Are Albertans getting “timely” access to the courts or justice in civil cases? Are Charter rights of Albertans being violated by the delays in Alberta courts?

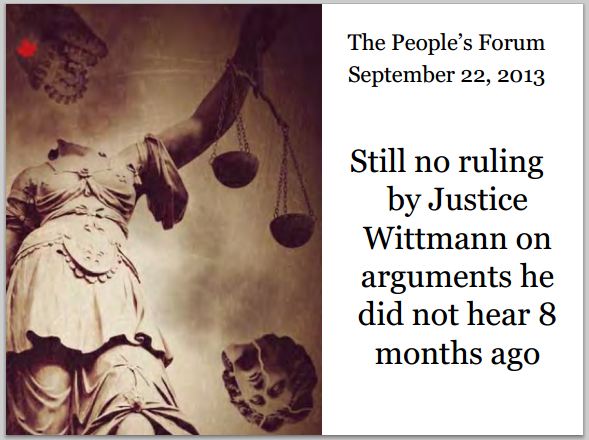

What about “timely” access to justice for Ernst’s civil case against the Alberta Energy Regulator for violating her Charter rights in the first place (for daring to ask questions about Encana’s endless non-compliances that began in 2003 and continue enabled by the regulator)?

Tories appoint 43 judges in June, filling long-standing vacancies by Sean Fine, July 7, 2015, The Globe and Mail

The Conservative government appointed 43 judges in June, filling appeal court vacancies left to languish as long as a year and a half and ending a shortage that contributed to backlogs in family, civil and criminal courts.

… The flood of appointments reduces the number of vacancies to 14. During the almost 10 years the Conservative government has been in power, judicial vacancies have often been at record levels, usually hovering around 50, according to figures from the Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs Canada.

On Manitoba’s highest court, the Court of Appeal, one job was left open since Jan. 1 of last year and another unfilled since the following May; both those posts were filled in June. A Quebec Court of Appeal position had been open since Nov. 1. And Ontario had more than 20 vacancies at one point.

The Conservatives also left the Supreme Court short one judge for an unprecedented 10 months and did not fill the job of Ontario chief justice for six months.

As a result, some courts have struggled to meet the demand for access to justice. In Quebec, civil trials expected to take longer than 25 days must be booked four years in advance, [HOW MANY YEARS IN ADVANCE MUST THEY BE BOOKED IN ALBERTA?] Superior Court Chief Justice François Rolland said in his annual public address last September.

After complaining that one of the vacancies on his court went back a year and another four positions had been open for six months, he jokingly asked if anyone could get Justice Minister Peter MacKay on the phone, because he had tried and failed. [How quickly does Mr Mackay return ERCB/AER/Encana/Cenovus/CAPP calls?] He has since retired.

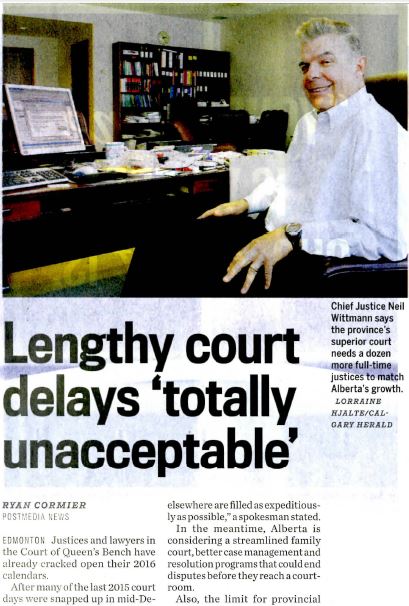

“The vacancies that sit there represent a judge that could be and should be available to the public,” said Michele Hollins, president of the Canadian Bar Association, adding that the CBA had repeatedly urged the government to fill the jobs. In her home province of Alberta, the shortage of judges has led to serious delays in family, civil and criminal cases, she said.

The Justice Minister’s office did not respond directly when asked why it had decided now to fill jobs left open for so long. Clarissa Lamb, a spokesperson for Mr. MacKay, said in an e-mail: “Judges are appointed based on merit and legal excellence and on recommendations made by the 17 judicial advisory committees across Canada. We work with our provincial counterparts to ensure they have the resources they need to administer the justice system more efficiently and effectively for Canadians.”

Leaving the judiciary with chronically high numbers of unfilled jobs is just one aspect of this government’s troubled relationship with the courts.

… The government has seen judges strike down its crime laws or make refugee rulings it disliked, and cabinet ministers have responded at times with vociferous public criticism.

Judicial appointments are a big part of Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s legacy, according to Wayne MacKay of the Schulich School of Law at Halifax’s Dalhousie University. The federal government appoints judges to provincial superior and appeal courts, the Federal Court and the Tax Court, as well as the Supreme Court. “He’s had more impact [than at the Supreme Court] installing judges with a small-c conservative, more restrained judicial temperament he’s looking for – one that’s more supportive of the government and less inclined to take an activist view of the Charter of Rights,” [Or trying to find justices less included to uphold the Charter and meet the Harper/Oil industry government’s need to destroy our Charter rights so as to cheaply frac us all?] Prof. MacKay said in an interview. [Emphasis added]

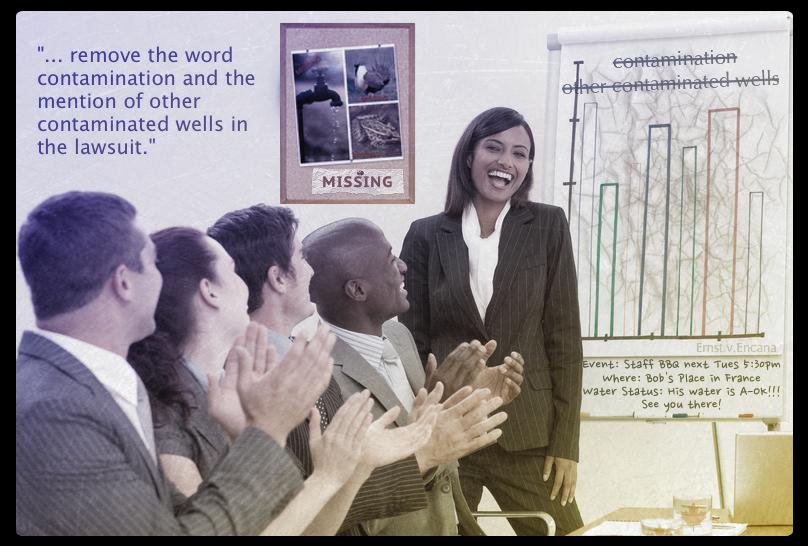

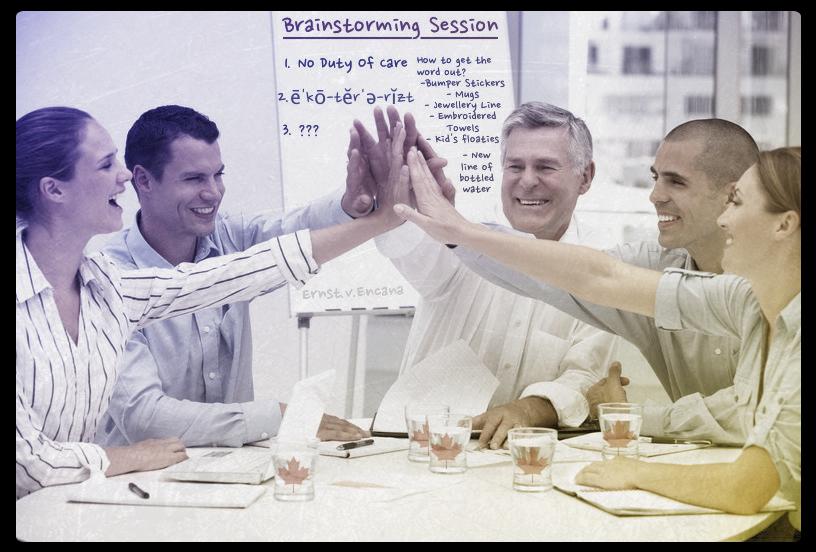

Slide from Ernst presentations

How long is too long? When justice delayed is justice denied by Georgia Harley, March 25, 2015, The World Bank

As the saying goes, ‘justice delayed is justice denied.’ Yet, across the world, court users complain that the courts take too long. For your regular court user facing endless talk from lawyers, reams of paper, and mounting legal bills, a court case can feel like it goes on…FOR….EV….ER.

But how long is too long? The question has arisen on each of my last four missions in as many months – from Kenya to Croatia to Serbia and back. And it’s not a rhetorical question. Answers can assist client countries in analyzing their efficiency and devising reforms that improve both timeliness and user satisfaction. It also enables potential court users to better estimate how long it might take to resolve their dispute – allowing them to then adjust their expectations accordingly.

After all, better enabling people and businesses to resolve their disputes contributes to poverty reduction and shared prosperity. [Ernst’s corporation is already destroyed by the Ernst vs Encana lawsuit, with Ernst living with Encana’s incessant noise and without safe water for over a decade.]

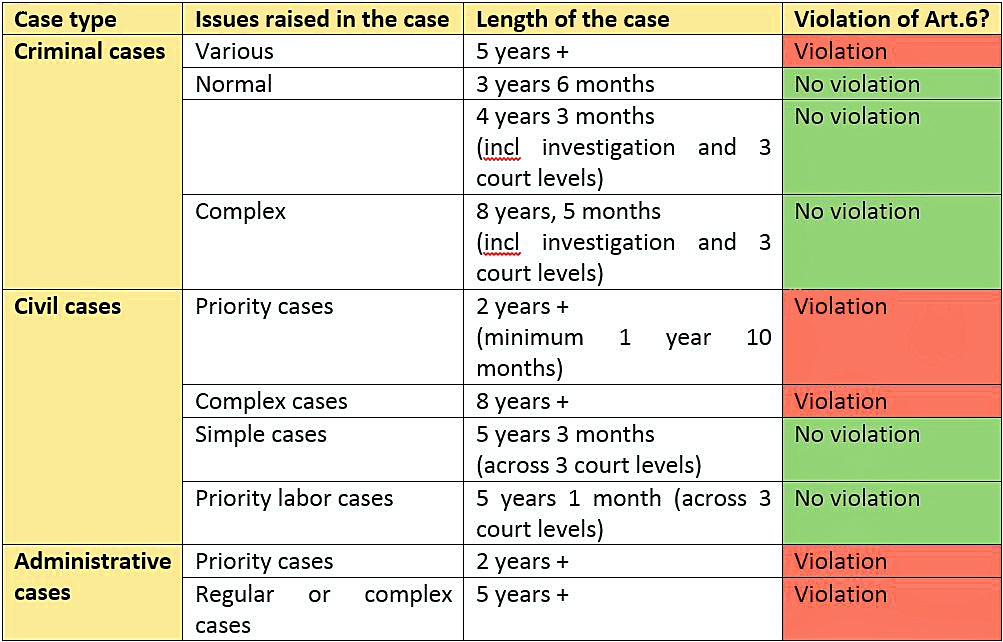

In an attempt to respond beyond rhetoric, I dusted off this old report by European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ). … The report analyzed a large number of decisions that had come before the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and provided insights into what that the Court considers an ‘unreasonable time’ to be. (The ECHR interprets Article 6 of its Convention, which requires all 47 Council of Europe States to ensure within their jurisdictions that ‘everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time’.)

… Despite what many people assume, there is no single international rule on how long cases should take. Each case must be considered on its own merits, but the following general ‘rules of thumb’ may be helpful.

In normal (not complex) cases, the ECHR generally considers two years to be reasonable. Beyond a duration of two years per court level, the European Court examines the case closely to see if the national authorities exercised due diligence in the process.

In priority cases, the ECHR may find a violation even if the case lasted less than two years. ‘Priority cases’ comprise cases that require quick resolution to be effective, such as labor disputes involving dismissals or unpaid wages, restraint of trade, compensation for victims of accidents, police violence cases, cases where applicant is elderly or their health is critical, and cases related to relations between children and parents. [What about cases involving companies illegally fracturing and contaminating a community’s drinking water supply and the “regulator” violating a citizen’s constitutional rights and slandering that citizen in a legal filing instead of “regulating” the law-violating company?]

In complex cases, the ECHR may consider a longer time to be reasonable. But in those cases, the Court tends to pay close attention to periods of inactivity to see if there were excessive delays.

Rarely has the ECHR considered more than 5 years to be reasonable. Never has it considered more than 8 years reasonable. The only times the Court did not find a violation in old (+5 years) cases were when the party’s own behavior contributed to the delay.

Some courts have developed their own working definitions of ‘old’ or ‘delayed’ cases. In Kenya, any case is considered ‘backlogged’ if it’s older than 1 year. In Serbia, it’s 2 years. In Croatia, it’s 3.

… After all, an average person might reasonably expect their simple traffic case to be resolved in a shorter time – say 6 months. And two corporate titans in complex civil litigation might reasonably expect their duel to last more than 2 years. [Would corporate titans accept the delays in the Ernst case?]

The report provides a summary table of cases decided by the ECHR by case type. Of course, these are not timelines countries should aim at – countries can and should do better. But they provide some insight for when ‘justice delayed’ may be ‘justice denied’ and becomes a breach.

[The Ernst versus Encana case is into its 8th year]

For some recent and applied examples of the Bank’s support to client countries in their efforts to understand and reduce court delays, check out the Serbia Judicial Functional Review and the Kenya National Case Audit and Institutional Capacity Survey.

[Refer also to:

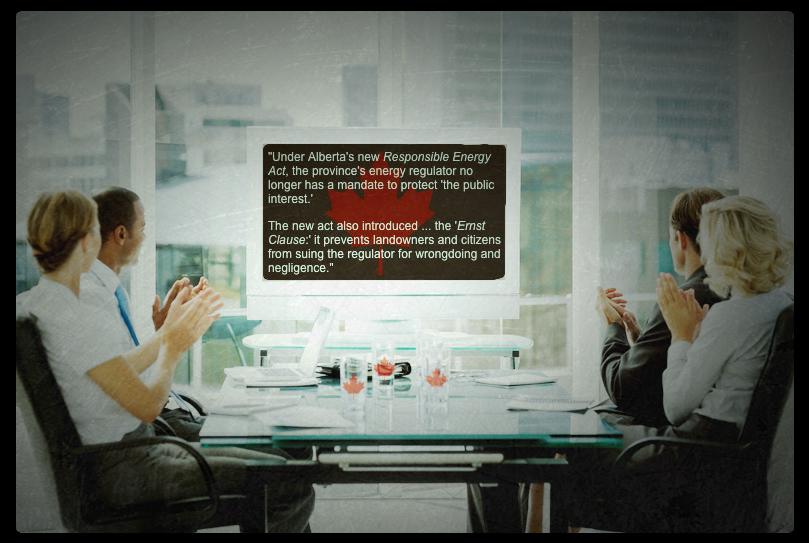

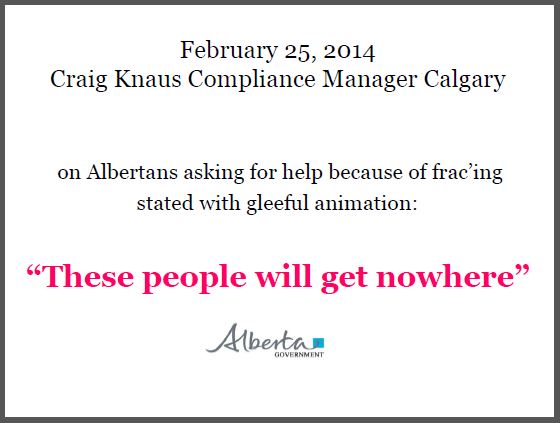

Images from FrackingCanada The Ernst Clause

Slide from Ernst presentations