Study maps fracking methane risk to drinking water by David Shukman, Science editor, July 3, 2014, BBC News

A major study into the potential of fracking to contaminate drinking water with methane has been published. The British Geological Survey and the Environment Agency have mapped where key aquifers in England and Wales coincide with locations of shale. The research reveals this occurs under nearly half of the area containing the principal natural stores of water. The risk of methane being released into drinking water has long been one of the most sensitive questions over fracking.

The study highlights where the rock layers may be too close to the aquifers for fracking to go ahead. It finds that the Bowland Shale in northern England – the first to be investigated for shale gas potential – runs below no fewer than six major aquifers. However, the study also says that almost all of this geological formation – 92% of it – is at least 800m below the water-bearing rocks. Industry officials have always argued that a separation of that size between a shale layer and an aquifer should make any contamination virtually impossible. They say that wells are sealed with steel and concrete as they pass through water-bearing rocks and that any fissures created by fracking far below would be highly unlikely to spread through hundreds of metres of rock.

…

Analysis of the Weald Basin in southern England shows that the uppermost layer of oil-bearing shale is at least 650m below a major aquifer.

Dr John Bloomfield, of the British Geological Survey, said the maps could serve as a guide for regulators and planners. “We’ve identified areas where aquifers are in relatively close proximity to shale units and any developments would have to be looked at particularly carefully,” he said. “It’s no surprise that the same system of sedimentation that produces shale also produces limestone which is excellent for storing water.”

Ruled off-limits

Aquifers such as the Oolite, which runs from Yorkshire through the East Midlands to the south coast of England, are often in direct contact with a shale layer. Interactive maps showing the relative proximity of shale layers and aquifers are available on the British Geological Survey website.

So far, no definitive distance for separation between shale and aquifers has been set but a limit of 400m has been suggested because water from below that depth is rarely considered drinkable. In some areas, shale layers rise closer to the surface – and the assumption is that these would be ruled off-limits. The Environment Agency says it will not allow developments to go ahead if they are too close to supplies of drinking water.

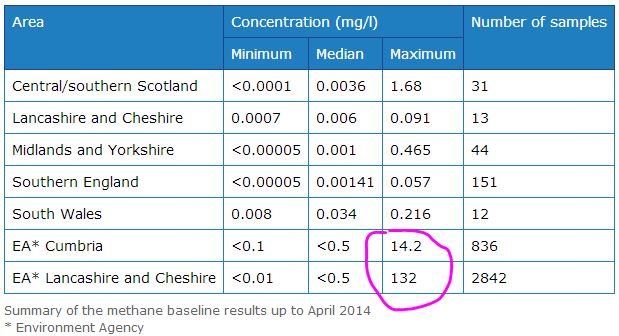

Meanwhile, the BGS has carried out a survey of methane in drinking water in all areas of the country where fracking may happen.

Low levels of the gas occur either naturally – from bacterial activity – or from manmade sources such as landfill sites. Dr Rob Ward, director of groundwater science at the BGS, said the aim was to provide a baseline understanding before any fracking starts. “In the United States, they didn’t carry out a baseline survey before the industry took place and that has resulted in controversy and uncertainty about the source of methane in drinking water,” he said. “We now have a window of opportunity to collect data on methane before any industry goes ahead. If we see increases in methane in groundwater which may be attributed to shale gas, we’ll be able to spot those.” [Emphasis added]

National Methane Baseline Survey: results summary by British Geological Survey, April 2014

Since the beginning of the National Methane Baseline Survey in 2012, a total of 82 new groundwater methane samples have been collected and analysed from four areas: South Wales, Midlands and Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cheshire and Southern England comprising Kent, East and West Sussex, Surrey and Hampshire. …

Methane baseline samples have been collected from potable water supplies — either drinking water or groundwater quality monitoring boreholes. None of the samples in the aquifers used for public water supply have exceeded the explosive limit [7-10 mg/l “watchful waiting” level] for methane. [Emphasis added]

Thousands of people have voiced their objections to plans to drill for shale gas on the Fylde coast July 3, 2014, Blackpool Gazette

Plans for a major Fylde coast fracking site have been given the thumbs down by thousands of residents, according to a campaign group. Friends of the Earth said more than 3,500 people had submitted objections over Cuadrilla’s proposals for the site off Preston New Road near Little Plumpton. The group said a further 1,500 letters of objections had been gathered by the Frack Free Lancashire campaign, which they intend to submit to Lancashire County Council this week.

Helen Rimmer, of Friends of the Earth, said thousands of people had submitted emails from a template on their website, with their own details and objections. She added: “People in Lancashire and across the UK are sending a clear message that Cuadrilla’s fracking plans are strongly opposed on environmental and community impact grounds. “The applications to frack multiple wells in the Fylde are of national interest as the area is nationally important for food production and wildlife protection, and what happens here will affect the future of the fracking industry across the country.”

Last month the shale gas company submitted a planning application for permission to drill, frack and test gas flow at up to four wells at Roseacre Wood near Kirkham. The documents are now open to public scrutiny. It followed a similar bid at Preston New Road and both include an environmental impact assessment from consultants Arup. County Hall bosses said they couldn’t confirm an official figure for residents’ objections as not all had been recorded.

…

Cuadrilla declined to comment until an official number was confirmed. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to:

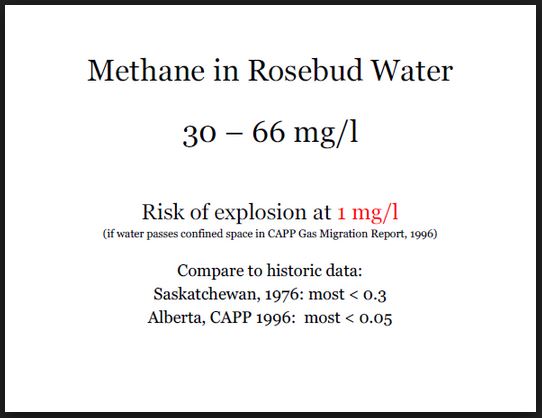

Slide from Ernst presentations

Slide from Ernst presentations

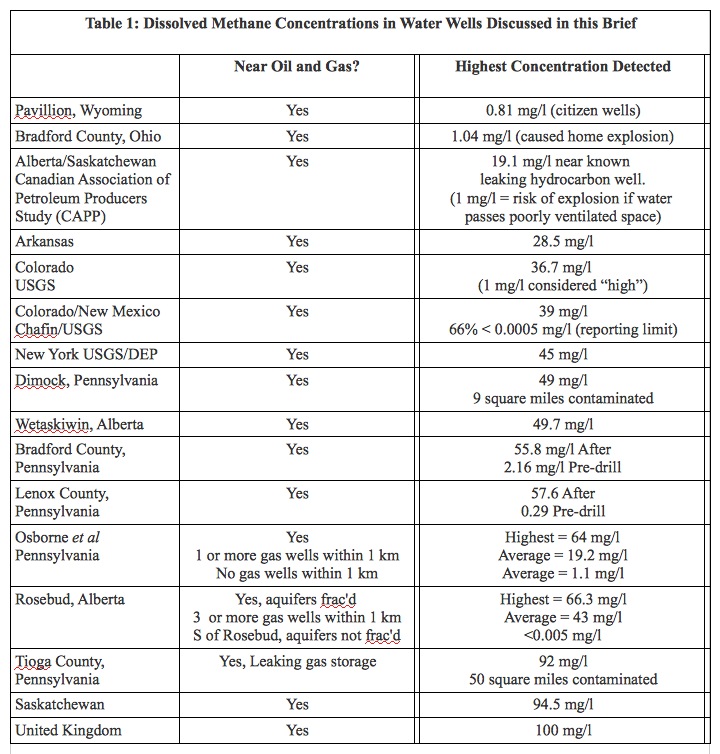

Table from Ernst 2013 brief on industry’s gas migration