Interesting comments by readers and their slap downs of a few lying shills to Nikiforuk’s article, click on link to read them:

‘Red Flag’ Raised: Study Finds Possible Fracking Risk to Pregnant BC, Women, Researchers found markers suggested benzene levels 3.5 times normal levels for women in northeast by Andrew Nikiforuk, November 16, 2017, The Tyee

A small pilot study by researchers from the Université de Montréal has raised red flags about pregnant women’s exposure to benzene in intensely fracked areas of northeastern B.C.

The study found that the median level of muconic acid in urine samples from 29 pregnant women in the region was 3.5 times higher than the general Canadian population. Muconic acid is a common bio-marker of benzene exposure.

“Prenatal exposure to low environmental levels of benzene or a mixture of organic solvents has been associated with reduced birth weight, increased risk of childhood leukemia and birth defects such as cleft palate and spina bifida,” the researchers note.

Benzene is also one of many contaminants that can be emitted during drilling, fracking or flaring of waste gas from thousands of oil and gas sites.

But Marc-Andre Verner, a toxicologist and professor at the Université de Montréal Public Health Research Institute (IRSPUM), hastened to add that the study wasn’t designed to locate the source of the benzene.

“There is a red flag being raised here,” he said, but it “remains unknown” whether the study results can be attributed to benzene emissions from oil and gas activity in the region.

He also warned that muconic acid in the urine can also originate from the degradation of sorbic acid, a common preservative used in highly processed foods.

The study concluded more research is needed to assess the health risks to pregnant women from fracking.

“Given the documented health effects of benzene, especially those occurring through in utero exposure, and the growing hydraulic fracturing industry in this region, this first biomonitoring initiative certainly highlights the need of further research to better delineate associated health risks,” researchers said.

Verner and a post-doctoral student decided to do the study after a member of the West Moberly First Nation raised concerns about the public health impacts of heavy fracking at a national toxicology conference several years ago. Participants were recruited from clinics in Chetwynd and Dawson Creek.

Nearly half of the participants in the study were Indigenous women who live closest to oil and gas activity in the region.

The study found that “the median concentration of muconic acid in the urine of these 14 women was 2.3 times higher than in non-Indigenous participants, and six times higher than in women from the general Canadian population.”

Verner and his team have applied for funding to do a larger study with 100 pregnant women that would measure volatile organic compounds and heavy metals in air and drinking water in addition to bio-markers.

In the meantime Élyse Caron-Beaudoin, a post-doctoral student who participated in the research, plans to examine the medical records of 6,000 babies born in the last 10 years.

In the last decade thousands of shale gas wells in the region have been subjected to the brute force technology of hydraulic fracturing in order to wrest natural gas liquids (butane and pentanes) and methane from the Montney and other unconventional shale formations in northern B.C.

Other studies have identified concerns about the public health risks of fracking.

In Pavillion, Wyoming, a region of intense hydraulic fracturing activity, researchers have detected elevated benzene concentrations in air near homes located close to well pads. They have also found high muconic levels in urine as a result of benzene exposure.

Benzene, a colourless gas that can cause cancer, is just one of hundreds of toxic chemicals that can be emitted at shale gas drilling and fracking sites. Many oil and gas workers are routinely exposed to the deadly carcinogen.

For years public health researchers have been raising red flags about chemicals emitted by hydraulic fracturing and flaring.

More than 90 per cent of new wells require fracking. The brute force technology blasts large volumes of water, chemicals and sand up to three kilometres below the surface to crack open hydrocarbon-bearing rock. The operation can industrialize rural communities with truck traffic, noise, holding ponds and air pollution.

In 2015 researchers at Johns Hopkins University reviewed the records of nearly 11,000 births between 2009 and 2013 in heavily fracked rural areas of north and central Pennsylvania.

The researchers discovered that expectant mothers living in the busiest areas of shale gas activity were 40 per cent more likely to give birth prematurely (before 37 weeks of gestation).

In addition women were thirty per cent more likely to have a “high risk pregnancy” in heavily fracked landscapes.

And in 2014 as U.S. federal study found that pollution from the mining of natural gas in rural areas can increase the incidence of congenital heart defects among babies born to mothers living close to well sites.

More than 17 organizations, including the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, have called for a public inquiry on hydraulic fracturing in B.C. due to concerns about methane leaks, groundwater contamination, large water withdrawals and fragmentation of First Nation land.

The shale gas industry has triggered thousands of mini-earthquakes along with significant tremors and changed seismic patterns in the region.

Seismic hazard experts have called for better regulations and no-go zones to protect public infrastructure in the region such as dams.

BC Fracking May Be Exposing Pregnant Women to a Carcinogen, Study Says, Urine tests suggest higher than normal levels of a benzene near shale gas fields by Sarah Berman, November 21, 2016, Vice

Ever since former premier Christy Clark stepped out of the public eye earlier this year, British Columbians haven’t been hearing too much about the liquified natural gas sector her government built and subsidized. What seemed like a lot of bragging and bending to international investors a few months ago has been replaced with Premier John Horgan’s much quieter investment pursuits.

Now a pilot study from Université de Montréal researchers has reminded us there’s still a lot we don’t know about shale gas extraction in northeastern BC. Specifically, there’s not a lot of science digging into how fracking-related chemical exposure in the region might be impacting local people’s health.

… Elyse told VICE that companies don’t have to publicly disclose exactly what chemicals they are mixing, and that toxicity data doesn’t exist for hundreds of them.

The researchers tested urine samples of 29 pregnant women in Chetwynd and Dawson Creek, two small communities near heavily-fracked shale gas fields in BC’s Peace River Valley. They measured two “biomarkers” that our bodies produce when we’re exposed to benzene, a carcinogen that’s been linked to low birth weights and some defects.

Caron-Beaudoin told VICE benzene is a byproduct of any combustion—so smoking cigarettes or driving around the city will also cause some exposure. But the research findings, which will appear in the January issue of Environment International, suggest that exposure levels in these remote communities fall outside what’s normal.

Caron-Beaudoin says her team found the women’s urine samples had 3.5 times more of these biomarkers than the average Canadian. Of the women who identified as Indigenous, those markers were six times more concentrated. But because the sample size is so small, the authors say more research is needed to be sure benzene is really the cause.

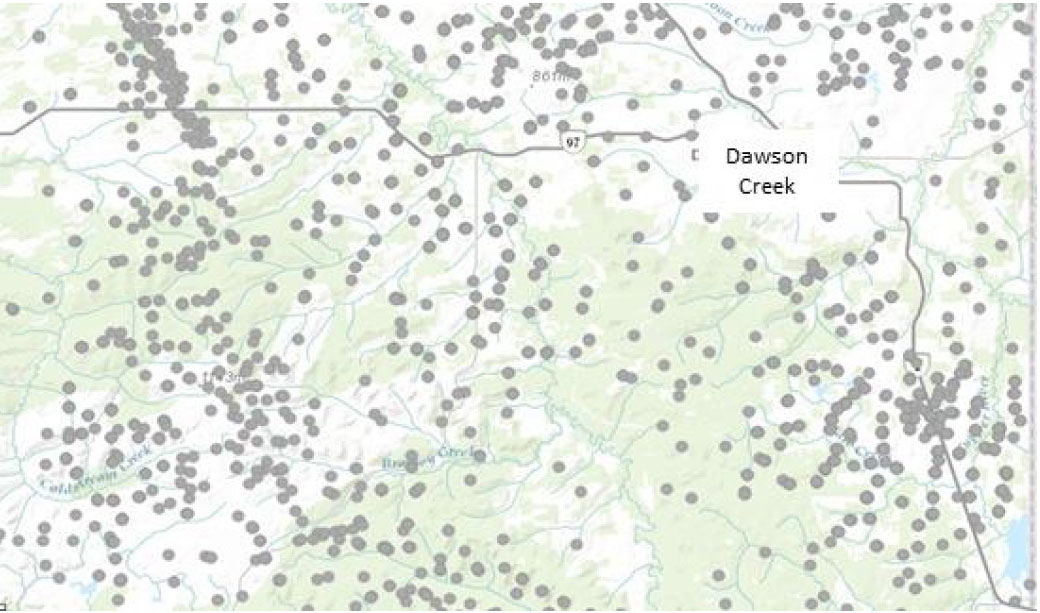

Fracking wells near Dawson Creek, BC. Image via Environment International

The researchers chose benzene biomarkers because the Canadian government already has solid data on it, and it’s much easier to test for than benzene itself. “Because benzene is volatile and those tests need to be done quickly, we decided it’s not possible to measure benzene directly in urine,” Caron-Beaudoin told VICE. “With those little molecules it’s easier to freeze the samples and analyze later.”

But, Caron-Beaudoin says this isn’t a perfect indicator, because some food preservatives also create the same biomarkers when our bodies try to break them down. “It’s not 100 percent specific to benzene, but it gives a good idea,” she said, adding diet or second-hand smoke exposure alone were unlikely to account for such high concentrations of the markers.

“What we will do, is we will look at associations between density and proximity of fracking wells and some birth outcomes in the past 10 years in northeast BC,” she said. “So looking at birth weight, gestational age, which gives an idea of preterm birth or not, head circumference, and birth defects.”

When complete, the study will be the first of its kind in Canada. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to: