PART 1; Leaking wells a burning issue, Critics see energy industry’s plumbing problems as a threat to climate, water, safety by Margaret Munro, Postmedia News, December 8, 2014, ocanada.com

Methane gas venting from a pipe on one well in Ste-Francoise, Que. Photo courtesy CMAVI

Serge Fortier has been trying for years to raise awareness about leaking wells along the St. Lawrence River. Nothing has been quite as effective as setting them on fire. “The reaction came very rapidly,” says Fortier, an environmental activist whose fiery demonstration near Ste-Francoise has prompted the Quebec government to acknowledge it has a problem – one that regulatory officials are often not keen to discuss.

In Alberta, where old wells have been uncovered in schoolyards, backyards and at shopping malls, officials are saying little about a well that has now turned up at Calgary’s airport, which is in the midst of a $2-billion expansion.

“There is an investigation right now with respect to an abandoned well at the airport,” Brenda Cherry, vicepresident of closure and liability at the Alberta Energy Regulator, told Postmedia News. She would not comment on whether the airport well is leaking or if it’s under the new 4.2-kilometre runway, saying details are “confidential” until the investigation is complete. And in British Columbia, where it’s estimated as many as 10 per cent of oil and gas wells leak, one leak reportedly cost $8 million to repair.

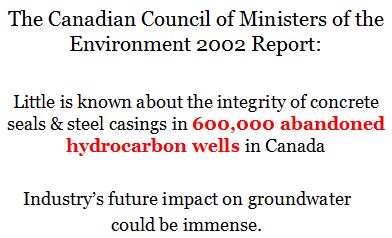

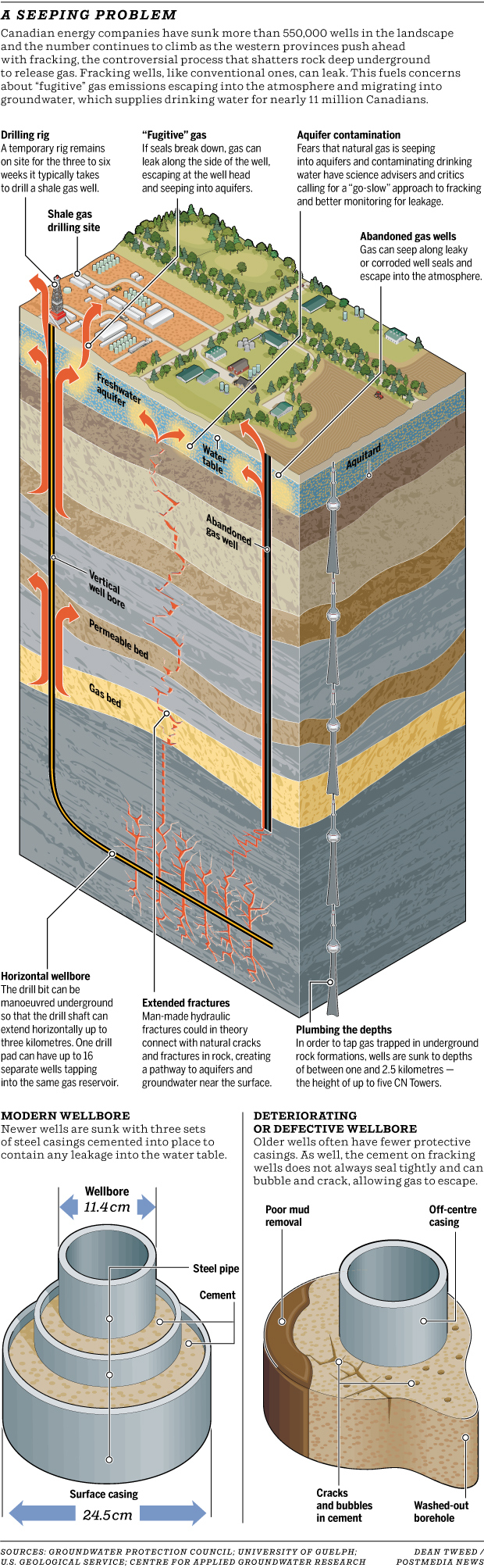

More than 550,000 holes have been drilled in Canada since North America’s first well gushed “black gold” in southern Ontario in 1858. And industry is boring another 10,000 wells a year as controversial fracking operations in Western Canada extend their reach.

As the wells proliferate, so do concerns about the way many of the kilometresdeep holes in the ground are leaking because of cracked, poorly formed and decaying plugs and seals. [What about the terrifying consequences of Encana perforating and fracing directly into community drinking water supplies?]

Industry says the plumbing problems can be managed, but questions mount over the way the wells are compromising not only the landscape but the water and resources below.

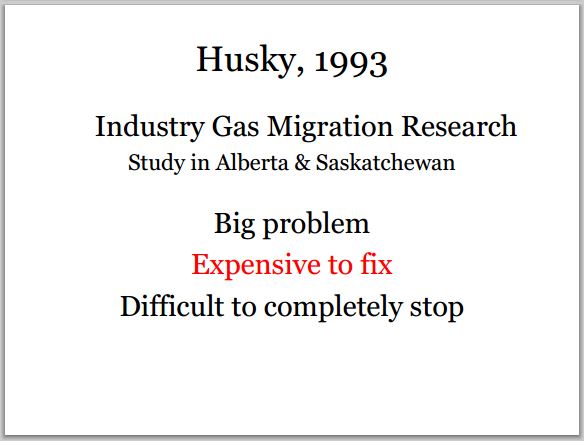

Research suggests that tens of thousands of wells are leaking and some experts argue concerns over fracking are misplaced, saying “wellbore leakage” is the bigger threat.

The leakage affects fracking, as well as conventional oil and gas wells, and is “the more significant issue affecting the social licence of the oil and gas industry,” says a recent University of Waterloo report that describes the leaks as “a threat to the environment and public safety.”

The “fugitive” gases often escape from geological formations that oil and gas wells slice through on their way down to the energy deposits being targeted. The gas is buoyant and seeps up through cracks and poorly cemented seals on the wells.

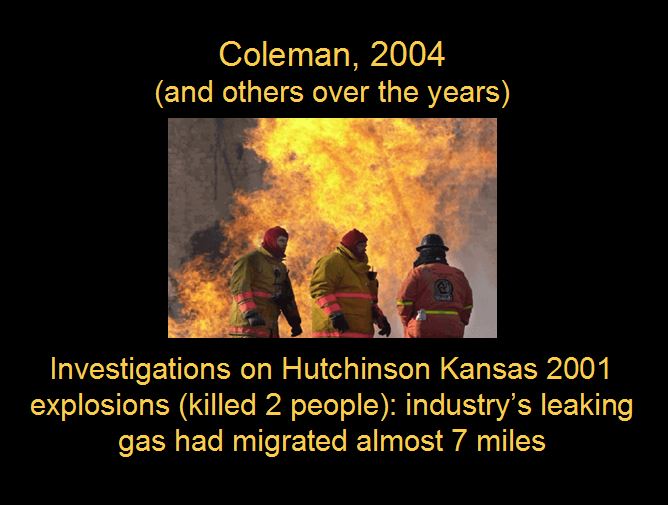

Much of the leaking gas is methane, the main component of natural gas and a potent greenhouse gas. The gas escapes into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change, and can cause explosions when it accumulates in poorly ventilated areas. The gas also can seep through the ground, potentially contaminating groundwater, which 30 per cent of Canadians depend on for their drinking supply.

Industry and government regulators say the leaks can be plugged and “safely” managed. Critics like Fortier are anything but convinced.

[Industry and regulators have known for decades that the leaks cannot be completely fixed]

“The solution is to stop drilling wells,” says Fortier, of the Collectif Moratoire Alternatives Vigilance Intervention.

He does not believe that wells, which cut down through ancient geological formations, can ever be adequately resealed and points to the sorry state of the 700 wells in Quebec as evidence. Methane is leaking from both shale gas wells drilled since 2000 and wells drilled decades ago.

At the media event in August in Ste-Francoise, Fortier set fire to the gas venting from a pipe on one well. He also lit gas seeping out of the ground near the wells.

The Quebec government announced in mid-October an “action plan” to step up inspections and work with Fortier’s group to locate and assess the wells that are concentrated along the St. Lawrence River.

Many are in forested areas, but Fortier says some were drilled in Lake Pierre, where the St. Lawrence River widens and boaters report seeing gas bubbling to the surface.

The job of monitoring and repairing Canada’s wells could be endless as leaks can develop when wells are operating and long after the oil and gas operators pull out.

Researchers say seals, plugs and repair jobs can fail years after wells are abandoned. The “bridge plugs” commonly used to abandon Canadian wells are prone to “mechanical failure,” according to one report done for Alberta’s energy regulator. It predicted 10 per cent of abandonments that use “bridge plugs” may fail in the decades and centuries ahead.

Geotechnical and groundwater specialists, who assessed the environmental impacts of shale gas fracking for the federal government, also pointed to leakage as a “long-recognized yet unresolved problem.”

They say oil and gas wells may need to be monitored “in perpetuity because, even after leaky older wells are repaired, deterioration of the cement repair itself may occur.”

The panel’s report, released this spring, says there is an “ethical imperative to avoid passing on the responsibility for well maintenance and impact monitoring to future generations.” It advocated a “go-slow” approach to shale gas fracking, in part because of the leakage problem dogging the industry.

Quebec and the Maritime provinces have put the brakes on fracking but “slow” is not a word often associated with the operations underway in the forests of northern B.C. and Alberta. More than 2,000 fracking wells have been drilled, and there are plans for thousands more.

Proponents, such as federal Finance Minister Joe Oliver, play down the risks. “Fracking has been going on in British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan for over 50 years,” Oliver said in September as he criticized Nova Scotians for banning fracking. There has not been “a single case” of drinkable water contamination, Oliver said. “So the record is long, it’s clear, it’s unambiguous and it’s unblemished.”

Researchers say not so fast. One reason few problems have surfaced, they say, is because little effort is made to find them. “Evidence is critical,” says Richard Jackson, an engineer and groundwater expert at Ontario-based Geofirma Engineering Ltd. and co-author of the University of Waterloo report.

Provincial regulators do require companies to test for and repair “serious” leaks in the casings of operating wells, known as “surface casing vent flows.” This gas vents into the atmosphere. But this is “most likely only part of the gas that is migrating” because “subsurface emissions remain unquantified,” say Jackson and his colleague Maurice Dusseault at Waterloo.

Geologist Karlis Muehlenbachs, at the University of Alberta, has been sampling the gas on the move.

He fingerprints gas for operators trying to pinpoint and repair leaks and says “brand new multi-frack shale gas wells are having the same kind of problems as the old conventional wells.”

“None of which should come as much of a surprise,” says Muehlenbachs, noting how fracking wells are punctured with small explosives so water can be injected under intense pressure deep underground to fracture or shatter rock. “It’s like standing by your plumbing at home and hitting it with a hammer.”

Muehlenbachs, like researchers in the U.S., has found leaks tend to originate in gas beds that wells cut through on the way down to deeper oil and gas zones. About 75 per cent of the leaks he’s tested on B.C. fracking wells were partway down the wellbores.

Muehlenbachs’s group has also shown how gas liberated by oil and gas wells in Alberta and Saskatchewan can seep through the ground – findings that bolster assertions by some landowners that oil and gas operations are contaminating their well water.

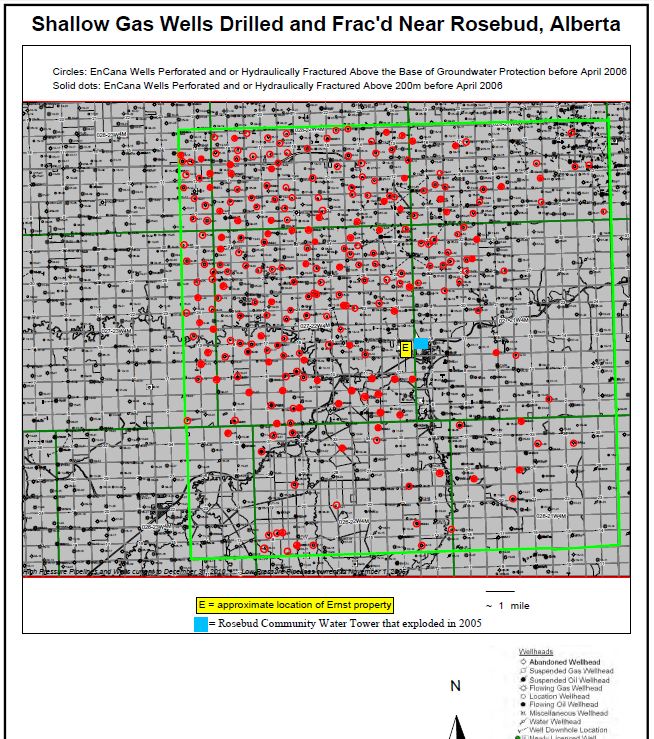

In one long-running battle, Jessica Ernst has filed a $33-million lawsuit against the Alberta government and energy company Encana, alleging fracking on her land northeast of Calgary contaminated her well water. In the latest development, a judge ruled in November that Ernst can sue the Alberta government for not properly investigating her concerns that Encana contaminated her well water, which contains so much methane she can light it on fire.

Industry says there has never been a proven case of fracking contaminating drinking water, but it does acknowledge “surface casing vent flow” is a problem that enables gas to seep up cracked, corroded, and poorly sealed and cemented wells.

A new Canadian standard and an industry recommended practice are being developed to address the “challenges” of sealing new wells and the “remedial” repair of old wells, says Brad Herald, vice-president of Western Canada operations at the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers.

While methane is flammable and a potent greenhouse gas, he notes that the naturally occurring gas is not toxic to humans. “It’s not cyanide,” says Herald.

[Reality check: There are no studies proving that breathing methane venting from household water taps every day is not harmful to health. Methane is explosive and an asphyxiant. Toxicity levels matter not after you are killed in an explosion caused by industry’s leaking methane:

May 2006, Alberta: Bruce Jack in hospital after his water well contaminated with industry’s methane exploded during testing by industry. Two workers were also seriously injured and hospitalized.

May 2006, Alberta: Bruce Jack in hospital after his water well contaminated with industry’s methane exploded during testing by industry. Two workers were also seriously injured and hospitalized.

2014, Orwell, Ohio: Woman dead, man seriously injured in house explosion caused by migrating methane

2014, Orwell, Ohio: Woman dead, man seriously injured in house explosion caused by migrating methane

Some jurisdictions are stepping up inspection of abandoned wells. The Quebec government announced plans in October to assess the 700 old wells in that province within the next three years. And after old leaking wells started turning up in new subdivisions and developments in Alberta, the Alberta Energy Regulator issued a directive two years ago that requires energy companies to inspect the hundreds of old wells near existing or planned developments, and reassess them at least once every 10 years.

But with more than [500,000] abandoned wells in Canada there is a long way to go, and Dusseault and Jackson predict the problem “will likely only become worse with time.”

The evidence suggests “leakage as the result of abandonment failure will significantly increase” in coming decades, it says, and “with it gas leakage problems.” [Industry and regulators have known about this serious, expensive problem for decades. As the problems worsen, regulators escalate deregulation.]

By the numbers [Is reporting of the numbers voluntary?]

– 10 per cent of the 24,000 active and suspended wells in British Columbia leak. Some “super-emitters” have pumped out large amounts of methane, with one leaky well in northeastern B.C. costing $8 million to repair.

– Many of Saskatchewan’s 90,000 wells are concentrated in the Lloydminster area, where 20 per cent of wells leak gas into the air or ground. [And into groundwater, as proven by CAPP and the regulators in the 90’s: Part One, Part Two]

– Alberta has close to 450,000 wells and 27,000 well leaks have been reported to government regulators since 1971.

– 20 per cent of the 50,000 oil and gas wells in Ontario have “minor vent flows.”

– 18 of the 28 shale-gas wells in Quebec have “minor leaks.” Quebec also has 900 older wells, many of which are leaking gas.

– Two of 29 producing wells in a gas field in New Brunswick have measurable leaks.

Source: University of Waterloo, provincial governments, CMAVI [Emphasis added. Slides added above from Ernst presentations]

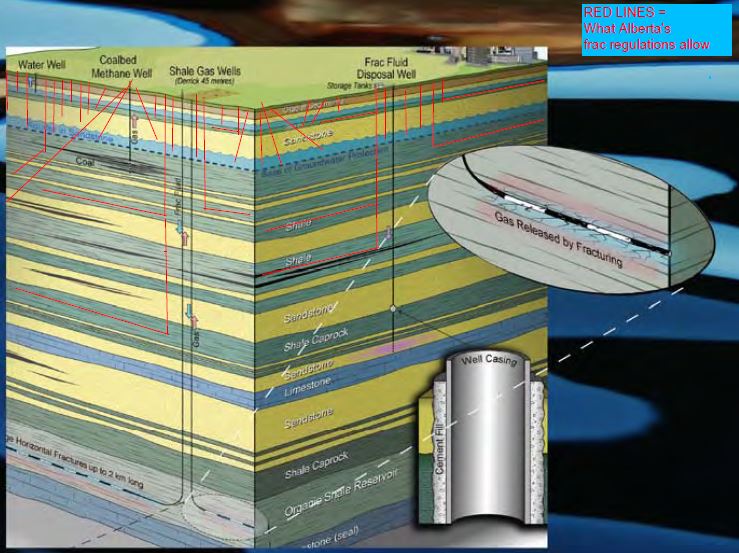

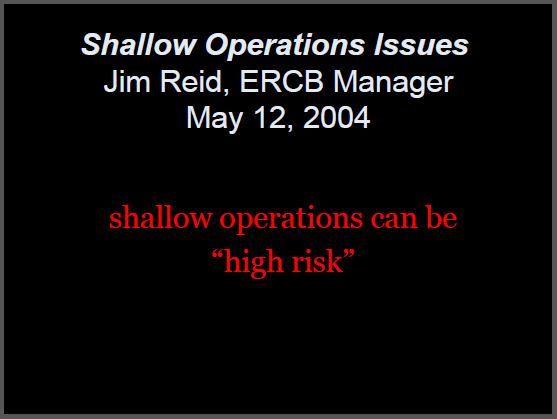

[Reality check to the diagram above:

ERCB (now AER) propaganda presented to the public and concerned landowners, September 2011. The dotted blue line = the Base of Groundwater Protection. The red lines below show what the AER allows industry to do:

The red lines indicate where oil and gas companies have and are fracing in Alberta. The dotted blue line = the Base of Groundwater Protection

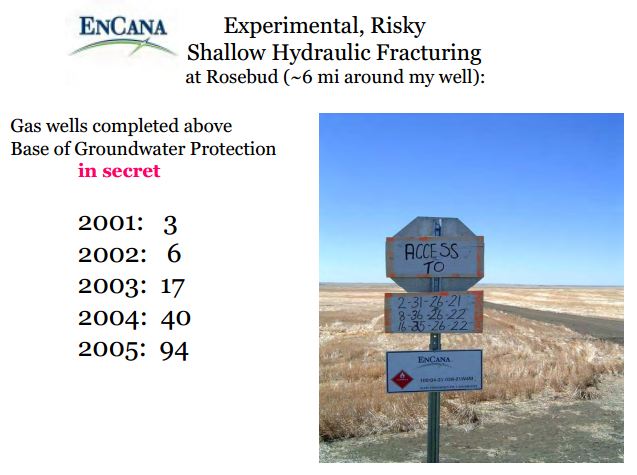

Encana gas wells frac’d above the Base of Groundwater Protection around Rosebud, before April 2006, compiled with Encana data on file with the Alberta Energy Regulator

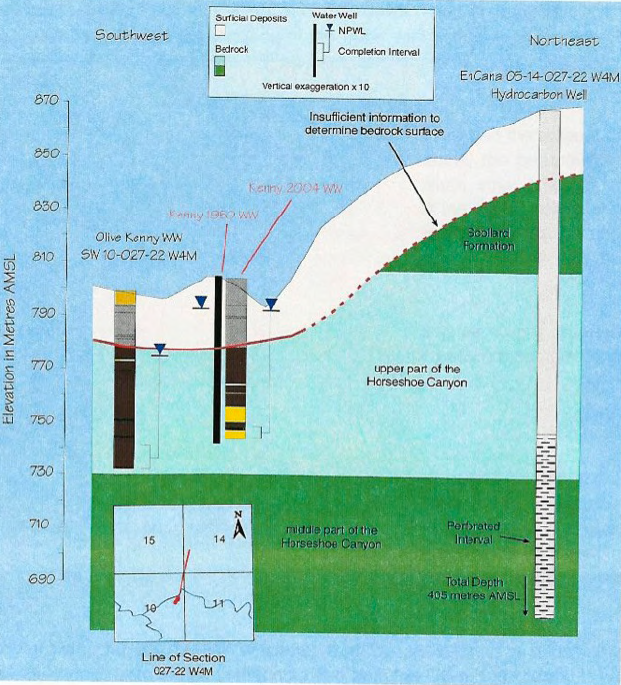

Encana’s 2004 repeat fracs into Rosebud’s drinking water aquifers. Diagram in the 2005 report by Hydrogeological Consultants Ltd for Encana.

Encana’s 2004 repeat fracs into Rosebud’s drinking water aquifers. Diagram in the 2005 report by Hydrogeological Consultants Ltd for Encana.

PART 2: Trouble Beneath Our Feet – Trying to plug the leak in Calmar, Alberta: Five years, five homes demolished and gas keeps bubbling from the deep (with video) by Margaret Munro, Postmedia News, December 8, 2014, ocanada.com

Imperial Oil workers came knocking in Calmar, a small town southwest of Edmonton, looking for old oil and gas wells in 2008. They found one leaking just a metre from the Beaudry home on Evergreen Crescent and took drastic steps to try to stop the gas rising from the deep. Imperial bought up the Beaudry home and four neighbouring houses. Then it demolished them to make way for a drill rig. Workers bored down a kilometre last year, scoured out the old well, and then poured in cement to try plugging the leak.

Millions of dollars later, gas is still bubbling up and the leak is worse now than when they started. “Clearly we are not satisfied with this re-abandonment attempt,” says Chris Sieben, a senior engineer at Imperial. “It did not go as planned.”

…

And “it’s been an absolute nightmare” for Ralph Olson, who has watched the Calmar saga unfold outside his dining room window. Six months after Olson and his wife moved into the new subdivision, the old leaking well was uncovered.

The Olson home was deemed too far from the well to qualify for a buyout from Imperial. They’ve seen neighbours and close friends move away and watched Imperial demolish the five homes to make way for the drill rig.

The community had been oblivious to the well until workers digging in a schoolyard hit old pipes in late 2007. The discovery led to Imperial, which was called in to help check for and track down other wells in Calmar.

In addition to the old gas well in a schoolyard, it found one under a community park and the one on Evergreen Crescent. Imperial inherited the wells through a merger with Texaco in 1989.

Andy Biblow, project manager for Imperial’s Calmar project, says the leaks were small and posed no threat to people or the environment. But the wells had “wellbore integrity issues” and needed to be brought in line with Alberta’s rules that say abandoned wells must be “incapable of flow.”

After plugging the wells at the school and park, Imperial moved on to the well on Evergreen Crescent, which proved a much bigger challenge.

It took years to settle with some of the homeowners, who argued that their homes were worth up to $75,000 more than Imperial was offering. By the summer of 2013 the demolitions were complete and the drill rig rumbled down the street.

“It was a brutal summer,” Olson says of the noise and dust kicked up by the work crews. At one point he looked out to see portable toilets “right underneath my dining room window.” The company moved them after he complained.

The well was leaking methane gas, which seeps out of many oil and gas wells with faulty seals, plugs and well casings. Old wells are especially problematic as they were abandoned to laxer standards — crews were known to stuff everything from old boots to overalls down the wells and then dump in a bucket or two of cement.

All of which can lead to “abandonment failure” and leaks of methane and other gases escaping from layers of rock that the wells slice through.

Sieben, Imperial’s conventional reservoir and subsurface engineering supervisor, says the first step in a “reabandonment” is to install a new wellhead, then “hot tap” the well so a crew can work on it. The old well plugs are drilled out and equipment is lowered down to zero in on the source of gas.

Sieben says a “perf and squeeze” can usually solve the problem. This entails setting off small charges of solid rocket propellant to strategically perforate holes in the casing lining the well. Then cement is squeezed through the holes to fill gaps and stop the leak. Then comes a “bubble test” to see if it worked. If it did, the well is cut and capped at least a metre underground and the site is restored.

“Every well is unique,” says Sieben, noting the success rate is not 100 per cent.

In Calmar, cement casing did not extend to the bottom of the wells so the repair entailed plugging up the wells with cement to a depth of 1,000 metres.

On Evergreen Crescent the crew “had issues” when it poured the cement into the well, says Sieben: “One of the (geological) zones that was open to the wellbore basically drank some of the cement.”

The engineers say removing the existing barriers and restrictions in the well may have also opened up other fissures. “Until we’re able to actually crawl down with our eyes and see what happens subsurface — which we can’t do — it is hard to tell what the real cause is,” says Biblow.

But he says the well is now emitting more gas than when it was found in 2008.

“It is greater today than it was before,” says Biblow. About 2.3 cubic metres of methane a day is now escaping from the well — about as much as comes out the hind end of three cows, he says. It is “not hissing” gas but the bubbles are “continuous.”

Second Calmar well leak site

Imperial is venting the gas to the atmosphere and monitoring the flow before a decision is made on what to do next. “We would not be able to cut and cap this well in its current state,” says Sieben. He and Biblow say one option may be to bring a drill rig back in and try again. A decision, expected by early next year, will be made in consultation with the Alberta Energy Regulator and the community. Imperial does not disclose how much it spends on “reabandonments” but leak repairs are said to typically run about $150,000 while complicated jobs have been known to cost as much as $8 million.

After the fiasco in Calmar, Alberta oil companies stepped up testing of wells in and near urban areas. Biblow says three of the 82 wells Imperial has tested are leaking small amounts of gas in parks in Redwater, a small community northeast of Edmonton. Playground swings and slides were removed this fall, making way for a drill rig. By spring Imperial hopes to have the Redwater repairs completed, the wells capped and new playgrounds installed.

In Calmar, the plan is also to turn the gravel work site on Evergreen Crescent into a park. “If it ever happens,” says Michelle, who moved onto the crescent with her husband and three children, taking advantage of house prices that are said to have dropped as much as $40,000 after the leaky well was discovered.

Michelle, who did not want her surname published, said they were aware of the well when they purchased and are not worried about the leak. The real estate deal included a paid vacation when the noisy drill rig bore down on the old well last year.

Many in the community would rather not discuss the leaking well, but Olson would like to see something positive of the fiasco that tore the neighbourhood apart and has left him feeling “stuck, cornered and abused.”

He says there should be much tougher legislation to ensure more homes and buildings do not end up next to leaking wells. He would also like to see a law that requires industry to check all abandoned wells, especially those within a kilometre of where people live and work, for leaks once or twice a year. “Not just when problems arise,” he says. “Otherwise if they don’t get caught, they won’t do anything,” says Olson.

Concerns over Canada’s abandoned and inactive wells

Alberta has about 155,000 abandoned wells and another 80,000 “inactive” wells that have been temporarily suspended, in some cases for years.

About 40,000 of the inactive wells do not appear to be compliant [Appear? Shouldn’t a regulator know?] with suspension requirements that stipulate everything from how often they need to be checked to how the records are kept, says Brenda Cherry, vice-president of closure and liability at the Alberta Energy Regulator that oversees the 450,000 oil and gas wells in the province.

In response to a directive from the agency in 2012, energy companies have checked 387 old wells in and around urban areas over the last two years, says Cherry, who oversees “end of life” activities that entail plugging, cutting and capping wells.

She would not say how many of the wells are leaking, adding it is up to industry to release the information. But she says abandoned wells have been uncovered in some unexpected places, including a shopping mall in Airdrie, north of Calgary, and at Calgary’s expanding international airport.

“The piece that we’re particularly focused on is to ensure the wells are in a safe and secure condition whether they are suspended or abandoned,“ Cherry said in a recent interview.

Provincial auditors in British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan have raised concern about the way energy companies have been drilling new wells much faster than they are getting on with the multi-billion-dollar job of abandoning inactive wells.

The companies, which have “perpetual” responsibilities for their wells in the western provinces, do not see inactive wells as liabilities but as valuable assets, says Brad Herald, vice-president of Western Canada operations at the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. He says the intent is to bring them back into production when, and if, energy demand and prices improve.

Herald says the industry is a leader in “looking after closure liability” and will cover the costs of abandoning all wells, including the ones orphaned by defunct companies.

He has no comment on the situation in Quebec, where environmental groups say hundreds of old wells are leaking and taxpayers are liable for the repairs. A Quebec government spokesman had no comment on whether the government would ask industry to pay for the well repairs. “Unfortunately, I have no information about that,” says Nicolas Begin, a media officer with Quebec’s ministry of natural resources. [Emphasis added]

PART 3: Trouble Beneath Our Feet, Energy wells can ‘communicate’ and ‘sterilize’ the landscape by Margaret Munro, ocanada.com

The sun was beginning to set on the farm near Innisfail, a two-hour drive south of Edmonton, when a wellhead suddenly started spewing oil and fracking fluids 20 metres into the air, coating the snowy field and trees in oily mist.

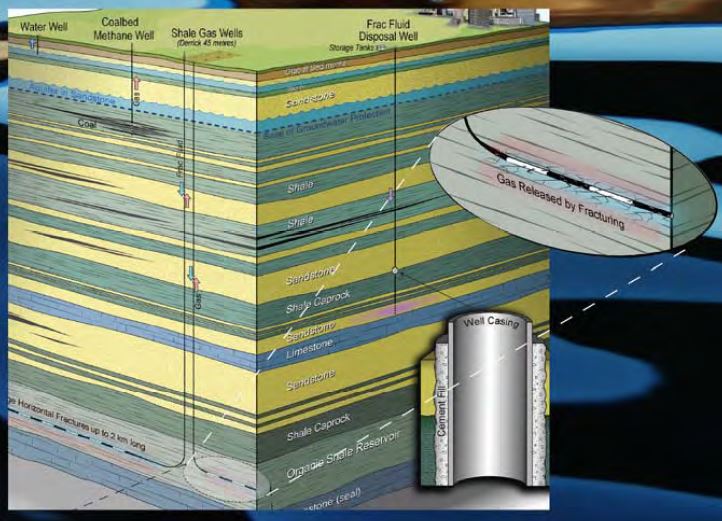

A nearby fracking operation had been pumping fluids deep underground to blast open a web of cracks to release oil. But 1,850 metres down the fracking fluids, propelled by immense pressure, shot through into the neighbouring well sending 75,000 litres of oily fracking fluids up the well and onto the snowy field in January 2012.

Alberta’s energy regulator later described it as “communication” between the two wells — one of more than 40 such “frack hits” reported in Alberta and British Columbia since 2009.

Regulators have introduced new rules to try to avoid such interactions, but as it gets more crowded underground observers say it is time for serious discussion about the way man-made holes and cracks in the ground are compromising the landscape and resources below.

The impact starts at the surface. Provincial rules require homes and buildings to be set back at least five metres from old wells. In Alberta, home to more than 450,000 wells, that means a lot of land off-limits as development encroaches on old oil and gas fields.

It’s even more complicated underground, where wells can not only “communicate” with each other, but create pathways that can potentially leak into groundwater aquifers and compromise resource development.

“If you have a leaking well and it doesn’t manifest at surface, you don’t know where it is leaking to,” says Theresa Watson, a Calgary-based engineer specializing in wellbores. She is also a former board member of the regulatory agency overseeing Alberta’s energy industry.

“It could be leaking into some other reservoir that you don’t want it to leak into for economic reasons,” says Watson, explaining how wells can “compromise” or “sterilize” areas against future resource development.

She points to the thousands of old or “legacy” wells dotting Alberta and Saskatchewan that may rule out use of steam-driven processes for extracting heavy oil and bitumen.

“Many old wells weren’t abandoned in any way that could handle thermal stress, and now those areas can’t be steamed and therefore the bitumen can’t be recovered,” says Watson.

Old wells can be repaired, but it won’t be cheap.

A report by Chris Diller, a Shell Canada engineer, has predicted it will take “billions of dollars to correct the abandonments” in Alberta alone. And he says “if these wells are not identified and abandoned properly, there is a high risk of negative impact to the environment, operator reputation, and the economics of field operations.”

Diller speaks from experience. Shell Canada wanted to store poisonous sour gas, which smells like rotten eggs, in an underground reservoir near the company’s Peace River operations in northern Alberta in 2010. But then Shell realized the reservoir had been compromised by an old well that was abandoned in 1989, after another company’s drilling gear got stuck 121 metres down the well. Diller says it took two months and cost Shell more than $5 million to repair the abandoned well.

An old well has also been implicated in the leak — one of the worst in Alberta — at the Primrose oilsands project where more than a million litres of a gooey bitumen-water mixture oozed out of the ground last year. (Alberta regulators say a cracked caprock on top of the bitumen layer also played a role in the leak).

And “frack hits,” which have occurred from Texas to northeast British Columbia, show that fracking operators do not always know when they are too close for comfort to other wells.

The “communications” between wells can undermine production and pose a serious safety and environmental hazard by sending fracking fluids into and up other wells. One “incident” in northeast B.C. in 2010 shot fracking fluids and sand into another well 670 metres away. Others have spilled thousands of litres of wastewater, fracking fluids, and oil and gas.

Alberta and B.C. energy regulators say the incidents are rare and have introduced rules and protocols that require fracking operations to stay 200 metres [What good is 200m if frac fluids and oil and or gas have shot out of energy wells much further away and companies are fracing directly into where the fresh water is, repeatedly, year after year?] from water wells, and to notify nearby well operators when fracking is taking place.

Abandoned and poorly cemented old wells are also a concern as researchers say they could potentially enable fracking fluids to migrate through cracks in and around the old wells’ casing and into underground aquifers. Decommissioned wells “constitute the seepage pathway of greatest risk for hydraulic fracking fluids,” says a report published in September by University of Waterloo researchers.

Co-author Richard Jackson, a groundwater expert with Geofirma Engineering Ltd. who teaches at Waterloo, is pushing regulators and industry to improve well seals and step up monitoring. [Experts have been pushing that for years, and are continue to be ignored by industry, regulators and elected officials] …

“There is no question that old wells are already a significant impediment to CO2 storage,” says Watson, who agrees it is time for “some serious thought” about the legacy the industry is leaving and how it may be “compromising future resource development.”

“If you’ve created a pathway, presumably that pathway of potential leakage could be there forever,” she says. [Emphasis added]

Thermal wells point to ‘worst case’ leaks from the deep by Margaret Munro, December 9, 2014, ocanada.com

The water burbles out of the earth carrying evidence of its underground voyage. It’s come from depths of up to five kilometres, bringing plenty of heat, gas and chemicals with it. Bright green and orange mats of micro-organisms grow on rocks where the water tumbles from the thermal springs in the mountains adjacent to areas of active hydraulic fracturing in northeastern B.C. and the southern Yukon.

The water is not from the fracking operations, but the springs show fluids can – and do – naturally make the trip to great depths.

They are like a “worst case scenario” showing that “communication” with the shale gas zone is possible, says Steve Grasby, a federal scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada, who has bushwhacked in to nine thermal springs where natural cracks and faults extend deep underground.

“We can see right next door to where shale gas development is going on that we do have circulation of surface (waters) down to five kilometres depth and back to surface again,” Grasby said in a recent presentation to the Geological Society of America’s annual meeting in Vancouver.

“Not only do we see transmission of water from the crustal levels but we also see transmission of thermogenic gas from the crust up to the surface in these spring systems,” he said.

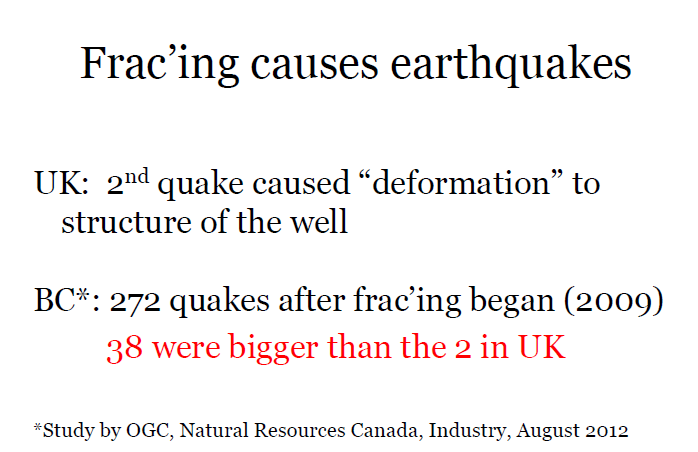

Thermogenic gas is the variety extracted by fracking. [Biogenic gas is also extracted by fracing, eg in Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. Many unconventional wells are “commingled” where gases from multiple depths are extracted in one well bore which prevents accurate isotopic fingerprinting of the gases thus preventing appropriate monitoring of groundwater] Mixtures of water and sand are injected under immense pressure to shatter rock and release the gas trapped two to three kilometres underground [And much more shallow]. The fracking process is so intense it can trigger small earthquakes, including 38 in northeast B.C., between 2009 and 2012.

Slide from Ernst presentations

Slide from Ernst presentations

Government regulators and industry say fracking fluids, which is water that can be laced with lead, arsenic, benzene and radioactive compounds, will stay put, locked in geological zones deep underground. But as wells proliferate in Western Canada where thousands of fracking wells have been drilled, so do concerns that fluids and gas will migrate through the growing collection of man-made holes, cracks and fractures beneath the ground.

Enough wastewater and industrial fluids to fill a lake 23 kilometres long, a kilometre deep, and a kilometre wide have been pumped into the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin underlying the Prairies since oil and gas production began. “And that’s probably an underestimate,” says Grant Ferguson at the University of Saskatchewan, who describes it as a “grand experiment.”

In British Columbia, billions of litres of water is not only injected into active fracking wells that can extend several kilometres underground, but the industry’s wastewater is pumped into old gas wells.

…

The nine thermal springs show that where there are cracks, water can travel.

Grasby says such natural springs are rare, with only nine located in the heavily fractured geological zone where the Rocky Mountains ram into the deep layers of shale containing the gas that energy companies are fracking in lower lying areas.

Grasby says rain and snowmelt percolates down, and then back up, to the springs through the natural cracks and faults.

The water returns carrying heat — the springs range from 30 C to 56 C — and chemicals leached out of rocks. It also carries gas from the shale layer, which is highly deformed and fractured where it runs up against the mountains.

One of the springs is at Liard, along the Alaska Highway, and the other eight are in more remote locations that Grasby says are easy to spot from the air.

“They tend to kill off big chunks of forest due to the high temperatures and mineral precipitation that is going on,” says Grasby.

At the springs calcium carbonate deposits cover the rocks and bright mats of micro-organisms that feast on the gas and chemicals from the deep. [Emphasis added]

Because of Leaking abandoned gas well: Lorain City Schools will move or tear down Admiral King gym by Carol Harper, November 19, 2014, The Morning Journal

A gymnasium must be moved or torn down at Admiral King Elementary School in Lorain so no part of the building remains over a gas well even after workers cap the well.

“We will possibly tear down the gym, reconfigure it, or move part of it over,” said Lorain City Schools Superintendent Thomas Tucker. … “We have to not have that gym over the gas well even if it’s capped,” Tucker said. “We’ve been told there are gas wells all over the city, but they can’t be under a building.”

With the rest of the school building sealed off from the gymnasium, staff and students may return to Admiral King at 720 Washington Ave. in Lorain, after workers cap the well and the site is cleared by safety officials, Tucker said.

Drilling around the pipe 600 feet down so it can be removed could take up to 20 days, Tucker said.

“We will be planning at some point moving back there,” Tucker said, “But we want to be sure all the ducks are in a row. I’ll feel a lot better once they start drilling tomorrow.

“What will we do with the gym? We’re talking to folks about what our options are,” Tucker said. “The good thing is the folks who designed all the buildings are familiar with this one. The buildings are new. They know where all the electric is, the plumbing, everything.” From half to one-third of the gymnasium sits in an area away from the well, Tucker said.

The gas well under Admiral King is a pipe that reaches 600 feet into the ground, with no tank, Tucker said. The well drew out natural-forming gas used to light homes years ago.

So far the gas leak has cost Lorain City Schools almost $200,000, Tucker estimated. The district has not received all of the bills for the Lorain Fire Department’s 24-hour-a-day monitoring, and workers tearing down a wall, opening a 20-foot-by-30-foot hole in the roof, and moving utility service out of the gymnasium, he said.

Jurisdiction issues and legal considerations further complicate the situation. Tucker said he cannot comment on insurance and deductibles. “Attorneys are handling it,” Tucker said. “We’re not sure it’s insurance. There are a whole lot of legal issues I’m not allowed to talk about right now.” The district built the school in cooperation with the Ohio School Facilities Commission.

The Ohio Department of Natural Resources oversees gas wells. “ODNR has been monitoring at the site since the first day,” Tucker said. “And ODNR is paying for the pipe removal and capping.” Contractors parked drilling equipment Nov. 19 in a warehouse owned by Lorain City Schools, Tucker said. They will set up a 60-foot-tall drilling rig beginning at 8 a.m. Nov. 20.

…

In a report Nov. 17 to the school board, Tucker said the work could proceed without going out for bid because of an emergency provision in Ohio law. “And we definitely consider what happened at Admiral King to be an emergency,” Tucker said. [Emphasis added]

Methane is leaking out all over the damn place, thanks to the oil and gas industry by John Light, December 10, 2014, Grist

Methane, the second most common greenhouse gas emitted by the U.S., is a scary, scary thing. Thanks to two new studies, we just found out a bit more about how, through drilling for oil and gas, it leaks into the air.

Compared with CO2, methane is frighteningly potent it’s 86 times more effective at trapping heat than CO2 over a 20-year time period. …

The first new study, put out by Princeton University and published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that millions of unused oil and gas wells across America could be leaking significant amounts of unreported methane. Researchers measured methane leaks from 19 abandoned wells in northwestern Pennsylvania. From a Princeton announcement:

- Only one of the wells was on the state’s list of abandoned wells. Some of the wells, which can look like a pipe emerging from the ground, are located in forests and others in people’s yards. [Researcher Mary] Kang said the lack of documentation made it hard to tell when the wells were originally drilled or whether any attempt had been made to plug them.

All of the 19 wells that the researchers looked at were leaking methane. All of them! But three of them were spitting out methane at thousands of times the levels that the others were. From an earlier study conducted by Stanford University, we know that there are around 3 million abandoned wells like the ones Princeton studied scattered across the U.S. That means abandoned wells like these that are just sitting out in the woods, not doing anything for anybody, could be making a notable contribution to climate change. Pennsylvania makes an attempt to plug those wells, but the Department of Environmental Protection, which is tasked with that work, is, predictably, understaffed. …

To sum up: Emissions from oil and gas wells both those that are currently operating and those that have been abandoned are a major issue that has been going largely unnoticed.

Unfortunately, America doesn’t have a system set up to monitor the wells and determine which are the major emitters. And, even if we did, there’s no standard policy on what to do with methane-leaking wells when we find them. …

Source:

Abandoned Wells Leak Powerful Greenhouse Gas, ClimateWire via Scientific American.

Methane still belches from USA’s old oil and gas wells, USA Today.

Abandoned oil and gas wells emit ‘significant’ methane by AFP, December 8, 2014

A significant amount of the potent greenhouse gas methane may be leaking into the atmosphere from abandoned oil and gas wells, according to a study in Pennsylvania out Monday. The study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences is based on direct measurements of methane outflow from and near 19 abandoned oil and gas wells in the northeastern US state.

Researchers at Princeton University in New Jersey and Stanford University in California took nearly 100 measurements over the course of seven months in 2013 and 2014, and found that all the wells they studied emitted methane, whether they were in forests, wetland, grassland, or river areas.

Three of the 19 wells were so-called “high emitters,” sending out methane at three time the median, or midpoint, rate. The study said that if the 19 wells studied are typical of the overall situation in the northeastern state of Pennsylvania, the abandoned wells may account for four to seven percent of methane emissions in the state. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to:

2013 06: FrackingCanada The Science is Deafening Industry’s Gas Migration

2014 07 17: There are proven cases of frac’ing contamination

Complete Slides. Teresa Watson was on the Board of the Alberta Energy Regulator from 2009 – 2013

Complete Slides. Teresa Watson was on the Board of the Alberta Energy Regulator from 2009 – 2013

Slide from Ernst presentations