Le citoyen Encana – Le double visage de la plus importante corporation de Calgary Translation by Amie du Richelieu, August 21, 2013

Citizen EnCana The double life of Calgary’s greatest corporation by Adrian Morrow, published in Fast Forward, July 10, 2008.

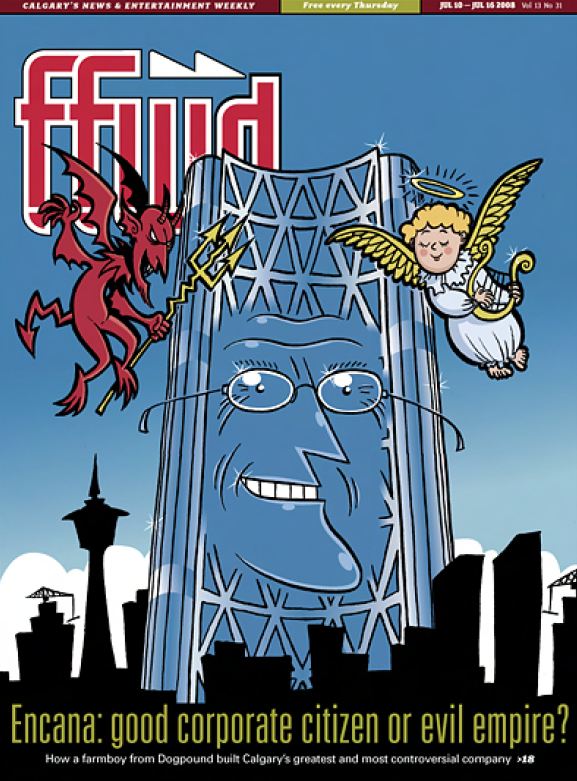

Source: Cover Fast Forward Weekly, Encana Bow Building & CEO Gwyn Morgan

Source: Cover Fast Forward Weekly, Encana Bow Building & CEO Gwyn Morgan

Jessica Ernst has so much natural gas in her water she can set it on fire. Photos above and below by Wil Andruschak [Photo later used by National Geographic May 10, 2011]

On a rainy spring night in 2006, Darrell Graff was birthing a cow when the gas came rolling in. EnCana was venting a well. The 30-year-old farmer started to stiffen up and soon he couldn’t move his legs. He shouted to his mom, Barbara. From the light of her flashlight, she could tell he was having a seizure.

Her own hands stiffening, the petite, 57-year-old Barbara slid through the mud, grabbed her son and loaded him into a truck. She had to drive several kilometres away from their farm before Darrell’s seizure subsided.

Both Darrell and Barbara are extremely sensitive to chemicals. Darrell’s case is so severe that emissions from natural gas wells can cause partial motor seizures and, on one occasion, nearly gave him a heart attack. The Graffs have told the natural gas companies, including EnCana, to either stop releasing gas off their wells or at least give them enough warning so they can evacuate their farm. So far, they say they’ve had little success. “This is life-threatening,” says Barbara. “EnCana seems to think they are above the law.”

The family has farmed the country near Vulcan, Alberta for five generations, and they’re reluctant to leave the only community they’ve known. Though, in recent years, gas development has become almost as important to the 2,000-strong town as agriculture.

The Graffs and the Vulcan area are the perfect metaphor for the two sides of EnCana Corporation. Canada’s largest energy company has created jobs, brought investment and poured money into rural communities across the Canadian Prairies and the western United States. It has also left a trail of farmers and ranchers who say the company has ruined their land, made them sick and killed their livestock.

Formed in 2002 by a merger of two smaller companies, EnCana has used a daring business strategy to put itself at the cutting edge of the oil and gas industry. It is one of the country’s most profitable corporations, with $23 billion in revenue last year, and the second-largest natural gas company in the world.

EnCana has made its mark everywhere it operates. This year, it plans to donate $35 million to charities in communities from northern B.C. to Texas. Everything from the 4-H Club — the iconic prairie club that teaches kids farming skills — to community rodeos have benefited from the company’s philanthropy. In Calgary, EnCana is building a billion-dollar skyscraper whose design has garnered praise from architecture critics. When finished, the 58-storey Bow will be Canada’s tallest building west of Toronto.

However, not everyone is happy with the company. Farmers have accused EnCana of contaminating their land with natural gas. The company’s money helped fuel a deadly fight in the South American rainforest between peasants and a government determined to build a pipeline through a nature preserve. And two Alberta ranchers have spent over a year fighting EnCana in court for nothing more than a basic guarantee that the company won’t poison their water. Some of these problems are well-known, others are reported here for the first time.

EnCana is a symbol of the West. Independent and proud, the company has defied government control and exploded the idea that only an American or European energy company can rate on an international scale. For the first time, Fast Forward tells the full story of Canada’s greatest business success, and the angry people left in its wake.

BIRTH OF A PRAIRIE GIANT

Every day when he was a kid, Gwyn Morgan would get up early to feed the livestock on the family farm at Dogpound, a stretch of desolate prairie 80 kilometres northwest of Calgary. The man who would go on to lead Canada’s largest oil and gas company didn’t have access to running water until he was 12. The youngest of four children, his tough upbringing left him with the belief that you could achieve anything you wanted if you worked for it. Those who didn’t succeed, he would come to believe, weren’t trying hard enough.

Morgan left home in his late teens to study engineering at the University of Alberta. Over the next few years, he explored the Arctic for oil with Norlands Petroleum before landing a job at Alberta Energy Corporation (AEC) in 1975.

The provincial government created AEC to put Alberta’s oil, gas and mineral wealth to work for its people. Shares in the company were sold to Alberta’s citizens. The government also handed AEC two key assets: a stake in the Syncrude consortium that was just starting to mine the oilsands near Fort McMurray, and the right to drill in the Suffield area north of Medicine Hat.

As the company grew, Morgan’s star rose. He set up the company’s operations at Suffield and later became head of the company’s oil and gas division. In 1994, the year after the province privatized the company, Morgan was promoted to CEO. A nationalist, his dream was to create a Canadian-owned oil and gas company that could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the international giants.

“He’s a very determined, smart guy,” says Dick Haskayne, a veteran oilman and former AEC board member. “He knows engineering, and he knows the oil business, but he has a broader outlook on life and is very good at making judgments on political implications… whether it’s the environment or finance.”

Morgan doesn’t fit the stereotype of an oil baron. He speaks with a clear diction, eats health foods and works out for 90 minutes a day. He has a slim physique, a rim of white hair surrounding his balding head, and sports a pair of small round glasses. His hard childhood left him with a strong work ethic that made him a tough CEO. In the 1990s, he engineered a series of hostile takeovers of smaller companies, giving AEC vast reserves of natural gas in Alberta, Wyoming and Montana, as well as a lucrative oilfield in Ecuador.

Morgan eventually set his sights on the biggest prize of all: the reserves of Canadian Pacific (CP). In 1880, the federal government gave CP 100,000 square kilometres of land to build the railway, as well as the right to extract the coal and natural gas under its surface. In 2001, the government set these oil and gas resources aside as a private company called PanCanadian Energy. That October, Morgan called CP chairman David O’Brien, telling him he wanted to discuss about merging AEC and PanCanadian. At Haskayne’s urging, O’Brien agreed to talk.

A few days later, he and Morgan began secretly negotiating the merger of their companies. At first, they met alone in CP’s vacant offices on the 18th floor of Bankers Hall. In January 2002, when the two men brought their high-level staff into the discussions, they moved the meetings to rented rooms at Calgary’s downtown Hyatt, a few blocks away. Haskayne recalls that Morgan kept the discussions low-key by disguising himself in jeans and carrying a backpack when he showed up at the hotel. Secrecy was crucial: if anyone found out that AEC and PanCanadian were negotiating a merger, the companies could become targets for hostile takeovers.

For three months, the talks were kept under wraps. On Sunday, January 28, Morgan and O’Brien finally made the deal public. Morgan would lead the new corporation, while O’Brien would take the honorary role of chairman. Always the patriot, Morgan named the company EnCana, a shortened version of “Energy Canada.”

The new company adopted an unconventional business strategy. Rather than look for new sources of oil and gas overseas, EnCana focused on its core business in North America. Thanks to the resources the Canadian and Alberta governments had granted PanCanadian and AEC, EnCana controlled vast gas fields in southern Alberta. Most of the conventional natural gas was already tapped out. The company, however, realized that with the right technology, it could extract gas from the rocks around the depleted gas deposits. The technology is called hydrolic fracturing, or “fracing” (pronounced “fracking.”) It entails shooting high-pressure gas or water into the ground to smash open the rock and release the gas. The technology worked, and soon old fields were producing mass quantities of gas again.

Meanwhile, the company’s investment in Ecuador was causing it headaches. EnCana tried to clean up oil spills in the country left by previous companies and funded a local NGO to help farmers sow their fields more effectively. However, the company soon ran into trouble when it bought a stake in a project to build an 800-kilometre-long pipeline project intended to transport crude oil from the company’s wells in Ecuador’s eastern jungle to the sea. The pipe was routed through a nature preserve and faced opposition from farmers and villagers along the way.

On one occasion, residents of El Reventador, a village on the route of the pipeline, barricaded roads outside of town with flaming tires. After police moved in and two protestors were killed, the blockade was lifted. “To construct that pipeline there was a lot of coercion,” says Nadja Drost, a Toronto filmmaker who documented the building of the pipe. “It was not a very free environment.”

Workers on the new pipeline also ruptured an old pipe and spilled 1.6 million litres of oil into the river that supplies Quito, Ecuador’s capital, with water.

In 2005, Morgan sold off EnCana’s holdings in Ecuador to a consortium of Chinese companies as part of his strategy of divesting the company of conventional oil and gas to focus on fracing natural gas wells in North America. The daring strategy, which some of Morgan’s fellow CEOs had doubted, was paying huge dividends. The company’s profits had jumped more than 65 per cent in a single year to $5 billion.

“EnCana had a head start with the PanCanadian lands,” says Bob Schulz, an oil and gas expert at the University of Calgary. He also credits EnCana’s modern corporate culture with the company’s success. For instance, the company chose its management from among its personnel in the field, so EnCana’s leadership understood what was happening on the ground.

The company’s corporate culture was also sensitive to public opinion and responsive to environmental concerns. EnCana made a point of meeting with environmental groups and landowners to discuss problems. Not to mention the company’s philanthropy: company policy is to donate a percentage of net revenue to charities and other worthy causes.

In October of 2005, Morgan retired as CEO and turned over the job to his second-in-command, Randy Eresman. Like Morgan, the Medicine Hat-born Eresman started with the company as an engineer and worked his way up. He was a key organizer during the merger, integrating the company’s engineering operations and auditing PanCanadian’s assets.

Unlike Morgan, however, he spurns the spotlight. “He’s a very down-to-earth, small-town guy, if you will. He’s very technically competent, people trusted him,” says Haskayne.

In December 2005, Morgan gave the most famous speech of his career. At a meeting of the Fraser Institute, a neo-liberal think-tank, the Canadian patriot laid out his vision for the country. He expounded on the merits of lower taxes, a privatized health-care system and a do-it-yourself attitude. He had built his company on assets donated by the government, but his message to the public sector was clear: stay out of business’s way.

“There are still many Canadians who fail to grasp that, ultimately, the success of any society is dependent upon those who try harder achieving better rewards than those who don’t,” he told his audience. Morgan was living proof of his own ideology. If a farm boy from Dogpound could rise to become one of the country’s most powerful CEOs, couldn’t anyone?

FROM ROSEBUD TO RIFLE

The village of Rosebud sits among poplar trees in a lush valley, an oasis on the endless plains east of Calgary. Best known for its performing arts college and brightly painted frontier buildings, the community of 100 people is surrounded by EnCana’s wells, and the loud, buzzing noise of well maintenance is a common sound.

Jessica Ernst lives on an acreage a five-minute walk from town. The environmental consultant was working for EnCana in the summer of 2003 when the company built a compressor station on the bluffs less than a kilometre from her house. The station, which takes gas from the ground and compresses it into a liquid that can be easily shipped, emits loud, grinding, mechanical noises that keep Ernst up at night.

Like Morgan, the 50-year-old Ernst has a tough personality that puts her at home among the independent-minded farmers and ranchers of Alberta. When the noise started at the compressor station, she refused to keep quiet.

She unsuccessfully pressured the company to stop the noise. She also pushed it to consult with the community. By her account, EnCana’s agent showed her a legal agreement it hoped to get landowners to sign, which would release the company from liability. “If we can get them to sign this, we don’t need to consult,” he said. Ernst quit the company.

When EnCana did start consultations, there was little landowners could do. Landowners only own the surface of their land. Everything underneath — minerals, oil and natural gas — belongs to the province, which can sell it to private companies. When a company wants to drill a well to access the gas, it has to make a deal with the landowner to lease part of their land to build the well on. If they can’t reach an agreement, the company can take the landowner to the Surface Rights Board (SRB) or the Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB), two quasi-judicial provincial bodies. Once a hearing into the case has been conducted, they can order the landowner to let the company in, or order the company to fulfil certain conditions before drilling.

In 2005, Ernst noticed something was happening to the water from her well. At first, her dogs wouldn’t drink it. Then, she saw it was fizzing as if it was carbonated. In December, she couldn’t turn her taps off: there was so much gas in her water, it raised the pressure and forced its way through her pipes.

She also discovered she could light it on fire. When lit, a huge blue flame burns on the surface of the water, before turning orange and escaping upward like a flare. “It still scares me,” she says. “You never know what the water is going to do.”

Tests on her water revealed high levels of methane, ethane and several other fossil fuels. It also showed signs of heavy hydrocarbons, like the ones used in drilling fluids. Three other area wells have shown high levels of gas. At least two studies have shown that, when a well is fraced, the pressure can break through the bedrock and leak natural gas into the groundwater. Drilling fluids can also contain trace amounts of chemicals, ranging from diesel to ammonium.

EnCana, however, denied that its fracing had contaminated Rosebud’s water supply. Earlier this year, a provincial report on Ernst’s well concluded that the gas in the well was naturally occurring and had nothing to do with the company.

Ernst has doubts. A company report from 2005, for instance, shows that EnCana fraced the underground aquifer where area landowners get their water. A test by University of Alberta water expert Karlis Muehlenbachs also showed strong similarities between the gas in Ernst’s well and the gas EnCana was pumping out of the ground nearby.

Two hundred kilometres away, Shawn and Ronalie Campbell were having similar problems. In 1999, a pipeline belonging to PanCanadian, one of EnCana’s forerunners, corroded under their land and spilled saltwater onto a hectare of their farm near Ponoka. Contractors have started to remediate the land, but, nine years later, the Campbells say the grass in the area of the spill is stunted. In the summer of 2005, one of the Campbells’ water wells went dry. When they replaced it with a new well, the water bubbled and spurted out of the tap. Testing indicated the presence of natural gas in the water supply: methane, ethane, propane and iso-butane.

Jeff Locker and Louis Meeks, farmers near Pavillion, Wyoming, have seen their water go bad in the wake of EnCana fracing in the area. Locker’s water even turned black. In 2004, he says EnCana paid him $21,000 US in exchange for agreeing not to talk about what had happened. The following year, EnCana drilled another well to the west of his place and his water turned black again, so he decided to break his silence.

Meeks says EnCana has offered to buy him out, but hasn’t set a price for his property. “I’ve told them to make me an offer I can’t refuse,” he says. “How do you put a price on 30 years?”

Further south, in the area around Rifle, Colorado, EnCana leaked natural gas and benzene, a carcinogenic chemical, into a creek, and paid a $371,200 fine in 2004. The following year, a group of area landowners sued EnCana, alleging the company hadn’t paid them what it owed in royalties. The company has agreed to pay $40 million to settle the suit.

In line with the independent, anti-government politics of its founding CEO, EnCana also never bothered applying for a drilling license from the local government in Rifle for four years. EnCana owed over $100 million in unpaid fines, and agreed to pay $15,000 to the municipality earlier this year. The company has also been trying to stop the Colorado government from imposing stricter environmental regulations by threatening to pull out of the area, and encouraging the charities it donates to to apply pressure on the government as well.

Back in Canada, the company has fought with the federal government over its drilling rights in the Suffield area north of Medicine Hat — one of the last stretches of native prairie left in Canada. The government has investigated EnCana for allegedly building a pipeline and several roads on the preserve without permission. In 2007, a company pipeline burst in the area and spilled 50,000 litres of oil and saltwater under a wetland.

Fast Forward spoke with 20 farmers and ranchers while preparing this story, and the same concerns came up frequently: some were afraid the company was contaminating their water; some accused the company of allowing weeds to grow on their leases, endangering their crops; almost everyone said the company wasn’t taking their concerns seriously. All these complaints pale next to the health problems experienced by a few of the landowners who’ve crossed paths with EnCana.

Laura Amos, a farmer in the Rifle area, became sick with a rare adrenal gland tumor in 2003 after EnCana fraced wells in the area. One of the drilling chemicals the company’s contractor might have used, 2-BE, has been linked to adrenal gland tumors. Chris Mobaldi had two tumors on her pituitary gland, something she alleges could be linked to air and water pollution from EnCana’s gas activity. The company, however, denies responsibility. It says its contractors never used 2-BE in their fracing operations.

Barbara and Darrell Graff, the mother and son who farm near Vulcan, first noticed their chemical sensitivity in 1998 when Darrell nearly collapsed in his field during a well flaring by a different company. In 2000, the family, which includes Darrell’s father Larry and sister Anita, moved from their original farm east of Vulcan to a smaller parcel west of town to escape the fumes. Four years later, EnCana started drilling near their new place. The Graffs told the company about their condition and asked that the company inform them when they were planning to flare so the family could evacuate. “When they initially came into this clean area, we gave them our medical evidence,” Barbara says. “Very seldom have they given us notice. I can’t understand this.” They say the farm has also lost several cows since the gas activity came to the area. (EnCana’s lawyer insists the company’s operations in the area have no negative impact on the Graffs.)

At first glance, Darrell seems like a typical southern Alberta farmer, with a deep tan, a rugged brown beard and a friendly demeanour. However, his symptoms are so bad, he walks with a cane, and he’s unable to perform most of the tasks he could before he became sick. Virtually all he can do is tend the cows.

Kaye Kilburn, a Los Angeles-based neurologist who has examined the Graffs, believes poisoning from hydrogen sulfide gas is to blame for Barbara and Darrell’s condition. He says the substance is harmful in as small a concentration as one part per million, and argues it is worse than chlorine or the nerve gases used in the First World War. “If it doesn’t kill you, it produces brain damage,” he says. “It’s a first-class poison.”

A NEW TYPE OF COMPANY

The gate springs open and a cowboy gallops into the ring. Ahead of him is a lean, brown bull, running just a few steps in front of the horse. As he catches up, the cowboy dives off his mount and grabs the steer’s horns in his hands. He twists the animal’s head to the side and drags it down to the brown dirt of the arena floor, then pulls its body around until the bull is lying on its back, its legs in the air.

This is Canada Day in Ponoka. A good chunk of the town’s 6,000 people have crammed into the bleachers to watch the rodeo finals. The sun is baking the cowboys sitting on their horses and waiting for their turn to wrestle steers in the ring, kids meander through the stands selling drinks, and fertile green hills dotted with crops stretch beyond the arena.

Agriculture, of course, isn’t the only game in town. Oil and gas are just as important to this area’s economy, and the industry has made its presence known. EnCana’s black, white and green signs line the side of the arena. An EnCana banner hangs overtop the gate at one end of the ring. When the announcer takes a break from the rodeo to thank the event’s sponsors, a blond girl on a grey horse gallops past the spectators, waving an EnCana flag.

Ronalie and Shawn Campbell, farmers whose water well was contaminated with natural gas, have come to town for the show. After years of trying to hold gas companies accountable, they’ve won a crucial court battle with EnCana that could change the way the company operates.

It started in February 2006, when EnCana took over a gas well on the Campbells’ land from another company. They asked EnCana to sign a lease with several protections: among others, the company would insulate the well to stop gas from travelling through the ground and contaminating the drinking water, and monitor the water for contamination. The company refused.

In July 2007, EnCana took the matter to the SRB, hoping to be granted the right to frac without fulfilling the conditions in the lease. At a hearing in Ponoka, company lawyers questioned the Campbells for three hours. “We were cross-examined on everything under the sun,” says Ronalie. “They were asking ‘what was the basis for the water testing?’” Shawn felt pummelled by EnCana’s questioning, and thought they didn’t stand a chance.

In November 2007, the SRB issued a ruling. To the Campbells’ surprise, they won. EnCana would have the right to use the well, but only if the company followed the conditions in the lease. However, the company wasn’t ready to give in. It appealed the decision to the Court of Queen’s Bench, and the case went to trial April 9 in Edmonton. Again, the judge ruled in the Campbells’ favour. For the first time in Alberta, a court required EnCana to protect a farmer’s groundwater.

The company itself is experiencing a flurry of activity these days. On May 11, it announced it would split in two. Its natural gas holdings, which represent roughly two-thirds of the company’s assets, will become one company led by EnCana CEO Randy Eresman. The company’s oilsands projects will form a second, smaller company. The plan is to allow each of the company’s two divisions to focus on its own operations.

At first glance, the split seems like a repudiation of what Gwyn Morgan created the company to be: the only Canadian oil and gas company to rival the size of their American and European competitors. Industry observers say otherwise. Breaking EnCana into two entities will likely make each company a safer investment, the gas company will still be the world’s second-largest and Morgan’s dream won’t disappear.

An iconoclast, his unusual business strategy worked for the company. So, too, have some of its attempts to be more environmentally and socially conscious. In response to public concern over flaring, for instance, EnCana drastically cut its use of the practice. “They’ve really created a new type of company, sensitive to stakeholders,” says Keith Brownsey, a professor at Calgary’s Mount Royal College. “Much of the industry has taken their lead from EnCana.”

Not everyone agrees, however. Darrell and Barbara Graff’s health problems are so bad, they had to evacuate their home last week to avoid the gas. As of press time, they are living in their van. Larry is less affected than his son and his wife, and is trying to maintain their farm as best he can. Fighting a company that employs so many people in a small community isn’t easy, and fellow landowners are reluctant to speak up. As he points out the well that he believes is responsible for forcing his family from their land, a group of coverall-clad men gather on the platform and stare back at him across a sweet-smelling, yellow field of canola.

The view is not unlike the landscape at Dogpound, where the most successful man in Canada’s energy industry once eked out a living. Mountains stand in the west, green fields of barley and hay meet the dusty prairie sky at the curve of the earth, and heatwaves rise like gas from the ground.