Game Changer: The Beaver Lake Cree have gone to court to challenge the oilsands development. What if they win? by Arno Kopecky, June 2014, Alberta Views

“The Plaintiffs claim that under Treaty 6, the Crown has an obligation to manage the cumulative effects of developments.” —Lameman v. Alberta, 2011 ABQB 40

…

On the cold, clear February day that I made the drive to Anzac, a mellow hamlet of fewer than 1,000 people, I was kindly refused a glass of water at the fast food joint because of “seepage.” The water supply had been contaminated by industrial chemicals, the waitress explained; no one knew from exactly where, they just knew not to drink from the tap.

…

In 2008 the Beaver Lake Cree’s chief councillor, Alphonse Lameman, filed a court action against the governments of Canada and Alberta, alleging that the cumulative effects of industrial development were infringing on his people’s right to hunt and fish. “The animals are starting to deplete,” he told reporters on the day he launched his case. The lawsuit encompasses 321 “projects” with over 19,000 individual “developments”—everything from wellheads and pipelines to the Cold Lake air weapons range—but no single company is being sued. Instead, Lameman asked the court to hold the Crown responsible for industry’s collective environmental impact.

…

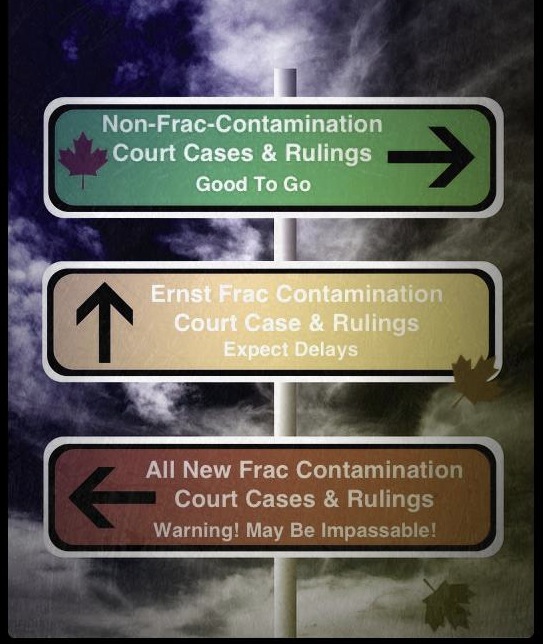

Canada and Alberta were listed as separate defendants in the Lameman action, and both sought to have the case dismissed. To appreciate the spirit of their approach, consider that one argument Canada advanced was that it was Alberta that issued industrial permits in the oil sands and therefore the federal government should not be held accountable; meanwhile, Alberta argued that treaty rights were a federal matter and therefore not the province’s responsibility. Such Catch-22s dragged on for five years, and it was only thanks to the

financial intervention of outsiders that the plaintiffs managed to hold on until April of 2013, when Alberta’s Court of Appeal finally ruled that the case deserved to be heard on its own merits and ordered everyone to get ready for trial. One year later the parties are still in case management, with no start date set for the trial as of this writing.

“It’s a white man’s legal system,” Susan Smitten, executive director of a non-profit called RAVEN, which raised $950,000 for Beaver Lake, told me. “It’s so stacked against First Nations on so many levels.” [And just as stacked against white men and women, notably so if lawsuits are in the public interest ]

[Refer also to:

Source: FrackingCanada