Twelve Angry (White) Men: The Constitutionality of the Statement of Principles by Joshua Sealy-Harrington, Jan 1, 2020, Ottawa Law Review Volume 51, Issue 1  Footnotes not included below, access them via link or the PDF

Footnotes not included below, access them via link or the PDF

This paper analyzes the constitutionality of the Law Society of Ontario’s (now repealed) Statement of Principles requirement. First, this paper conducts a statutory analysis of the requirement. It explains how the requirement merely obligated that licensees acknowledge extant professional and human rights obligations, rather than creating novel obligations. Second, this paper conducts a theoretical analysis of the requirement. It applies a critical race theory lens to unveil the ways in which liberty claims relating to free speech obscured how significant resistance to the requirement’s modest obligation was galvanized by opposition to diversity and denial of systemic racism. Third, this paper conducts a constitutional analysis of the requirement.

It explains why the requirement did not violate freedom of conscience or freedom of expression. In contrast with prior scholarship, this paper argues that the Statement of Principles requirement failed every stage of the legal test that designates state activity as compelled speech.

Specifically, the requirement failed to compel an expression with non-trivial meaning (Step 1) and failed to control free expression in Canada, when such control is properly construed through a purposive rather than colloquial lens (Step 2). This paper concludes by noting how the requirement’s self-drafted structure provided an innovative opportunity for licensees to reflect on their perhaps unwitting participation in systemic racism.

The other thing that disturbs me about this, and I suppose this is a consequence of my experience with delving deeply into the history of places like the Soviet Union in its early stages of development is that there’s a class-based guilt phenomena that’s lurking at the bottom of this, which is also absolutely, I would say, terrifying.— Jordan Peterson1

My first instinct was to check my passport. Was I still in Canada, or had someone whisked me away to North Korea, where people must say what officials want to hear?—Bruce Pardy2

This is the cultural enemy that has arisen within, after Western civilization routed the largely external and outright evils of Nazism and international Communism … the law society is conferring capricious dictatorial powers on its own administration … —Conrad Black3

The chilling Orwellian language bears repeating … Forcing lawyers to subscribe to a particular worldview for regulatory purposes is an unacceptable intrusion into a lawyer’s liberty and promotes significant harm to the public.—Arthur Cockfield4

[A] breed of hyper-progressive social activists who feel justified in co-opting the prerogatives of a regulatory monopoly as a means to force white-collar workers to lip-sync doctrinaire liberalism. It’s creepy. It’s coercive. It’s presumably unconstitutional. And it’s an embarrassment to the law society.— Jonathan Kay5

Now the Law Society is demanding that I openly state that I am adopting, and will promote, and will implement “generally” in my daily life, two specific and pretty significant words or “principles,” words that are quite vague but sound important. When I first read that a year ago I was completely floored. What is going on here? This sounds like I’m supposed to sign up to some newly discovered religion, or some newfangled political cult.— Murray Klippenstein6

[T]here is one reason above all others why Ontario lawyers should not only refuse to sign on to the Law Society’s “progressive agenda” but they should send the current Society’s head office packing. That is the principle of “merit.” Because most lawyers believe that a person should be hired, evaluated, and promoted solely on merit, and not on superficial criteria like ethnic origin, race, or gender, this view places these professionals in contravention to the “progressive agenda” of their professional association. To the Society, everything is about race and gender. That is simply wrong.— Brian Giesbrecht7

Special interest groups have gained a foothold in convocation. They seek to erase our history, mandate ideological training and implement discriminatory race and sex-based quotas. I will stand up to special interest groups to defend our profession’s proud traditions and values.— Nicholas Wright8

[T]his Initiative by the LSO is profoundly disturbing … It has certainly awoken the spirit of vigilance in me. In my view, it requires all lawyers of conscience to oppose this initiative in order to maintain and protect the cherished independence and liberties lawyers have inherited and to which they have been entrusted.— Michael Menear9

If the requirement that I hold and promote values chosen by the Law Society is not repealed or invalidated, I will cease being a member of the legal profession in Ontario. This is not an outcome I desire … However, I simply cannot remain a member of the legal profession in Ontario if to do so would violate some of my most deeply held conscientious beliefs.—Leonid Sirota10

The requirement is … the result of political ideology, rather than any evidence-based process, and … deeply offensive to me personally in terms of its clear implication that I and my profession and society are racist.—Alec Bildy11

As Shawn Richard, one of the architects of the Law Society’s policy, asked: “What are you conscientiously objecting to?” … It’s easy to forget that decades of progress can be wiped out in an instant. Citizens who belong to religious groups subjected to significant persecution — especially those who have recently arrived as refugees from totalitarian states — can easily imagine the dangerous consequences of a values test compelled by forced speech … I hope that as a cranky old white man I can make myself useful by defending their rights.—Ryan Alford12

I. INTRODUCTION

The twelve impassioned quotes above concern a requirement that Ontario lawyers annually draft a statement reflecting on their professional and human rights obligations pertaining to diversity. Equality, it seems, is a divisive ideal; so divisive, in fact, that while the requirement was in force during the drafting and peer-review of this article, it was repealed on the same day my final revisions were due to the Ottawa Law Review. The evasive rationale behind opposition to this requirement was, most often, freedom of speech. I explain below, principally, how the requirement does not violate freedom of speech, and secondarily, how its opposition was not really about freedom of speech in any event. The Law Society of Ontario (LSO) previously required all lawyers to “adopt and to abide by a statement of principles.”13 The sole requirement of any Statement of Principles (SOP) was that it must acknowledge the lawyer’s “obligation to promote equality, diversity and inclusion.”14

Two lawyers — Ryan Alford and Murray Klippenstein — applied to judicially review the SOP requirement (Application).15 That Application alleged that the SOP requirement, among other things, violated lawyers’ constitutional right to free speech by “compel[ling] licensees to communicate political expression.”16

This paper explains why, to the contrary, the SOP requirement does no such thing.17 While there was active public debate regarding the merits of the SOP requirement, there was relatively less substantive constitutional analysis: to date, there are three articles published by Omar Ha-Redeye,18 Arthur Cockfield,19 and Justin P’ng.20 I dispute aspects of the constitutional analysis in all three articles, and think each gives under-served credit to the constitutional significance of privately acknowledging extant legal obligations.

My analysis proceeds in three parts. First, I conduct a statutory analysis, including an explanation of the background to the SOP requirement. This statutory analysis is an essential antecedent inquiry to interpreting and resolving the SOP controversy. Two ships cross paths in this dispute as to the proper statutory interpretation of the SOP requirement: a right-bound ship requiring that lawyers value equality (SOP opponents) and a left-bound ship requiring that lawyers acknowledge existing equality law obligations (SOP proponents). We cannot assess the SOP critically or constitutionally without first choosing which ship best reflects the enacted text. And as I explain below, the left-bound ship better reflects the text, context, and purpose of the SOP requirement. Second, having chosen the left-bound ship, I then interpret the SOP controversy through a critical race theory lens. I explain how liberty claims — here, “free speech” — obscure the apparent motivation for sustained resistance to the modest SOP requirement, namely, opposition to diversity and denial of systemic racism. Third, I assess the SOP requirement’s constitutionality. After briefly explaining why the SOP requirement respects freedom of conscience (since brief voluntary reflection about following the law trivially impacts freedom of conscience), I then explain why the SOP requirement respects freedom of expression by: (1) clarifying the purposive scope of free expression; (2) distilling the legal test for unconstitutional compelled speech; and (3) applying that test to the SOP requirement.

I conclude that the SOP requirement does not violate free expression under Canadian constitutional law because it does not seek to convey meaning, nor does it — in purpose or effect — control free expression.

It follows that, while the SOP requirement is now repealed, the motivation for that repeal — protecting speech (text) and resisting equality (subtext) — was doctrinally flawed.

II. STATUTORY ANALYSIS

A. Why the SOP Was Adopted

Systemic racism is a problem in Canada,21 despite views to the contrary.22 Articles abound illustrating systemic racism’s reach within Canada’s justice system,23 and similarly, the legal profession.24 With this concern in mind, the LSO established a Working Group on Challenges Faced by Racialized Licensees (Working Group)25, which “studied the experience of racialized licensees” and found they faced “widespread barriers.”26

After “broad consultation within the legal profession and with the general public,” the Working Group produced a report titled “Working Together for Change: Strategies for Addressing Issues of Systemic Racism in the Legal Profession” (Report).27 That Report made 13 recommendations, including the introduction of the SOP requirement.28 The LSO (then named the Law Society of Upper Canada)29 ultimately adopted all 13 recommendations.30 One commentator labeled this a “hurried and flawed process” rife with “bullying tactics.”31 However, given the absence of any alleged link between this process and the SOP requirement’s impugned constitutionality, I do not respond to these claims here.

The LSO incrementally introduced the SOP into its regulatory scheme. In September 2017, the LSO “notified all licensees that they would be required to confirm that they had adopted a [SOP] in their [annual report].”32 In November 2017, the LSO published a “Guide to the Application of Recommendation 3(1)”33 (the Guide), meant to assist licensees in fulfilling their SOP obligations.34

That same month, the LSO advised licensees that there would be no sanctions for failing to comply with the SOP requirement in annual reports for 2017.35

During the SOP’s abbreviated life cycle, the LSO never imposed or signalled any intent to impose sanctions for non-compliance with the SOP requirement, and simply indicated that licensees who failed to comply “will be advised of their obligations in writing.”36

B. What the SOP Required

According to the LSO’s materials, the SOP was simply an acknowledgement of extant obligations — that “[t]he requirement will be satisfied by licensees acknowledging their … existing legal and professional obligations.”37 In stark contrast, the Applicants characterize the SOP as a creator of novel obligations.38 In my view, the former characterization best reflects the text, context, and purpose of the SOP requirement. In turn, as the SOP was anchored in extant legal obligations, analogizing it with values tests divorced from such obligations is inapt.39

It was, however, strategic for SOP opponents to mischaracterize the SOP’s regulatory scope to advance a narrative of regulatory overreach.

Indeed, a quirk of the SOP controversy is how both sides never reached agreement on the scope of the SOP, and thus, never meaningfully engaged with each other on the SOP’s constitutionality. As I explain below, I interpret the SOP to be a mere regulatory acknowledgment.

Accordingly, anti-SOP advocates, it seems, manufactured a phantom SOP requirement, and then leveraged that mythology for rhetorical purposes. ![]() A fabricated phantom killed my lawsuit, tossing it, me, and the public interest in the trash!?!

A fabricated phantom killed my lawsuit, tossing it, me, and the public interest in the trash!?!![]()

Snap above taken in 2019 from Joshua Sealy-Harrington’s twitter

In my understanding, no one argued in favour of regulating licensees’ thoughts about equality; yet most, if not all anti-SOP advocates, presupposed such thought regulation to justify their constitutional posturing. They were thus, ironically, the architects of their own contrived oppression.

![]() Klippenstein’s betrayal has been one of the worst of my life, and I’ve experienced a lot of betrayals by spoiled angry white men.

Klippenstein’s betrayal has been one of the worst of my life, and I’ve experienced a lot of betrayals by spoiled angry white men.![]()

To interpret the SOP requirement, we must begin, of course, with its text, described by Cockfield as “chilling Orwellian language.”40 In his analysis, Cockfield isolates the phrase “statement of principles” when interpreting the scope of the SOP requirement.41 This truncated analysis, however, deviates from established principles of statutory interpretation.42 The full text of the requirement reads as follows: “The Law Society will … require every licensee to adopt and to abide by a statement of principles acknowledging their obligation to promote equality, diversity and inclusion generally, and in their behaviour towards colleagues, employees, clients and the public.”43 Three points follow from the plain text of the SOP requirement: (1) it was mandatory, not optional (“require”);44 (2) it was an ongoing, not intermittent, obligation (“adopt” and “abide”); and (3) it was an acknowledgement of extant obligations, rather than a creator of novel obligations (“acknowledging their obligation”).45

That the SOP requirement was explicitly framed as an “acknowledgement” does not end the discussion. For example, if the SOP requirement mandated lawyers to conduct activities clearly outside existing obligations — e.g. to “acknowledge their obligation to discriminate against female articling students” — few scholars would respond that it is simply administrative. Indeed, such an acknowledgment would run directly counter to lawyers’ obligations not to discriminate in their employment practices.46 But, on a textual basis, the SOP requirement appears to have been an acknowledgment of extant legal obligations. And, as I will explain, given that the subject of the acknowledgment — obligations “to promote equality, diversity and inclusion” — fell within the scope of extant professional and human rights obligations, the strongest interpretation of the SOP requirement is that it did not modify those obligations. Put differently, if there are two reasonable textual interpretations of the SOP requirement — one that links the requirement to extant obligations, and one that links the requirement to novel obligations — then the former interpretation is stronger because it is more logical for an acknowledgment to relate to existing obligations.

The Guide reinforces the characterization of the SOP requirement as a mere acknowldgement. While I recognize that the Guide, unlike the SOP requirement, is not the product of Convocation, it is cited extensively by the Applicants and their supporters and thus warrants some discussion.47

The Guide repeatedly affirms the view that the SOP requirement created no new obligations, but instead, acknowledged existing ones: that it “reinforces existing obligations in the Rules of Professional Conduct”;48 that it pertains to “human rights laws in force in Ontario”;49 that it “does not create any obligation … [but] will be satisfied by licensees acknowledging their obligation to take reasonable steps to cease or avoid conduct that creates and/or maintains barriers for racialized licensees or other equality-seeking groups”;50 that “[t]he reference to the obligation to promote equality, diversity and inclusion generally refers to existing legal and professional obligations in respect of human rights”;51 and that “[t]he content of the Statement of Principles does not create or derogate from, but rather reflects, professional obligations.”52 This remains, of course, the LSO’s framing. However, it is difficult to fathom the LSO seeking to impose novel obligations originating with the SOP — the Applicants’ central concern53 — when the LSO has repeatedly and expressly opined to the contrary, and in a manner that could presumably be used in legal defense against the imposition of any such novel requirements in the future.

That the SOP requirement pertained to licensees’ obligations in terms of conduct, not thought, follows from the requirement’s phrasing. It referred to an “obligation to promote equality, diversity and inclusion generally, and in their behaviour towards colleagues, employees, clients and the public.”54 On a truncated reading, one could argue that requiring lawyers to “promote equality” per se, demanded that they advocate for equality in their free time. But, when read as a whole, the emphasized language above — “in their behaviour” — suggests that the requirement to “promote equality” referred to ways in which one’s “behaviour” (e.g. sexually harassing female colleagues) can impede (i.e. not promote) equality.55

In this sense, the SOP requirement was more performative than declaratory; it required an acknowledgment of each licensees’ obligation to act in accordance with extant obligations (in the hiring and treatment of employees, the provision of legal services, etc.), not that licensees think anything preordained about those obligations.

Lastly, the principle that absurd interpretations should be rejected56 favours an interpretation of the SOP requirement that does not extend to proselytizing equality. For example, Leonid Sirota writes that, on his interpretation of the SOP requirement, he is obligated to “devote [his] scholarship to the promotion of equality.”57 But it would be absurd to think that the LSO — with a view to serving the “public interest”58 — created the SOP requirement, not only to ensure that all academic writing on equality adopted a homogenous position, but further, that all academic writing on any topic was directed exclusively towards advancing progressive equality principles. Surely the public interest is best served through diverse academic discourse on a range of topics, including those that have nothing to do with equality. Yet that is precisely what follows from the interpretation adopted by its critics. Indeed, those critics openly admit that the interpretation they advance “leads to a variety of absurdities.”59 Their analysis is, thus, self-defeating. Similarly, if the interpretation of the SOP advanced by its critics prohibits lawyers from zealously advocating for their clients — an ethical obligation with constitutional significance60 — that is all the more reason to reject this interpretation, not accept it.

The mechanics of the SOP attenuated — if not eliminated — any residual concerns about its “vaguely authoritarian” nature.61 Unlike lawyers’ Required Oath, which has prescribed content,62 the SOP was individually drafted by each licensee. While the LSO provided two sample templates to assist licensees,63 those licensees “[were] not limited to these templates and [were] not required to adopt either of them.”64 This was clear in the text of the SOP requirement itself, requiring that each licensee “adopt and to abide by a statement of principles,”65 not one drafted or authorized by the LSO. Even further, the SOP was modestly enforced. While the SOP was in effect, abstainers, at worst, received a reminder letter from the LSO.66

In sum, the SOP requirement mandated nothing more than “acknowledging” one’s extant professional and human rights obligations.67

The following, then, would have met the requirement: “I acknowledge my existing professional and human rights obligations.”68

![]() Mr. Klippenstein treated me like shit for such a trivial LSO requirement?

Mr. Klippenstein treated me like shit for such a trivial LSO requirement?![]()

That is what this controversy boils down to — the textual equivalent of checking a box next to an identical administrative phrase in an annual reporting form. However, one could go even further. While the SOP “need not include any statement of thought, belief or opinion,”69 it certainly could70 — and that statement could have been as critical of the SOP, or equality rights generally, as the author desired.71 As noted, the SOP requirement only demanded that every SOP include an acknowledgment of existing regulatory obligations, not that it exclude any other content.72

Accordingly, the following statement would have also met the SOP requirement:

I hate equality. I hate diversity. And I hate inclusion. The only thing our legal profession should care about is merit. And reverse discrimination initiatives that are founded on the Statement of Principles’ ideology tokenize minorities, alienate broad coalitions, and punish white men (including Jewish men) for the sole fact of their birth.

Roaring laughter! If white men only knew how fortunate they are compared to women and non whites.

The tyrannical Statement of Principles is a useless half-assed attempt at PC thought control that is intolerable in a liberal society. The Law Society of Ontario should be ashamed for buying into the misguided far-left zeitgeist.

I begrudgingly acknowledge my existing professional and human rights obligations, but only because I am compelled to, and in no way out of a sincere belief that diversity — whatever that means — is important, or some-thing the Law Society has any business concerning itself with in any event.

It follows that near limitless protest can be built into any given SOP should its author — in “good conscience”73 — so desire. In the words of Annamaria Enenajor, even a “closet neo-nazi” could draft an acceptable SOP.74 Further, the LSO does not scrutinize SOPs.75 There is no obligation on any lawyer to publicize their SOP, or to even disclose it to the LSO;76 lawyers need only “confirm its existence.”77 Therefore, while the SOP had a modest requirement (i.e. acknowledging extant obligations), the LSO provided no substantive oversight.

The Applicants claimed that meeting the SOP requirement — drafting virtually whatever statement they wanted, which no one would ever read — forced them “to cease practicing law.”78

![]() I’ve never laughed (but also cried at the same time) so hard in my life. Too ridiculous. These are lawyers we retain, put our faith in and pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to, only to be pissed on for such a foolish reason? Angry Spoiled Rotten Privileged White Men.

I’ve never laughed (but also cried at the same time) so hard in my life. Too ridiculous. These are lawyers we retain, put our faith in and pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to, only to be pissed on for such a foolish reason? Angry Spoiled Rotten Privileged White Men.![]()

Given the wide latitude afforded to licensees in meeting this modest requirement, abandoning legal practice strikes me as disproportionate.79 At a minimum, if this dispute had ever reached the justification stage of the constitutional analysis — which, as I argue below, it should not — I strain to think of a more trivial incursion on free expression (which, in turn, strongly favours that incursion’s demonstrable justification in a free and democratic society).80 In Ha-Redeye’s words: “[i]f that’s not minimal impairment, I’m not sure what is.”81

C. Whether the SOP Reflected Extant Obligations

Still, the question remains: even if the SOP requirement was a mere acknowledgement of pre-existing obligations, are those obligations truly extant?82 In other words, do alternate instruments actually require lawyers to “promote equality, diversity and inclusion generally, and in their behaviour towards colleagues, employees, clients and the public”? A review of the relevant human rights and regulatory instruments confirms that this is indeed the case. Justin P’ng provides a compelling argument for how the LSO has diversity promotion obligations within its regulatory mandate,83 and I agree with his points. In contrast, my analysis below clarifies how licensees, too, have diversity promotion obligations — the very obligations acknowledged by the SOP requirement.

The scheme of human rights and regulatory instruments applicable to licensees imposes requirements for promoting equality both “generally” and in “professional” behaviour. I will address these two settings below. That said, my thesis in respect of both is the same: reasonable mindfulness of barriers to equality-seeking groups is an established legal obligation. The Applicants rely on a strawman: that these equality promotion obligations require all lawyers to shout their love for minorities from the rooftops.84 However, this attack disregards the positive scope of pre-existing human rights obligations in Canada.

One word — “promote” — seems to be what concerns free speech advocates most.85 They accept that lawyers cannot discriminate ![]() But some seem to, and worse, get away with it.

But some seem to, and worse, get away with it.![]() in practice86 (though some anti-SOP advocates even consider this overreach),87 but balk at the state requiring equality promotion, which they interpret broadly as requiring active equality campaigning. I acknowledge that, when read in isolation, “promote” connotes actively encouraging acceptance of progressive equality ideals.88 But this word must be read, as I explained above, in the context of the full by-law and the setting of legal regulation. With this in mind, I have three responses to the claim that the SOP requirement’s use of “promote” should be read so broadly. First, as the Guide explains: “[e]quality, diversity and inclusion are promoted (in other words, advanced) by addressing discrimination in all of its forms.”89 Thus, even on a purely negative liberty conception of Canadian equality rights, prohibiting overt discrimination is a means of equality promotion.90 Second, promotion can simply mean to “support.”91 The Canadian conception of non-discrimination is expansive enough to include “support” (e.g. accommodation) of minorities and not just restrictions on overt and targeted formal discrimination, a diluted understanding of discrimination.92 SOP critics claim that the state cannot justifiably impose positive obligations per se.93 But unless those same critics are willing to challenge, for example, reasonable accommodation standards in human rights and employment law94 — an unequivocally positive obligation95 that is “a core and transcendent human rights principle”96 — they cannot escape that their opposition to the SOP is predicated on an antiquated conception of equality rights, not a strident defence of free speech.97 Third, the word “promote” must be interpreted in context. For example, Cockfield draws on judicial interpretations of “promote” in hate speech case law.98 But there, as here, a purposive analysis must be employed. Indeed, as Chief Justice Dickson explained in R v Keegstra: “[g]iven the purpose of the provision to criminalize the spreading of hatred in society, I find that the word ‘promotes’ indicates active support or instigation.”99 In stark contrast, the purpose of proactive regulatory compliance here demands a narrower purposive interpretation of “promote” to align that interpretation with the relevant context.

in practice86 (though some anti-SOP advocates even consider this overreach),87 but balk at the state requiring equality promotion, which they interpret broadly as requiring active equality campaigning. I acknowledge that, when read in isolation, “promote” connotes actively encouraging acceptance of progressive equality ideals.88 But this word must be read, as I explained above, in the context of the full by-law and the setting of legal regulation. With this in mind, I have three responses to the claim that the SOP requirement’s use of “promote” should be read so broadly. First, as the Guide explains: “[e]quality, diversity and inclusion are promoted (in other words, advanced) by addressing discrimination in all of its forms.”89 Thus, even on a purely negative liberty conception of Canadian equality rights, prohibiting overt discrimination is a means of equality promotion.90 Second, promotion can simply mean to “support.”91 The Canadian conception of non-discrimination is expansive enough to include “support” (e.g. accommodation) of minorities and not just restrictions on overt and targeted formal discrimination, a diluted understanding of discrimination.92 SOP critics claim that the state cannot justifiably impose positive obligations per se.93 But unless those same critics are willing to challenge, for example, reasonable accommodation standards in human rights and employment law94 — an unequivocally positive obligation95 that is “a core and transcendent human rights principle”96 — they cannot escape that their opposition to the SOP is predicated on an antiquated conception of equality rights, not a strident defence of free speech.97 Third, the word “promote” must be interpreted in context. For example, Cockfield draws on judicial interpretations of “promote” in hate speech case law.98 But there, as here, a purposive analysis must be employed. Indeed, as Chief Justice Dickson explained in R v Keegstra: “[g]iven the purpose of the provision to criminalize the spreading of hatred in society, I find that the word ‘promotes’ indicates active support or instigation.”99 In stark contrast, the purpose of proactive regulatory compliance here demands a narrower purposive interpretation of “promote” to align that interpretation with the relevant context.

Having explained why “promote” warrants a narrow interpretation in the context of the SOP requirement, I now explain how licensees have extant equality promotion obligations in professional and general spaces.

1. Professional Obligation to Promote Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion

Lawyers are obligated to promote equality, diversity, and inclusion in their professional conduct, a point at least partially conceded by the Applicants.100 The relevant human rights instrument for Ontario lawyers is the Ontario Human Rights Code (the Code).101 It requires equality, diversity, and inclusion promotion. Specifically, the Code prohibits lawyers from discriminating based on protected grounds in their provision of legal services,102 in the preparation of a contract,103 and in their employment decisions104 (including harassment of employees).105 “Discrimination” prohibits action or inaction resulting in or failing to address formal or substantive inequality.106 In other words, non-discrimination obligations include duties that are both negative (i.e. an employer cannot sexually harass employees)107 and positive (i.e. an employer must, within reasonable bounds, promote an inclusive environment in their workplace).108 That Canada’s conception of equality is substantive rather than formal is clear, from the Supreme Court’s first equality decision,109 to its most recent.110 Demanding reasonable accommodation is not an unlawful positive obligation; rather, it is a recognized human rights duty cognizant of the inevitable substantive inequality that follows in its absence.

The Rules of Professional Conduct (Rules)111 — which prescribe lawyers’ ethical obligations in Ontario — similarly require the promotion of equality, diversity, and inclusion. The Rules are enacted under the Law Society Act, which requires the LSO to “maintain and advance the cause of justice and the rule of law,”112 ![]() Does not appear to be consistently adhered to or regulated in my read of how the LSO and lawyers operate, most terrifying, the LSO licensing known convicted pedophiles, judging them to be of good character, giving them easy access to and power over children. The SOP was nothing compared to being raped as a child.

Does not appear to be consistently adhered to or regulated in my read of how the LSO and lawyers operate, most terrifying, the LSO licensing known convicted pedophiles, judging them to be of good character, giving them easy access to and power over children. The SOP was nothing compared to being raped as a child.![]() “facilitate access to justice for the people of Ontario,”113 and “protect the public interest.”

“facilitate access to justice for the people of Ontario,”113 and “protect the public interest.”![]() I more often see lawyers rape the public interest than protect it. Murray Klippenstein quitting my case while not quitting others taken on years after taking on mine and chasing a COVID denier is a good example.

I more often see lawyers rape the public interest than protect it. Murray Klippenstein quitting my case while not quitting others taken on years after taking on mine and chasing a COVID denier is a good example.![]() 114 The Supreme Court has interpreted these provisions as prescribing an “overarching objective of protecting the public interest,”115 which can be promoted through means other than maintaining the competence of licensees.116 Indeed, “[a]s a public actor, the [LSO] has an overarching interest in protecting the values of equality and human rights in carrying out its functions.”117

114 The Supreme Court has interpreted these provisions as prescribing an “overarching objective of protecting the public interest,”115 which can be promoted through means other than maintaining the competence of licensees.116 Indeed, “[a]s a public actor, the [LSO] has an overarching interest in protecting the values of equality and human rights in carrying out its functions.”117

With this broad mandate, the LSO prescribes various rules for lawyers which pertain to promoting equality, diversity, and inclusion. In particular, the Rules — viewed in conjunction with their associated commentary — note that lawyers have special responsibilities by virtue of their privilege as a lawyer, including: (1) recognizing Ontario’s diversity and protecting the dignity of individuals;118 (2) honouring the obligation not to discriminate, including respecting the dignity and worth of all persons;119and (3) ensuring that service provision and employment practices comply with human rights obligations.120

Moreover, in Trinity Western, the Court held that it is open to the LSO to interpret “diversity within the legal profession” as serving “the public interest” and safeguarding the “public perception”121 of the administration of justice.122 Indeed, the Court expressly linked diversity, equality, and inclusion to the administration of justice: “[a]ccess to justice is facilitated where clients seeking legal services are able to access a legal profession that is reflective of a diverse population and responsive to its diverse needs.”123 Accordingly, there is clear precedent for interpreting the SOP’s equality promotion mandate as coming within the scope of the LSO’s statutory obligations. ![]() After watching the destruction of the SOP and the white male venom that oozed out of some of those destroying it and unbelievably voted onto the Board (proving to me how little some lawyers give a damn about others or the public interest), LSO has lost much credibility and is untrustworthy as a regulator (lawyers regulating lawyers just like the oil industry regulating itself, illegally frac’d aquifer after illegally frac’d aquifer).

After watching the destruction of the SOP and the white male venom that oozed out of some of those destroying it and unbelievably voted onto the Board (proving to me how little some lawyers give a damn about others or the public interest), LSO has lost much credibility and is untrustworthy as a regulator (lawyers regulating lawyers just like the oil industry regulating itself, illegally frac’d aquifer after illegally frac’d aquifer).![]()

Does complying with the many obligations described above promote equality, diversity, and inclusion in professional spaces? Undoubtedly, yes. The analytical flaw in SOP criticisms is that they invert the analysis. The SOP is not a free-standing obligation to promote equality in every fathomable way (from slam poetry to documentary film-making).124 Instead, the SOP requires that lawyers acknowledge their obligation to promote equality in the ways already required. To claim that there is no existing obligation to promote equality is to claim that abstaining from discrimination and harassment and failing to provide a reasonably inclusive workplace do not promote (i.e. support) diversity in the workplace. Clearly, they do. It follows that lawyers, contrary to the views of the Applicants, do have extant obligations to promote equality, diversity, and inclusion in their practice.125

2. General Obligation to Promote Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion

Lawyers are also obligated to promote equality, diversity, and inclusion in their general conduct. This is not totalitarian; rather, it is a consequence of the privileged position occupied by lawyers in society. Just as judges have special obligations in terms of partisan advocacy,126 lawyers have special obligations to the administration of justice. ![]() Really?

Really?![]() Specifically, while the Code only imposes human rights obligations in specific settings,127 the Rules extend to a lawyer’s “public life.”128 They require that lawyers “encourage public respect for and try to improve the administration of justice,”

Specifically, while the Code only imposes human rights obligations in specific settings,127 the Rules extend to a lawyer’s “public life.”128 They require that lawyers “encourage public respect for and try to improve the administration of justice,”![]() In my view, the SOP killers loudly pissed on the administration of justice. I see too many lawyers breaking the law, making shit up to get away with breaking the rules, misrepresenting their clients, violating client-solicitor privilege, knowingly putting innocent persons in prison, harming children and the public interest, proudly helping oil companies pollute and harm communities again down the street etc. etc. etc.

In my view, the SOP killers loudly pissed on the administration of justice. I see too many lawyers breaking the law, making shit up to get away with breaking the rules, misrepresenting their clients, violating client-solicitor privilege, knowingly putting innocent persons in prison, harming children and the public interest, proudly helping oil companies pollute and harm communities again down the street etc. etc. etc.![]() and the commentary notes that lawyers’ obligations in this regard are “not restricted to the lawyer’s professional activities but is a general responsibility resulting from the lawyer’s position in the community.”129 The commentary to the Rules notes that licensees are required — as individuals who wield power and privilege in society — to “encourage public respect for and try to improve the administration of justice.” The phrasing in the commentary is unambiguously positive. Accordingly, the positive nature of these obligations is not in question, only whether that obligation extends to the interests of “diversity”130 or “equality and human rights,”131 the promotion of which the Supreme Court of Canada has already confirmed improve the administration of justice. It follows that — in both professional and public settings — lawyers have equality promotion obligations, even if “the Rules are mainly [i.e. not exclusively] directed at regulating lawyer … conduct within law practice.”132

and the commentary notes that lawyers’ obligations in this regard are “not restricted to the lawyer’s professional activities but is a general responsibility resulting from the lawyer’s position in the community.”129 The commentary to the Rules notes that licensees are required — as individuals who wield power and privilege in society — to “encourage public respect for and try to improve the administration of justice.” The phrasing in the commentary is unambiguously positive. Accordingly, the positive nature of these obligations is not in question, only whether that obligation extends to the interests of “diversity”130 or “equality and human rights,”131 the promotion of which the Supreme Court of Canada has already confirmed improve the administration of justice. It follows that — in both professional and public settings — lawyers have equality promotion obligations, even if “the Rules are mainly [i.e. not exclusively] directed at regulating lawyer … conduct within law practice.”132

D. Conclusion: The SOP Is a Regulatory Reminder

The foregoing discussion clarifies the true nature of the SOP. It is not a “Loyalty Oath”133 enforced by the “thought police”;134 it is not a “quota”;135 it does not “mak[e] it harder for members of the public to identify impartial and independent-minded lawyers and judges”;136 or force lawyers to violate their ethical “duty of loyalty” to their clients;137 it does not mandate that Canadian law professors endorse current equality jurisprudence;138and it certainly does not “place[] vulnerable and marginalized people at risk.”139 Rather, the SOP is a modest step towards enhancing regulatory compliance.

It “calls on licensees to reflect on their professional context and on how they will uphold and observe human rights laws”140 to “ensure that licensees do not lose sight of regulatory obligations in the scramble of keeping a practice running.”141 In this sense, I agree with Cockfield regarding the intent of the SOP requirement to promote “reflect[ion] on racism within law practice.”142

By reminding lawyers of their professional and public obligations — but not creating novel obligations — the LSO seeks to combat systemic discrimination proactively,143 which existing instruments are already directed towards addressing reactively; “shift[ing] the focus from individuals to systems and from ad hoc human rights liability to the promotion of an inclusive and diverse professional culture.”144 A proactive approach is, indeed, particularly critical in the context of racial discrimination given how difficult it is to detect its “subtle” scent145 — a critical point for those who view the SOP requirement as an unnecessary redundancy.146 Indeed, as critical race theorist Alan Freeman instructs, “affirmative efforts” directed towards changing the “conditions” of systemic hierarchy are a necessary ingredient in combatting racial discrimination.147 In then Professor (now Justice) Woolley’s words:

Compliance-based regulation depends on regulated parties — and in particular on regulated entities — acknowledging regulatory obligations, creating strategies for accomplishing those obligations and reporting on the success of those strategies. Compliance-based regulation aims not to punish lawyers for doing things wrong, but to help lawyers create structures and strategies for getting it right. Doing that requires lawyers acknowledging what they need to do, creating strategies for doing it, and monitoring how those strategies work … It aims to achieve and support good practices, rather than occasionally and haphazardly punishing the bad.148

I acknowledge that the SOP is not immune to critique. One might criticize whether such acknowledgments are effective at improving compliance with regulatory obligations,149 whether they should target institutions rather than individuals,150 whether they should be optional,151 or whether they go far enough.152 One might also criticize the name of the requirement — Statement of Principles — which, I will readily concede, connotes aspects of speech (“statement”) and conscience (“principles”),153 although “Reminder of Regulatory Obligations” has less ring to it. One could doubt that anyone will actually reflect on their equality obligations,154 though there is anecdotal evidence to the contrary.155 Lastly, one might note that certain non-binding explanatory materials disseminated by the LSO — though not formally enacted by it — supported the Applicants’ interpretation of the SOP as violating freedom of conscience.156 Specifically, an earlier version of a “Key Concepts” document explained that the SOP’s intention “is to demonstrate a personal valuing of equality, diversity, and inclusion,”157 which would extend the SOP beyond a simple “reporting requirement.”158 However, that document was revised — wisely159 — and then simply provided what a statement of principles “may consist of.”160 Notably, none of these critiques establish that the SOP as enacted created new equality promotion obligations or violated free speech. Further, none of these critiques offer an alternative as to how to better promote pro-active compliance with human rights obligations.

III. CRITICAL ANALYSIS: LIBERTY VEILS AND EQUALITY TALES

Having clarified the SOP requirement’s modest imposition of annual self-directed journaling, I now take a theoretical detour from my doctrinal analysis to make a brief observation in the tradition of critical race theory. In my view, free speech is a “smokescreen”161 in this case — an example of what Patricia Williams describes as “power abuses that may lurk behind the ‘defense’ of free speech”162 (indeed, “liberty” claims are an age-old rhetorical technique to resist equality measures).163 Specifically, broader factual considerations — that some would consider irrelevant to the technical legal resolution of the SOP controversy — corroborate this perspective.164 There has been significant debate surrounding whether the SOP opponents are “good faith constitutional objectors.”165 Of course, I cannot divine whether each of the objectors is subjectively acting in good faith, and, following the wise words of W.E.B. Du Bois, do not want to “inveigh indiscriminately”166 against the mass of SOP opponents who, publicly or privately, range from apprehension to antipathy.

But the circumstances surrounding the SOP controversy strongly call into question the extent to which it is accurately characterized, on the whole, as a debate pertaining to free speech, not equality. Limited criticism has been levied at the more obtrusive Required Oath, which has existed for over a century,167 or the LSO’s other speech regulations, such as those pertaining to lawyer advertising.168

In comparison, the SOP has received significant and sustained resistance, including: (1) Bencher Troister’s motion seeking to vote on the SOP separately from the Working Group’s other recommendations,169 in part, because he considered the SOP problematic;170 (2) Bencher Groia’s motion seeking to permit conscientious objection to the requirement;171(3) multiple scathing critiques against the SOP requirement;172 (4) the Application seeking a declaration of the SOP’s unconstitutionality;173 (5) the creation of a StopSOP Bencher slate, dedicated to reversing the SOP requirement,1 74 which they consider “the most urgent issue facing the legal profession in Ontario”;175 and (6) the SOP requirement’s ultimate repeal.176 Of course, the incongruity between opposition against the Required Oath and the SOP requirement does not directly respond to any substantive concerns regarding the latter.177

But when a public state-drafted oath demanding that licensees “champion” (i.e. publicly and militantly support)178 the “rule of law” ![]() In my view of other cases and my own experiences trying to seek “justice” for harms done to me, my rights and water supply, and trying to get regulators to enforce the “rule of law” to reign in law-violating Encana/Ovintiv, that oath appears to be more about gagging harmed Canadians to protect the status quo (which includes white supremacy/privilege/colonial rape & pillage)

In my view of other cases and my own experiences trying to seek “justice” for harms done to me, my rights and water supply, and trying to get regulators to enforce the “rule of law” to reign in law-violating Encana/Ovintiv, that oath appears to be more about gagging harmed Canadians to protect the status quo (which includes white supremacy/privilege/colonial rape & pillage)![]() goes virtually unchallenged for over a century, and a private self-drafted journal entry alluding to “diversity” raises instant fury,179 it is suspect to claim that this controversy has nothing to do with diversity.

goes virtually unchallenged for over a century, and a private self-drafted journal entry alluding to “diversity” raises instant fury,179 it is suspect to claim that this controversy has nothing to do with diversity.

In fact, by the final stages of peer-review for this article, the anti-SOP benchers twice voted against making the SOP a voluntary requirement, instead seeking its outright repeal.180 Those benchers shifted from seeking to prevent compelled speech (which is satisfied by a voluntary SOP), to seeking to prevent “virtue signalling”181 and “political correctness”182 (only satisfied by a repealed SOP). It seems, therefore, that their opposition was not motivated by speech, but rather, diversity.

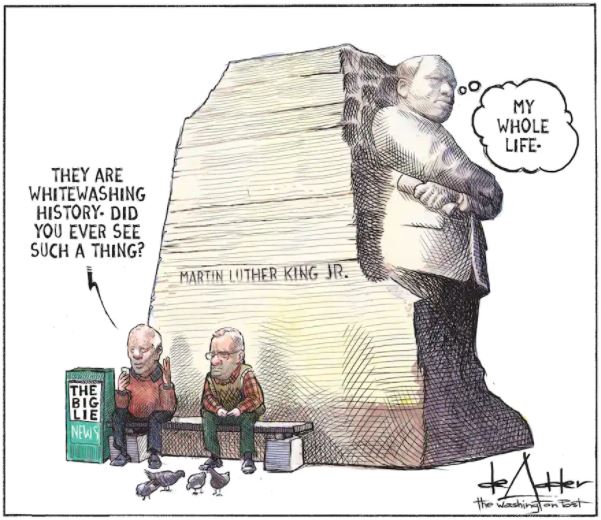

That this controversy is “pro speech in form, but anti-diversity in substance,”183 is corroborated by two further considerations: the demographics of the SOP debate, and many of its opponents’ openly admitted disdain for diversity.

The homogeneity of those who oppose the SOP requirement is anecdotally notable; they are predominantly — though not exclusively184 — white men.

And, as multiple racialized commentators have observed, such a demographic may “misunderstand the issues because they cannot see them from the perspective of minority lawyers”185and “may not experience the same kind of discrimination that some of us in the profession who are racialized … experience.”186 More perniciously, their motivation to deny the existence of systemic racism may be its corollary — that they, as white people, are unjustly enriched by the racial privileges systemic racism bestows on them (especially, perhaps, for “those individuals whose positive perceptions of themselves were more fragile”).187 Just as “[i]t is instructive that the chief proponents for sanctioning people who inflict [racist speech] injuries are women and people of colour,”188 it is instructive that the chief proponents of diversity in the legal profession are, similarly, women and people of colour.189 In my view, it is difficult — if not wilfully blind — to disregard the optics of this demographic divide, and to not interrogate whether the real target of this fury is diversity, not speech. In other words, the content, not compulsion,of the SOP is its real controversy.

But why speculate? Sure, overwhelmingly white resistance to the SOP and notably racialized support for it190 can support the inference that this controversy was triggered by disagreement over equality, not speech.

Thankfully, though, no such inference is needed in this case. Indeed, many SOP opponents have, by open admission, made their disdain for equality initiatives clear: that diversity is vacuous (“whatever that means”191); is a misguided trend (“faddish and jargonistic concepts”192 or “fashionable ideological causes”193); overlooks how racialized people are simply disinterested in the law (“[w]hat if there are many reasons why different groups of people [] choose different paths?”194); is a fiction predicated on the myth of “systemic racism”;195 and even is anti-Semitic (“the Law Society is telling us that there are, in effect, too many white Jewish lawyers”).196 Bencher Goldstein went even further, quoting — with admitted “common sense” approval197 — an online comment claiming that the underrepresentation of racial minorities in law is, in “large part,” credited to their lack of “a culture of learning” (a tweet he has since deleted).198

This admitted contempt for equality, diversity, and inclusion (or worse, this open admission of racist beliefs) in publications specifically directed towards resisting the SOP requirement illustrates that the real reason for the forceful opposition to the SOP is precisely the rationale for its impos-ition: insufficient awareness of systemic discrimination in Canadian legal practice, which, in turn, can meaningfully impair the profession’s ability to proactively redress that discrimination. The protest against the SOP, ironically, illustrates its importance.199 So what is the SOP controversy really about? It’s about a system of oppression that certain largely privileged licensees are unwilling to acknowledge, and who, through their rejection of that system, demonstrate its sustained force.

Footnote:

196 Klippenstein, supra note 6. See also Cockfield, “Lawyer Liberty”, supra note 19 at 15, n 45. On this point, I must address the perversion of “intersectionality” employed by certain SOP opponents. For example, Cockfield claims that the SOP requirement pays “a lack of attention to intersectionality” by disregarding how promoting racial diversity mandates exclusion of Jewish lawyers (Cockfield, “Lawyer Liberty”, supra note 19 at 16). I have three responses: (1) the SOP requirement is not a quota, it mandates nothing of the sort; (2) the SOP requirement merely acknowledges general human rights obligations, including those regarding the protection of religious minorities, and so only reinforces protections against anti-Semitism; and (3) this critique fundamentally misconstrues intersectionality. Intersectionality is a theoretical framing that unearths the “multidimensionality” of an individual’s experience, which is predicated on multiples axes of identity, in contrast “with the single-axis analysis that distorts these experiences”. See Kimberle Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics” (1989) U Chicago Legal F139 at 139. It follows that (a) supposedly overlooking Jewish lawyers is not an “intersectional” argument, it rests on one axis of identity, not multiple, and (b) the SOP is itself an inter-sectional instrument. Promoting mindfulness of how multiple axes of identity — e.g. race, gender, sexual orientation, and religion — suffer from systemic discrimination combats intersectional discrimination, rather than exacerbating it. If anyone overlooks intersectionality, it’s the SOP opponents that deny the existence of systemic discrimination itself, intersectional or otherwise.

End Footnote.

IV. CONSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS

The SOP requirement mandated that lawyers acknowledge their existing legal obligations, nothing more. While this rendered the Application largely moot — since the Application sought a declaration that “[t]he requirement shall not be interpreted as imposing any new obligation”200 — it was still open to the Applicants to argue that acknowledging extant obligations, in itself, coerces speech. In my view, however, Canadian constitutional law does not countenance such a trivial understanding of free expression. That said, I begin with brief remarks rejecting the claim that the SOP requirement violated freedom of conscience, followed by a more detailed analysis of why the SOP requirement failed to undermine Canada’s democratic commitment to free expression. With respect to both freedoms, I note at the outset that to the extent there was never any coercive mechanism in place to enforce compliance with the SOP requirement — abstainers simply received a reminder letter201 — one could question whether the SOP “requirement” actually compelled anything at all in terms of thought or speech. This calls into question whether any freedom was plausibly violated in these circumstances (or, at least, severely attenuates any constitutionally significant impact from the SOP’s imposition for purposes of justification under section 1).

A. The SOP Did Not Violate Freedom of Conscience

The Applicants alleged that the SOP requirement violated section 2(a) of the Charter.202 But such an infringement requires state action that impacts — or at least seeks to impact — one’s thoughts, beliefs, opinions, etc.203 To the extent the SOP incidentally grazed one’s thoughts, it did so in a constitutionally permissible manner.

First, the SOP requirement did not prescribe thoughts, beliefs, or opinions (which would constitute a clear violation of free conscience). As discussed above, the requirement simply required acknowledgement of extant obligations. Accordingly, the Applicants’ core freedom of conscience claim — that the SOP forced lawyers to “personally adopt … a particular set of values”204 — was predicated on a flawed interpretation of the SOP requirement.205 The constitutional scrutiny of government measures cannot hinge on the consequences that follow from a plaintiff ’s unreasonable misinterpretation of those measures.206 In this way, the SOP requirement bears no analogy to historical scenarios where, for example, prior expressions supportive of the Communist Party (or membership therein) were disqualifying for membership within the legal profession.207

Second, to the extent the SOP encouraged — but in no way required — lawyers to “take a moment and reflect”208 on human rights obligations, this is a trivial limitation on freedom of conscience. To be clear, I interpret the SOP as an exercise which, through optional “self-reflection,”209 gestures towards greater compliance with human rights obligations. This undoubtedly implicates thought insofar as it involves lawyers thinking about their human rights obligations. But (modestly) enforced reflection is not policed thought.210 Moreover, states ubiquitously encourage thinking about compliance with established law, without actually “regulating”211 one’s thoughts. In fact, the state can constitutionally use means far more severe than the SOP requirement to encourage lawful behaviour. For example, the Canadian Criminal Code permits the imposition of sentences that “deter the offender and other persons from committing offences.”212 Do criminal sentences infringe free conscience by seeking to deter offenders not only from committing crimes, but from wanting to commit crimes? This is where the Applicants’ logic takes us.213

If promoting a favourable outlook on lawful conduct through sentencing considerations does not violate freedom of conscience, then, in my view, the SOP requirement can hardly be said to do so. Put differently, if it is appropriate for the state to promote compliance with criminal law through incarceration, it is appropriate for the state to promote compliance with human rights law through administration. A criminal sentence undoubtedly constitutes graver encouragement than a reminder letter. And the pressure exerted by the SOP requirement — as it stands, the “tyranny”214 of snail mail from the LSO — pales in comparison to the undisputed legal and financial consequences of failing to meet one’s human rights obligations. This point cannot be overstated. Cockfield, for example, argues that the SOP requirement violates free thought by pointing to Bencher Anand’s description of its end goal of “culture change.”215 But the end goal of legal compliance with human rights obligations (what “culture change” means in this context) is an intrinsic objective in any functioning legal system.

It is critical, therefore, to comprehend the scope of a finding that the state encouraging compliance with existing law violates freedom of conscience. Laws, inherently, encourage compliance; their violation triggers sanctions. If freedom of conscience extends from the freedom to hold any beliefs, to the freedom to never experience pressure — no matter how slight — against certain actions, and in turn, pressure against wanting to commit those actions (the only point at which free conscience is implicated here), the state will cease to function. To be clear, I am not endorsing laws which mandate agreement with existing laws. Clearly such laws would violate freedom of conscience, and would be antithetical to democracy and the dialectical negotiation of our laws.216 Rather, I am endorsing the existence of a legal system which, by its very nature, encourages compliance with that system and, indirectly, a desire — in one’s conscience — to so comply. That is all the SOP requirement does: not mandate agreement with human rights obligations, but proactively promote compliance with them.

Alternatively, Leonid Sirota alleges that the violation of free conscience in this case follows from the fact that “promoting values requires [one] to hold them.”217 However, this argument — which is predicated on the SOP requirement requiring that all licensees proselytize diversity — has already been rejected above. And since this argument is based on an unreasonable misunderstanding of the SOP requirement, it is constitutionally irrelevant.218

B. The SOP Did Not Violate Freedom of Expression

The Applicants claimed that the SOP requirement violated section 2(b) of the Charter. In their words, it was coerced speech “alien to Canada’s political traditions and the traditions of all free states”219 that would have a “chilling effect” on free expression.220 The Applicants went so far as to claim that they “will be forced to cease practicing law.”221 Indeed, one Applicant now claims that opposing the SOP requirement has already “destroy[ed] the career and law firm [he] had built.”222

The SOP requirement does not violate free expression. I will explain why in three steps: (1) outlining the purposes underlying constitutional protection of “free expression”; (2) distilling the leading test from Irwin Toy (speech generally) and Lavigne (compelled speech); and (3) applying that test to the SOP requirement.

1. The Purposive Scope of Free Expression

Any discussion of free expression must start from the premise that we are not actually “free” to express ourselves however we wish. For example, there is relatively limited opposition to the following general expression limitations: defamation;223 perjury;224 fraud;225 bribery;226 yelling “fire” in a crowded theatre;227 intellectual property (e.g. copyright and trademarks);228 staging a rock concert at 2:00 am;229 unregulated parades,230 lobbying,231 advertising,232 media,233 broadcasting,234 campaign financing,235 and campaign literature;236 speeding in a car to express masculinity;237 influencing active jurors;238 page limits on court filings;239 publishing the biographical details of sexual assault victims;240 publishing classified information;241 violently threatening people;242 and directly inciting violence.243 And some of these examples are not even conceived of as limits on free expression under section 1 of the Charter. Rather, they are understood as forms of expression beyond the scope of constitutional protection, since an absolutist position of free expression is “obviously untenable.”244

It follows that, before we critique the SOP requirement, we must appreciate what “free expression” actually entails in a democratic context. Clearly, the many examples above are forms of expression (i.e. ways of conveying meaning).245 It is clear, therefore, that constitutional free expression cannot be defined colloquially,246 but instead must be defined purposively.247 By this, I mean that any workable understanding of free expression must take meaning from the democratic purposes it serves.248 Simply put, “freedom of expression is primarily a process … for reaching other goals.”249 And, more specifically, its “root purpose” is “to assure an effective system of freedom of expression in a democratic society.”250 Only with this democratic framing in mind can we conduct a proper free expression analysis. That the statement of principles involves a statement, therefore, is only the tip of the free expression iceberg; and SOP opponents whose analysis boils down to the SOP requirement involving a compelled statement, thus, paint an incomplete constitutional picture.

The purposes underlying the protection of free expression can be grouped into four broad categories:251 (1) individual self-fulfilment (i.e. free expression is good for individuals because it facilitates their development of ideas, mental exploration, and self-affirmation252); (2) pursuit of truth (i.e.free expression is good for society because dialectic processes optimize knowledge advancement and truth discovery, even with ‘bad’ ideas, since they compel “rethinking and retesting” accepted truths253); (3) participation in social and political decision-making (i.e. free expression empowers all members in society — whether elite or marginalized — to participate in the building of our culture, and in turn, in holding the state accountable to democratic will254); and (4) maintenance of the balance between stability and change in society (i.e. free expression is good because it strikes a better balance than censorship between “healthy cleavage and necessary consensus”255 by promoting authentic cohesion rather than “superficial conformity”256). These are the purposes served by maintaining a viable system of free expression.257 With all these laudable purposes in mind, I echo those who criticize the SOP requirement insofar as they affirm the critical importance of free speech to a liberal and democratic society. Absent a purposive framing, we devalue free expression. Freedom of expression holds fundamental importance in our society258 — some even consider it the most important right in our society259 — precisely because of the critical purposes it serves. That fundamental importance is trivialized by the claim that any “expression,” no matter how remote its relationship to these purposes, ought to be protected.260 For example, one could not credibly argue that aimlessly screaming in a residential neighbourhood at 4:00am deserves constitutional protection. Such an example is precisely what Peter Hogg describes as “behaviour that is outside the purpose [of the right] and unworthy of constitutional protection.”261 Furthermore, purposive framing clarifies “the governing principle of the Supreme Court of Canada’s definition of expression”:262 content neutrality.263 Indeed, without content neutrality, many of the purposes listed above would be undermined. In this case, content neutrality means that our assessment of the SOP requirement cannot turn on our endorsement — or rejection — of the human rights status quo to which that requirement relates. With this in mind, a Rawlsian approach is instructive.264 As I explained above, the SOP requirement simply mandates that all licensees acknowledge their extant professional and human rights obligations. Currently, those obligations include duties to not perpetuate adverse effects discrimination — a laudable objective, in my view (and in the view of many progressive human rights thinkers). But, in the interest of content neutrality, let’s assume that future Canadian jurisprudence pivoted regressively by following the American model that holds, for example, that discrimination must be intentional to be actionable under the Equal Protection clause.265 In turn, the SOP requirement would no longer mandate acknowledgement of obligations with respect to adverse effects discrimination, but instead, to intentional discrimination only. Many progressive scholars may oppose such a narrow acknowledgment; just as certain conservative thinkers oppose the positive obligations recognized by contemporary equality jurisprudence. That said, the question with respect to free speech (a putatively content neutral exercise) remains the same in either scenario: whether a state-mandated acknowledgment of status quo obligations — whatever those may be — amounts to unconstitutional compelled speech. Following this logic, the constitutionality of the SOP requirement is doctrinally coterminous with the constitutionality of a requirement that lawyers acknowledge their “mortgage fraud avoidance obligations.”266 I will now explain why, no matter the obligation at issue, acknowledging their existence does not violate free expression.

2. The Governing Test for Free Expression

Section 2(b) guarantees “freedom of … expression” to “everyone.”267 I will navigate the leading decisions — principally, Irwin Toy (the general test) and Lavigne (the test for compelled speech) — to distill the test that governs here. I will then apply that governing test to the SOP requirement.

a. General Expression Test (Irwin Toy)

Irwin Toy is the germinal free expression decision,268 and in Ontario — the jurisdiction of the SOP litigation — it remains the leading precedent.269 In Irwin Toy, the Court unanimously held that certain prohibitions against television advertising directed at children violated free expression.270 The dissent abstained from articulating the scope of section 2(b), since it considered the violation in that case “evident.”271 In contrast, the majority laid out a detailed test. It provides what I would describe as a two-step engagement/control test, best understood as a series of rules and exceptions delineating the protective scope of section 2(b).272 I describe that test below, with qualifications and clarifications emanating from the Court’s subsequent jurisprudence.

It is helpful to have a bird’s eye view of the test’s operation. To violate free expression, a state measure must engage protected speech (Step 1) and control that speech either in purpose (Step 2(a)), or effect (Step 2(b)). There is no requirement that Steps 2(a) and 2(b) both be met for a free speech violation.273

I will call Step 1 “engagement.” The Majority describes this step as an inquiry into whether the plaintiff ’s activity was within the sphere of conduct protected by freedom of expression, but I prefer engagement as an abbreviation. Engagement involves a rule (content) and an exception (form).2 74 I will address each in turn. If Step 1 is met — i.e. if free expression is engaged — I will call the activity “protected speech.” Only protected speech proceeds to Step 2 of the analysis. In contrast, the state is free to limit unprotected speech without restraint from free speech protections under the Charter.

The rule for engagement — expressive content — is that free expression is engaged whenever the plaintiff ’s activity attempts to convey meaning.275 For example, parking a car per se does not engage free expression, whereas parking a car illegally to protest parking regulations would.276 To be clear, the relevant speaker is the plaintiff, not anyone else. Thus, when a union expends money on its activities, the plaintiff contributors do not “attempt to convey meaning” through dues they “either willingly or unwillingly contribute.”277 This is because “reasonable people” would not hold all contributors “responsible” for the positions taken by those contributors’ union.278 Whether an impugned statement or activity conveys meaning is content neutral, i.e. it is constitutionally scrutinized for its existence, not its quality.279 This protects all speech, no matter how nefarious.280 That said, trivial meanings do not engage section 2(b). Paying union dues, for example, conveys compliance with one’s collective bargaining agreement. But that does not bring such mandatory payments within the protective scope of free expression.281 The exception for engagement — impermissible form — is that even if the plaintiff ’s activity attempts to convey meaning, that activity will still be excluded from constitutional protection if it takes on an impermissible form.282 The Court does not exhaust the list of impermissible forms, but describes “violence” as a “clear” example on the list, and leaves the door open to other impermissible forms.283 This exception excludes other trivial claims, such as claiming that murder (conveying hatred) or rape (conveying dominance) are constitutionally protected free expression.284 It has also excluded threats of violence285 and harassment286 from constitutionally protected expression. The Court has even held that “keeping a common bawdy house” is an unprotected form of free expression,287 though it did so in “very short shrift.”288 The Court has yet to describe the “precise ambit” of the impermissible form exception.289 However, it has explained that any impermissible “form” of expression cannot be defined by the “content” of its message e.g. hate speech.290

I will call Step 2 “control.” It concerns “whether the purpose or effect of the impugned governmental action was to control” protected speech.291 It therefore contains two sub-steps: Step 2(a) (purpose) and Step 2(b) (effect).

Step 2(a) — purpose — involves a rule (expressive purpose) and exception (physical purpose). I will, again, address each in turn. Step 2(a) concerns the state’s purpose; it seeks to ascertain the “mischief ” targeted by the state’s measure.292 If the state’s purpose is invalid then it violates free expression, and the analysis proceeds to justification under section 1 of the Charter,293 without consideration of the law’s effects. In contrast, if the state’s purpose is valid, then it does not yet violate free expression, and the law’s incidental effects are then constitutionally scrutinized (per Step 2(b)).294

The rule — expressive purpose — is that if the purpose of the state’s measure is to control protected speech, then that purpose is invalid.295 That purpose, though, must be carefully identified: an overly objective test (i.e. whether expression is factually controlled) is over inclusive, whereas an overly subjective test (i.e. whether the government admits it sought to control expression) is under inclusive.296 There is “inherent difficulty” in labelling any given limitation of expression as being directed towards controlling expression per se.297 This is because “[e]xpression in itself is not normally harmful, and the objective of the limitation is not normally to suppress the communication as such” but rather “to forestall some anticipated effect of expression.”298 Similarly, as Elena Kagan remarks: “it is difficult to see why anyone would opt to regulate a viewpoint that did not cause what seemed (to the regulators at least) to be a harm — or at a bare minimum, that could not reasonably be described as harmful.”299 Indeed, most speech limits have an intermediate purpose (limiting speech) and an ultimate purpose (preventing the consequences of that speech), such that the state’s ultimate purpose will rarely target speech itself: either robbing Step 2(a) of any protective force (if the Court happens to select the ultimate purpose);300 or, alternatively, guaranteeing an invalid purpose (if the Court happens to select the intermediate purpose).301 Despite these concerns, the Court’s approach in Irwin Toy strives to identify state limitations with the purpose of limiting free expression.302

The exception — physical purpose — is that even if the state seeks to limit free expression, that purpose remains constitutionally sound if the measure is a good faith restriction on protected speech with direct physical consequences303 (e.g. littering).304

Lastly, Step 2(b) — effect — similarly involves a rule (factual effect) and exception (purposive effect).305 As this step is only reached if the state’s purpose is not to control protected speech, this step concerns the incidental effects of state limits, not their purposeful effects (which violate free expression earlier in the test under Step 2(a)).306

The rule — factual effect — is that if the state’s measure has the incidental effect of controlling protected speech, it has an unconstitutional effect.307 The threshold of such control is uncertain. Clearly, not any control qualifies as a factual effect. For example, paying taxes limits everyone’s available resources for speech — and compels everyone to financially support various state initiatives they may oppose308 — but would not be construed as a limit on free expression resulting in a factual effect.309

Jurisprudentially, it would appear that a plaintiff ’s “capacity to express his views” must be “impaired” for a factual effect to be made out.310 At a minimum, a “chilling effect” on expression — which, one would think, falls below overt censorship — appears sufficient to meet the factual effect threshold.311 What is clear, though, is that the origin of the impugned effect must be the state measure itself, not an unreasonable misunderstanding of that measure. So, for example, an anti-terrorism law that sanctions expression relating to ideologically-motivated violence — but not relating to ideology per se — cannot chill ideological expression, because that chill would only follow from an unreasonable misunderstanding of the law’s scope.312

The exception — purposive effect — is that even if the state’s measure incidentally controls protected speech, that measure remains constitutionally sound if the protected speech in question fails to serve “at least one of ” the purposes underlying the importance of free expression (e.g. truth, participation, and self-fulfillment).313 Specifically, the plaintiff must “at least identify” the meaning of their protected speech and how it relates to the purposes underlying free expression.314 This ensures that “unintended effects do not receive constitutional protection unless they strike at the heart of section 2(b).”315

b. Compelled Expression Test (Lavigne)