Ecological Overshoot Speaker Series Part 1: Dr. Bill Rees by blueislandgirl, Nov 14, 2023

Dr. Rees introduces the concepts of Earth’s carrying capacity and ecological overshoot, and the many environmental problems that are symptoms of this overshoot. We humans tend to fixate on a few major problems (war, pandemic, climate change) and have a difficult time connecting the dots—that is, thinking systemically. Bill talks about the implications of our failure to think systemically, and what it means for the future of our communities and for life on Earth.

Dr. William E. Rees is a population ecologist, ecological economist, Professor Emeritus and former Director of the University of British Columbia’s School of Community and Regional Planning in Vancouver, Canada. He is also a founding member and former President of the Canadian Society for Ecological Economics; a founding Director of the OneEarth Living Initiative; a Fellow of the Post-Carbon Institute and an Associate Fellow of the Great Transition Initiative.

***

We’re in a Behavioral Sink. It’s Why Everyone Acts So Mean All The Time by Jessica Wildfire, 22 Nov 2023, OK Doomer

A father refuses to bring his sick daughter a glass of water. He says, “I can’t wait on you. Just stop it, okay? Just stop.”

In another part of the country, a former adviser with Obama’s National Security Council harasses a food cart vendor. Finally, he says, “If we killed 4,000 Palestinian kids, it wasn’t enough.”

He doesn’t say it in anger.

He’s smiling.

Someone with a cross for a profile pic brags about trolling essential workers with masks. “When I’m shopping and the cashier is wearing one, I keep saying I can’t understand you until they lower their mask.”

Pastors like Rusell Moore warn the world that their congregations are rejecting the teachings of Christ. They’re not even trying to hide it anymore. You read from the Sermon on the Mount, about the importance of forgiveness and mercy. Evangelicals respond with, “Where did you get those liberal talking points?” They say, “That doesn’t work anymore.”

“That’s weak.”

Do you remember last year’s egg shortage? It wasn’t just bird flu. It was a verified collusive scheme to boost profits. A federal jury found the country’s two largest egg producers have a history of deliberately engineering scarcity. Once again, CEOs had no problem creating problems to generate wealth. They didn’t care what happened to anyone else. These are people we hold up as exemplars of success. We can only guess what they’ll try in the event of widespread crop failures.

Everywhere you go, you see behavior that’s outright malicious or wrapped in a thin veneer of politeness. You see it across the political spectrum.

What’s going on?

Let’s take a field trip. Here’s something you probably don’t learn in school about Constantine, the first Christian emperor of Rome. He killed his own son, Crispus. And his wife.

He did it for a few different reasons. First, Crispus posed a threat. He excelled as a military commander. He was popular. When Constantine heard a rumor that his son tried to rape his second wife and was plotting to overthrow him, he had him executed. Constantine was wrong. When he found out his wife had been lying to him the whole time, he threw her into a boiling bathtub. So, you could say that western leaders never really had it together.

Constantine is regarded as something of a hero by Christians.

He wasn’t.

In his own special way, he set Europe on the path to the dark ages. Not only did he make Christianity the official state religion, he started regulating and banning other religions.

Before Constantine, Romans practiced syncretism.

They blended religions.

Not anymore.

Now think about the story of Hypatia, about a century later. She was a popular philosopher and teacher in Alexandria. It was rare for a woman to command intellectual respect in 4th-century Rome, but she did. She became an advisor to the prefect. She practiced tolerance toward early Christians, even when extremist monks formed militias and started destroying libraries and pagan temples, melting down statues for gold. Because she taught classical philosophy, she was branded a pagan regardless of her own diverse spiritual beliefs.

The monks had a special name for Hypatia.

They called her a witch.

Finally, they dragged her through the city, ripped off her clothes, flayed her, and then dismembered her.

It’s a rough way to go.

Historians consider Hypatia’s death a symbolic transition to the dark ages. That’s a dramatic term for something a psychologist named John B. Calhoun called a behavioral sink, more than a thousand years later.

In the 1950s, Calhoun started building utopias for rats at Johns Hopkins University. He gave the rats everything they needed to live in peace and harmony. He gave them food and shelter. He gave them plenty of space, just not endless space. Then he sat back and watched.

He wanted to see what they’d do.

They didn’t disappoint.

Even in utopias that could theoretically support thousands of rats, the population stabilized around a few hundred. Rats organized themselves into groups of 12. That was their limit for living together. Not every species of rodent curbed their population growth to achieve homeostasis, but none of them ever reached the actual carrying capacity of their utopias.

Utopia 25 (with mice) was the biggest failure.

They overcrowded each other on purpose. They fought over resources when they didn’t have to. It didn’t matter how much food they had. It didn’t matter how many mating partners they had. It didn’t matter how many tunnels or nests they had. It didn’t matter how sanitary Calhoun made it. The mice reached some kind of psychological tipping point, and they went nuts. They killed each other. When violence broke out, the female mice ran away from the males. They started hiding. Social bonds fell apart. Mice became withdrawn. They stopped grooming themselves. Some chose to starve.

Mothers started attacking their own children and kicked them out of their nests before they were old enough to survive on their own. The mere presence of a male triggered violent behavior.

The population crashed.

It never recovered.

Only a handful of mice survived. They did it by abandoning society and living on the remote edges of the utopia. They didn’t do much. They slept, ate, and groomed. They wandered the periphery, keeping their distance.

Calhoun called them the beautiful ones.

These experiments influenced Edward T. Hall, a cultural anthropologist who taught at a number of universities, including Harvard and Northwestern. In the 1960s, he came up with a set of theories known as proxemics. Basically, it’s the idea that humans have boundaries for personal, social, and public space. If you violate those boundaries, people start to act… weird.

We need more than just food, water, and shelter.

We need psychological breathing room.

We have a lot in common with mice and rats, right down to our biochemistry and genetic makeup. That’s why labs use mice and rats to test products and treatments. We share a common ancestor that lived with the dinosaurs.

So when you ask what’s going on with humans and why we’re so mean to each other now, there’s one good answer.

We’re in a behavioral sink.

More and more humans enjoy dealing out cruelty to each other. They brag about it. They confidently reject the teachings of the religion they claim to uphold. They won’t bring their daughter a glass of water.

There’s even more going on.

Over the last hundred years, a handful of greedy sociopaths have conditioned us to celebrate selfishness and endless consumption. They’ve maximized our desires while depleting our resources. They’ve created conditions that make it hard or even impossible to act with empathy or compassion. They do it because it makes them money. It also makes them feel less alone.

Now throw social media into the mix. Suddenly, humans never get a break from each other. You can watch the news or fight with a total stranger 24 hours a day now, all while feeling insecure about your body and wondering if you should buy the latest Kardashian makeup kit.

Jamil Zaki describes the decline in empathy we’re seeing in The War for Kindness. Study after study reveals the same human flaw. When people get stressed, their capacity for compassion shrinks. It’s a mechanism of self-preservation. Their brains tell them to put themselves first.

“Screw everyone else.”

This evolutionary hangup works against our better traits, like collective action. It’s a tragic irony that as our existential threats grow, along with our need to cooperate, our desire to pull apart and attack each other also grows. It feeds a cycle of dehumanization and violence.![]() Netanyahu, Putin, Steve Harper and his ilk, the Fucker Truckers and Save the Children klan (many of whom abuse their kids and others) are excellent examples of this.

Netanyahu, Putin, Steve Harper and his ilk, the Fucker Truckers and Save the Children klan (many of whom abuse their kids and others) are excellent examples of this.![]()

Almost everyone lives under a daily deluge of stress now. They live under financial stress. They live with pandemic viruses. They live with war and genocide. They live with climate disasters that have an undeniable impact on everything from concerts to grocery shopping. They live with the stress of collapse, even if they try to hide it. Their technology amplifies it.

This stress manifests in all kinds of horrible behavior, on a local and global scale. Everyone has a mean streak, and that streak surfaces during times of high chronic stress. It pushes back against any attempts we make to unify in the face of our crises. It’s exacerbated by corrupt politicians and CEOs, who engineer scarcity and nurture our worse impulses for personal gain. For them, it’s not caused by stress. They were always like that.

The solution is simple but difficult.

Somehow, we have to convince everyone their survival depends on collective behaviors,![]() including dramatically reducing baby-making

including dramatically reducing baby-making![]() and that this rugged individualism is going to get everyone killed. Either that, or you have to become like Calhoun’s beautiful ones and get out while you can. In the end, we’re rats in paradise.

and that this rugged individualism is going to get everyone killed. Either that, or you have to become like Calhoun’s beautiful ones and get out while you can. In the end, we’re rats in paradise.

We’re in a behavioral sink.

That’s our problem.

Refer also to:

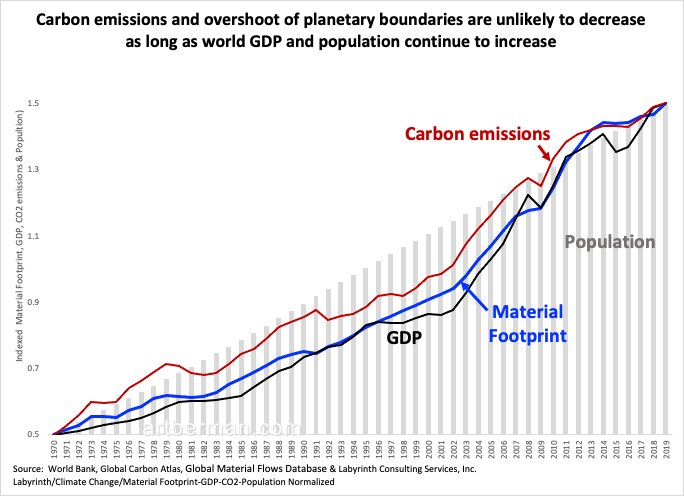

Prof. Eliot Jacobson@EliotJacobson Nov 26, 2023::

The “la la la” of zero carbon emissions is total f&%king bu&%sh&t.

Humans will always exploit all the resources they can to f&%k and make more humans.

That means carbon emissions will continue to rise just as long as there are humans.

That’s a primal truth, @michaelemann.