Toxic Landslides Raise Alarms about Fracking, Site C, Almost two years after slides began carrying heavy metals into creeks, few answers by Ben Parfitt, June 8, 2016, TheTyee.ca

Toxic heavy metals including arsenic, barium, cadmium, lithium, and lead are flowing into the Peace River following a series of unusual landslides that may be linked to natural gas industry fracking operations.

The landslides began nearly two years ago and show no sign of stopping. So far, they have killed all fish along several kilometres of Brenot and Lynx creeks just downstream from the community of Hudson’s Hope.

As plumes of muddy water laced with contaminants pulse into the Peace River, scientists and local residents are struggling to understand what caused the landslides and why they continue.

Hudson’s Hope Mayor Gwen Johansson is also worried about a broader question. The toxic metals are entering the Peace River in a zone slated to be flooded by the Site C dam. That zone could experience nearly 4,000 landslides if the dam is built, according to an assessment prepared for BC Hydro.

The risk alarms Johansson as BC Hydro, under the direction of Premier Christy Clark, pushes to advance work at Site C past “the point of no return.”

“If this much damage can result from tiny Brenot Creek, what happens to the reservoir if we get thousands more landslides?” the mayor asks.

No definitive cause of the Brenot Creek landslides has been determined. But one possibility is that they were triggered or exacerbated by natural gas industry fracking operations, in which immense amounts of water are pressure-pumped deep underground with enough force to cause earthquakes. Fracking is also known to cause unanticipated cracks or fractures in underground rock formations, allowing contaminated water, natural gas, oil and other constituents to move vast distances undetected.

A fracking boom, and leaking holding ponds

Fracking was under way in the area in the years immediately before the first slides were noted at Brenot Creek in August 2014.

Between July 2010 and March 2013, a dozen earthquakes ranging between 1.6 and 3.4 in magnitude occurred in the Farrell Creek fracking zone, about eight km from Brenot and Lynx creeks.

By March 2013, both B.C.’s Oil and Gas Commission (OGC) and BC Hydro were increasingly concerned about “events” at Farrell Creek, according to non-redacted parts of Freedom of Information requests to BC Hydro and commission documents.

“Right now our focus is on getting the improved seismographic network up and running,” Dan Walker, then the commission’s senior petroleum engineer wrote in an email to Andrew Watson, BC Hydro’s engineering division manager on April 7, 2013. “We will continue to monitor and study all cases of induced seismicity [earthquakes] in NEBC [northeast British Columbia].” The email was written two days after the last of the 12 earthquakes occurred at Farrell Creek.

By the time of that earthquake, Talisman Energy, the biggest natural gas company then operating at Farrell Creek, knew wastewater was leaking from one of four massive “retention ponds” it had built to store millions of litres of contaminated water from its fracking operations.

A detailed investigation paid for by Talisman and conducted by Matrix Solutions, an environmental engineering firm, notes that Talisman’s “leakage management system” detected that contaminated water was escaping from between two liners that were supposed to trap and prevent Pond A’s toxic brew from polluting the ground and water around it.

Pond A had likely been leaking for five months. In June 2013, Talisman drained the pond and confirmed the leaks had occurred. The OGC, which regulates B.C.’s oil and gas industry, subsequently ordered Talisman to drain the remaining three ponds. At that point, it was discovered that Pond D was also leaking toxic wastewater.

The wastewater ponds and gas reserves in the region are now owned by Progress Energy, owned in turn by Petronas, the Malaysian state-owned petro-giant. The provincial government is eager to see Petronas build a liquefied natural gas terminal at Lelu Island near Prince Rupert.

The toxic substances found in water samples collected from groundwater sources underneath Talisman’s faulty storage pits included arsenic, barium, cadmium, lithium, and lead, the same compounds found in the billions of fine sediment particles that continue to turn the waters of Brenot and Lynx creeks a muddy brown before they enter the Peace River.

The Matrix Solutions report, released in May 2015, noted the release of toxic metals was predictable. Digging the huge pits and exposing massive amounts of unearthed material to the air created the risk of “surface and groundwater acidification,” Matrix said.

“The primary concern for receiving environments related to acidic groundwater is the potential for release of trace metals,” the report warned.

‘Cows are not supposed to chew the water’

It’s not known if the fracking-induced earthquakes or the failures at Talisman’s waste ponds played any role in events at Brenot and Lynx creeks. No studies have been done in the region to determine how and where water moves below ground.

In its report of more than 2,200 pages, Matrix noted a troubling lack of groundwater information. “Flow direction is not documented,” the Matrix report said. However, the report noted that groundwater generally moves from “topographic highs toward topographic lows.” In other words, it moves downhill.

Below the Farrell Creek fracking zone, the waters of Lynx and Brenot creeks continue to be so full of contaminants that a person’s finger placed just a millimetre below the surface disappears from view. The pollution caused one local farmer to quip that his “cows are not supposed to chew the water.”

Martin Geertsema, a geomorphologist with the provincial Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations in Prince George, says he has never seen anything quite like what has the landslides at the site.

“We’ve got a camera pointed at the landslide,” he said in an interview. “I’d like to install a few more to try to figure out what the heck is going on. It’s very unusual. There’s nothing quite like this.”

“At other slide sites the water flows finished in a few days,” Geertsema said. “The difference here is it just keeps going. Water is coming out of the base and because the water is eroding soil from the base it leads to cliff collapse. And the cliff is composed primarily of sand and some clay. And when it collapses, the debris just flows.”

Geertsema noted the region is known for naturally occurring landslides, many of which show signs of “considerable antiquity.”

However, today’s slides are occurring in a region with some of the most extensive and intensive industrial land-uses in B.C., including two major hydroelectric dams and reservoirs and water-intensive fracking operations that the OGC has concluded in various locales in northeast B.C.

When the slides at Brenot Creek first began, the District of Hudson’s Hope advised residents not to drink the water and the provincial government issued a similar advisory a few days later.

The district later paid a hydrogeologist and water expert, Gilles Wendling, to collect and test water samples at the slide site to determine how toxic the water was.

Mayor Johansson remains disturbed by the event’s duration, its origins and — most of all — its timing. When the first landslide was discovered, the region had endured weeks of extremely hot and dry weather. A water-triggered landslide in August was, Johansson felt, highly unusual.

In January 2015, Johansson wrote an article in a district newsletter on the landslides and water contamination.

Environment ministry response ‘pretty inadequate’

“I have contacted MoE [B.C.’s Ministry of Environment] to ask what further steps they are planning and to find out when the advisory might be lifted,” she wrote. “The MoE representative said they have no plans to do anything further, other than file a report. He said he expected that eventually the creek would cleanse itself.”

“That seems pretty inadequate,” she continued. “Test results show levels of exotic metals such as lithium, barium, cadmium and others to be significantly above guidelines. They are not normally found in shallow ground or surface water. They have not shown up at those levels in any previous testing in the area, and I am not aware of similar readings being found anywhere in the northeast of the province. Some of the metals are toxic. They pose a risk to human and animal health.”

During a recent interview, Johansson said her views remain unchanged.

The OGC, which visited the site shortly after the slides began, concluded the contaminants were commonly found in the soils around the creek and that a natural spring was the source of the groundwater.

“The 2014 landslide appears to be entirely natural, and is one of a number of similar landslides that have occurred along Brenot and Lynx creeks over the last few hundred years, resulting from natural geomorphic processes,” Allan Chapman, the commission’s hydrologist reported in November 2014.

Chapman added that the landslide deposited “a moderate volume of fine-grained silt” into Brenot and Lynx creeks. “I would anticipate that these deposits along the stream channels will continue to release the elevated metals into the stream water, affecting the stream water quality, for an extended period of time,” he wrote.

But Wendling, the consultant hired by the district, has questions.

The slide was not a singular event, he noted in an interview from his Nanaimo office. Slides continue to occur there regularly.

Wendling said the only way to learn whether the presence of toxic metals in the water is natural would be to dig deep into the ground in the area of the slides and see whether the metals are found there. If they are not, and are being carried into the creek by groundwater, then where is the groundwater flowing from? And why does it continue flowing with such intensity so long after the first slides?

Such tests might shed light on whether major changes to the landscape, such as the nearby giant Williston reservoir and/or natural gas drilling and fracking operations, played a role in altering the direction in which groundwater flowed, Wendling said.

Wendling, an independent professional hydrologist, works closely with First Nation governments in the northeast who are concerned about the gas industry’s impacts on water resources. He said the high volume of groundwater entering Brenot and Lynx creeks, the contaminated soils being carried in that water and the timing slides are all of concern. Typically, he said, such events occur in the spring months following periods of intense rain and snowmelt. But this one appears to have occurred in the middle of a drought.

Shortly after the slides began, Wending walked the area and was struck by the dramatically different water levels upstream and downstream of the point Brenot Creek enters Lynx Creek. Upstream, Lynx Creek was virtually dry. Downstream, the creek had 50 times the normal water discharge.

“Why do two similar streams have such a difference in flows?” Wendling asked. It important to investigate all possible explanations for “the discharge of larger flows of shallow groundwater in proximity to Brenot Creek.”

However, no one is expecting any such investigations any time soon. Neither BC Hydro, the Oil and Gas Commission, provincial ministries nor the natural gas industry have groundwater flow monitoring wells in place.

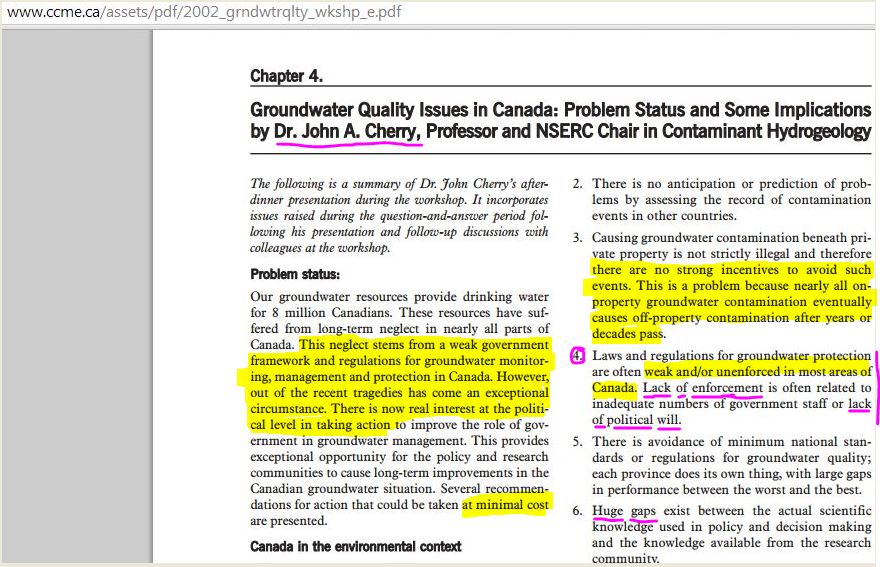

[Reality Check from Council of Canadian Ministers of the Environment 2002 workshop report, Chapter 4 by Dr. John Cherry:

What about all the 2014 frac monitoring/use us as guinea pigs song and dance by Dr. John Cherry and his Council of Canadian Academies frac review panel? Eg: “Everything’s fine, we just need to frac and study you a few more decades until the multinationals rape all their profits out.”

What was the purpose of Cherry’s Frac Review Panel? More Synergy Alberta promises to make sure the frac harms and poisoning continue, unabated, with zero accountability and no Duty of Care from any authority or company? Because our regulators and companies know how bad and toxic the impacts are?]

Geertsema laments the lack of information. [Instead of lamenting the lack of information, why not discuss how fortuitous that lack is for profit-taking oil and gas companies, how easy it makes things for regulators and how nicely it keeps lawsuits out of Canada’s overloaded courts (re, no “before” data to prove the endless contamination cases)?]

“I think it would be very useful to characterize groundwater flows,” he said. “It would help me and it would help the mayor whose backyard is where the problem is.”

It would also be extremely useful in light of another uncomfortable truth about earthquakes and their potential to alter groundwater flows and trigger landslides.

Dam reservoirs can bring spike in earthquakes

Hydroelectric reservoirs themselves can and do induce earthquakes. After the massive Three Gorges Dam was built in China, for example, more than 3,400 earthquakes were recorded in seven years after the dam’s reservoir began to fill in June 2003. The frequency of earthquakes was 30 times greater than before the dam.

A network of groundwater testing wells would help people in the region understand what might occur as the Site C dam goes from concept to potential reality over the coming years.

The reservoir that would be created by the dam would flood nearly 110 km of the Peace River valley and side valleys.

Should the dam be completed, rising waters are expected to cover ground vegetation that will react with the water to contaminate it with methylmercury, a substance that continues to poison fish in the massive Williston Reservoir nearly 50 years after the first dam on the Peace River, the W.A.C. Bennett Dam, was completed in 1968. First Nations people and anglers are warned not to eat fish from the artificial lake. Meanwhile, its shores continue to erode and slide into the reservoir, causing further contamination.

Johansson worries that other landslides like those at Brenot Creek could occur in future years, leading to a steady increase in the amount and variety of other waterborne toxins that could one day accumulate in the Site C reservoir.

Toxic water impounded by the dam would have to be released to power its hydroelectric turbines, meaning the water would then flow downstream toward the wildlife rich Peace-Athabasca delta, one of the world’s largest freshwater deltas and a critically important staging area for migrating birds.

Meanwhile, as Site C construction activities accelerate, members of UNESCO’s World Heritage committee are about to conduct a study into the impacts that the dam could have on Wood Buffalo National Park, a World Heritage Site. The investigation was prompted by a petition from Alberta First Nations concerned about the potential downstream impacts of the $9-billion hydroelectric project. The committee has asked the federal government to ensure that no irreversible work on Site C takes place until it has completed its report. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to:

2013: Lack of adequate procedures cause of Suncor rig blowout near Hudson’s Hope

Quebec First Nation wins case against government for 1918 dam that devastated the community by Christopher Curtis, Postmedia News, June 6, 2016, National Post

Nothing will erase the floods that washed away his ancestors’ homes, poisoned their drinking water and buried the hunting grounds that had sustained the Atikamekw Nation for hundreds of years.

But a recent legal victory over the federal government has put the Atikamekw within reaching distance of a lucrative settlement and an apology for the cataclysmic damage caused by the construction of the La Loutre dam in 1918.

“I think the federal government has a chance to make amends, to do the right thing,” said Awashish, an Atikamekw Grand Chief. “It’s not a perfect solution, it doesn’t take away what was done but it’s something we can live with.”

Last month, the Specific Claims Tribunal ruled that the federal government failed in its duties to warn the Atikamekw about the dangers of imminent flooding related to the 1918 project. The government did not properly compensate the First Nation for losing land, revenue from traplines and homes during the flood, according to four decisions signed by Quebec Judge Johanne Mainville.

The Mainville rulings mark the first time a Quebec First Nation has won a case before the Specific Claims Tribunal since it was created in 2008. The tribunal was established to deal with alleged treaty violations between the federal government and aboriginal groups.

“When I read the ruling, I almost screamed, ‘Victory!’,” said Awashish, whose great-grandfather was an Atikamekw chief at the time of the 1918 floods. “We were realistic about our chances, pessimistic even. We didn’t expect to win like that, to win so decisively. In those moments, after the decision was handed down, I thought about my ancestors, my great grandfather, about all these people who never got the chance to fight this in the courts.”

The rulings also concern flooding in the 1940s, the failure by the federal government to provide clean drinking water for the Atikamekw for decades and a years-long delay in creating reserve lands for the First Nation.

As lake water began to overtake the village, families had just enough time to salvage their clothes and blankets

The ministry of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development has until June 20 to contest the rulings, but a representative from the government would not say whether it would file an appeal.

“We are currently studying the rulings to determine what approach to take and what should be done next,” the spokesperson wrote in an email to the Montreal Gazette.

In the event of an appeal, the parties could be tied up in court for years. Even if the federal government abides by the decisions, it must sit down with the Atikamekw and negotiate a settlement, which could also take years.

Neither Awashish nor his band council’s lawyers would speculate as to the size of a potential settlement, but there’s a maximum payout of $150 million in decisions rendered by the tribunal.

For Quebecers living in the Haute Mauricie region, the 1918 creation of the La Loutre dam was a much-needed step toward modernity, a sign that progress and industry was making its way north to logging towns like La Tuque and Shawinigan.

But for the Atikamekw, who had thrived in the area for generations, the dam simply meant flooding on a biblical scale.

In historical documents unearthed during the hearings, it’s clear the dam posed an existential threat to the 160 Atikamekw settled in the village of Opitciwan — about 700 kilometres north of Montreal. As early as 1912, the provincial government’s own studies suggested most of Opitciwan would be submerged if the La Loutre dam were built near the territory.

And yet, in both documentary and oral evidence presented before the tribunal, no one appears to have warned the Atikamekw that they’d be hit with such devastation. As lake water began to overtake the village, families had just enough time to salvage their clothes and blankets.

Lawyers representing the federal government argued that because the dam was a provincial project, Quebec is ultimately liable for the Atikamekw’s plight. But the tribunal ultimately rejected those claims, reasserting the federal government’s responsibility to look after the well being of Quebec’s indigenous peoples.

“The federal government was either aware of the potential for a flood or it didn’t know but should have,” said Marie-Ève Dumont, one of the lawyers who represented the Atikamekw. “The information was available, there were many reports on record and ample evidence the government could have consulted. Ultimately, it was clear there would be flooding and not enough was done to mitigate its effects.”

About 20 homes were destroyed, along with the town’s chapel and two water wells at the time of the flood. The graveyard where 63 bodies lay would also permanently rest at the bottom of the lake.

Missionaries living among the Atikamekw wrote about rampant disease that followed the floods and of families forced to build shanties with scraps of wood to get through the brutal winters of the early 1920s.

The ramifications of the flood were huge, devastating even

Though the Quebec government promised the people of Opitciwan a shipment of lumber and construction materials to help rebuild their homes, the delivery took years to come. And when the delivery finally came, it didn’t include basic materials like doors, windows and hinges.

In a letter to the Quebec government, dated May 1922, one missionary wrote that four people in the village had died, that the village had become swampy, riddled with insects and that the priests feared “another epidemic.”

The town’s water supply and nearby fish stocks became contaminated with mercury. Even by 1944, nearly 30 years after the project began, federal inspection reports referred to the Atikamekw’s drinking water as “unsafe.”

But perhaps the most significant losses were the traps and other hunting tools washed away in the flood. Because the Atikamekw subsisted on hunting, trapping and fur trading, the disaster posed a threat to their most basic means of survival.

“The ramifications of the flood were huge, devastating even,” said Claude Gélinas, a Université de Sherbrooke professor whose work centres on the history of the Atikamekw peoples. “The inability to fish, to hunt totally upended the Atikamekw’s economy. It accelerated a process by which a nomadic people became sedentary and it began a cycle of dependence on government aid.”

For Awashish, last month’s victory was nearly 30 years in the making.

The Opitciwan band council began building its case in 1988 but was told repeatedly, by federal lawyers, that it had no recourse. It was only after the Specific Claims Tribunal was established in 2008 that the Atikamekw finally got their day in court.

By then, however, many of the elders who were children during the floods of the 1940s had died. Still, four Opitciwan elders testified before the tribunal in 2013 and their testimony weighed heavily in the decision — according to Justice Mainville’s rulings.

“It makes me really proud that our elders were heard and that their experience was given such prominence,” said Awashish.

In the event of a cash settlement, Awashish said he’ll hold consultations with his community but that some of the reserve’s needs are pressing. Opitciwan is among Quebec’s most impoverished communities — with unemployment rates frequently floating above 50 per cent, overcrowded living conditions and a badly underfunded school system.

“We want to create an education fund, to get some money in housing, to invest in our children, in our future generations,” said Awashish. “But we’re not there yet, we know we still have a long road ahead of us.”

Gélinas says that despite their immense challenges, there’s reason to be hopeful about the future of the Atikamekw.

“I’m an optimist and when I look at Opitciwan, I see a young population and children who, if they’re given the right tools, can succeed,” said Gélinas. “We’ve seen plenty of success stories come out of Quebec First Nations and I think we can see plenty more.” ]