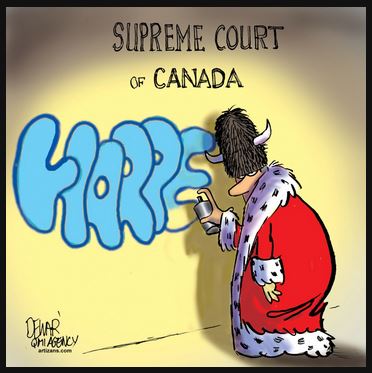

Harper accused of trying to ‘intimidate’ Supreme Court justices by Jeff Lacroix-Wilson with files from The Canadian Press, May 5, 2014

The Harper government faced accusations Monday of trying to intimidate Canada’s top judges, as the question of whether a Supreme Court chief justice can talk to the government about judicial appointments spilled into the House of Commons. “Does the attorney general consider that it is part of his job to ensure that there are never any attempts to intimidate the courts in our country?” NDP leader Tom Mulcair asked Justice Minister Peter MacKay.

“The attorney general’s job is to defend the integrity of the court system in our country, not to help the prime minister attack the chief justice. Is our attorney general telling us that he will be the henchman of the prime minister in this unwarranted, unprecedented attack on the Supreme Court and its chief justice?”

A chorus of critics and legal experts has criticized Stephen Harper over the rhetorical war that broke out last week between the prime minister and the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Beverley McLachlin.

The Canadian Bar Association wants Harper to state publicly that McLachlin did nothing wrong in trying to raise an issue surrounding the nomination of a justice to the top court.

But Harper’s office implied that McLachlin, Canada’s longest-serving chief justice, had inappropriately questioned the eligibility for the court of a Quebec nominee, Marc Nadon.

Monday, MacKay escalated the feud, implying that the Supreme Court itself went beyond the strict wording of the law when it then went on to nix Nadon’s appointment. In March, the court found Nadon ineligible to sit as one of three Quebec judges on the Supreme Court because he came from the Federal Court of Appeal. The Supreme Court Act specifies that Quebec judges must come from either the province’s Court of Appeal or Superior Court, or have at least 10 years’ standing at the Quebec bar. However, MacKay said that until the Supreme Court ruled Nadon ineligible, there was nothing in the Act to prohibit the appointment of a Federal Court judge to one of the Quebec slots on the top bench.

None of this impressed Mulcair. He said the government’s moves were “a direct attempt to intimidate the Supreme Court.”

Last week, Harper accused McLachlin of inappropriately trying to make an “inadvisable and inappropriate” phone call to warn him that there might be an eligibility problem with Nadon’s appointment.

Fred Headon, president of the Canadian Bar Association, said the government’s comments could undermine the nation’s trust in its top court.

But PMO spokesperson Jason MacDonald said MacKay and Harper “stand by their comments.”

Former Justice Minister Irwin Cotler, now an opposition Liberal MP, argued that contacting the government about appointments was part of Mclachlin’s job. “Consultations between a chief justice and minister of justice are a normal part of the appointments process,” Cotler said. “The chief justice is a perfectly appropriate person to provide the minister with input … particularly on the administration of justice,” said Cotler. He said that at the time McLachlin offered her advice, “Nadon had not even been nominated … let alone appointed.”

Cutler said, “any time an officer of Parliament renders an opinion that is adverse to the government, it responds by attacking their credibility.”

McLachlin’s office said in a statement Friday that the chief justice did not try to interfere in Nadon’s appointment. The statement insisted there is “nothing inappropriate” in raising issues with the government about the eligibility of a nominee.

The Harper government has been at odds with several of the top court’s decisions. [Emphasis added]

L’etat, c’est Steve by Michael Harris, May 4, 2014, ipolitics.ca

As Prime Minister Stephen Harper attacks the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in broad daylight, there is a question Canadians need to answer fairly soon. What’s it going to be: a modern democracy or a Steve’s banana republic of the north?

Steve likes people docile. He appears to have tamed a lot of the realm. He kicks, the subjects cringe. He kicks some more, they slip into the woods of indifference. They are so disconnected that they no longer hear the screams of the other kickees: Linda Keen, Bill Casey, Kevin Page, Marc Mayrand, even Sheila Fraser — and now, and now, Beverley McLachlin, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada.

The train wreck of the Harper government continues to roll down the mountainside, crushing body after body, yet no one utters the right word. Allow me. Canada is a dictatorship in the making.

Did you ever know a person who just kept taking more and more from a relationship until you had to draw a line? A person for whom there are no rules, just a bottomless appetite to have it all their own way?

…

Look at all the portfolios and offices now held by Steve. The proclamation for the upcoming National Day of Honour, commemorating the end of a war in Afghanistan that should never have begun, was announced by Governor-General Harper. Governor-General Harper will also receive the last military flag from Kandahar, while David Johnson watches. Commander-in-Chief Harper will have the spotlight at the National Day of Honour ceremonies; the real generals who commanded troops in Afghanistan were not invited because they do not like blue Kool-Aid.

Speaker of the House of Commons Harper ruled that it was perfectly okay to keep information from the opposition because they were not real MPs anyway.

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Harper has declared that the appointment of Marc Nadon to the Supreme Court was completely in order — despite his 6-1 rejection by that other interventionist-court.

Intergovernmental Affairs Minister Harper declared that Quebec was a “nation”, though the matter was never discussed in cabinet, nor for that matter, passed on to the pretend intergovernmental affairs minister back then, Michael Chong … and on and on.

…

Based on his actions, the PM is a misanthropic powermonger who misread 1984; the hero was Winston Smith, Steve, not Big Brother. This PM has so many fundamentally warped ideas about Canada that it won’t be long before he appears in public in a uniform.

Harper’s poisonous toads began whispering in the corridors of the Commons that McLachlin had crossed a line. In doing their master’s bidding, they implied that the Chief Justice had somehow been against the Nadon appointment and had moiled against it.

Sorry … he already has, though it violated military protocol. How could I forget Steve in that flight jacket with real pilot wings on it, flying over the flooding in Alberta? I suppose he forgot that if there’s one thing real servicemen hate, it’s a civilian wearing as a prop a uniform which he is not entitled to wear.

Steve has never shown much insight into Canada, though he was cunning enough in the beginning to know that the country was asleep at the switch. He thinks that, under our system, Canadians elect governments — when they actually elect parliaments. Under Steve’s view, if you are not a Conservative MP, you are nothing at all. Which is why he wouldn’t share public information with the opposition, a misinterpretation of the rules that earned him a contempt of Parliament ruling.

…

This week, Steve’s calm Kabuki mask slipped off. Underneath, for all to see, was what former mentor Tom Flanagan has been talking about on his latest book tour — the suspicious, vindictive, secretive man who routinely plays politics right up to, and occasionally over, the edge of the rules. I cite those words carefully. In one of the scuzzier low blows in politics I’ve seen in a long time, Steve unleashed his goons on McLachlin, someone he knows has very little ability to defend herself publicly.

Harper’s poisonous toads began whispering in the corridors of the Commons that McLachlin had crossed a line. In doing their master’s bidding, they implied that the Chief Justice had somehow been against the Nadon appointment and had moiled against it; that her attempt to communicate some constitutional reality to Harper before he made an ass of himself with his SC choice was in some way “political.” It was actually normal, not to mention merciful. Steve needs help. Given his batting average in the Supreme Court, he needs a lot of help.

Instead, Steve didn’t merely fail to put a stop to the drive-by smear of the chief justice, he lathered on a few greasy streaks of his own. He said he did nothing wrong in the unconstitutional appointment of Marc Nadon. And you know what that means. It means that the chief justice was wrong. You know the fundraising letters have already gone out to the Conservative base: the Harper government’s plans were stymied by an interventionist judge. I wonder if that also means Steve doesn’t feel bound by the ruling. I suppose we’ll know if Marc Nadon becomes the next Chief Justice. That’s payback, Steve-style.

So what is the demonization of McLachlin all about? It’s about five glaring, embarrassing, damaging, unnecessary, and perfectly justified defeats in the highest court in the land. Harper is not a lawyer and really had no idea what he was talking about….

So now Steve has shown contempt for the House of Commons, the Senate and the Supreme Court. [Emphasis added]

[Refer also to:

A self-made-up man by Jessica Ernst, October 6, 2008, The Edmonton Journal

Heavily made-up Stephen Harper cuddles babies to press his family-man election spin. Would a real family man travel with a make up artist and keep the costs of this vanity secret? Why would Harper, with all his disdain and budget cuts for artists, not learn to put on his own makeup? Millions of Canadian women do. ]

Harper government not backing down from spat with Supreme Court chief justice by The Canadian Press, May 5, 2014, The Lethbridge Herald

The Harper government is not backing down from its unprecedented public spat with the chief justice of the country’s highest court. Indeed, Justice Minister Peter MacKay has escalated the feud, implying that the Supreme Court went beyond the strict wording of the law to nix the appointment of Marc Nadon to the top court’s bench.

It was the Nadon decision that triggered a tit-for-tat war of words last week between Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin. Last March, the court found Nadon ineligible to sit as one of three Quebec judges on the Supreme Court because he came from the Federal Court of Appeal. The Supreme Court Act specifies that Quebec judges must come from either the province’s Court of Appeal or Superior Court, or have at least 10 years standing at the Quebec bar.

However, MacKay says that until the Supreme Court ruled Nadon ineligible, there was nothing in the act to prohibit the appointment of a Federal Court judge to one of the Quebec slots on the top bench. [Emphasis added]

Stephen Harper’s reckless smear of Canada’s top judge by Andrew Coyne, May 5, 2014, Edmonton Journal

Watching the Harper government stumble from one needless controversy to another — picking fights, settling scores, demeaning institutions and individuals alike in the pursuit of no discernible principle or even political gain — one has had the distinct impression of a government, and a prime minister, spinning out of control.

But with the prime minister’s astonishing personal attack last week on the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Beverley McLachlin, the meltdown has reached Lindsay Lohanesque proportions. Nothing in the long catalogue of Stephen Harper’s bad-tempered outbursts has seemed quite so extravagantly reckless, if only because it was so calculated.

It is one thing to savage a political opponent or beat up on a distinguished civil servant. But to accuse the nation’s highest judge of professional misconduct — for that is what was insinuated, if not quite alleged, an ethical breach serious enough to warrant her resignation — is so ill-considered, so destructive of both the court’s position and his own, that it leaves one wondering whether he is temperamentally suited to the job.

Those anonymous Conservative MPs who have seized on the controversy to grouse, yet again, that judges are “making law” in defiance of the wishes of Parliament are likewise within their rights, though they seem to misunderstand basic principles of constitutional government — as in the suggestion from some bright light to the National Post’s John Ivison that the appropriate response to the Nadon decision was to invoke the notwithstanding clause. For a system of written law to work, there must be an independent arbiter to interpret it; if laws meant whatever the prime minister of the day claimed they did, we would effectively be living under rule by decree.

… What’s absolutely out of bounds is to start casting aspersions on the personal integrity of individual judges — let alone the chief justice. That wasn’t the work of some bumptious Tory backbencher. It came straight out of the Prime Minister’s Office.

The whole situation might have been avoided, of course, had the chief justice never called the justice minister, but confined her attempts to “flag” the possible legal issues raised by the Nadon appointment to the panel of MPs charged with vetting candidates for the court. That is a long, long way, however, from any suggestion she did anything improper. Yet that is the impression the prime minister has laboured to plant in the public mind.

…

The statement neglected to mention the date of the call, leaving observers to wonder whether she might have called after Nadon’s appointment had been challenged in Federal Court, or even after it had been referred to the Supreme Court. That would indeed be highly improper. In fact, as a statement from the chief justice’s office later revealed, the call to the justice minister (she never called the prime minister) was made July 31 of last year. That’s two months before Nadon was appointed, and nearly three months before the government referred the issue to the court.

A parade of legal authorities have said she did nothing wrong: the Canadian Bar Association, which has called upon the prime minister to clarify his statement accordingly; scholars such as the University of Ottawa’s Adam Dodek (“There is nothing unusual about contacts between the chief justice and the minister of justice and the prime minister”); the former Supreme Court judge Jack Major (“innocuous”).

But never mind. Suppose the prime minister were as troubled by her actions as he now feels compelled to advertise. Why did he wait nine months to raise it? Why did he not, at a minimum, insist she recuse herself from the reference? Why does he not, even now, bring proceedings against her, or demand that she resign? We are left with two possibilities. Either the prime minister knew the chief justice had committed a serious ethical breach, and did nothing about it. Or he knew, as he knows now, that she did no such thing, but is content to smear her as if she had.

As I say, we’ve never seen anything quite like this, not even from this prime minister. Which raises the question: At what point do Conservatives of goodwill become concerned about the long-term damage being done to their party’s reputation under its present leadership? Differences over policy come and go, but this kind of behaviour, left unchallenged, will lead many people to conclude that the institutions of government cannot be safely entrusted to them. [Emphasis added]

Chief Justice hits back at Prime Minister over claim of improper call by Sean Fine, May 2, 2014, The Globe and Mail

An extraordinary showdown between Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin has intensified, with the jurist denying wrongdoing, and disputing Mr. Harper’s recollection of the facts. The court issued a statement a little after noon on Friday, defending itself against the top-level attack on its integrity: “At no time was there any communication between Chief Justice McLachlin and the government regarding any case before the courts.”

The Prime Minister’s Office had levelled a serious, but indirectly phrased, accusation the evening before – that Chief Justice McLachlin tried to involve Mr. Harper in an inappropriate discussion about a case that was either before the court or that could come before the court. If true, the longest-serving chief justice in the court’s history might have to resign, or face the unheard-of prospect that the House of Commons and Senate would unite to force her off the bench.

“The PM is imputing inappropriate interference to the Chief Justice and it’s very personal, it’s superpersonal,” McGill University law professor Robert Leckey said.

Until now, the Conservative government and the country’s highest court had wrestled each other in the traditional ways – in court filings and hearings. But after five rulings in as many weeks in which the court rejected key elements of the government’s agenda, something changed. Those rulings, in sum, were a rejection of Mr. Harper’s long-held views on Parliament’s supremacy.

And then, on Thursday evening, Mr. Harper registered a serious allegation against the Chief Justice in the court of public opinion. And the conflict between the court and the government moved on to uncharted ground. The Chief Justice, the Prime Minister’s Office said in a news release, had tried to involve him in an inappropriate conversation about a case. “Neither the Prime Minister nor the Minister of Justice would ever call a sitting judge on a matter that is or may be before their court,” the release said. “The Chief Justice initiated the call to the Minister of Justice. After the Minister received her call he advised the Prime Minister that given the subject she wished to raise, taking a phone call from the Chief Justice would be inadvisable and inappropriate.” The case in question was the Supreme Court appointment of Justice Marc Nadon, a member of the Federal Court of Appeal. … (The court ruled Justice Nadon ineligible in March, the first time in a common-law country an appointed Supreme Court judge had been rejected by a court as ineligible, according to political scientist Carl Baar.)

The PMO’s statement follows a recent pattern of blaming the judiciary for the government’s inability to move forward on Senate reform, a key concern for many Conservative voters. Last week, Mr. Harper called the court’s ruling on the matter a “decision for the status quo,” which he said almost no Canadian could support.

Responding to the PMO’s statement, the court said that Chief Justice McLachlin’s contact with the Justice Minister occurred on July 31 – two months before Justice Nadon was chosen for the court. The court said she was simply flagging the potential issue around the eligibility of a Federal Court judge. It also said that her office had made preliminary inquiries about contacting the Prime Minister, but that the Chief Justice had decided against it – a much different version from the PMO’s statement.

Legal observers, including the Canadian Bar Association, representing 37,000 lawyers and judges, said that they found no fault with the Chief Justice, and that it is common practice in Canada for chief justices to consult with governments during the appointment process. John Major, a former Supreme Court judge, called her contacts with the government “innocuous.” “I don’t view it as calling about a case. It’s about the operation of the court,” he said. Adam Dodek, a University of Ottawa law professor, said that if the government felt the Chief Justice had acted inappropriately, the Justice Minister had an obligation to publicly challenge her ability to hear the case before it began. Fred Headon, president of the Canadian Bar Association, said he hopes the PMO’s statement was based on a misunderstanding. “It is troubling because it threatens to discredit the chief and the institution of the court and by extension the judiciary throughout Canada.” [Emphasis added]

Attempt to smear Chief Justice an affront to our constitutional system by Errol Mendes, May 2, 2014, The Globe and Mail

Errol Mendes is a professor of constitutional and international law at the University of Ottawa and is the founding editor-in-chief of the National Journal of Constitutional Law.

A fundamental principle of democracy is that elected governments understand and appreciate the workings of checks and balances against their range of powers. In the Canadian constitutional system, even if a government has a majority in the House of Commons, a prime minister will understand that his political goals will sometimes be challenged by a range of actors in society from citizens to the courts.

Unfortunately, since the Conservative Party under the leadership of Prime Minister Stephen Harper was elected – first to the position of a minority government in 2006 and presently as a majority government – those that have offered reasonable and legitimate advice and challenges to the political and legal goals of the Harper government have faced unprecedented smears from the highest ranks of the party and the government.

The growing range of individuals that have had to endure such smears have included: academics (myself included); environmental groups labelled as extremists and radicals funded by foreign entities; public servants just doing their job, such as Linda Keen, the former head of the nuclear safety watchdog, Peter Tinsley, the head of the Military Police Complaints Commission and Richard Colvin, the foreign service officer who testified on the treatment of Afghan detainees; Chief Electorial Officer Marc Mayrand for alleged bias; and, astonishly, former auditor general Sheila Fraser, who has faced innuendos of conflicts of interest.

However, even this level of extreme anti-democratic behaviour has been surpassed with the current attempted smear against the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, Beverly McLachlin. The Prime Minister’s Office has suggested that Ms. McLachlin inappropriately tried to call Mr. Harper’s office about the appropriateness of selecting Marc Nadon for the Quebec vacancy on the Court. PMO spokesman Jason MacDonald asserted that the Prime Minister rebuffed the call of the Chief Justice on the advice of his justice minister. The spokesman asserted that the Chief Justice initiated the call first to the Minister of Justice, Peter MacKay, and that he advised Mr. Harper not to take her call – which he concurred with. The implication of these statements is that the Chief Justice acted inappropriately, as according to the statement of Mr. MacDonald: “Neither the Prime Minister nor the Minister of Justice would ever call a sitting judge on a matter that is or may be before their court.”

In contrast to this attempt to impute the integrity of one of the most distinguished jurists in Canadian history with a global reputation for effectively presiding over some of the most challenging legal and constitutional issues facing the country, the actions of the Chief Justice could actually have been in the best interests of the country and the Court.

It was perfectly legitimate for the Chief Justice to advise Mr. MacKay on the consequences of appointing a judge from the Federal Court for a Quebec seat. Indeed, what the attempted smear does not reveal is that the Chief Justice was consulted by the parliamentary committee screening the short list of candidates and she provided her views on the needs of the Court. Given her position, it would be totally appropriate to go further and speak directly to the Minister of Justice. Given the institutional impact on the Court, it would be negligent for the Chief Justice not to do so. According to the executive legal officer of the Court, Owen Rees, at no time did the Chief Justice express any views on the merits of the appointment of Mr. Nadon.

Likewise, it would also be negligent of the Prime Minister either directly or through the advice of his Justice Minister not to seek the views of the Chief Justice for appointments to the Court, as other justice ministers and possibly prime ministers in the past have done.

To then turn these consultations into an innuendo of inappropriate lobbying by the Chief Justice is to endanger one of the most important aspects of Canadian constitutional democracy, the relationship of respect and credibility between the judicial and executive arms of our constitutional democracy. This should be the most cherished of constitutional principles, even if the highest court has ruled against the government on some of it most cherished political goals. Democracy demands it. [Emphasis added]

Duelling statements over failed Nadon appointment reveal PMO fight with top court by Bruce Cheadle, May 1, 2004, The Lethbridge Herald

The Prime Minister’s Office says Stephen Harper refused to take a call from the country’s chief justice about who should be allowed to sit on the Supreme Court of Canada.

The Prime Minister’s Office exposed an unprecedented public spat with the chief justice of the Supreme Court on Thursday, issuing a statement suggesting Stephen Harper refused to accept a phone call from Beverley McLachlin about a judicial appointment. The extraordinary statement came on the heels of a media report that said Conservative government members have become incensed with the top court after a series of stinging constitutional rebukes.

Among those government setbacks was a court ruling that Justice Marc Nadon, Harper’s most recent pick for the top bench, was not qualified under the Supreme Court Act. The nine-member court has been short one justice for almost a year as a result of the bungled appointment.

Harper’s chief spokesman issued a statement late Thursday saying that McLachlin “initiated” a call to Peter MacKay, who was justice minister at the time, to discuss the Nadon appointment at some point during the selection process. “After the minister received her call he advised the prime minister that, given the subject she wished to raise, taking a phone call from the chief justice would be inadvisable and inappropriate,” Jason MacDonald said in the statement. “The prime minister agreed and did not take her call.”

Earlier Thursday, the Supreme Court’s executive counsel issued his own extraordinary statement, saying McLachlin’s advice had been sought by the committee of MPs vetting possible Supreme Court nominees. “The chief justice did not lobby the government against the appointment of Justice Nadon,” said the statement from Owen Rees, the court’s executive counsel. “She was consulted by the parliamentary committee regarding the government’s shortlist of candidates and provided her views on the needs of the court.”

McLachlin’s office pointed out to both the justice minister and to the prime minister’s chief of staff that appointing a Quebec justice from the Federal Court of Appeal could pose a problem under the rules – an issue Rees said was “well-known within judicial and legal circles.”

Rees wrote that McLachlin “did not express any views on the merits of the issue.” It is also unclear whether the chief justice ever asked to speak directly with the prime minister on the matter.

What is clear is that as early as last August, the Harper government knew the appointment of Nadon was legally problematic.

The Supreme Court Act clearly lists the courts where the three Quebec representatives on the bench can be appointed from. Neither the Federal Court nor the Federal Court of Appeal are among them.

…

However after Nadon was sworn in last October, Toronto constitutional lawyer Rocco Galati challenged the appointment. In March, the top court issued a 6-1 ruling that declared Nadon ineligible. Although Harper accepted the court ruling at the time, the statement from his office Thursday continued to question that judgment.

As MacDonald wrote in the PMO statement, “None of these (government-commissioned) legal experts saw any merit in the position eventually taken by the court and their views were similar to the dissenting opinion of Justice Moldaver,” the lone dissenter in the 6-1 Supreme Court judgment.

NDP Leader Tom Mulcair described the dissent as typical of Harper’s Conservative government. “It’s too bad for the Canadian public because, at the end of the day, it can rely only on its democratic institutions,” Mulcair said. “(Harper) always sees a conspiracy as soon as someone says no to him.” [Emphasis added]

Harper refused call from Supreme Court chief justice on Nadon appointment by The Canadian Press, May 1, 2014, Lethbridge Herald

The Prime Minister’s Office says Stephen Harper refused to take a call from the country’s chief justice about who should be allowed to sit on the Supreme Court of Canada. The call was placed in the midst of controversy surrounding the nomination of Marc Nadon to the top court.

The PMO says Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin put in a call to then-justice minister Peter MacKay to discuss the appointment, which the high court has since disallowed. The justice minister then called Harper to give him a heads-up, warning him not to discuss the matter with her because the call would be “inadvisable and inappropriate.” The PMO says the prime minister agreed, and did not take the call. The Nadon appointment was controversial even before it was made official. … The appointment was challenged in court and Nadon was deemed ineligible for the appointment. [Emphasis added]

Harper’s judicial losing streak reveals the limits of government action by Sean Fine, April 27, 2014, The Globe and Mail

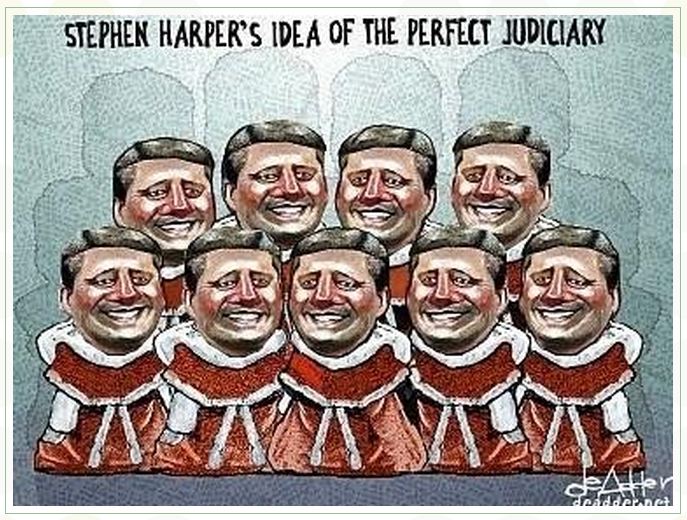

Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s guiding philosophy of governing without worrying about activist judges has run smack into the Supreme Court of Canada. Five overwhelming losses in little more than a month, all of them in areas dear to the Conservative government’s heart, leave Mr. Harper with a tough choice: Make a political issue of being opposed by unelected judges or modify his agenda (and perhaps his governing style) so it will pass legal muster. In all five cases, including Senate reform on Friday, three tough-on-crime laws and even Mr. Harper’s choice for a Supreme Court judge, only one supportive voice was raised on the court, and just once. And this from a court whose eight members include five appointed by Mr. Harper.

It has been a rapid-fire education in the limits of government action – or a comeuppance – with few parallels in Canadian history, some legal observers say. Mr. Harper’s losing streak “highlights a judicial-legislative clash in ways that have not been highlighted in the recent past, and perhaps ever,” Wayne MacKay, a constitutional specialist at Dalhousie University’s law school in Halifax, said in an interview.

…

“The Charter of Rights has brought about a mindset, a culture or a way of thinking among legislators that in practical terms limits the democratic institutions to act proactively or indeed to react to serious situations,” Vic Toews told a pro-life conference in Winnipeg. That speech points to Mr. Harper’s more aggressive mindset. His own public criticisms of judicial activism convey the view that the Supreme Court has wrongly asserted its supremacy over Parliament, and should be challenged on it.

…

Others, such as Prof. MacKay, cast Mr. Harper’s views in a negative light. “My personal, obviously biased view [as a law professor] is he doesn’t adequately respect and value the role of the courts in a checks and balances system. It’s almost a kind of arrogance. ‘I know what is best; I’m acting on behalf of the people of Canada and therefore, why should unelected, appointed bodies be able to block my vision of what is best for Canada?’ ” Either way, though, what unites all five cases in the Harper losing streak is that “there are certain limits that you cannot cross, because we have a Constitution within which you must operate,” Prof. MacKay said.

The court that has handed such stinging defeats to Mr. Harper is hardly a bunch of activists. Mr. Harper has mostly appointed conservative jurists whose tendency is to defer to government, such as Justices Marshall Rothstein, Michael Moldaver and Richard Wagner. “I don’t think any of these cases indicate an activist judiciary,” said Joel Bakan, a professor at the University of British Columbia’s law school.

“The decisions are not at all controversial when you look at them from a legal perspective. What they indicate is a government that has overreached in its power. The Harper government has gone after some very ancient and rooted common-law protections.” In one case, the government imposed retroactive limits on parole. In another, judicial discretion over sentencing was constrained. In a third, habeas corpus, the right of prisoners to go before a judge and protest against the conditions of their confinement, was restricted. The question for Mr. Harper is where to go next, as his policy agenda runs aground. He could become more conciliatory, as in last week’s climb down on the proposed Fair Elections Act, which might ultimately have been challenged at the Supreme Court. Or he could make the Supreme Court’s rejection of his policies a political issue.

…

Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin speaks of a “dialogue” between Parliament and the judiciary, but the five cases appear to leave little room for a government reply. On Senate reform, for instance, Ottawa has no appetite for opening constitutional talks with the provinces. (Perhaps most Canadians share that reluctance.) On sentencing, where the Supreme Court urged the federal government to be open about what it is trying to do, it may be hard to address the principle of proportionality without receiving another rebuke from the judiciary. The cases may prove more dead end than dialogue. [Emphasis added]