I’ll never get over how hideous our species is.

The global patriarchal legal-judicial-religious industry (most especially in Canada) proves it again and again, letting rapists and abusers/murderers (including police) of women and kids off again and again, protecting them and giving them easy access to kids (self regulators of lawyers and judges are the worst) while blaming, shaming, brutalizing and revictimizing the victims. Human hideousness, enabled by the masses. Let’s all blame Eve.

“If only things had happened this way.”

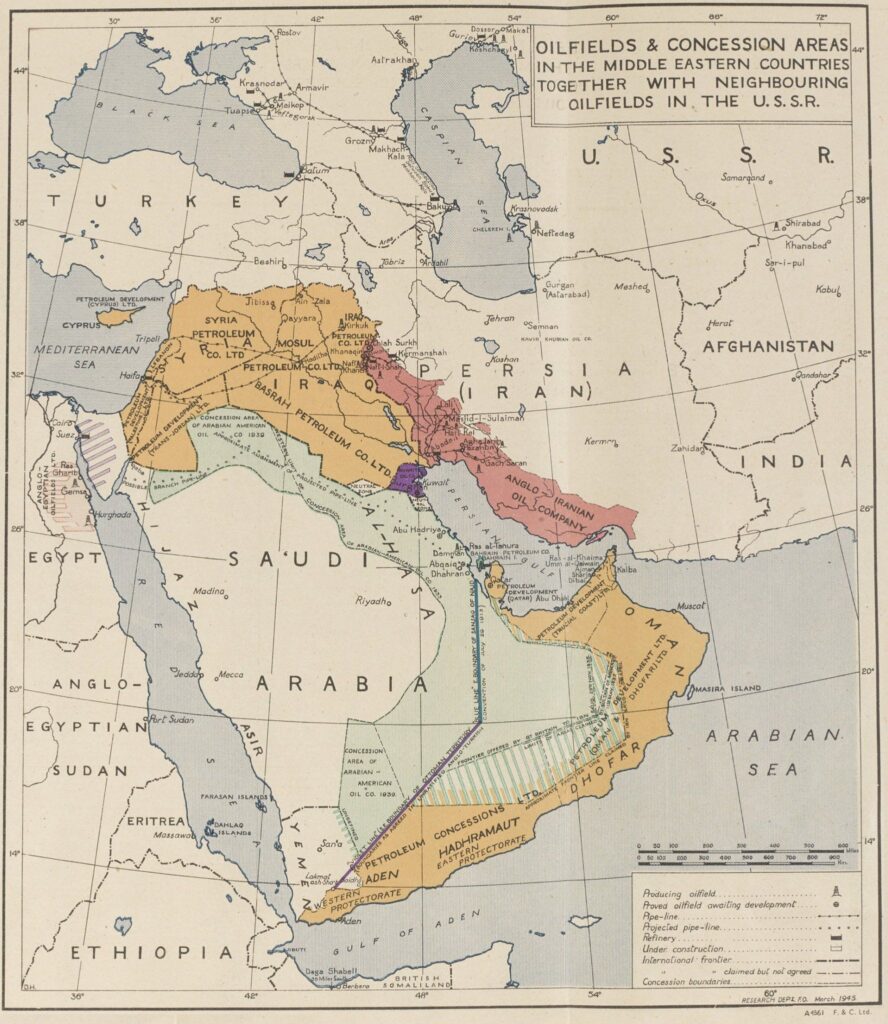

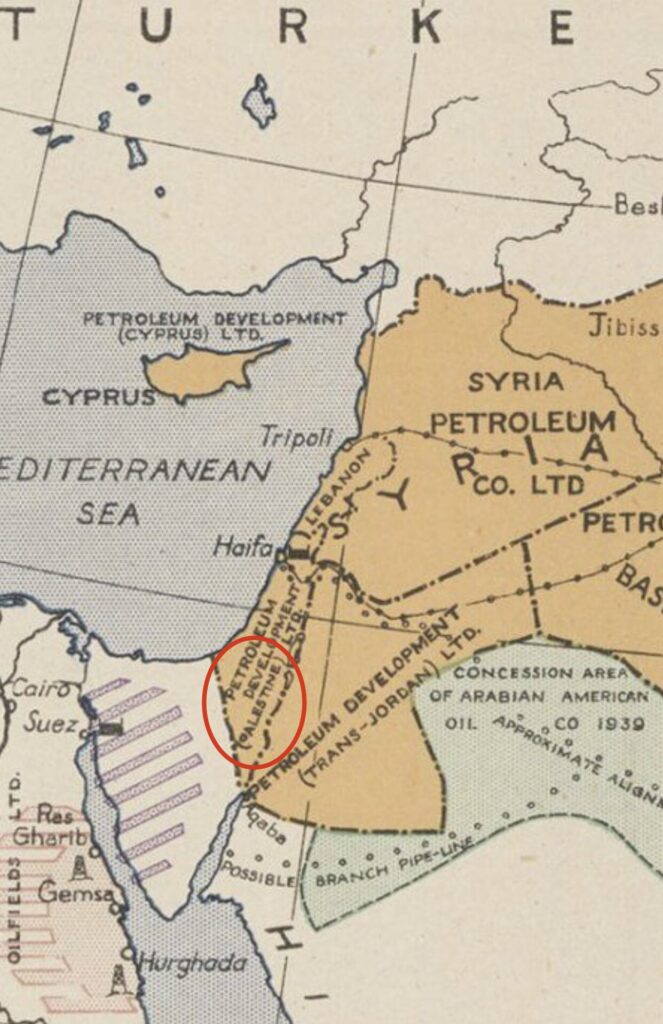

The global system of enablers (“regulators” and “law” makers) of weapons industries’ and fanatical movements like Zionism’s profit by genocide, propaganda, theft of oil and gas fields, and fossil fuel polluters’ (frac’ers are the worst) destruction of earth’s livability also proves it.

1945: Oilfield and Concession Areas in the Middle East

ADAM@AdameMedia June 22, 2024:

How is it that nothing before October 7 justifies October 7…

yet everything after October 7 is justified because of October 7?

Profit over life and reason, always.

2024: More than 1,300 Hajj pilgrims have died this year amid scorching heat, Saudi Arabia says

And, then, there’s fur farming and so much more. With the massive selection of high quality easy-to-work with and wear alternatives to fur, why are humans still torturing fur bearers and running (farming) disease factories? Our heavily over populated world is too vulnerable to highly infectious and deadly pathogens to let human hideousness run rampant, yet we do, further proving how hideous our species is.

Freedom, always.

Freedom to cause horrific suffering to and wipe out other species, and, soon, our own.![]()

Michelle Wille@DuckSwabber June 21, 2024:

In 2023, 162 animals on 27 fox farms positive for HPAI. Many had ecrosuppurative bronchointerstitial pneumonia. Foxes and gulls in same area all had EA-2022-BB genotype and clustered together. Some mammalian adaptive mutations detected.

https://eurosurveillance.org/content/10.280

Tom Peacock@PeacockFlu:

Probably should have been aware of this but this line was still quite a shock to me:

“Dead and culled animals, which might have already been infected, were taken from the farms to be processed as feed for other fur animals”

Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infections on fur farms connected to mass mortalities of black-headed gulls, Finland, July to October 2023 by Lauri Kareinen, Niina Tammiranta, Ari Kauppinen, Bianca Zecchin, Ambra Pastori, Isabella Monne, Calogero Terregino, Edoardo Giussani, Riikka Kaarto, Veera Karkamo, Tanja Lähteinen, Hanna Lounela, Tuija Kantala, Ilona Laamanen, Tiina Nokireki, Laura London, Otto Helve, Sohvi Kääriäinen , Niina Ikonen, Jari Jalava, Laura Kalin-Mänttäri, Anna Katz, Carita Savolainen-Kopra, Erika Lindh, Tarja Sironen, Essi M Korhonen, Kirsi Aaltonen, Monica Galiano, Alice Fusaro, Tuija Gadd, June 20, 2024, Eurosurveillance Volume 29, Issue 25

Key public health message

What did you want to address in this study and why?

From July to October 2023, Finland experienced an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 on fur farms. We analysed the outbreak to identify the source(s) of the infection and possible transmission routes. We outlined the measures taken to mitigate the impact on human health and to prevent future outbreaks.

What have we learnt from this study?

We detected the HPAI H5N1 virus on 27 fur farms and showed that the virus belonged to the genotype circulating in wild birds in the same area. Thus, the outbreak was likely caused by direct contact with infected wild birds followed by virus transmission within and between farms, as suggested by genomic and epidemiological data. This finding highlighted the need to improve biosecurity measures on fur farms.

What are the implications of your findings for public health?

This outbreak demonstrated the vulnerability of fur farms to pathogens that can have severe human health implications. The virus spread efficiently in the farmed animals, creating many opportunities for spillover to humans. Strict biosecurity measures to cut transmission routes and robust surveillance in animals and exposed people for early detection of infections are required![]() but ignored, as usual, putting profit over reason and requirements

but ignored, as usual, putting profit over reason and requirements![]() for safe fur farming practices.

for safe fur farming practices.

… In October 2022, HPAI A(H5N1) 2.3.4.4b infection was detected in Spain in a single fur farm housing 50,000 animals. The outbreak was contained by culling all animals on the affected facility [6].

… Episodes of acute illness and mortality among farmed foxes, minks and raccoon dogs in Finland were reported to the FFA in July 2023 in the regions of South and Central Ostrobothnia. Following autopsy and real-time (RT)-PCR, the causative agent was identified as HPAI H5N1 with the first case confirmed on 13 July 2023 [8]. A case was defined as a farm where a positive H5N1 RT-PCR result from a swab, organ or faecal sample, even from a single animal, was obtained. Animals owned by different operators, but kept in the same establishment, were considered as a single epidemiological unit and managed as a single case.

…

Epidemiological investigation

Coordinated by the FFA, the fur farm operators were approached by the veterinary authorities in the Regional State Administrative Agencies (RSAA) for epidemiological investigation and interviewed using a questionnaire made for outbreak investigations on fur farms. The questionnaire covered mortality and clinical symptoms, patterns of disease, biosecurity measures and contacts with other animals or farms. The aim of the investigation was to identify the time and source of the infection and trace possible contact farms. Questions about personal protective equipment were also included and the names of the people in contact with sick animals were collected for public health authorities. In addition, information obtained about feed delivery routes, carcass collection and feed processing practices from feed operators were used in epidemiological investigation.

…

Epidemiological findings

Increased mortality was reported by 23 farmers, and on two fox farms this was the only symptom reported (Table 1). There was considerable variation in the way the mortalities were recorded by the farmers, but excess daily mortality was estimated by the farmers to range from none to nearly 10 times the normal seasonal average. The pattern of disease within the farms varied. Twelve farms reported only scattered cases, while six had observed sequential cases confined to a few shadow houses, whereas nine reported a progression of cases across multiple houses.

Fur animals were kept in shadow houses, in which two rows of metal wire cages, elevated 30–50 cm from the ground, are kept under a roof with an access corridor between the two rows, doorways at both ends and no solid walls. The affected farms were situated in an area with several lakes hosting populations of black-headed gulls. Wild bird mortalities in these areas were considered caused by HPAI. The gulls fly widely in the area and regularly feed on fur farms. While 16 of the 27 farms had structural or active deterrents against birds, these were typically only partially implemented, e.g. not used in all shadow houses and 11 reported having no measures in use against birds. Thus, the birds had easy access to animal feed inside the shadow houses and under the wire cages; as a consequence, direct contact with the fur animals represented the most likely transmission route to the farms.

When investigating connections between farms, some possibilities for between-farm transmission were identified. Dead and culled animals, which might have already been infected, were taken from the farms to be processed as feed for other fur animals.

There were no biosecurity measures at the carcass collection point at about 5–35 km distance from most farms in Kaustinen and used by most of the farmers. This could have acted as a point of virus spread between farms via vehicles, clothing or wild birds feeding on the carcasses. Even though the processing method of the carcasses is adequate to inactivate the virus, the processed feed may have been contaminated by bird faeces after processing and before distribution. The feed trucks, which deliver feed to many farms along the same route, fill the feed silos either from outside or inside the farm premises, however, no biosecurity measures were taken at the farm entrances. Despite this, the pattern of disease incidents and timing of infections excludes a major role for feed delivery or contamination of feed at the processing plant or interactions at the carcass collection site. Human-driven transmission event is likely to have occurred between farms B and X, which are located 75 km apart. The farms have genetically closely clustering viruses and the same owner, who handled animals on both farms, did not change clothing between farms.

…

To provide a legal framework for veterinary authorities to control HPAI on fur farms and protect humans from infection, on 18 July 2023, the MAF reclassified HPAI in fur animals from notifiable diseases to other diseases to be combated (MAF 909/2023 https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2023/20230909). This allowed the RSAA to impose restrictions on farms, such as forbidding animal movements to and from the affected farms, carry out epidemiological surveys and trace contact farms for sampling. In addition, the FFA had the legal authority to cull animals on infected farms and the owners were entitled to governmental compensations for the financial losses.

The MAF issued a more detailed national regulation (MAF 1068/2023 https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2023/20231068) on combating H5 avian influenza in fur animals on 8 December 2023. This regulation detailed a more specific framework for culling decisions and preconditions for restocking the affected farms. Weekly meetings were organised with the Finnish Fur Animal Association to ensure flow of communication and stakeholder support. The objective was to detect the infected farms as quickly as possible and prevent further transmission of the virus to fur farms, other animal farms or humans.

We initially conducted culling only in shadow houses with minks or other symptomatic fur animals. However, with more information available from virus sequencing and potential inter-species transmissions, the depopulation was extended to cover all fur animals on the infected farms. Culling was organised by the RSAA, and all the carcasses were taken to a rendering plant to be processed. Altogether ca 250,000 fur animals from the 27 infected farms were culled and processed.

Deficiencies in the biosecurity measures on fur farms allowing direct bird-mammal contact are a known risk factor for transmission of pathogens from wildlife to reared mammals [25]. Based on the findings from the genetic analyses, concurrent HPAI-related wild bird mass mortalities in areas surrounding the fur farms and the epidemiological investigations, the outbreak seems to be a direct consequence of the large-scale exposure of fur animals to infected wild birds.

During the outbreak, the A(H5N1) virus caused variable clinical symptoms in the animals, ranging from asymptomatic infections to fatal pneumonia and meningitis. The virus appeared neurotropic in fur animals, as the most common symptoms included neurological symptoms, such as tremors, disorientation and apathy, while respiratory symptoms were less frequent.

The severe inflammatory lesions in the lungs and the brain are indicative of the severe effect the virus can have on the host and underline the serious risks associated with any possible human cases.

Features of the outbreak have also diagnostic implications. During the outbreak, we considered using oropharyngeal swabs as a scalable, easy-to-implement sampling method to rapidly assess the situation on the farms in the affected area. However, the virus was not consistently detected from swab samples and in some animals only the brain or lung tissue tested positive. Because of this, we recommend that any investigation of suspected HPAI in a fur animal should always include testing of tissue samples.

…

Direct mammal-to-mammal or an indirect fomite driven transmission is implicated, and the genetic clustering of viruses on some of the analysed farms indicates that this may have happened. Within-farm virus evolution was particularly evident on farm A, from which sequences of viruses collected at two time points (3 July and 7 August) were available. All sequences from the farm cluster consistent with a single introduction followed by direct or indirect transmission. These viral sequences possess mutations not previously detected in birds and likely acquired after the introduction of the virus into the farms. Combined with the genetic data, our findings indicate that virus transmission between fur animals has most likely occurred, and this should be considered when planning strategies to prevent and combat HPAI in fur animals.

Phylogeographic analyses seem to indicate farm E as an important local hub in the outbreak, which contributed to the spread of the virus to other farms and back to wild birds. However, sampling bias cannot be excluded given (i) the higher number of available sequences of viruses collected from this farm (n = 12) compared with most of the other farms (1 < n < 14, mean 3.6 per farm) and (ii) the limited number of sequencing data from wild birds (n = 40). Although no direct connection from farm E to the other affected farms was identified by the epidemiological investigation, other routes of virus transmission, such as wild birds and human-related activities at the carcass collection point, cannot be ruled out. Farm E was among the largest facilities affected in this outbreak, with multiple incursions of highly related viruses from wild birds. Unfortunately, we have very few virus sequences from wild bird mass mortalities from the surrounding area, and therefore, the findings from farm E may reflect the virus diversity in the bird population rather than extensive intra-farm evolution and between-farm transmission.

Based on the available data, we cannot conclude how and to what extent the virus has been transmitted between farms.

Results from the epidemiological investigation showed that many farm practices may enable the spread of the virus, such as the open shadow houses, infrequent use of gloves or hand sanitisers and not changing protective clothing. Poor biosecurity measures at the carcass collection point, contaminated feed or vehicles may all have played a role, as well as the possibility of the birds or small rodents acting as vectors. Several of the farms are close to one another, and some share equipment, favouring possible transmission across farms when biosecurity and good hygiene practices are not followed. Further data are required to better understand how the outbreak spread and why so many farms in the area were affected.

In controlling the outbreak, a close co-operation between national and international veterinary and public health authorities was implemented. Containing the outbreak, limiting any exposure risks to humans and preventing future epidemics are the key priorities.

This large HPAI A(H5N1) outbreak demonstrates the vulnerability of densely farmed mammalian populations to pathogens present in the surrounding environment. To mitigate the continuing risk of novel outbreaks of avian influenza, efficient biosecurity measures should be![]() but given human nature, won’t be

but given human nature, won’t be![]() implemented to minimise direct and indirect contact between farmed mammals and environmental sources, especially wild birds. In Finland, a national regulation on biosecurity requirements on all fur farms to prevent birds having contact with the animals was issued by MAF on 15 January 2024 (MAF 14/2024). Although prevention of outbreaks is the main target, improving preparedness and response capacity of both fur farms and authorities is essential, as well as being alert for any increase in mortality on the farms. Virological surveillance designed for early detection of outbreaks is an essential part of disease control and we recommend active monitoring, especially when HPAI is found in bird populations in the vicinity of animal farms. The importance of implementing safer fur farming practices is highlighted by the observations of genetic changes during the outbreak associated with mammalian adaptation, which may increase the pandemic potential of the circulating avian influenza viruses.

implemented to minimise direct and indirect contact between farmed mammals and environmental sources, especially wild birds. In Finland, a national regulation on biosecurity requirements on all fur farms to prevent birds having contact with the animals was issued by MAF on 15 January 2024 (MAF 14/2024). Although prevention of outbreaks is the main target, improving preparedness and response capacity of both fur farms and authorities is essential, as well as being alert for any increase in mortality on the farms. Virological surveillance designed for early detection of outbreaks is an essential part of disease control and we recommend active monitoring, especially when HPAI is found in bird populations in the vicinity of animal farms. The importance of implementing safer fur farming practices is highlighted by the observations of genetic changes during the outbreak associated with mammalian adaptation, which may increase the pandemic potential of the circulating avian influenza viruses.

AJ Leonardi, MBBS, PhD@fitterhappierAJ:

The milk is being taste-tested at least

Oklahoma governor signs bill shielding poultry companies from lawsuits over chicken litter pollution, Lawmakers continue efforts to protect companies following federal lawsuits by Ben Felder, June 10, 2024, Investigate Midwest

….state lawmakers have taken multiple steps to deregulate the growing poultry industry and shield it from legal attacks.

Last year, Investigate Midwest reported how the state allows large poultry farms to avoid a more restrictive registration process and construct buildings that house thousands of chickens closer to homes and neighborhoods.

….even if the company violates a waste management plan, the bill appears to still prevent some lawsuits, as it states, “An administrative violation shall not be the basis for a criminal or civil action, nor shall any alleged violation be the basis for any private right or action.”

While state law once banned the discharge of poultry waste into state waters, the new law altered that language to say poultry operations shall take “measures designed to prevent” that from happening, which some believe weakens the law. …

Huge amounts of bird-flu virus found in raw milk of infected cows, New findings point to the milking process as a possible route of avian-influenza spread between cows — and from cow to human by Max Kozlov, June 5, 2024, Nature

Milk from cows infected with bird flu contains astronomical numbers of viral particles, which can survive for hours in splattered milk, new data show1,2. The research adds to growing evidence that the act of milking has probably been driving viral transmission among cows, other animals and potentially humans. …

US Dairy Cows Dying and Being Culled Due to Avian Flu by Ryan Hanrahan,

Jun 10, 2024, Farms.com

… “Reports of the deaths suggest the bird flu outbreak in cows could take a greater economic toll in the farm belt than initially thought. Farmers have long culled poultry infected by the virus, but cows cost much more to raise than chickens or turkeys,” Douglas and Polansek reported. “…Some of the animals died of secondary infections contracted after bird flu weakened their immune systems, said state veterinarians, agriculture officials, and academics assisting in state responses to bird flu. Other cows were killed by farmers because they failed to recover from the virus.”

Laura Miers@LauraMiers:

*For profits and convenience. We are killing our futures so a few men can get richer.