Film premiere outlines ‘devastating’ effects of fracking on rural communities by Meadhbh Monahan, June 6, 2013, Impartial Reporter

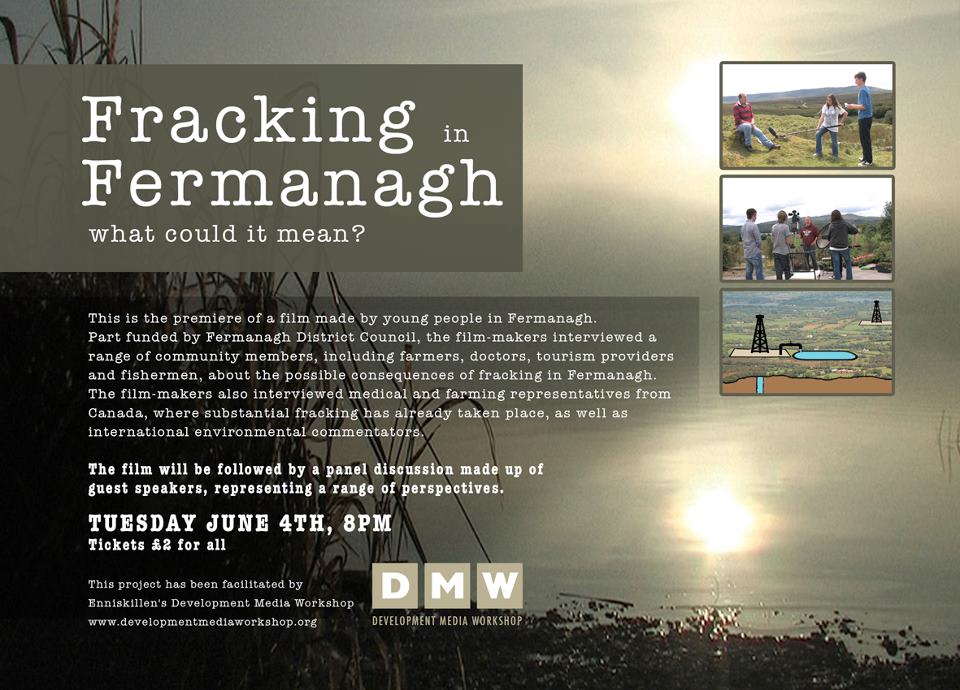

The division of rural communities is one of the worst effects of fracking, a Fermanagh audience heard on Tuesday night. In a new film called ‘Fracking in Fermanagh what could it mean?’, Canadian environmental scientist Jessica Ernst, who has experienced fracking near her farm in Alberta for the past 10 years, says: “I thought not being able to trust my drinking water was the worst affect of fracking but it’s the division of the community. The promise of money to some makes them obedient. I have witnessed heartbreaking betrayals on neighbours. Rural communities no longer take care of themselves as they used to. Whereas before they could fix the roof of their community centre themselves, now they are running to the company looking for money. There’s a loss of pride.” She also warns farmers of the “dire impact” of fracking, saying: “Be careful what you believe. Farmers in Alberta had to fight for the money they were promised.” In addition, farmers in Alberta were left liable for the gas mitigation from frack sites, meaning they could not use the land once the frackers left, but were still responsible for the clean up. This, and other stark messages were made in the film which was made by 15 local students (aged 9-22), facilitated by Enniskillen’s Development Media Workshop, and part-funded by Fermanagh District Council. It was dedicated to the memory of the late Josh Gallagher who had been involved with the film. The Ardhowen Theatre was sold out on Tuesday night with gasps and angry exclamations heard in reaction to what was shown on screen.

The film narrator explains that Enterprise Minister Arlene Foster was approached twice for an interview but declined. This was met by boos and shouting from the crowd. During a panel discussion after the film, Enniskillen actor Ciarán McMenamin said: “It’s good to see that our young people have our interests at heart, even if our politicians do not.” Fermanagh South Tyrone MP Michelle Gildrenew stated that “Sinn Féin will use every legislative measure available north and south of the border to stop Fracking.” She added: “Fracking will turn Fermanagh into an absolute sh**ehole.” The young film-makers interviewed farmers, fishermen, tourism providers, ecologists, doctors, young people and politicians. International perspectives on fracking were given by Jessica Ernst and Dr Eilish Cleary, Chief Medical Officer for Health, New Brunswick, Canada, both of whom have spoken at public events in Fermanagh earlier this year. The majority of Fermanagh folk are not aware of the magnitude of what fracking involves, the audience heard. Tamboran Resources plans to create 60 fracking pads in Fermanagh (each pad will be about seven acres in size, and concreted), one mile apart, covering 40,000 acres. “This will have a terribly detrimental affect” on Fermanagh changing it from a scenic, rural area into a heavily industrialised zone dotted with frack pads, the audience heard.

During the film, local farmer John Sheridan, who lives in the shadow of Cuilcagh mountain, says that chemicals brought up from deep underground during the fracking process are very likely to spill into our ground water, thereby leaking into our lakes and rivers and subsequently into our food chain. These chemicals could also evaporate from ponds on the frack sites, causing air pollution. He is backed up by Jessica Ernst who says: “They are bringing up unknowns that have been locked underground for millennia,” including naturally occurring heavy metals and radioactive materials such as arsenic, cadmium, chromium, thorium and uranium (all carcinogens which can cause cancer and respiratory diseases in humans). Air may also be contaminated by volatile chemicals released during drilling (combustion from machinery and transport) and from other operations, during methane separation or by evaporation from holding ponds, Jessica Ernst points out. John Sheridan concludes: “Farming or fracking; it’s going to be one or the other.”

A major problem is fracking waste, the film continues. This wastewater not only contains the toxic and hazardous chemicals used in fracking fluid but also contains contaminants that it picks up from deep within the earth, most notably heavy metals, volatile organic compounds, salty brine and radioactive materials. “In Alberta, money was given to farmers to spread this waste on their land,” Jessica Ernst says. Photos of this waste spreading process were met by gasps of shock by the audience. “What becomes of the drilling waste is a big hole in the story that fracking companies are not telling us,” she states.

Belcoo father-of-five Sean Sweeney tells film-makers that he needs to feed his family so he was initially happy to hear of the potential fracking jobs coming to Fermanagh. However, after researching the process, he says: “No way. These people are dealing with toxic waste and chemicals. Why would I expose myself and my family to that?” He says if Fermanagh allows Tamboran to frack, locals will have ruined the landscape for future generations and will have noone to blame but themselves. He received laughs and applause when he quipped that the new Ulster Way brochures would have to state: “Here’s your gas mask, mind the lorries and enjoy your walk!”

Terry McGovern Chairman of the Lough Melvin Anglers Association is worried about copious amounts of water being taken from Lough Melvin and then pumped back in. “What state is it going to be in?” He worries that the approximate 700-800 jobs in the local fishing industry could be jeopardised if fracking gets the go-ahead. Local caver Tim Fogg takes viewers to St. Patrick’s Holy Well in Belcoo where water rises from an underground spring at 45 litres per second. He points out that very little is known about where these springs originate, adding: “It doesn’t add up that you can just move into the area and drill without knowledge of the hydrology of the area.” [Emphasis added]