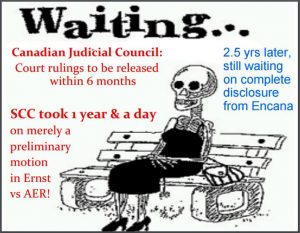

Won’t that be something if the Supreme Court rules corporations are protected under the Charter but Ernst is not, ie the same court ruled Ernst cannot sue the AER for her valid claim of the regulator violating her Charter rights.

Supreme Court of Canada / Cour suprême du Canada

(le français suit)

JUDGMENTS IN LEAVE APPLICATIONS

July 25, 2019

For immediate release

OTTAWA – The Supreme Court of Canada has today deposited with the Registrar judgments in the following applications for leave to appeal.

JUGEMENTS SUR DEMANDES D’AUTORISATION

Le 25 juillet 2019

Pour diffusion immédiate

OTTAWA – La Cour suprême du Canada a déposé aujourd’hui auprès du registraire les jugements dans les demandes d’autorisation d’appel qui suivent.

GRANTED / ACCORDÉE

Procureure générale du Québec et directeur des poursuites criminelles et pénales c. 9147-0732 Québec inc. (Qc) (Criminelle) (Autorisation) (38613)

La demande d’autorisation d’appel de l’arrêt de la Cour d’appel du Québec (Québec), numéro 200-10-003462-178, 2019 QCCA 373, daté du 4 mars 2019, est accueillie.

L’échéancier pour la signification et le dépôt des documents sera fixé par le registraire.

The application for leave to appeal from the judgment of the Court of Appeal of Quebec (Québec), Number 200-10-003462-178, 2019 QCCA 373, dated March 4, 2019, is granted.

The schedule for serving and filing materials will be set by the Registrar.

Summary 38613 Attorney General of Quebec, et al. c. 9147-0732 Québec inc.

(Quebec) (Criminal) (By Leave)

Keywords

Canadian Charter (Criminal) – Cruel and Unusual Treatment or Punishment (Clause 12) – Charter of Rights – Cruel and Unusual Treatment or Punishment – Application of Charter Rights to Legal Persons – Breach of Commercial Corporation for Having Offended undertaken construction and entrepreneurial work without a valid license – Provincial Building Act provides minimum mandatory fine of $ 30,843 – Is protection against “all cruel and unusual treatment or punishment” provided for in section 12 of the Charter can apply to legal persons? – Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, ss. 12 – Building Act, RLRQ c B 1.1, art. 46, 197.1.

Summary

The file summaries are prepared by the Office of the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada (General Directorate of Law). Please note that they are not sent to the judges of the Court; rather, they are placed on the Court’s file and posted on its website for information purposes only.

The respondent, a private commercial corporation, was issued a statement of offense under the Quebec Building Act for undertaking certain contractor and construction work without holding a valid license for that purpose . The penalty for such an offense provided for in art. 197.1 of the Act is a mandatory fine, the minimum amount of which varies according to the offender’s identity, c. to d. if it is a natural or legal person. The respondent files a notice of contestation of the constitutional validity of the fine provided for in art. 197.1, alleging that it violates its right of protection against “any cruel and unusual treatment or punishment” under s. 12 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

At first instance, the Court of Québec concluded that it was not necessary to rule on the question of the application of s. 12 of the Charter to legal persons, since the minimum fine in question was not, in any event, cruel and unusual. The respondent is found guilty and a fine of $ 30,843 is imposed. On appeal, the Quebec Superior Court upheld this decision, adding that legal persons, like the respondent, can not benefit from the protection provided by s. 12 of the Charter.

A majority in the Quebec Court of Appeal invalidates the decisions of lower courts and concludes that s. 12 of the Charter may apply to legal persons. She returns the record at first instance to decide the question with respect to the fine provided for in art. 197.1 of the Act.

Refer also to:

Canada’s Federal Interpretation Act’s section 10 Section 35 (1)(d) person, or any word or expression descriptive of a person, includes a corporation…

Alberta’s Interpretation Act at section 28 subsection (nn) “person” includes a corporation……

****

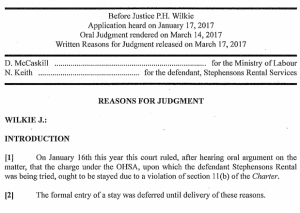

Ruling on a similar matter, dated March 17, 2017

Snaps below taken from the ruling.

Look how speedily the ruling came down! Two months! Why so fast? Because a corporation won?

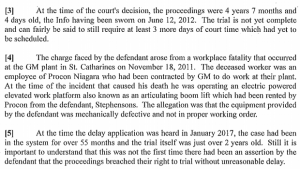

Compare to Supreme Court of Canada taking a year and a day to rule in merely a preliminary matter in Ernst vs AER! Canadian citizens are treated like garbage in our courts compared to criminals and corporations, even corporations causing fatalities.

Corporations also protected from trial delay: court by Advocate Daily.com, March 2017

The Ontario Court of Justice decision to stay a charge under the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA) against a corporation over a trial delay is “an important ruling that sends a strong message,” says Toronto regulatory, employment and white collar investigations and defence lawyer Norm Keith.

Keith, a partner with Fasken Martineau, was successful in arguing for the stay for his client Stephenson’s Rental following a 2011 workplace fatality at a St. Catharines General Motors plant. Charges were laid in June 2012.

The trial had taken more than 55 months to proceed and still faced another five months, Superior Court Justice Peter H. Wilkie said in his decision.

Wilkie, citing the July 2016 Supreme Court of Canada R. v. Jordan [2016 SCC 27] decision — the case of a drug dealer whose charges were stayed after a four-year delay — also stayed the charges against Stephenson’s, blasting the Crown for failing to better manage “the pace of litigation.”

“The previous standard at the Supreme Court of Canada was R. v. CIP Inc. [R. v. CIP Inc., [1992] 1 S.C.R. 843] which said there was a higher standard for corporations over individuals,” says Keith noting the court also considered R. v. Morin [1992 1 SCR 771].

“Jordan changes all that as does this decision,” he says. “Corporations have the same full rights to a trial in a reasonable time as an individual, regardless of whether it’s a Criminal Code violation or an OHS charge.”

Keith tells AdvocateDaily.com his client’s trial was never given the timely priority by the Ministry of Labour and the judicial system that it deserved. The case involved a worker using an articulated boom lift supplied by the equipment rental company when the incident occurred.

The Ontario Ministry of Labour alleged the equipment was mechanically defective and not in proper working order. The trial started in December 2014 at which point Keith brought a Charter challenge under Section 11 (b) alleging the process was taking too long.

At that point, as Wilkie noted in his reasons, the process involved 13 appearances over 19 months before a trial date was set. Also, as Keith argued, the defence still hadn’t received full disclosure of the Crown’s case against his client.

The delays continued, Wilkie stated, as did the lack of disclosure, and on the day the trial was finally going to start the Crown appeared with two binders of evidence it handed to the defence.

With no time to review or prepare a defence because of the new disclosure, the trial was adjourned again. The matter dragged on to September 2016.

“By July that summer, of course, we have the Jordan decision from the Supreme Court of Canada,” says Keith who went back to court in January this year and won the stay because of the delay. “While that case addressed charges against an individual, I argued that it should also apply to corporations.”

The judge agreed: “The total delay at the point when the court indicated its decision to grant the (delay of trial motion) was 55 months and four days.”

Even if the trial had proceeded it could have taken another five months, the judge noted in the written decision released in March 2017, adding the defence was only unavailable on nine of the days in question and the rest of the delay was attributable to the prosecution.

In one incident, the Crown’s expert witness had mistakenly scheduled eye surgery on a day he was to testify, causing further delay.

“In my view it is apparent that the Crown made no efforts to manage the case so as to improve the pace of litigation but in fact through lack of focus and inaction further contributed to the delay,” wrote Wilkie, noting in his experience in the Niagara court region, the trial would still have been delayed 18 months, which again would have triggered a Charter argument.

Keith says the important point is that the court took the corporate client’s Charter rights seriously and applied the full effect of Jordan. The Crown argued it was “exceptional,” because the case was so complicated and Jordan shouldn’t apply and, failing that, “transitional” in that the July Supreme Court of Canada ruling came out while their case was still in progress.

“Taken as a whole, Jordan is a good decision that will speed the administration of justice. American courts have done a better job in this area though they have been called ruthless,” Keith says.

In that vein, Wilkie laid the blame at the feet of the Crown: “The Crown principally due to its ongoing failure to provide timely disclosure and its overall complacency about the pace of the litigation is responsible for the vast majority of the delay with the rest accounted for by institutional time constraints.”

The message emerging from the courts seems clear, says Keith, who was also featured in a Canadian Lawyer blog post on the decision.

“It’s a strong message that unreasonable delay in any type of prosecution, including quasi-judicial charges against corporations, will not be tolerated by the judiciary,” Keith says. “The judges are saying the administration of justice across the board needs to be more expeditious and more responsibly managed by prosecutors.”

[But, OK for Canada’s Top court to take a year and a day to rule in merely a preliminary matter in Ernst vs AER?]

Jordan cited as reason for charge being stayed in workplace fatality, Judge stays charge, slams Crown for delays in workplace fatality case by Jennifer Brown, 21 March 2017, Canadian Lawyer Mag

An Ontario judge has stayed a Ministry of Labour charge against a company accused in a workplace fatality because the matter dragged through the system for 55 months and the trial was more than two years old.

In yet another application of R. v Jordan, on March 17, Justice Peter Wilkie of the Ontario Court of Justice stayed a charge in R. v. Stephenson’s Rental Services, saying the right of the defendant to be tried within a reasonable time under s. 11(b) of the Charter had been breached.

“The defendant’s trial has clearly been unreasonably delayed whether the analysis is under the Jordan framework or that of Morin. The Crown principally due to its ongoing failure to provide timely disclosure and its overall complacency about the pace of the litigation is responsible for the vast majority of the delay with the rest accounted for by institutional time constraints,” Wilkie wrote.

Justice Wilkie also stated: “In my view it is apparent from the court’s summary of the chronology of the trial itself, that the Crown made no efforts to manage the case so as to improve the pace of litigation but in fact through lack of focus and inaction further contributed to the delay.”

While there have been a couple of other stays issued under Jordan, Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP lawyer Norm Keith predicts there may be more to come.

“I think prosecutors at the Ministry of Labour and other government departments have not been paying attention to corporations who are in the process of being prosecuted simply because they assumed maybe that Jordan didn’t apply, but this case definitively asks does Jordan supersede CIP [R. v. CIP Inc.], which sets a higher test for prejudice for a corporation than an individual.

“CIP basically said you can’t presume prejudice just because of a long delay under s. 11(b) — you have to prove as the corporate defendant that you have suffered irremediable prejudice,” says Keith, who represented Stephenson’s Rental in the case.

And in his decision, Wilkie states: “. . . at the heart of Jordan is the objective to change the culture of delay in the justice system as a whole and to require all trials to function as efficiently as possible. In this sense they have signaled that when section 11(b) is breached it is not just the particular defendant who is prejudiced but the justice system and by extension the community as a whole. There is no basis for concluding that this objective applies only to trials of individuals.”

…

Keith says the Crown was arguing it was a complicated case with expert witness material involved. However, the judge pointed out the Crown had taken too long to turn its mind to the expert witness material.

“There is no question that the expert disclosure did take the Crown by surprise, but only because they had to that point, well into the trial, at least 2 years after he had been retained by the Ministry to provide critical expert testimony, inexplicably in my view, failed to turn their mind to it,” said Wilkie.

Keith admits he himself was responsible for a about nine days of the delay in August 2015 due to a scheduling issue, but other than that, the judge said when it came to the defence, “there was no waiver and no tactic calculated to cause delay.”

It then took about a year from the time the expert first gave evidence to get him back on the witness stand.

“Even the witness himself seemed surprised that he had never been asked to produce his work product beforehand or to bring supporting documentation with him to court,” Wilkie stated in his decision. “And of course when alerted to the issue, the Crown readily agreed that the defence was entitled to disclosure of the material and conceded the case would have to be adjourned to enable the defence to receive and review it.”

Given the way the case unfolded, it seems like a more “unique matter”, says Jeremy Warning, partner with Mathews Dinsdale & Clark LLP in Toronto.

“Typically you don’t see protracted disclosure issues like it appears occurred in the Stephensons case where the defence had been chasing material, it appears, for quite some time and then on the eve of trial is disclosed a fairly voluminous amount of documents and materials to review,” says Warning.

In terms of the facts set out, Warning says the case is “different from what one normally sees” with Ministry of Labour cases.

“It’s unfortunate that this case didn’t proceed as expeditiously as the law says it should because a stay of proceedings has denied a verdict on the merits — I’m not suggesting there had been an offence — but the merits were never determined and never will be determined,” says Warning.

“In terms of the administration of justice there is some erosion of the judicial process in the fact the charges had to be stayed but one has to balance the societal interest in achieving a verdict on the merits against the individual interest of the defendant to have a trial in a reasonable time when they can fairly challenge the evidence advanced by the prosecution. That’s an equally compelling consideration.”

The net delay was at least 60 months — 41 months above the presumptive ceiling.

As Jordan was decided the first week of July 2016 and the Stephenson’s case started in December 2014, the Crown had argued the Jordan 18-month rule didn’t apply.

But the judge disagreed, even noting that the Region of Niagara was not one where a culture of long delays was the norm.

“Ultimately, the right to trial within a reasonable period of time of the accused, be it individual or corporate, is superseding the social interest of a trial going to final decision,” says Keith.

Crown officials say they are “carefully reviewing” the Court’s decision to determine if there will be an appeal. “The matter remains before the court during the appeal period, and in order to preserve the fairness of the process, we will not comment on the case, specifically,” said spokesperson Janet Deline.

“Without commenting on the merits of the decision, we do want to assure families and loved ones that we continually review our processes to ensure we do everything we can to protect workers and ensure just results.”

In a case such as this, a corporation facing conviction could face a fine in the range of $100,000 up to $500,000.

Update: March 29, 2017: Comments added from Jeremy Warning of Mathews Dinsdale & Clark LLP, and Ministry of Labour.