Toxins Found in Fracking Fluids and Wastewater, Study Shows January 6, 2016 by Stone Hearth News

Newswise — In an analysis of more than 1,000 chemicals in fluids used in and created by hydraulic fracturing (fracking), Yale School of Public Health researchers found that many of the substances have been linked to reproductive and developmental health problems, and the majority had undetermined toxicity due to insufficient information.

Further exposure and epidemiological studies are urgently needed to evaluate potential threats to human health from chemicals found in fracking fluids and wastewater created by fracking, said the research team in their paper, published Jan. 6 in the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental and Epidemiology.

The research team evaluated available data on 1,021 chemicals used in fracking, a process that recovers oil and natural gas from deep within the ground by using a mixture of hydraulic-fracturing fluids that can contain hundreds of chemicals. The process creates significant amounts of wastewater and fractures the bedrock, posing a potential threat to both surface water and underground aquifers that supply drinking water, note the researchers.

… Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology advance online publication 6 January 2016; doi: 10.1038/jes.2015.81

Toxins found in fracking fluids and wastewater, study shows by Michael Greenwood, January 6, 2016, YaleNews

In an analysis of more than 1,000 chemicals in fluids used in and created by hydraulic fracturing (fracking), Yale School of Public Health researchers found that many of the substances have been linked to reproductive and developmental health problems, and the majority had undetermined toxicity due to insufficient information.

Further exposure and epidemiological studies are urgently needed to evaluate potential threats to human health from chemicals found in fracking fluids and wastewater created by fracking, said the research team in their paper, published Jan. 6 in the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental and Epidemiology.

The research team evaluated available data on 1,021 chemicals used in fracking, a process that recovers oil and natural gas from deep within the ground by using a mixture of hydraulic-fracturing fluids that can contain hundreds of chemicals. The process creates significant amounts of wastewater and fractures the bedrock, posing a potential threat to both surface water and underground aquifers that supply drinking water, note the researchers.

While they lacked definitive information on the toxicity of the majority of the chemicals, the team members analyzed 240 substances and concluded that 157 of them — chemicals such as arsenic, benzene, cadmium, lead, formaldehyde, chlorine, and mercury — were associated with either developmental or reproductive toxicity. Of these, 67 chemicals were of particular concern because they had an existing federal health-based standard or guideline, said the scientists, adding that data on whether levels of chemicals exceeded the guidelines were too limited to assess.

“This evaluation is a first step to prioritize the vast array of potential environmental contaminants from hydraulic fracturing for future exposure and health studies,” said Nicole Deziel, senior author and assistant professor of public health. “Quantification of the potential exposure to these chemicals, such as by monitoring drinking water in people’s homes, is vital for understanding the public health impact of hydraulic fracturing.”

[A few questions:

After many are sick or dead, along with pets, wildlife, fish and livestock, will frac companies and their enabling politicians, academics, public health agencies, research councils and de-regulators like AER, disclose complete drilling, blowout, cementing, acidizing, fracing, leak & frack hit repair, and servicing chemical details needed to finally fully assess the water, air, food and health harms?

Community of Rosebud, Alberta:

The Nightmare of Ann Craft, Ponoka, Alberta:

Diana Daunhemier and family, Didsbury, Alberta:

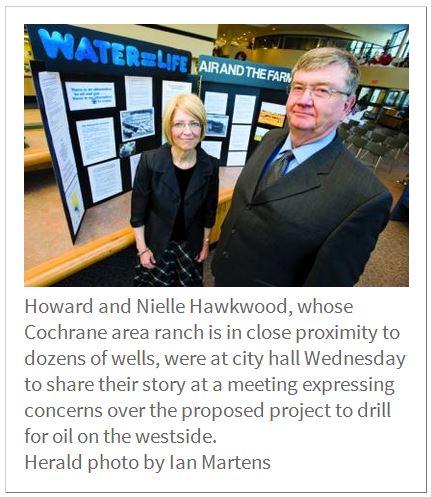

Howard and Nielle Hawkwood, Lochend, Alberta

What’s killing their livestock?

What’s in the air and water?

What’s making Nielle’s hair fall out?

Ronalie and Shawn Campbell, Ponoka, Alberta

What were they breathing venting from their taps, bathing in and drinking?

Dale and Brenda Zimmerman, Wetaskiwin, Alberta.

What’s the family living with, what were they breathing, bathing in, drinking?

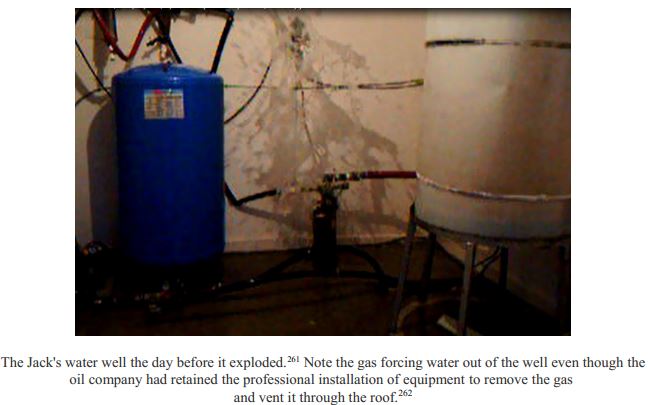

Loraine and Bruce Jack, Spirit River, Alberta.

Never mind the methane and ethane that blew up Jack’s water well, what else is in the water? What were the Jacks breathing venting from their water taps, bathing in, drinking?

What made Alberta Environment Deputy Minister Peter Watson (later appointed by Harper government to Chair NEB) dash to Jack’s bedside promising alternate water if Jacks kept quiet?

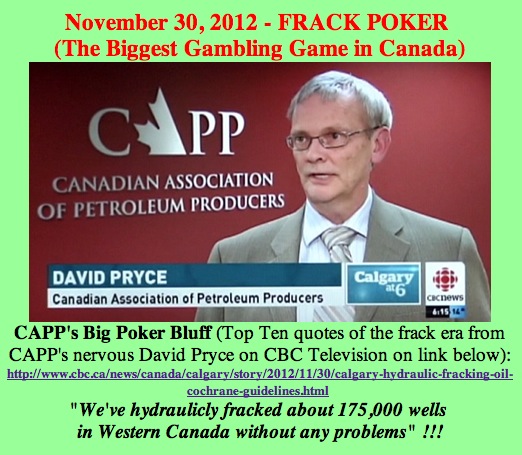

Who’s investigating the fractured caprock and AER & CAPP fraud?

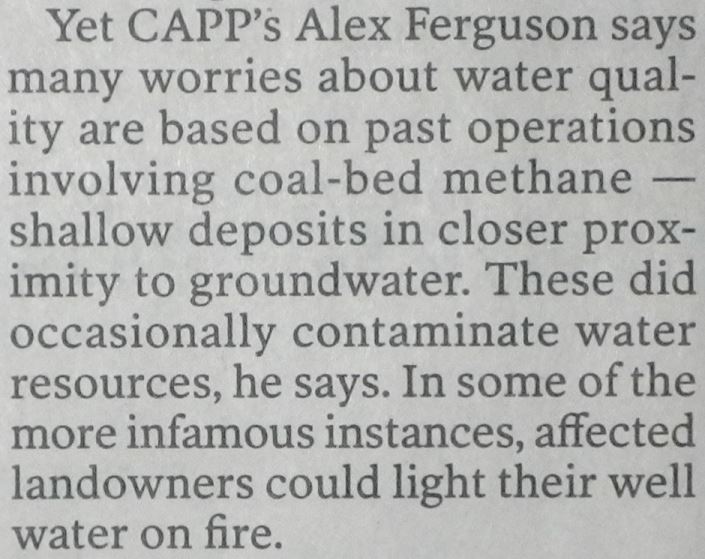

Two years later, August 28, 2014

CAPP confession in the Calgary Herald:

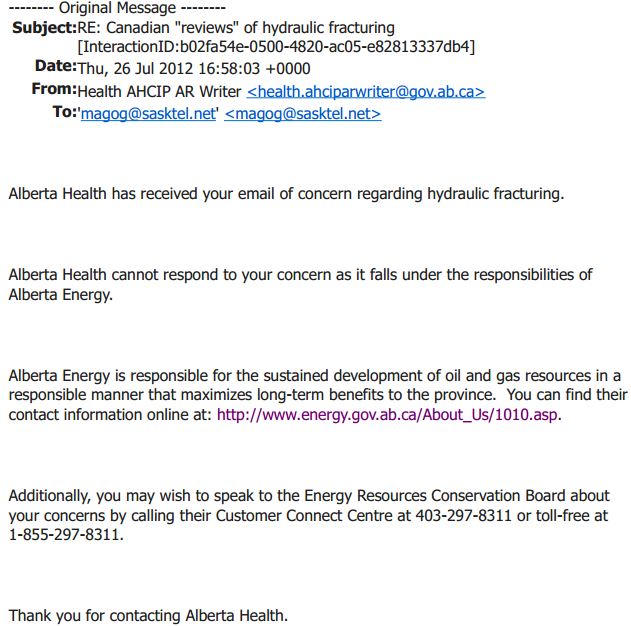

Where’s Alberta Health?

Where’s Health Canada?

Are they silent because of how frac harms are “studied” in Canada?

***

Some previous studies have observed associations between proximity to hydraulic fracturing sites and reproductive and developmental problems, but they did not investigate specific chemicals. This latest evaluation could inform the design of future studies by highlighting which chemicals could have the highest probability of health impact, note the researchers.

… “We focused on reproductive and developmental toxicity because these effects may be early indicators of environmental hazards. Gaps in our knowledge highlight the need to improve our understanding of the potential adverse effects associated with these compounds,” said Elise Elliott, a public health doctoral student and the paper’s first author.

The researchers determined that wastewater produced by fracking may be even more toxic than the fracking fluids themselves. This led the researchers to conclude that more focus is needed to study not just what goes into the well, but what chemicals and by-products are generated during the fracking process.

The researchers also noted that the 781 chemicals for which information is currently lacking need to be rigorously analyzed to determine if they pose health threats.

In addition to Deziel and Elliott, the research team included Yale School of Public Health Deputy Dean Brian Leaderer; Michael Bracken, the Susan Dwight Bliss Professor of Epidemiology (chronic diseases); and Adrienne Ettinger, an assistant professor at the school when the research was conducted. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to: