Following Sudden Death of Indicted Former Chesapeake Energy CEO, Justice Department Investigation into Collusion Continues by Sharon Kelly, March 8, 2016, desmogblog

Last Tuesday, the Justice Department announced criminal charges against former Chesapeake Energy CEO Aubrey McClendon, stemming from an alleged lease bid-rigging conspiracy between McClendon and another unidentified oil and gas company. The felony count against McClendon carried up to a decade in prison and $1 million in fines.

Shortly after 9 AM the next day, McClendon crashed his SUV at over 50 mph into a concrete highway overpass and died instantly of blunt force trauma. Police are continuing to investigate McClendon’s cause of death, awaiting toxicology results and other data, and have not ruled out the possibility that the car wreck may have been a suicide.

“He pretty much drove straight into the wall,” Oklahoma City Police Department Capt. Paco Balderrama told a local NBCaffiliate. “There was plenty of opportunity for him to correct and get back on the roadway and that didn’t occur.”

The dramatic exit of one of the most flamboyant wildcatters in the shale rush stunned many observers — and his abrupt death may serve to pull attention away from the underlying crimes that McClendon was so recently accused of committing. The acts McClendon, age 56, stood accused of occurred at the height of the shale land rush and were committed in his role as then-CEO of Chesapeake Energy, the nation’s second largest natural gas producer.

Before McClendon died, Forbes writer Chris Helman noticed something very interesting in the former CEO‘s response to his indictment: McClendon didn’t deny the acts underlying the charges, he simply argued that others in oil and gas industry also engaged in the same conduct.

“I have been singled out as the only person in the oil and gas industry in over 110 years since the Sherman Act became law to have been accused of this crime in relation to joint bidding on leasehold,” McClendon had said in a statement on Tuesday.

The day after McClendon’s death, prosecutors filed to formally drop the criminal charges against him as moot.

The question becomes what comes next for the Justice Department, now that the only individual person named in the criminal indictment is beyond the reach of the law. If others in the industry have indeed acted similarly, are further indictments coming? [Encana CEOs, current and past, getting sweaty? How about Ex_Encana-VP Gerard Protti?]

The indictment does not identify the company that McClendon ran by name, and it refers to his alleged co-conspirators only as “Company B” and “Co-conspirator 1.”

Although a small handful of companies had business dealings with Chesapeake in the time and place described in the indictment, Bloomberg quickly reported that SandRidge Energy Inc., and its former CEO Tom Ward, a long-time associate of McClendon’s, were most likely the co-conspirators.

For its part, Chesapeake Energy has said that it is cooperating with federal investigators and that therefore it does not anticipate facing penalties. “Chesapeake does not expect to face criminal prosecution or fines relating to this matter,” Chesapeake spokesman Gordon Pennoyer said in a statement.

However, in its recently released annual Securities and Exchange Commission filings, Chesapeake warned its investors that the Department of Justice was investigating its actions in “various states,” in relation not only to its leasing practices but also to the royalties the company pays to landowners after the lease is signed, and that Chesapeake had received multiple subpoenas from federal and state investigators.

The feds had accused McClendon of participating in a conspiracy to keep the prices paid to landowners who leased their lands for drilling in Northwest Oklahoma artificially low. “During this conspiracy, which ran from December 2007 to March 2012, the conspirators would decide ahead of time who would win the leases,” the Justice Department wrote in describing the charges.

The notion that this kind of bid-rigging conduct McClendon stood accused of may have been criminal appears to have shaken many.

“The entire oil and gas industry has been watching this investigation because it could have broader implications on the industry,” Energy & Minerals Group Chief Executive Officer John Raymond said in a letter to investors, according toBloomberg.

The harms done by McClendon’s alleged criminal acts are substantial — individual landowners suffered, as they would have received a smaller share of the returns from drilling than they might have if the shale leasing process had been truly competitive. [On top of their loved ones being poisoned and having their water contaminated?]

“If this is true and it was fairly widespread, Chesapeake made a bunch of money that it probably shouldn’t have made,” Jim Bradbury, a Texas environmental attorney told E&E News after the indictment was announced. “Every nickel the royalty owner didn’t get, the company owner did get.”

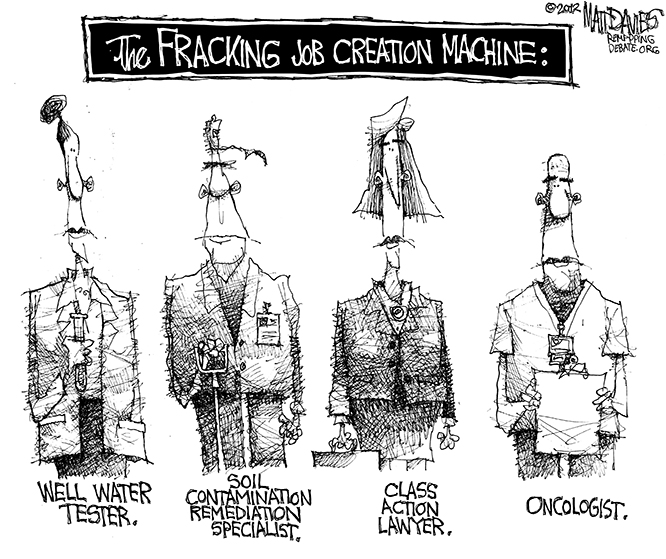

But the societal harm from anti-trust violations in the shale drilling industry runs far broader than the harm done to individual landowners.

By artificially driving down the costs of leases, companies like Chesapeake [and Encana] would have been able to buy up far larger swaths of land for drilling. This buying spree in turn spurred the shale gas land rush and the boom in hurried drilling to secure leaseholds.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of leasing for McClendon and the companies he ran. “Geologists and engineers were the important guys—but it dawned on me pretty early that all their fancy ideas aren’t worth very much if we don’t have a lease,” McClendon had said. “If you’ve got the lease and I don’t, you win.”

And throughout the land rush, drillers paid heavily to lock in shale acreage. In the span of just three years — 2009 to 2012 — oil and gas companies spent over $461 billion on leasing the rights to drill from North American properties, a 2013 Bloomberg investigation concluded.

Because of contractual requirements to drill in order to hold leases “by production,” that land rush was fast followed by a drilling frenzy that has fed a supply glut even as fossil fuel prices have plunged.

What does this all mean? If it were not for the illegal anti-competitive acts like those described in the indictment, the shale rush may never have spread so far so fast — and other renewable sources of energy could likely have been far more competitive against natural gas in terms of price.

While the criminal acts described in last Tuesday’s indictment occurred in one corner of Oklahoma, some legal experts suspect that this type of collusion was far from rare during the shale land rush. “I don’t think it’s uncommon,” Denver, COattorney Lance Astrella told The Washington Post.

Chesapeake previously paid over $25 million to settle charges of racketeering, fraud and anti-trust violations over a similar alleged conspiracy with Encana in Michigan.

McClendon’s legal team itself argued that these tactics were both common and had helped to lower fossil fuel prices.

“The Justice Department has taken business practices well-known in the Oklahoma and American energy industries that were intended to, and did in fact, enhance competition and lower energy costs,” they wrote in a statement on Tuesday, “and twisted these business practices to allege an antitrust violation that did not occur.”

After McClendon’s death, the Justice Department indicated that its overall investigation into the industry remains ongoing. [Where’s the investigation into the criminal activities by the industry in Canada? Any Attorney General with some courage?]

The charges of financial improprieties comes at a time when the shale drilling industry seeks to reassure investors of its long-term prospects. A wave of bankruptcies has already swept across the U.S., with at least 67 oil and gas companies going under last year.

In December, CNN reported that 50 percent of oil and gas junk bonds were “distressed,” or at risk of default — and the shale rush has been fueled in large part by junk bond debt. In places where drillers promised jobs for decades, layoffs have crippled local economies.

Meanwhile, wind and solar firms have managed to continue their slow and steady expansion despite the sharp swings in oil and gas prices.

“We’re not saying there’s no impact, but we’re not seeing a significant impact yet,” Angus McCrone, Bloomberg New Energy Finance chief editor told National Geographic in January. “There’s a lot of momentum behind clean energy.”

Some legal experts have speculated that the Justice Department had focused on McClendon as the man orchestrating the bid-rigging scheme, allowing his co-conspirators to avoid prosecution and remain anonymous in the indictment in return for their cooperation. But if the bid rigging schemes were indeed as common as McClendon suggested, the investigation into collusion in the shale land rush could only be getting started.

“I think this case represents a coming trend of DOJ antitrust prosecutions,” attorney Philip Hilder, who formerly was head of the Justice Department’s Houston office, told The Houston Business Journal. “The antitrust division, along with the rest ofDOJ, is putting an emphasis on individual accountability and responsibility.” [Emphasis added]

From Boomtown to Ghost Town? by Dave Bohman, March 7, 2016, wnep.com

SAYRE — Falling natural gas prices and the financial troubles of Chesapeake Energy have turned parts of Bradford County from boom to bust in relatively a short period of time.

Bradford County has more natural gas wells than any other county in our state. Almost all of those wells are operated by Chesapeake Energy.

But the corporation’s layoffs, falling stock price, and its recent decision to stop drilling new wells threaten to slowly turn boomtowns into ghost towns.

Downtown Sayre sits three miles from Chesapeake Energy’s regional corporate headquarters. Empty storefronts now dot the main streets.

In nearby neighborhoods, homeowners who want to leave to find work, either can’t sell their houses or sell at a loss.

“They bought when the market was at its peak high,” said Stephanie Johnston. [Is greed dooming humans to never learn from the endless past oil patch boom-busts around the world?]

Johnston left her job as an office manager three years ago, thinking real estate would be the perfect career at a time when natural gas was employing her neighbors in northern Bradford County.

“I seem to be catching the aftermath of the big boom that we had experienced,” said Johnston.

She and many others say the region rose and fell with the fortunes of Chesapeake Energy, a company whose stock has fallen as its operations in Bradford County are tapering off.

Chesapeake is still taking gas out of the ground in Bradford County, but the corporation announced it won’t be drilling any new wells in 2016.

Chesapeake’s decline can be seen in Athens Township at the company’s “man-camp” which once housed about 200 workers in modular homes.

“It was booming. The town and everything was booming,” said Dale Wade.

Dale Wade and Josh Nichols pass the man-camp daily on their way to work at a cabinet factory near Athens. They don’t see much there anymore, only an occasional security guard checking buildings.

“Since I first started, when I started working here, the place was packed. Now it’s a ghost town,” Nichols said.

“It’s sad because there’s a lot of jobs that’s gone right there,” Wade added. [What? Like in Canada? What about those many thousands of permanent jobs jobs jobs promised by politicians, regulators, industry to come to all communities that let fracing in? ]

Some blame the troubles of Chesapeake and the natural gas industry for a rise in job losses.

At the beginning of 2009, Bradford County’s unemployment rate stood at 9.7 percent.

By the end of 2014, it fell to 4.4 percent.

Last year it finished at 5.1 percent and most there believe it will continue to rise while business is slow.

Joe Frank used to test water for gas drillers. When that business could only give him part-time work, he made a career change. He bought a restaurant in Sayre, and re-named it “Frank’s Franks.”

“Recently, I was laid off. And now I’m trying to operate a hot dog stand on the side and trying to make ends meet that way,” Frank said.

“Recently, I was laid off. And now I’m trying to operate a hot dog stand on the side and trying to make ends meet that way,” Frank said.

“People are getting into different financial situations like bankruptcy,” said Johnston.

Johnston hopes Chesapeake makes a comeback in Bradford county soon. Jobs and home buyers are hard to find.

“We become friends with our clients, and to hear their struggles and trying to get the amounts that they need, it’s just kind of heartbreaking.”

At its annual meeting last month, Chesapeake executives said the company could resume drilling new gas wells in Bradford County when natural gas prices get better, but no one at the company would say when prices will make drilling profitable enough. [Emphasis added]

The Greek tragedy of the billionaire who fracked up Pa by Philadelphia Daily News, March 3, ,2016

Fracking – the controversial technique of drilling for natural gas and oil – claimed some new victims in Pennsylvania yesterday: A once-majestic stand of maple trees that the Holleran family of Susquehanna County has been working to produce maple syrup since the 1950s. A big pipeline firm, the Williams Companies, successfully used the right of eminent domain to win the right to clear the Hollerans’ stand of trees to make way for a new pipeline intended to carry to natural gas fracked from the Marcellus Shale to large urban markets.

According to StateImpact PA, at least three U.S. Marshals armed with semi-automatic weapons and pistols and wearing bulletproof vests were there to protect the pipeline workers from about 20 peaceful protesters carrying signs that read “No Eminent Domain for Corporate Gain” and “Sap Lines Not Pipelines.”

It was just one more way that the fracking boom has ripped Pennsylvania – and Pennsylvanians – apart since its gold-rush mentality swept through big chunks of the northern and western corners of the commonwealth about a decade ago.

It was right around the moment that the first chainsaw was cutting into maple bark when a newsflash swept through the business world and beyond: Aubrey McClendon — the ostentatious Oklahoma billionaire who was also essentially the godfather of our Pennsylvania fracking explosion, enmeshed in controversy until his final hours – had died under murky circumstances.

In little more than a decade, the former CEO of the once high-flying Chesapeake Energy had come to symbolize first the promise of tapping fossil fuels trapped deep beneath this American soil, and then the peril – the spills and pollution – and the naked greed when rural farmers and retirees claimed that what looked once like a gold rush turned into a Big Con.

Most Pennsylvanians probably never heard of McClendon, or when he was covered – as news of his death was relayed today in the sports section of the Daily News – it was as part-owner of the NBA’s Oklahoma City Thunder. But even before his team started thumping our hapless 76ers, McClendon was quietly changing the path Pennsylvania’s politics. [Like Encana did to Canadian politics, via Harper?]

In 2004, the Oklahoman wrote $450,000 in checks to a nationwide Republican political action committee, or PAC, which then funneled the money to the GOP’s Pennsylvania attorney general candidate, Tom Corbett, which the bought the radio and TV ads that gave him a razor-thin victory — and a platform to become governor six years later. Corbett would repay the fracking industry many times over as governor — fighting successfully to keep Pennsylvania as the only major gas-producing state without a severance tax. [Is that what Rachel Notley is doing reducing royalties and making permanent the God-awful subsidies the Tories gave the oil and gas industry in Alberta?]

McClendon later insisted he didn’t know the money was going to Corbett, and his company had no business in Pennsylvania at that time. However, over the next few years, so-called “landmen” working on behalf of McClendon’s Chesapeake were working the rural communities on the state’s northern and western fringes, signing leases and promising big returns as new advances in drilling would now tap the gases deep in the Pennsylvania bedrock.

By the late 2000s, McClendon – whose Chesapeake was also a major driller in the American Southwest – was a billionaire. Pennsylvania was a major source of his wealth; in the late 2000s, one of every six drilling permits in Pennsylvania was issued to Chesapeake, and the firm had some 350 wells in the Keystone State. But the pressure to produce grew enormous.

Much of the pressure came from McClendon who — in the “There Will Be Blood” spirit of the oil patch — was a gambler by nature. His massive $1.9 billion share in Chesapeake was leveraged to the max, and when natural gas prices began to collapse — a predictable Economics 101 supply-and-demand result from all the gas now flowing from fracking pads across the United States — McClendon was in deep. But instead of paying the piper, he got the company’s board to boost his annual pay to $112 million, making him for a time the highest paid CEO in America. The board also spent $12 million to bail out McClendon by purchasing some of the rare maps he’d collected when the times were good.

Yet gas prices — and Chesapeake’s stock price — continued to fall, and many of the five-year leases that Chesapeake’s landmen had signed up were about to expire. The company’s drilling increased, and its environmental record went downhill. Pennsylvania regulators wrote up 428 violations against the company and fined it $1.4 million, and last November a unit owned by Chesapeake was hit with another $1.4 million fine for a 2011 landslide at a wellpad that polluted several streams in Greene County.

Also in 2011, Chesapeake workers were trying to close down a well in Avella, Pa., south of Pittsburgh, when “wet gas” that regulators say was being handled improperly burst into flames, causing five tanks to explode and injuring three workers. Residents saw an entire hillside on fire and thought that a C-130 cargo plane had crashed.

That same year, reporting on the company’s activities, I spoke to a Bradford County man named Ed Bidlack who told me that he and his neighbors had signed lease deals with Chesapeake’s landmen and had hoped to make good money from the fracking boom, but not long after a well was drilled next door, his own water turned funny — sometimes brown, sometimes fizzing like Alka-Seltzer. Chesapeake had given him a so-called “water buffalo” to replace his well water, but Bidlack still wondered whether the original tap water, tainted with methane, is what had caused his beagle Sid to quickly die from lymphoma.

Other Chesapeake leaseholders said they had a different problem with the now-cash-strapped Oklahoma company; they alleged the firm was cheating them out of royalties by claiming huge costs and then paying the Pennsylvanians next to nothing for the gas produced on their property. There are now several class-action suits against Chesapeake as well as a lawsuit by the state attorney general’s office.

Meanwhile, McClendon’s personal business practices came under increased scrutiny.In 2012, Reuters published an investigation that chronicled both the billionaire’s lavish lifestyle and business practices that critics said amounted to insider dealing; Wrote the news service:

From the 111-acre corporate campus that he shaped with a meticulous eye for detail, McClendon has intertwined his personal financial interests with those of the publicly traded corporation he runs to a far greater degree than shareholders may realize, according to interviews, public records and hundreds of pages of internal Chesapeake documents reviewed by Reuters.

McClendon, 52, has put longtime friends on the Chesapeake board and showered them with compensation. Restaurants he has co-owned occupy buildings owned by the energy company. A Chesapeake executive has handled the CEO’s personal land and oil- and gas-well transactions.

The piece also contains this now-chilling passage:

Beyond the mixing of personal and professional, another theme emerges from interviews and records: McClendon’s seemingly insatiable desire to own more and more — of everything. Said a contemporary who knows McClendon well, “If you’re competitive like Aubrey, you just always want to own more.”

But McClendon’s cycle of wealth and greed was already spiraling out of control by the time the Reuters article appeared. A subsequent report by Reuters about a hedge fund that McClendon was running on the side caused the Chesapeake board to force him out as CEO of the company that he’d founded and built. Earlier this year, Chesapeake said it was done drilling new wells in the Marcellus Shale.

This week, the spiral finally closed in. On Tuesday afternoon, McClendon was indicted by a federal grand jury for his alleged role in a long-running bid rigging scheme on oil-and-gas drilling in his home state of Oklahoma. On Wednesday morning, McClendon got in his black Chevy Tahoe and sped down a roadway in Oklahoma City, crossed the center median and crashed at a high rate of speed into a bridge embankment. The 56-year-old McClendon, who was not wearing a seatbelt, was killed instantly. Local police haven’t determined whether the crash was an accident or intentional, but a police captain said “he pretty much drove straight into the wall.” He’d been scheduled to turn himself in two hours later.

Whatever the cause, condolences are in order for the friends and family who loved him and lost him at such a young age. The story of his life and death played out as a 21st Century kind of Greek tragedy, his seeming brilliance as a business executive ultimately swallowed by his tragic flaw of hubris and the inevitable consequences of “always want(ing) to own more.”

In Pennsylvania, Aubrey McClendon is survived by a legacy mostly of conflict, of thick lawsuits, of protesters facing off against armed marshals, of lawmakers and a governor at war over the taxes that gas drillers never had to pay, of brackish water and leaking methane adding to the greenhouse gases that may someday strangle the planet — of a promise of buried treasure that wasn’t really all it was cracked up to be. [Emphasis added]

Maple syrup farmers lose fight against fracking pipeline by RT, February 21, 2016

A family of maple syrup farmers in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania cannot stop their trees being cut down to make way for a new fracking pipeline project owned by billion dollar oil companies, a federal judge ruled Friday.

The Holleran family opposes the seizure of their maple grove to make way for the new 124-mile-long Constitution Pipeline. [What when there is nothing left to eat or drink, but frac waste?]

The group faced contempt of court charges for obstructing tree cutting on their property.

The land is being taken by eminent domain to be turned into a 120ft wide passageway for the pipeline. The $875 million proposed project would carry gas from fracking sites in the northeastern Pennsylvania borough of Montrose into the capital of New York state, Albany.

On January 29, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) gave a partial notice to proceed with tree cutting on the 25 mile Pennsylvania side of the pipeline.

Companies backing the pipeline sought permission to cut trees along the New York side, but were blocked by environmental groups and state Attorney General Eric Schneiderman.

Those who oppose the pipeline argue Constitution is getting a jump on the project despite not having permits in New York and are calling for a stop to the tree cutting in Pennsylvania.

Lawyer Mike Ewall of Energy Justice Network said, “Constitution Pipeline Company is threatening this family’s livelihood for a pipeline that may never be built. They still don’t have FERC’s permission to construct, yet they bully and intimidate landowners while offering paltry compensation for taking their land.”

The defendants confronted tree cutters on their property on February 10. The contempt of court charges were dismissed when state trooper Monty Morgan was unable to identify the defendants.

The judge stood by his earlier decision to grant eminent domain to the pipeline company and said US marshals would be directed to arrest people interfering with the tree cutting.

This means the family has no right move the tree cutters off their land, despite their lack of consent and loss of livelihood.

Some 200 maple trees are to be cut, about 80 percent of the maple trees on the property. The family want to be fairly compensated for the loss of land, rather than stop the pipeline.

Family spokeswoman Megan Holleran said, “We know they’re allowed to cut down the trees, but we’re still hoping they may not. My family’s not going to do anything to violate the court order.”

Federal wildlife rules dictate that the company may only cut trees between November 1 and March 31 in order to protect migratory birds and the endangered long eared bat. If the deadline passes before the trees are cut, the company will be forced to wait until fall.

The pipeline is a partnership of $1 billion Texas company Cabot Oil; $12 billion Oklahoma company Williams; Piedmont Natural Gas, also from Texas; and the public utility holding company WGL serving the Washington DC area.

Cabot has a long history of spills and contaminated drinking water and killed fish with high levels of methane in the Dimock, Pennsylvania area in 2009, after up to 8,000 gallons of potentially-carcinogenic drilling fluids spilled from a well site.

In 2014, the Department of Environmental Protection fined Cabot $120,000 for a storage tank explosion and spill in Susquehanna County.

A Williams gas pipeline ruptured in Pennsylvania in January, forcing residents to evacuate.

The company had a major leak at a gas plant in Colorado in 2012. The leak was not revealed until 2013, when lethal levels of benzene levels were recorded, which had polluted the groundwater and soil.

The Transpacific Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) agreement could allow “private companies to sue governments for loss of profits connected to regulation” through “investor state dispute settlement”, according to the Guardian.

If it passes, families like the Hollerans will have even less power to resist the detrimental effects of oil and gas companies. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to: