samples from the Bower-Bjornsons, we also had them wear personal air monitors. Each family member wore an air monitor attached to a pump that mimics breathing by pulling in air for six to eight hours leading up to the collection of their first two urine samples. (On a third date, we collected one additional urine sample without any air monitoring.) The samples were analyzed for the presence of 40 chemicals that air monitoring studies have reported as frequently emitted during fracking.

… This issue might be complex for politicians, but for 13-year-old Gunnar, it looks simple. He doesn’t like getting nose bleeds, he doesn’t like his mom worrying, and he’s worried about climate change—which he knows fracking contributes to. “The only reason people don’t think climate change is real is because they’re afraid of it,” he told EHN. “I think fracking is noisy, annoying, reckless, and kind of idiotic. I wish we could move away just to be able to actually get some sleep.” …

****

Part 2: The stress of being surrounded; Jane Worthington moved her grandkids to protect them from oil and gas wells—but it didn’t work. In US fracking communities, the industry’s pervasiveness causes social strain and mental health problems.

… In the spring of 2019, after years worrying about exposures from a fracking well about a half mile from her grandkids’ school, Jane Worthington decided to move them to another school district.

Her granddaughter Lexy had been sick on and off for years with mysterious symptoms, and Jane believed air pollution from the fracking well was to blame. She was embroiled in a legal battle aimed at stopping another well from being drilled near the school. She felt speaking out had turned the community against them.

… Soon after moving in, though, they learned that their new home was within a mile and a half of a well pad with six wells already in production (meaning no longer being “fracked” or drilled, but producing natural gas and oil), and less than a half mile away from a large metal casting facility. An EHN analysis of the air and water at their new home, along with urine samples from the family, suggest they’re being exposed to higher-than-average levels of many of the chemicals they were concerned about at their old house.

“We don’t seem to be able to get away from this,” Jane said.

… Jane and her grandchildren were one of the five families we studied. We collected a total of nine urine samples from the family over a 5-week period and found 18 chemicals known to be commonly emitted from fracking sites in one or more samples, including benzene, toluene, naphthalene, and lesser-known compounds—all of which are linked to negative health impacts including respiratory and gastrointestinal problems, skin and eye irritation, organ damage, reproductive harm, and increased cancer risk.

… The exposures confirm Jane’s worst fears—that the children she’s tasked with protecting are exposed to harmful chemicals simply because of where they live. But the impacts run deeper. The family seemingly cannot escape the effects of an industry that wields tremendous power in the state and is allowed to operate within 500 feet of schools and homes housing children and other vulnerable residents. Researchers warn the impacts extend to the more out-of-sight aspects of health—people’s sleep, their social network, and their overall mental well being.

“I just wish there was more awareness that it really is dangerous for every family that lives here,” Jane said. “It isn’t as safe as we tend to want to make ourselves feel. This is proof.”

When she was in third grade, Lexy became very sick—she developed unusual rashes and had bouts of vomiting. She also developed asthma and started having severe nose bleeds.

After years of unknowns, Lexy’s doctor noticed abnormalities in her growth plates, which led him to believe that her symptoms could be the result of a toxic exposure. A toxicologist found that Lexy had been exposed to benzene, a volatile organic compound (VOC). Because neither her brother nor grandmother were sick—and, seemingly, no other kids at her school—her doctor said she likely had a higher than average sensitivity to benzene.

Benzene is found in tobacco smoke, wood smoke, vehicle exhaust, and industrial emissions. It’s also emitted into the air during both fracking and conventional oil and gas extraction, and is often found in fracking wastewater. Research has found that some workers at fracking sites are regularly exposed to high levels of benzene. Exposure is linked to cancer, organ damage with repeat exposure, fertility issues, skin and eye irritation, drowsiness and dizziness.

… We found benzene in the water at all three locations we sampled at Jane’s house—the kitchen tap, the bathtub faucet, and the outdoor hose spigot. The highest level was in the outdoor hose spigot, which contained benzene at a level of 3.46 parts per billion. This was the highest level of benzene detected in the five households in our study. … “Either way,” Kassotis explained, “outside samples from a hose spigot are usually more reflective of what’s coming from the water authority or groundwater in your region.”

… The family’s exposure to other compounds was higher than average, too. For example on August 5, 2019, a urine sample from Jane Worthington showed a level of phenylglyoxylic acid, a breakdown product of ethylbenzene and styrene, more than 17 times as high as that of the average cigarette smoker (Jane does not use any tobacco products). … These chemicals can be found in household products, gasoline, and emissions from industrial and fracking facilities. Exposure to them is linked to a variety of negative health outcomes, including eye and skin irritation and respiratory problems.

… Since her first episodes in elementary school, Lexy has had similar symptoms—rashes, nose bleeds, joint pain and stiffness, vomiting, and migraines—on and off, which Jane said have coincided with the times when active drilling or flaring (the burning off of excess natural gas) was happening at well pads near their home or near Lexy’s school. Both active drilling and flaring are associated with higher levels of air pollution and more reported health effects than wells in the production phase.

… At least 21 common fracking chemicals (including many of the ones we found) are also endocrine disruptors, meaning they mimic the body’s hormones. This can lead to numerous negative impacts on reproductive, respiratory, metabolic and immune systems and children’s development.

Carol Kwiatkowski, a professor at North Carolina State University and former executive director of the nonprofit research institution The Endocrine Disruption Exchange, warned that current regulations don’t take this into account because many of these effects occur at very low levels of exposure, which traditional toxicology testing doesn’t measure.

She explained that generally when scientists see adverse health effects at a certain level, they keep dropping the exposure lower and lower until they no longer see those effects. Then they set an exposure limit a hundred or a thousand times lower than that.

“They think they’re being extra cautious,” Kwiatkowski told EHN, “setting our safe exposure level so much lower than where they saw effects. But they never test that level. It’s just an assumption that it will be safe.”

Ultimately, Kwiatkowski said, this means that being exposed to some of these pollutants at any level isn’t safe—even if they’re seen at levels well below existing legal thresholds.

****

Part 3: Distrustful of frackers, abandoned by regulators; “I was a total cheerleader for this industry at the beginning. Now I just want to make sure no one else makes the same mistake I did. It has ruined my life.”

… In fracking towns across the state and country, people like Bryan have struggled to get answers about what’s happening on their land, in their communities—even in their bodies. The state agencies tasked with overseeing the industry and responding to citizen complaints about pollution and health issues are often under-budgeted, understaffed, and overwhelmed.

… At a press conference about the grand jury report in July, Attorney General Shapiro said “DEP and DOH have failed Pennsylvanians, particularly during the early years of the fracking boom.”

This pattern has left many residents feeling that even when their complaints are investigated, the results can’t be trusted. A 2017 investigation by Public Herald journalists found that of the more than 4,100 oil and gas-related drinking water complaints filed by residents over a 13-year period, the PA DEP ruled that water contamination occurring near wells was not related to oil and gas activity 93 percent of the time.

Bryan Latkanich’s complaints were among them. In repeated investigations over the years, the DEP acknowledged that Bryan’s water was contaminated, but ruled that Chevron—the company that drilled, operated, and recently plugged the wells on his property—was not to blame. Chevron has maintained that Bryan’s issues are coincidental and have nothing to do with their wells.

… Up until now, Bryan has gotten little help figuring out what’s wrong from doctors, oil and gas employees, or state agency representatives. In 2019, EHN collected urine samples, along with air and water samples, from five families in southwestern Pennsylvania—including Bryan and his son—and had them analyzed for chemicals associated with fracking.

Now for the first time, Bryan has clear evidence that he and Ryan are being exposed to harmful chemicals.

EHN collected three water samples, four air monitoring samples, and six urine samples over a 5-week period from Bryan and his son Ryan, a precocious redhead who was 9 years old at the time.

We found 12 chemicals that are commonly emitted from fracking sites in one or more of their urine samples, including benzene, toluene, naphthalene, and lesser- known compounds linked to negative health impacts including respiratory and gastrointestinal problems, skin and eye irritation, organ damage, reproductive harm, and increased cancer risk. … All six of Bryan and Ryan’s urine samples exceeded the U.S. 95th percentile for mandelic acid, and phenylglyoxylic acid, both of which are biomarkers for ethylbenzene and styrene. Four of the six samples exceeded the U.S. 95th percentile for trans, trans-muconic acid, a biomarker for benzene.

Exposure to these compounds is linked to eye, skin, respiratory and gastrointestinal irritation; neurological, immune, kidney, cardiovascular, blood, and developmental disorders; hormone disruption; and increased cancer risk.

On July 24, 2019, Ryan had a level of hippuric acid in his urine more than 91 times as high as the U.S. median and nearly five times as high as the U.S. 95th percentile. Hippuric acid is a biomarker that forms when the body is exposed to toluene, which is linked to skin, eye, and respiratory irritation; drowsiness and dizziness; and, with chronic exposure, infertility, reproductive harm, and damage to the nervous system, liver, and kidneys.

On July 24, 2019, Ryan’s urine sample also showed a level of mandelic acid—a biomarker of ethylbenzene and styrene—nearly 42 times as high as the U.S. median and nearly 13 times as high as high as the U.S. 95th percentile. He also showed a level of 4-methylhippuric acid, a biomarker of xylene, nearly 13 times as high as the general U.S. median and nearly three times as high as the 95th percentile for 6 to 11-year-olds nationally.

Bryan’s sample that day also showed a high level of mandelic acid—more than 12 times as high as the U.S. median and nearly four times as high as the 95th percentile.

On August 19th, 2019, Ryan’s urine sample showed a level of trans, trans-muconic acid—a biomarker for benzene, which increases cancer risk—that was more than 28 times as high as that of the average adult cigarette smoker.

“These results are pretty shocking,” Bryan said. “I don’t know what else these exposures could possibly be from except the wells. In summertime when Ryan isn’t in school, we both spend 99 percent of our time right here at home.”

… On August 5, 2019, Ryan’s air monitor recorded the highest levels of benzaldehyde, m/p-ethyltoluene, and 1-dodecanol seen among the 39 air samples EHN collected from five households. Exposure to these chemicals has been linked to dizziness and skin, eye, and respiratory irritation.

“When you have a whole host of chemicals like you found, you have to consider the cumulative impact,” Wilma Subra, an environmental scientist and founder of the environmental consulting firm the Subra Company, told EHN. “You can’t just look at one chemical and say, ‘this was below the health standard so that’s ok’—you have to look at the cumulative impact of the other 20 chemicals present. Even at low concentrations you can have health impacts, and when you add it all together, there can be a severe impact on people’s health.”

Toluene was also detected in both Bryan and Ryan’s air samples, mirroring the high levels of biomarkers of toluene that were found in their urine. The levels of toluene detected in their air samples varied widely from day to day.

“Usually the only time you get a range of toluene like that in the atmosphere is if you’re seeing a plume,” John Graham, a senior scientist with the Clean Air Task Force, told EHN. “This could imply that there’s a source that was emitting toluene and that people were exposed to it on the days when it looks really high.”

… EHN’s investigation also found detectable levels of 12 of the 40 chemicals we looked for in Bryan and Ryan’s water—things like butyl cyclohexane, tetradecane, and naphthalene. … Some states set health advisory limits for chemicals that aren’t officially regulated. Vermont recommends no more than 0.5 micrograms per liter of naphthalene in drinking water to avoid health effects including increased cancer risk. The highest level of naphthalene we detected in the Latkanich’s water was 6.96 micrograms per liter.

… More than once, Ryan has come out of a bath or shower with sores all over his body. When Bryan reported this to the Pennsylvania Department of Health (DOH), the agency suggested Bryan and Ryan stop showering at home and instead shower at the nearest YMCA—which is an almost 30-minute drive one way.

… In the absence of a meaningful state registry for health-related oil and gas complaints, the nonprofit Southern Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project* (EHP) has collected hundreds of complaints of health symptoms experienced by residents of southwestern Pennsylvania who live near fracking wells. In 2017 they analyzed 135 health assessments conducted between 2012 and 2015, and found that the most commonly reported symptoms were sleep disruption, headache, throat irritation, stress or anxiety, cough, shortness of breath, sinus problems, fatigue, nausea, and wheezing.

… In North Dakota, the early fracking boom put tremendous strain on the state’s healthcare system (mostly due to the sudden influx of uninsured workers): The number of traumatic injuries reported in the oil patch increased 200 percent from 2007-2012, ambulance calls in one heavily-fracked district increased 59 percent from 2006 to 2011, and 12 medical facilities in western North Dakota saw their combined debt rise by 46 percent from 2011 to 2012 fiscal years. Texas is facing a rural healthcare crisis that leaves people who live amidst oil wells with limited access to care—more than one-fifth of the state’s 254 counties have only one doctor or none at all. A 2020 report from the Pew Charitable Trusts found that nationwide, at least 179 rural hospitals have closed since 2005—with more than 70 percent closing since 2012.

Bryan also feels that doctors have failed to protect him and Ryan. There are very few medical toxicologists in the greater Pittsburgh region. Bryan called the one his insurance would cover repeatedly for weeks until he managed to get Ryan an appointment with University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Dr. Michael Abesamis in spring of 2018.

The doctor returned a written report stating that Ryan had “possible hydrocarbon exposure,” and advising that as treatment, he should “stay away from his exposure source (the house site—air and water) as much as is possible.”

“So basically the toxicologist’s only advice was to move,” Bryan said, “which we can’t afford to do.”

… Chevron maintains that they’ve operated in good faith, but at this point Bryan doesn’t trust them—or any other fracking company, for that matter. And he isn’t alone.

… Matt Mehalik, executive director of the Breathe Project, a coalition of 46 environmental organizations in the Pittsburgh region, told EHN he was saddened but not surprised by the results of EHN’s research.

“To see this kind of proof that people who have endured terrible health issues have had these kinds of exposures from those bad decisions and actions is heartbreaking,” he said. “What your study has done is the work that someone who actually works for a health agency should probably do.”

While a large body of scientific research has linked living near fracking to numerous health effects, state governments approach these studies in very different ways.

The state of New York banned fracking outright in 2014 on the basis of 400 peer-reviewed studies showing potential health harms from the industry (As of August 2020, there were 2,015 studies indicating potential harm). Other states that have looked to the science on both health and climate change impacts and passed permanent or temporary bans on fracking include Vermont, Washington, Maryland, and Oregon. France, Bulgaria, the Netherlands, Germany, Ireland, Wales, the United Kingdom, Uruguay, Brazil, Colombia, and Costa Rica have also passed fracking bans.

![]() Fabulous photo!!

Fabulous photo!!![]() A 2011 fracking protest in Erie, Colorado. (Credit: Erie Rising/Flickr)

A 2011 fracking protest in Erie, Colorado. (Credit: Erie Rising/Flickr)

In an attempt to close that gap, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment also conducted its own multiyear study that used weather and emissions data from Colorado fracking wells to estimate the levels of harmful chemicals up to 2,000 feet from well pads under various weather conditions—things like high vs. low winds, various temperatures, and precipitation. Their findings, which were published in 2019, were groundbreaking.

“We found that during worst case weather conditions, the levels of emissions for chemicals like benzene and xylene are high enough to cause short-term health effects at every distance we studied—from 300 to 2,000 feet from oil and gas operations,” Richardson explained.

These short-term health effects include things like headaches, nosebleeds, difficulty breathing and dizziness. Richardson noted that the study did not account for simultaneous exposures from multiple well pads or assess potential long-term health effects from these exposures.

… Natural gas flaring emits a slew of toxic chemicals including benzene, formaldehyde, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, acetaldehyde, acrolein, propylene, toluene, xylenes, ethyl benzene and hexane, among others. Exposure to those chemicals is linked to a host of negative health effects including increased cancer risk, respiratory and gastrointestinal irritation, endocrine disruption, and central nervous system damage. Very few studies have been conducted on the health effects of exposure to flaring specifically, but one 2020 study concluded that babies born near natural gas flaring are 50 percent more likely to be premature.

Soon after flaring began, Bryan got sick to his stomach and was diagnosed with inflammation in his intestines. He began losing all his body hair, eventually learning that he’d become sterile, and he was prescribed testosterone shots. He developed neuropathy, a type of nerve damage that causes pain and numbness in the limbs and joints, and he was diagnosed with adult onset asthma. Many of his ailments are ongoing—Bryan has been in and out of the hospital at least five times since February 2018. … “The house is still damaged, our health is still affected, the water’s still not drinkable, and the property isn’t put together,” he said. “I’m glad they’re gone. But I’m still not whole.”

Part 4: Buffered from fracking but still battling pollution

… When Ann and Gillian learned that EHN wanted to study households near fracking and compare them to households further away from well pads, they jumped at the chance to participate. At Protect PT they’d already spent months collecting baseline air quality and noise data in the region so that if fracking wells did eventually come, they’d be able to document how things changed. The nearest active fracking well is about seven miles away from Gillian’s house. The nearest compressor station is about five miles away.

… Ann lives about a mile further than Gillian does from both sites. EHN was seeking families living at least five miles from the nearest well or compressor station in order to compare them with families closer to fracking activity.

While many of the most shocking outliers from our project occurred within the families that are surrounded by fracking infrastructure within two miles of their homes in Washington County, we were surprised by what we found in Ann and Gillian’s families.

We collected a total of 12 urine samples from Gillian’s family and 15 urine samples from Ann’s family over a 4-week period and found 21 chemicals in one or more samples, including benzene, toluene, naphthalene, xylenes, other volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and lesser-known compounds, all of which are linked to health problems.

… On August 21, 2019, Gillian’s daughter Lilly, who was 9-years old at the time, had the highest level of 3-methylhippuric acid, a biomarker for xylene, detected in anyone in our study. Xylene exposure is linked to skin, eye, and respiratory tract irritation, drowsiness and dizziness, and organ damage with high levels of long-term exposure.

“It’s pretty shocking to know that our children, especially, are being exposed to this stuff,” Gillian told EHN. “We take great pains to make sure we’re not exposed to things.”

Gillian and Ryan try to buy organic foods when they can. They avoid contaminants like bisphenol-A (BPA) in plastic and Teflon in cookware, and they installed a reverse osmosis filter at the kitchen tap to make their drinking water as clean as possible. They avoid using cleaning or pest control products with harsh chemicals.

Some concerning chemicals showed up in the familys’ air and water samples, too.

In Gillian’s water, we found detectable levels of 14 of the 40 chemicals we analyzed the samples for, including benzene, toluene, and naphthalene. In Ann’s water, we found detectable levels of 11 of the 40 chemicals we analyzed the samples for. That list also includes benzene, toluene, and naphthalene. …

On August 15, 2019, the five highest levels of both d-limonene and styrene detected in our study were detected in air monitoring samples from the five members of the LeCuyer-Ley household. On the same day, Ann’s husband Mike’s air monitor also detected the highest level of toluene seen in our study.

On the same day, Gillian’s husband Ryan’s air monitor detected the highest levels of 1,2,3-trimethylbenzene, o-diethylbenzene, undecane, m/p-diethylbenzene, decane, and 1,2,4,5-tetramethylbenzene seen in our study.

… A third potential source of exposure is the fracking wells and compressor stations within 10 miles of Ann and Gillian’s homes. Emissions are most concentrated in areas closest to wells, but some studies have found that depending on wind patterns and geography, they may impact communities much further downwind. One study published in May of 2020 documented negative changes in air quality as far as six miles downwind of fracking wells; another study led by Harvard researchers that was published in October of 2020 found increased levels of radiation up to 31 miles downwind of fracking sites.

Finally, both the women’s homes are surrounded by a high volume of conventional oil and gas wells. There are at least 100 conventional wells within five miles of both Ann and Gillian’s homes. Under Pennsylvania law, conventional wells can be within 200 feet of an occupied building in the state, compared to 500 feet for unconventional wells.

… The stories we heard from people living among fracking wells in southwestern Pennsylvania aren’t unique. In similar communities across the country, people struggle with many of the same issues: Physical and mental health symptoms, worry over the long-term impacts of chemical exposures, feeling abandoned by regulators and mistrustful of the fracking companies being left to self-regulate, grieving the industrialization of formerly idyllic countrysides, and feeling alienated and ostracized in communities divided over whether fracking is a boon or a burden.

But the exposures EHN documented in the 20 people in our study suggest that southwestern Pennsylvanians are experiencing higher-than-average levels of harmful pollution—even compared to other fracking communities.

… A 2018 study of 29 pregnant women who live near fracking wells in Canada found trans, trans-muconic acid, a biomarker of benzene, at levels around 3.5 times as high as those seen in the general Candadian population. The median level of trans, trans-muconic acid seen in people in that study was 180 micrograms per gram (µg/g) of creatinine (a substance measured to account for different metabolic rates when looking at biomarkers). The median for the U.S. as a whole, according to CDC data, is 77 µg/g. The median level seen in our study was 484 µg/g—nearly three times as high as the level seen in the Canadian study.

“l saw that the levels of trans, trans-muconic acid you saw in your study were quite a bit higher than what we found,” Élyse Caron-Beaudoin, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto Scarborough and the lead author of the Canadian study, told EHN after reviewing our findings. “And we certainly thought the levels seen in our study were quite high.”

A 2016 study in Pavillion, Wyoming tested urine samples for 11 farmers who live near fracking wells and found elevated levels of biomarkers for many of the same chemicals we looked for—but in most cases, the levels we detected in Pennsylvania were significantly higher.

The median levels we detected for 8 of the 11 biomarkers we looked for were higher in Pennsylvania than those seen in the Wyoming study; the maximum levels we detected were higher for 7 out of 11 compounds. In many cases the gaps were substantial. …

LEARN: More about how we conducted our study

Listen to Kristina Marusic discuss the “Fractured” investigation

***

Follow the fallout from this investigation: #FracturedUSA

Refer also to:

2014: Karla Labrecque’s doctor refused to do a blood test until he consults with a local politician; Mike Labrecque gets sick working for Baytex, Baytex lets him go: “You’re done.” Under Harper-Kenney UCP in Alberta, health care has become much worse, with Minister of Health Shandro arriving in your driveway to scream at you, if you say something he doesn’t like, and he, like all dutiful UCP, love polluting oil & gas.

2013: Canada’s historic drilling/frac’ing chemical list by PSAC (as usual, after I went public with it, PSAC removed it off their website so I uploaded it here)