Protection of drinking water – The province drops the town of Ristigouche Translation July 30, 2014 by Amie du Richelieu of Protection de l’eau potable – Québec laisse tomber Ristigouche, La municipalité gaspésienne est forcée de récolter des fonds pour se défendre contre la pétrolière Gastem by Alexandre Shields, July 29, 2014, LeDevoir

The Gaspésie Peninsula municipality is forced to collect funds to defend itself against the oil company Gastem.

The small municipality of Ristigouche Sud-Est, in the Gaspésie, keeps contacting directly the Minister of Municipal Affairs Pierre Moreau to get his help, but Le Devoir has learned that Quebec will not step in the case of the lawsuit initiated by the oil company Gastem. With no way to defend itself, the town has to have a funding campaign to pay for its legal fees.

“The Ministry is showing its ignorance when it comes to our situation, said François Boulay, Mayor of Ristigouche Sud-Est on Monday. It is offensive. Either they do not understand anything, or they are tuning us out.”

The Mayor did contact the Municipal Affairs Ministry many times. He finally wrote directly to Minister Pierre Moreau to ask to see him. “I ask the Minister to meet him so he can help me find a solution, explained Mr Boulay. I did not ask for money. I simply stated the facts and explained our situation.”

The situation is like this: Ristigouche Sud-Est was sued by Gastem in August 2013 because it passed a bylaw to protect drinking water, which had the effect of blocking exploration projects of the oil company. As per the wording of the motion filed in Superior Court, the Municipality “overstepped its authority by creating out of nowhere a nuisance by banning an exploration activity presenting no serious inconvenience and in no way susceptible of undermining in any way public health or the well being of the community”.

The company, whose president is the previous Liberal Raymond Savoie, is claiming $1,5 million to refund the investments it says went to a drilling project. It does not want to go on working in that area. It has even ceded its exploration permits to Petrolia.

Quebec says No

For the town of Ristigouche Sud-Est, the amount of money demanded is simply out of proportion. One has to know that the total budget for the municipality for fiscal year 2014 is $275,000. “We don’t even have the means to get us to the end of the lawsuit,” said François Boulay Monday.

Knowing about the fate of the municipality, Minister Morau refused to meet with the Mayor. “We have to tell you that the ministry cannot interfere in a question pertaining to a judicial procedure”, wrote the ministry in a short letter of which Le Devoir received a copy.

In a written answer sent Monday, the Ministry pointed out that it does not have a “programme to help municipalities caught up in legal lawsuits.” It added “interventions in financial aid affairs to help municipalities defend themselves while in court disputes are exceptional cases.”

The spokesperson for Minister Pierre Moreau did say that he is “aware of the plight of the citizens and the municipality in this case and will continue to closely follow the evolution of events.”

These answers are simply not enough for the Mayor of Ristigouche Sud-Est. He thinks there is no doubt that the government has its share of responsibility in this current dead-end. He thinks that Quebec has “waited too long” to pass the Regulation of water withdrawal and protection (RPEP), that came through last week. If it had been in place during the summer of 2012, he thinks that Gastem would not have received it’s drilling permit.

As for the Quebec municipality union, they have also refuse to comment on this subject Monday. “We shall look at this very closely”, simply answered the spokesperson Jules Chamberland-Lajoie. As for the Mutual of municipalities, the insurance company for Ristigouche Sud-Est, it refuses to pay for the defence costs of the municipality.

$225,000 must be found

In a real financial dead-end, the municipality has no choice but to launch a fund raising campaign to “deal with the Gastem lawsuit”, the Devoir has learned. The objective is $225,000. Many Mayors in Quebec must also jump at the occasion to bring their support to Mayor Boulay.

Some 70 Quebec municipalities have passed the bylaw called “de Saint-Bonaventure”. Many among them are in the St. Lawrence Valley and have done so to stop shale gas exploration and exploitation.

These municipal rules are as of now being replaced by the RPEP prepared by the Philippe Couillard government. For the first time, it determines the “minimum distance” that must be allowed between a drilling site and a drinking water source. It must be 500 meters. This distance could increase depending on the conclusions of the hydro-geological study that will be required by Quebec. [Emphasis added]

Ristigouche crowdfunds its defence in $1.5M gas company lawsuit, Ristigouche-Sud-Est in Gaspésie region sued for passing bylaw protecting water sources from drilling by CBC News, July 30, 2014

The Gaspésie village of Ristigouche-Sud-Est is being sued by Gastem, a Quebec-based oil and gas exploration and development company, for passing a bylaw in March 2013 establishing a two-kilometre no-drill zone near its municipal water sources. [Based on regulator and industry reports and data, it is unlikely that even a 2 km no drill zone will protect any community’s drinking water sources]

Now the town, which is home to 168 people, is facing a lawsuit five times its annual budget.

Gastem president Raymond Savoie said the passage of the bylaw was done without consulting the company. Savoie said the company has provincial government permits to drill in zones the village is trying to protect.

Ristigouche-Sud-Est mayor François Boulay launched a $225,000 fundraising campaign on Tuesday for its legal defence against Gastem.

The town set up a website to solicit online and mail-in donations. It has so far raised just under $15,000.

He said that the town has already spent more than a third of that on lawyers.

New rule came too late

Quebec’s Environment Minister David Heurtel last week brought in a new regulation on oil and gas drilling near waterways, establishing a 500-metre protected perimeter around potable water sources. More than 70 Quebec towns have adopted similar bylaws. “If Minister Heurtel’s rule from last week was in place at the time the gas company arrived [in Ristigouche], we would not be in the situation we are in today,” Boulay said.

However, Boulay said the Ministry of Municipal Affairs told him it would be inappropriate to get involved in the case because it is subject to a legal proceeding. [Is that an appropriate or accountable response for an elected official paid by the people, to serve the people?]

Municipal Affairs Minister Pierre Moreau told CBC/Radio-Canada he did not refuse to meet the mayor of Ristigouche-Sud-Est and said he was available to meet Boulay at the end of August to discuss the case. [Emphasis added]

Our Objective

Gastem’s objective is to create shareholder value through the exploration and development of high impact projects.

Our Strategy

Gastem’s strategy is to acquire, explore and develop new and prospective areas with a high level impact potential on a first mover basis. … Gastem’s main focus is to develop commercial production of the Utica Shale formations in Quebec and New York State as well as exploring the world class potential conventional structures of the Magdalen Islands and the Magdalen Basin in Quebec. Gastem was the first to target the Quebec Utica Shale formation when it drilled and cored two wells on the Yamaska permit in 2007. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to:

“These results, particularly in light of numerous contamination complaints and explosions nationally in areas with high concentrations of unconventional oil and gas development and the increased awareness of the role of methane in … climate change, should be cause for concern,” said the researchers in the paper.

Once an aquifer is contaminated, it may be unusable for weeks, decades, centuries or 10,000 years depending on the contaminant. (Some frack jobs in Alberta consist entirely of diesel fuel.)

Moreover groundwater contamination is an industrial curse that keeps on going. “Several studies have documented the migration of contaminants from disposal or spill sites to nearby lakes and rivers as this groundwater passes through the hydrologic cycle, but the processes are not as yet well understood.” As a consequence Environment Canada says that “preventing contamination in the first place is by far the most practical solution to the problem.” Any progress to date has been “hampered by a serious shortage of groundwater experts and a general lack of knowledge about how groundwater behaves.”

Despite documented cases of groundwater contamination throughout the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, no energy regulator has yet constructed a groundwater monitoring system to watch how oil and gas activity is changing the quality of groundwater over time.

…

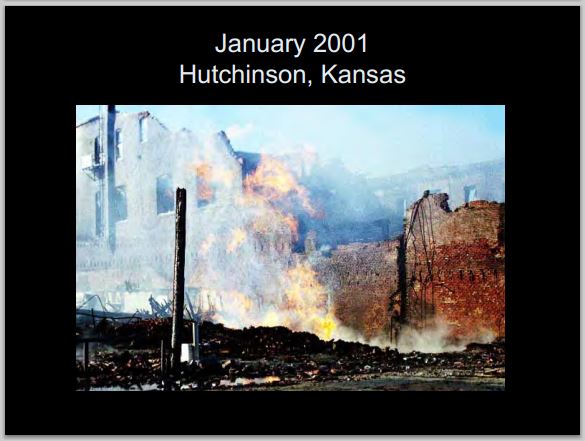

Next comes several damning cases involving the injection of hazardous fluids (including steam, acids and dirty water) into the ground. The evidence shows that they have a bad habit of moving along natural fractures and in unexpected ways. …

In Edmonton the oil and gas industry disposes of acid gas collected from the Redwater oilfield by blasting it, much like hydraulic fracturing fluid, deep into the ground. But this toxic gas is on the move: “After 13 years of injection, [carbon dioxide] has been detected at an offset producing well at 3,625 m distance in the same gas pool.”

In southern Alberta at the Retlaw-Mannville gas pool, sour gas travelled over two kilometres from an injection well to a gas producing well in less than nine months.

A federal report noted: “Several acid gas injection operations in Alberta have experienced unique reservoir behavior such as pressuring or acid gas breakthrough at offsetting wells.” …

At 62 facilities in Florida, three gigatons of wastewater injected into deep formations 1,000 metres below the surface was supposed to stay put. It didn’t: the dirty water migrated and contaminated drinking water.

None of this critical scientific data on the hazards of fluid and gas migration were addressed in any of the Canadian academic studies. [Emphasis added]