Open records case produced untracked drilling documents by Laura Legere, May 19, 2013, Times-Tribune

Scattered records kept by the state Department of Environmental Protection offer one answer to a key question in a new age of fossil fuel extraction in Pennsylvania: How many water supplies have been damaged by drilling? The Sunday Times requested the letters and enforcement orders that might best account for the number of drilling-disrupted water supplies in 2011. The letters are known as “Section 208 determination letters” or “208 letters” after the former portion of the now-revised state oil and gas law that describes DEP’s obligation to investigate and respond to complaints of water impacts by drilling. Regulators send the letters to public and private water supply owners to announce the results of their investigations. Taken together, the founded and unfounded complaints mark sites where people lost confidence in their drinking water and, in some cases, where the state also trained the blame on nearby oil and gas operations. Prior to the newspaper’s request, the state had not kept track of the records.

At first, DEP responded by releasing those letters and orders to the newspaper that it could locate based on its databases and “institutional memory” and rejected the rest of the request as insufficiently specific to allow it to find the rest of the documents. During a series of appeals, the department defended its filing system as suiting DEP’s regulatory purposes even as it described the files’ unwieldy organization.“There are tens of thousands of oil and gas files in each region,” the agency wrote, “and without specific identifying information such as a specific county with permit numbers or well numbers, site names or facility names, it is impossible to determine in which files 208 letters would be found. The department does not maintain an index of 208 letters and there is no accurate way to isolate all of the records requested. The department does not electronically track letters via a database.” The DEP acknowledged at one point that it “does not know how many letters have actually been issued.”In affidavits, the head or file review coordinator of each regional DEP oil and gas office described the limits of the filing system and their efforts to navigate it to find responsive records. Both the Northcentral and Northwest Regional offices located orders to drillers to replace water supplies then tried to trace them to individual letters sent to water well owners. The Southwest Regional Office maintains a complaint database by county and date, but it “has no database indexing in any fashion which complaint files pertain to allegations of contamination or diminution of water supplies and therefore might contain Section 208 determination letters,” the agency wrote.

It would be impossible to find all of the requested records without doing a file-by-file search of each of the thousands of files, the department argued.

In July 2012, a three-judge panel of the Commonwealth Court ruled that DEP had to turn over all of the records because “there is simply nothing in the [Right to Know Law] that authorizes an agency to refuse to search for and produce documents based on the contention it would be too burdensome to do so.” “It cannot be inferred” from the Right to Know Law, the court said, “that the General Assembly intended to permit an agency to avoid disclosing existing public records by claiming, in the absence of a detailed search, that it does not know where the documents are.”

The state released the records last fall after the full Commonwealth Court denied its request to reconsider the ruling. DEP spokesman Kevin Sunday said the department was able to locate all of the records when “each district office reviewed the appropriate files in their possession.” [Emphasis added]

…

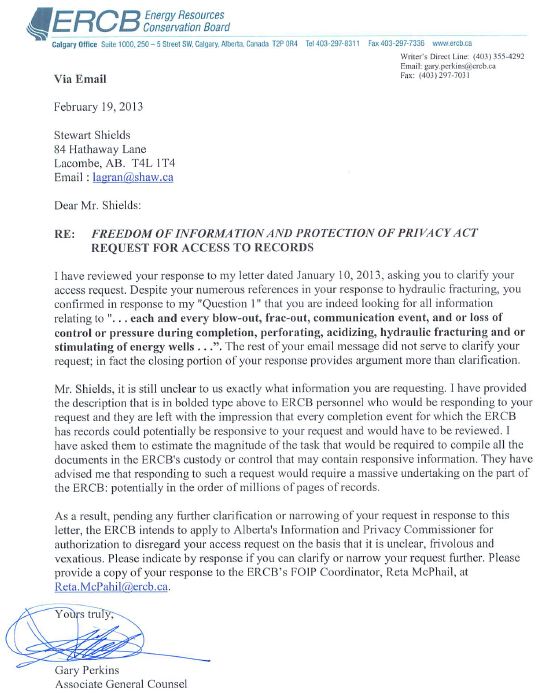

Could it be any clearer? An Albertan’s request for information by Admin, May 20, 2013

Albertan requests information from the regulator for “each and every blow-out, frac-out, communication event, and or loss of control or pressure during completion, perforating, acidizing, hydraulic fracturing and or stimulating of energy wells” in Alberta.

ERCB’s General Council responds and threatens to apply to Alberta’s Information and Privacy Commissioner for authorization to disregard the access request “on the basis that it is unclear, frivolous and vexatious”

“Responding to such a request would require a massive undertaking on the part of the ERCB: potentially in the order of millions of pages of records.”

…

Sunday Times review of DEP drilling records reveals water damage, murky testing methods by Laura Legere, May 19, 2013, Times Tribune Sunday Times

First of two parts

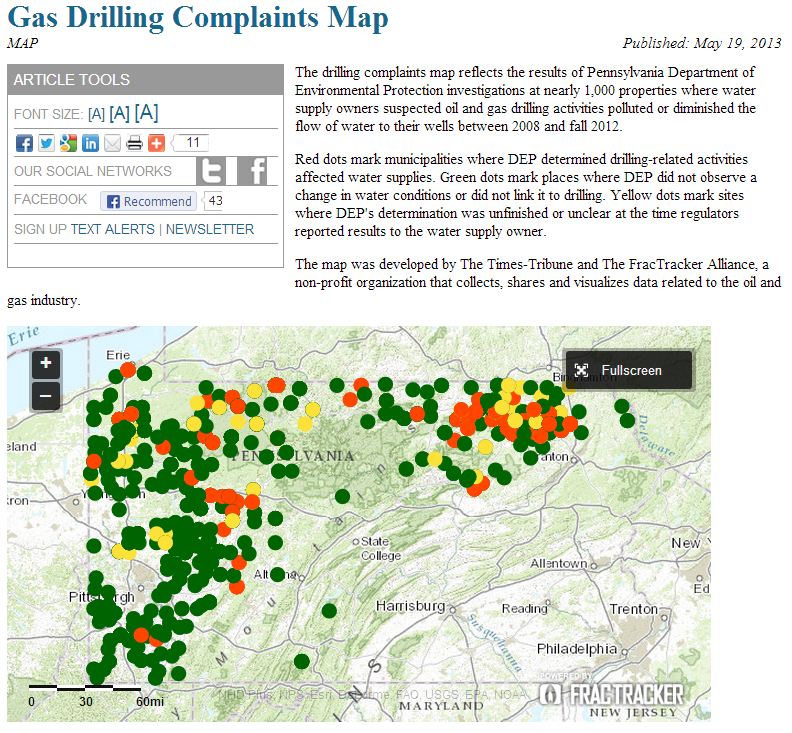

State environmental regulators determined that oil and gas development damaged the water supplies for at least 161 Pennsylvania homes, farms, churches and businesses between 2008 and the fall of 2012, according to a cache of nearly 1,000 letters and enforcement orders written by Department of Environmental Protection officials and obtained by The Sunday Times. The determination letters are sent to water supply owners who ask state inspectors to investigate whether oil and gas drilling activities have polluted or diminished the flow of water to their wells.

View interactive map: Gas Drilling Complaints Map

Inspectors declared the vast majority of complaints – 77 percent of 969 records – unfounded, lacking enough evidence to tie them definitively to drilling or caused by a different source than oil and gas exploration, like legacy pollution, natural conditions or mining.

One in six investigations across the roughly five-year period – 17 percent of the records – found that oil and gas activity disrupted water supplies either temporarily or seriously enough to require companies to replace the spoiled source. The letters confirming contamination or water loss from drilling and the orders that require companies to fix the damage provide what is likely the best official count of the industry’s impact on individual water supplies in Pennsylvania because the state does not track the disruptions.

The Sunday Times requested the records in late 2011, and received access to them late last year after a state appeals court ruled that the DEP had to release the documents regardless of whether it was hard for the agency to find them in its files.

While the records compiled by the newspaper offer a more complete tally of the number of affected properties than was previously available, the count is not exhaustive:

– DEP tracks oil and gas-related disruptions to water supplies based on broad incidents, each of which might affect one or many water supplies, making comparisons between the totals difficult. A case of gas migrating into Dimock Twp. drinking water, for example, is considered one incident by DEP even though the state determined it affected 18 water wells used by 19 families. …

– DEP repeatedly argued in court filings during the open records case that it does not count how many determination letters it issues, track where they are kept in its files or maintain its records in a way that would allow a comprehensive search for the letters, so there is no way to assess the completeness of the released documents.

– Before a 2011 regulatory update, solutions worked out privately between homeowners and drillers were not required to be reported to the department. The Sunday Times requested the notices of potential water contamination that now have to be passed on to DEP by drilling companies that receive them from residents, but the request was denied by DEP and the state’s Office of Open Records because the documents are considered part of protected investigations.

– The conclusions described in the determination letters are seldom absolute because substances read as signals of drilling-related contamination are also routine signs of other man-made or natural influences.

…

Transparency questioned

The department’s water testing and reporting protocols have come under scrutiny in recent months as environmental activists and homeowners whose drilling-related complaints were dismissed have come to doubt the determinations’ accuracy and value. DEP recently changed its policy for issuing water contamination notices to require administrators in Harrisburg to approve them before they are sent out from the regional field offices that conduct the investigations. The state’s laboratory technical director, deposed when a resident appealed the DEP’s conclusion that drilling activities had not polluted his water supply, acknowledged that DEP reviews and reports back to homeowners only those contaminants it considers indicative of drilling-related contamination, not all of the contaminants that might surface in its water tests – a common practice for tailoring laboratory analysis but one that spurred critics to question the thoroughness and transparency of DEP’s investigations. In January, state Auditor General Eugene A. DePasquale announced his office is conducting a performance audit of the DEP’s water testing program to “determine the adequacy and effectiveness of DEP’s monitoring of water quality as potentially impacted by shale gas development activities” between 2009 and 2012.

…

But the determination letters released by the state reveal a widespread suspicion among water supply owners – farmers and summer residents, school board members and mini-mart operators, churches and a Wyoming County municipal water authority – that when their water seems soured, gas drilling operations might be to blame. According to the state’s records, they are sometimes right and for a myriad of reasons. More than half of the records of contaminated water supplies confirmed by the state involved gas, loosened by drilling, seeping into drinking water aquifers. Faulty natural gas wells channeled methane into the water supplies for 90 properties, the letters show. Three of those cases were tied to old wells, one of which caused an explosion at a home after gas entered through a floor drain and accumulated in a basement. Drilling-related road construction contaminated water at two homes, while construction for a large water-storage pond called an impoundment contaminated another. Pipeline construction twice polluted water supplies with sediment. Stray cement or rock waste displaced by drilling, called cuttings, contaminated seven water supplies.

The state has never implicated the underground gas extraction process known as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, in a contamination incident, but inspectors noted that brine contamination suggesting “an infiltration of frac water into the shallow ground water,” damaged six fresh-water springs used for drinking water in northwestern Pennsylvania.

The natural gas industry has worked on several fronts to investigate and respond to contamination complaints, including providing drinking water to homeowners while their concerns are investigated, she said. The organization and university partners are also compiling a database of pre-drilling groundwater quality to help researchers assess background water quality and insulate operators from misplaced blame.

…

Regulations could help address pre-existing water quality problems and make sure water wells are stable enough to handle any nearby industrial activity, including oil and gas operations, she said. “When you’ve got vibration and activity proximate to an unlined water well you’re going to get infiltration of dirt and other materials. That turbidity, usually temporary, is going to affect that water.”

…

DEP blamed a Marcellus Shale driller in Susquehanna County for water contamination in 2010 after the salt, barium, strontium and gas concentrations in the Rush Twp. home’s water supply spiked after the company drilled and fracked a well 600 feet away. The post-drilling barium levels reached 47 milligrams per liter – more than 23 times the safe level of the toxic metal in drinking water – while the TDS, chloride and sodium levels peaked at more than 10,800, 5,800 and 3,800 milligrams per liter, respectively – more than 20 times the guidance levels set for aesthetic reasons like taste and appearance. The determination letter and the subsequent order requiring the driller, Stone Energy, to replace the water well do not describe the mechanism for the pollution. Instead, Mr. Sunday said, the company was presumed responsible for the contamination based on the timing of the impact and the distance from the gas well and the company did not rebut the state’s finding. Stone Energy believed its drilling activity was not to blame for the pollution, but agreed to drill the homeowner a new water well and repay him for out-of-pocket living expenses without admitting to causing the problem, according to the enforcement order.

…

Anthony Ingraffea, Ph.D., an engineering professor at Cornell University and a vocal critic of the oil and gas industry he once worked for, said that when DEP says it cannot find a connection between water well contamination and nearby gas activity it does not mean there is no link. “If DEP sent me a letter that said, ‘We can find no connection,’ my natural question as a scientist would be, ‘How did you look?'” he said. He was concerned by DEP’s practice of counting cases without counting individually impacted water supplies, which he said “makes their statistics look better.” [Emphasis added]

Source: Times Tribune, Click on map to access fullscreen

Scientists find new tools for tracing fracking impacts by Laura Legere, May 20, 2013, Times-Tribune

Second of two parts

“It’s hard to tease out the contamination signal from the natural variability,” Syracuse University hydrologist Laura Lautz said. “It’s even harder to do that when you don’t have the baseline water quality data.” … The team has found that studying the quantity and relative concentrations of chloride, bromide and iodide together can be a “very, very powerful” indicator of Marcellus formation water compared to other salt waters, she said. The problem is that too few people test for them. Neither bromide nor iodide is included in the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s recommended list of basic pre-drill water test parameters and they are not among the constituents analyzed during DEP’s standard test for post-drilling water contamination investigations. They are also rarely included in historical data sets for regional groundwater. …

Unlike regulators, who generally gauge impacts based on whether substances in drinking water rise above advisory limits set for safety or taste, researchers are looking for subtler indicators. It is “absolutely” possible to have detectable contamination without any chemical parameters in the water rising above safe drinking water limits, Dr. Vengosh said. “Good monitoring systems actually identify it at that point,” then track any changes, he said. “The way to do monitoring is to be able to identify it in the early stages before it becomes dangerous.” [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to: